Tribes in India and Arunachal Pradesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2012-13.Pdf

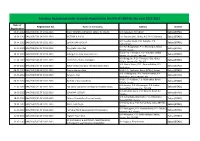

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2012-2013 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 09-04-2012 BAK/260/E/01 OF 2012-2013 JEUTY GRAMYA UNNAYAN SAMITTEE (JGUS) Vill. Batiamari, PO Kalbari Baksa (BTAD) 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/02 OF 2012-2013 VICTORY-X N.G.O. H.O. Barama (Niz-Juluki), P.O. & P.S. Barama Baksa (BTAD) Vill. Katajhar Gaon, P.O. Katajhar, P.S. 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/03 OF 2012-2013 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Baksa (BTAD) Gobardhana Vill.-Pub Bangnabari, P.O.-Mushalpur, Baksa 11-04-2012 BAK/260/E/04 OF 2012-2013 Daugaphu Aiju Afad Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. Vill. & P.O.-Tamulpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Baksa 24-04-2012 BAK/260/E/05 OF 2012-2013 Udangshree Jana Sewa Samittee Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367 Vill.-Baregaon, P.O.- Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 27-04-2012 BAK/260/E/06 OF 2012-2013 RamDhenu N.g.o., Baregaon Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Natun Sripur, P.O.- Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/07 OF 2012-2013 Natun Sripur (Sonapur /Khristan Basti) Baro Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/08 OF 2012-2013 Dodere Harimu Afat Vill.& P.O.-Laukhata, Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa (BTAD) Vill.-Goldingpara, P.O.-Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/09 OF 2012-2013 Jwngma Afat Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, Baksa (BTAD), Ass. Vill.& P.O.-Adalbari, P.S.-Mushalpur, Baksa 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/10 OF 2012-2013 Barhukha Sport Academy Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Unit 10 Tribal Ethnicity : the North-East

UNIT 10 TRIBAL ETHNICITY : THE NORTH-EAST Structure 10.0 Objectives 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Tribes and Ethnicity 10.2.1 Distinguishing Features of Tribes 10.2.2 Transformation of Tribes 10.3 Etlulic Conlposition of North-East 10.3.1 Tribal Population of North-East 10.4 Social Stratification of Tribals in the North-East 10.4.1 Mizo Administration 10.4.2 Power and Prestige Ainong Nagas 10.4 3 The Jaitltim and Khasis 10.4.4 Traditional Ratking Systems 10.5 Tribal Movements in the North-East 10.5.1 TheNagaMovement 10 5.2 Tribal Policy in Tripura 10.5.3 Tripura Struggle in Manipur 10.6 Mizoram 10.6.1 Mizo Identity 10.7 Bodo Movenlent 10.8 Tribal Ethnicity as a Basis for Stratificatioil 10.8.1 Ethnic Movements 10.8.2 Mobility and Ethnic Groups 10.9 Let Us Sum Up 10.10 Key Words 10.11 Further Readings 10.12 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 10.0 OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this unit you will be able to: Explain the relation between tribes and ethnicity; Outline the ethnic conlpositioll of the North-East; Discuss stratification of tribals in the North-East; Describe tribal movemeilts in theNorth-East: and Delineate tribal ethnicity as a basis for stratification. 10.1 INTRODUCTION The tenn tribe, which is of general use in anthropology sociology and related socio-cultural disciplines as well as journalistic writings and day-to-day general conversation, has attracted a lot of controversy about its meanings, applications and usages For one thing the tern1 has come to be used all over the world in :a wide variety of settings for a large number Tribal Ethnicity : The Yorth-East of diverse groups. -

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies MZU JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CULTURAL STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Volume IV Issue 1 ISSN:2348-1188 Editor : Dr. Cherrie Lalnunziri Chhangte Editorial Board: Prof. Margaret Ch.Zama Prof. Sarangadhar Baral Prof. Margaret L.Pachuau Dr. Lalrindiki T. Fanai Dr. K.C. Lalthlamuani Dr. Kristina Z. Zama Dr. Th. Dhanajit Singh Advisory Board: Prof. Jharna Sanyal, University of Calcutta Prof. Ranjit Devgoswami,Gauhati University Prof. Desmond Kharmawphlang, NEHU Shillong Prof. B.K. Danta, Tezpur University Prof. R. Thangvunga, Mizoram University Prof. R.L. Thanmawia, Mizoram University Published by the Department of English, Mizoram University. 1 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies 2 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies FOREWORD The present issue of MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies has encapsulated the eclectic concept of culture and its dynamics, especially while pertaining to the enigma that it so often strives to be. The complexities within varying paradigms, that seek to determine the significance of ideologies and the hegemony that is often associated with the same, convey truly that the old must seek to coexist, in more ways than one with the new. The contentions, keenly raised within the pages of the journal seek to establish too, that a dual notion of cultural hybridity that is so often particular to almost every community has sought too, to establish a voice. Voices that may be deemed ‘minority’ undoubtedly, yet expressed in tones that are decidedly -

