Challenges to British Imperial Hegemony in the Mediterranean 1919-1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fascist Italy's Aerial Defenses in the Second World War

Fascist Italy's Aerial Defenses in the Second World War CLAUDIA BALDOLI ABSTRACT This article focuses on Fascist Italy's active air defenses during the Second World War. It analyzes a number of crucial factors: mass production of anti- aircraft weapons and fighters; detection of enemy aircraft by deploying radar; coordination between the Air Ministry and the other ministries involved, as well as between the Air Force and the other armed services. The relationship between the government and industrialists, as well as that between the regime and its German ally, are also crucial elements of the story. The article argues that the history of Italian air defenses reflected many of the failures of the Fascist regime itself. Mussolini's strategy forced Italy to assume military responsibilities and economic commitments which it could not hope to meet. Moreover, industrial self-interest and inter-service rivalry combined to inhibit even more the efforts of the regime to protect its population, maintain adequate armaments output, and compete in technical terms with the Allies. KEYWORDS air defenses; Air Ministry; anti-aircraft weapons; bombing; Fascist Italy; Germany; radar; Second World War ____________________________ Introduction The political and ideological role of Italian air power worked as a metaphor for the regime as a whole, as recent historiography has shown. The champions of aviation, including fighter pilots who pursued and shot down enemy planes, represented the anthropological revolution at the heart of the totalitarian experiment.1 As the Fascist regime had practiced terrorist bombing on the civilian populations of Ethiopian and Spanish towns and villages before the Second World War, the Italian political and military leadership, press, and industrialists were all aware of the potential role of air 1. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

The Gordian Knot: American and British Policy Concerning the Cyprus Issue: 1952-1974

THE GORDIAN KNOT: AMERICAN AND BRITISH POLICY CONCERNING THE CYPRUS ISSUE: 1952-1974 Michael M. Carver A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2006 Committee: Dr. Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor Dr. Gary R. Hess ii ABSTRACT Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor This study examines the role of both the United States and Great Britain during a series of crises that plagued Cyprus from the mid 1950s until the 1974 invasion by Turkey that led to the takeover of approximately one-third of the island and its partition. Initially an ancient Greek colony, Cyprus was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century, which allowed the native peoples to take part in the island’s governance. But the idea of Cyprus’ reunification with the Greek mainland, known as enosis, remained a significant tenet to most Greek-Cypriots. The movement to make enosis a reality gained strength following the island’s occupation in 1878 by Great Britain. Cyprus was integrated into the British imperialist agenda until the end of the Second World War when American and Soviet hegemony supplanted European colonialism. Beginning in 1955, Cyprus became a battleground between British officials and terrorists of the pro-enosis EOKA group until 1959 when the independence of Cyprus was negotiated between Britain and the governments of Greece and Turkey. The United States remained largely absent during this period, but during the 1960s and 1970s came to play an increasingly assertive role whenever intercommunal fighting between the Greek and Turkish-Cypriot populations threatened to spill over into Greece and Turkey, and endanger the southeastern flank of NATO. -

The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870

The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Dzanic, Dzavid. 2016. The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840734 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 A dissertation presented by Dzavid Dzanic to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2016 © 2016 - Dzavid Dzanic All rights reserved. Advisor: David Armitage Author: Dzavid Dzanic The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 Abstract This dissertation examines the religious, diplomatic, legal, and intellectual history of French imperialism in Italy, Egypt, and Algeria between the 1789 French Revolution and the beginning of the French Third Republic in 1870. In examining the wider logic of French imperial expansion around the Mediterranean, this dissertation bridges the Revolutionary, Napoleonic, Restoration (1815-30), July Monarchy (1830-48), Second Republic (1848-52), and Second Empire (1852-70) periods. Moreover, this study represents the first comprehensive study of interactions between imperial officers and local actors around the Mediterranean. -

Press Release Bytro Labs Cooperates with Sponsorpay Freiburg, 09/09/09

Bytro Labs UG (haftungsbeschränkt) Stefan-Meier-Str. 8 79104 Freiburg +49 761 203 5462 [email protected] Press release Bytro Labs cooperates with SponsorPay Freiburg, 09/09/09: Users of the strategy game “Supremacy 1914” can now earn in-game currency using the SponsorPay platform. The SponsorPay platform serves as a monetisation tool for social games & apps, online games and virtual worlds, as well as for other publishers who have integrated virtual currency or premium features. Instead of paying with their own money, players can complete one of the numerous offers from SponsorPay’s advertising partners and get Supremacy 1914 Goldmarks for free in return. “SponsorPay convinced us with their strict policy for selecting advertising partners. We believe, that with the integration of SponsorPay we can achieve a sustainable increase of revenue.” comments Felix Faber, Co-Founder and CEO of Bytro Labs on the cooperation. About SponsorPay SponsorPay GmbH, which is seated in Berlin Mitte, was founded by Team Europe Ventures, Jan Beckers and Janis Zech and is currently employing 25 people. SponsorPay serves Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the U.K., France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, Russia, the US, Canada and Turkey with native country managers and a localized product. Through their partners SponsorPay is able to reach more than 10 million users throughout Europe. About Supremacy 1914: Supremacy 1914 – Become the leader of a nation and conquer Europe In Supremacy 1914, the player becomes head of a mighty nation in precarious Europe after the turn of the century. He faces the challenge to become the undisputed sovereign leader of the whole continent using smart diplomacy or simply the brute force of his glorious armies. -

Directorate for Quality and Standards in Education

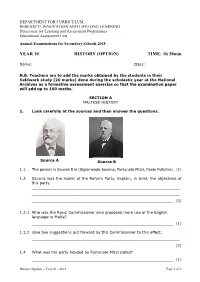

DEPARTMENT FOR CURRICULUM, RESEARCH, INNOVATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING Directorate for Learning and Assessment Programmes Educational Assessment Unit Annual Examinations for Secondary Schools 2018 YEAR 10 HISTORY (OPTION) TIME: 1h 30min Name: _____________________________________ Class: _______________ N.B. Teachers are to add the marks obtained by the students in their fieldwork study (20 marks) done during the scholastic year at the National Archives as a formative assessment exercise so that the examination paper will add up to 100 marks. SECTION A MALTESE HISTORY 1. Look carefully at the sources and then answer the questions. Source A Source B 1.1 The person in Source B is (Sigismondo Savona, Fortunato Mizzi, Paolo Pullicino). (1) 1.2 Savona was the leader of the Reform Party. Explain, in brief, the objectives of this party. _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (3) 1.3.1 Who was the Royal Commissioner who proposed more use of the English language in Malta? ____________________________________________________________ (1) 1.3.2 Give two suggestions put forward by this Commissioner to this effect. _______________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ (2) 1.4 What was the party headed by Fortunato Mizzi called? ____________________________________________________________ (1) History (Option) – Year 10 – 2018 Page 1 of -

Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta

Vol:1 No.1 2003 96-118 www.educ.um.edu.mt/jmer Politics, Religion and Education in Nineteenth Century Malta George Cassar [email protected] George Cassar holds the post of lecturer with the University of Malta. He is Area Co- ordinator for the Humanities at the Junior College where he is also Subject Co-ordinator in- charge of the Department of Sociology. He holds degrees from the University of Malta, obtaining his Ph.D. with a thesis entitled Prelude to the Emergence of an Organised Teaching Corps. Dr. Cassar is author of a number of articles and chapters, including ‘A glimpse at private education in Malta 1800-1919’ (Melita Historica, The Malta Historical Society, 2000), ‘Glimpses from a people’s heritage’ (Annual Report and Financial Statement 2000, First International Merchant Bank Ltd., 2001) and ‘A village school in Malta: Mosta Primary School 1840-1940’ (Yesterday’s Schools: Readings in Maltese Educational History, PEG, 2001). Cassar also published a number of books, namely, Il-Mużew Marittimu Il-Birgu - Żjara edukattiva għall-iskejjel (co-author, 1997); Għaxar Fuljetti Simulati għall-użu fit- tagħlim ta’ l-Istorja (1999); Aspetti mill-Istorja ta’ Malta fi Żmien l-ingliżi: Ktieb ta’ Riżorsi (2000) (all Għaqda ta’ l-Għalliema ta’ l-Istorja publications); Ġrajja ta’ Skola: L-Iskola Primarja tal-Mosta fis-Sekli Dsatax u Għoxrin (1999) and Kun Af il-Mosta Aħjar: Ġabra ta’ Tagħlim u Taħriġ (2000) (both Mosta Local Council publications). He is also researcher and compiler of the website of the Mosta Local Council launched in 2001. Cassar is editor of the journal Sacra Militia published by the Sacra Militia Foundation and member on The Victoria Lines Action Committee in charge of the educational aspects. -