Ziro Today, Was a Swamp

When the first Apatani came down the mountain, the land that is Ziro today, was a swamp. There lived a crocodilian species named the B'uru. The first Apatani and the B'uru lived in peaceful harmony, where the humans would even entrust the reptile to babysit their children while away gathering or hunting for food. On one such occasion, as the folklore goes, enemies of the Apatani came and took the children from the house of one of the Apatani men. The B'uru try as they might could not help prevent this treachery. The man in his anger took a Tibetan bronze plate called Talloh and smashed the B'uru to its death. After chopping it to death, the man realized, the child was not consumed by the B’uru. When the search party, finally found the child, the man was ashamed as, in his haste, he slaughtered all the B'uru in the land. He was terrified of the spirit of the B'uru and ever since hid his face using white paste made out of rice. This custom is practiced even today when the Apatani plaster the Talloh plates with white-rice paste. 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Nina Sabnani for giving me an opportunity to work under her and for her invaluable guidance, and my sincerest thanks to Paulanthony George for his help throughout the duration of the project Swati Addanki December 2015 1 CONTENTS I. Introduction II. Origins III. Process IV. People 1. Kojmama Taman 2. Punyo Tamo 3. -

Book Review North East Indian Linguistics Edited By

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 33.1 — April 2010 BOOK REVIEW NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS EDITED BY STEPHEN MOREY AND MARK POST New Delhi, Cambridge University Press India, 2008 [Hardcover, 270 + xiii pp.; ISBN: 978-81-7596-600-0.; Rs. 695/$32] Deborah King The University of Texas at Arlington North East Indian Linguistics is a collection of descriptively-oriented articles representing a sampling of North East Indian languages. It was produced under the auspices of the North East Indian Linguistic Society (NEILS)* and edited by Stephen Morey and Mark Post of the Research Centre for Linguistic Typology at La Trobe University. This work seeks to lessen the understudied status of North East Indian languages and the dearth of associated literature by presenting the results of current research in an accessible format. It includes a broad spectrum of data which must be of interest to typologists as well as any linguist with a focus on the region of North East India or the Tibeto-Burman, Indo-Aryan, Tai- Kadai, or Austroasiatic language families. Despite this addition to the literature, there remains a dire need for fieldwork and data analysis in the diverse linguistic area of North East India. Many of the contributors to this work point readers to the insufficiency of extant knowledge to support conclusions of wider significance. Rather, their work is presented simply as the opening of a door leading to varied avenues of possible further research. Nevertheless, it is heartening that over half the contributors to the volume are Indian scholars, many from the North East region, who bring their cultural and mother tongue knowledge to bear on the language of study, and who carry an intrinsic stake in the description and preservation of these understudied and sometimes endangered languages. -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

The Naga Language Groups Within the Tibeto-Burman Language Family

TheNaga Language Groups within the Tibeto-Burman Language Family George van Driem The Nagas speak languages of the Tibeto-Burman fami Ethnically, many Tibeto-Burman tribes of the northeast ly. Yet, according to our present state of knowledge, the have been called Naga in the past or have been labelled as >Naga languages< do not constitute a single genetic sub >Naga< in scholarly literature who are no longer usually group within Tibeto-Burman. What defines the Nagas best covered by the modern more restricted sense of the term is perhaps just the label Naga, which was once applied in today. Linguistically, even today's >Naga languages< do discriminately by Indo-Aryan colonists to all scantily clad not represent a single coherent branch of the family, but tribes speaking Tibeto-Burman languages in the northeast constitute several distinct branches of Tibeto-Burman. of the Subcontinent. At any rate, the name Naga, ultimately This essay aims (1) to give an idea of the linguistic position derived from Sanskrit nagna >naked<, originated as a titu of these languages within the family to which they belong, lar label, because the term denoted a sect of Shaivite sadhus (2) to provide a relatively comprehensive list of names and whose most salient trait to the eyes of the lay observer was localities as a directory for consultation by scholars and in that they went through life unclad. The Tibeto-Burman terested laymen who wish to make their way through the tribes labelled N aga in the northeast, though scantily clad, jungle of names and alternative appellations that confront were of course not Hindu at all. -

Introduction to Tangam Language and Culture

CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Tangam Language and Culture A Who and Where are the Tangam? The Tangam language [taŋam] is spoken by around 150 Tani hill-tribespeople in the Upper Siang District of the Indian State of Arunachal Pradesh, in the central Eastern Himalaya. The primary Tangam-speaking village is Kuging [kugɨŋ], a village which had twenty-six households in 2013. Nyereng [ɲereŋ] and Mayung [mayuŋ] are smaller villages in the same area in which much smaller numbers of Tangam speakers can be found. Several Tangam speakers have established households in the nearby town of Tuting [tutɨŋ], a melting pot of speakers of Bodic languages, speakers of Upper Adi varieties, and Hindi-speaking shop- keepers and Indian military personnel. However, the roots of Tangam speakers remain firmly in the village of Kuging, which is where research for this book was primarily conducted. The word “Tangam” is itself of uncertain origin, and may not have been used as an autonym for the Tangam-speaking group, or for their language, until recent times (in general in the Tani-speaking area, indi- viduals primarily identify themselves in terms of clan and village affiliations, and only secondarily – if at all – adhere to broader ethnolinguistic labels such as “Tangam” or “Adi”). Nevertheless, the label “Tangam” does not seem to be at all objectionable to Tangam speakers, and will be used in this book to refer both to the Tangam language, and to the group of people who speak it. B Linguistic and Cultural Context Tangam is a member of the Tani subgroup of Trans-Himalayan [= Sino-Tibetan or Tibeto-Burman] languages – one of the largest and most diverse language families in the world.