Stillfront Announces Its Intention to Raise Equity Capital by Way of a Private Placement and Subsequently List Its Shares on Nasdaq First North, Stockholm

NOT FOR RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION IN WHOLE OR IN PART, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, IN THE UNITED STATES, AUSTRALIA, CANADA, NEW ZEALAND, HONG KONG, JAPAN, SOUTH AFRICA OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE SUCH RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION WOULD BE UNLAWFUL OR WOULD REQUIRE REGISTRATION OR ANY OTHER MEASURES. November 18, 2015 Stillfront announces its intention to raise equity capital by way of a private placement and subsequently list its shares on Nasdaq First North, Stockholm Stillfront Group AB (publ) (“Stillfront” or the “Company”), an independent creator, publisher and distributor of digital games, today announces its intention to raise equity capital by way of a private placement of shares and subsequently list its shares on Nasdaq First North, Stockholm (the “Offering”). The board of directors considers the Offering as the logical next step for Stillfront to further support its strategy and development of its business. Additional capital and the listing of its shares would, among other things, benefit Stillfront in its efforts to recruit and retain top talent, execute on its growth strategy and contribute to increased recognition and brand awareness of Stillfront. Jörgen Larsson, CEO and founder comments: “2015 has been Stillfront’s most successful year to date with an incredible global response to the pre- launch marketing of Unravel – a puzzle-platform game developed by our Swedish subsidiary Coldwood in collaboration with Electronic Arts – and the successful launch of Call of War, developed by our German subsidiary Bytro Labs. These recent successes provide further support that our business model is working, and we are now exploring ways to continue to expand”. -

Losing an Empire, Losing a Role?: the Commonwealth Vision, British Identity, and African Decolonization, 1959-1963

LOSING AN EMPIRE, LOSING A ROLE?: THE COMMONWEALTH VISION, BRITISH IDENTITY, AND AFRICAN DECOLONIZATION, 1959-1963 By Emily Lowrance-Floyd Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chairperson Dr. Victor Bailey . Dr. Katherine Clark . Dr. Dorice Williams Elliott . Dr. Elizabeth MacGonagle . Dr. Leslie Tuttle Date Defended: April 6, 2012 ii The Dissertation Committee for Emily Lowrance-Floyd certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: LOSING AN EMPIRE, LOSING A ROLE?: THE COMMONWEALTH VISION, BRITISH IDENTITY, AND AFRICAN DECOLONIZATION, 1959-1963 . Chairperson Dr. Victor Bailey Date approved: April 6, 2012 iii ABSTRACT Many observers of British national identity assume that decolonization presaged a crisis in the meaning of Britishness. The rise of the new imperial history, which contends Empire was central to Britishness, has only strengthened faith in this assumption, yet few historians have explored the actual connections between end of empire and British national identity. This project examines just this assumption by studying the final moments of decolonization in Africa between 1959 and 1963. Debates in the popular political culture and media demonstrate the extent to which British identity and meanings of Britishness on the world stage intertwined with the process of decolonization. A discursive tradition characterized as the “Whiggish vision,” in the words of historian Wm. Roger Louis, emerged most pronounced in this era. This vision, developed over the centuries of Britain imagining its Empire, posited that the British Empire was a benign, liberalizing force in the world and forecasted a teleology in which Empire would peacefully transform into a free, associative Commonwealth of Nations. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

British Intelligence Against Eoka in Cyprus 1945-1960

BRITISH INTELLIGENCE AGAINST EOKA IN CYPRUS 1945-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY NİHAL ERKAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JULY 2019 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Tülin Gençöz Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Prof.Dr.Oktay Tanrısever Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________ Prof.Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. M. Fatih Tayfur (METU, IR) _____________________ Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU,IR) _____________________ Prof. Dr. Oktay Tanrısever (METU,IR) _____________________ Prof. Dr. Gökhan Koçer (Karadeniz Teknik Uni., ULS) _____________________ Assist. Prof.Dr. Merve Seren (Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt Uni., INRE) _____________________ I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Nihal Erkan Signature : iii ABSTRACT BRITISH INTELLIGENCE AGAINST EOKA IN CYPRUS, 1945-1960 Erkan, Nihal Ph.D; Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof.Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı July 2019, 367 pages This thesis analyses the role of British intelligence activities in the fight against EOKA in Cyprus between 1945 and 1960. -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle.