Downloaded From: Publisher: Raymond Williams Society (RWS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Wanna Be Me”

Introduction The Sex Pistols’ “I Wanna Be Me” It gave us an identity. —Tom Petty on Beatlemania Wherever the relevance of speech is at stake, matters become political by definition, for speech is what makes man a political being. —Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition here fortune tellers sometimes read tea leaves as omens of things to come, there are now professionals who scrutinize songs, films, advertisements, and other artifacts of popular culture for what they reveal about the politics and the feel W of daily life at the time of their production. Instead of being consumed, they are historical artifacts to be studied and “read.” Or at least that is a common approach within cultural studies. But dated pop artifacts have another, living function. Throughout much of 1973 and early 1974, several working- class teens from west London’s Shepherd’s Bush district struggled to become a rock band. Like tens of thousands of such groups over the years, they learned to play together by copying older songs that they all liked. For guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook, that meant the short, sharp rock songs of London bands like the Small Faces, the Kinks, and the Who. Most of the songs had been hits seven to ten 1 2 Introduction years earlier. They also learned some more current material, much of it associated with the band that succeeded the Small Faces, the brash “lad’s” rock of Rod Stewart’s version of the Faces. Ironically, the Rod Stewart songs they struggled to learn weren’t Rod Stewart songs at all. -

Duckie Archive

DUCKIE ARCHIVE (DUCKIE) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Various, 2018-2019. DUCKIE Duckie Archive 1996-2018 Name of Creator: Duckie Extent: 55 Files Administrative/Biographical History: Amended from the Duckie Website (2020): Duckie are lowbrow live art hawkers, homo-social honky-tonkers and clubrunners for disadvantaged, but dynamically developing authentic British subcultures. Duckie create good nights out and culture clubs that bring communities together. From their legendary 24-year weekly residency at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern to winning Olivier awards at the Barbican, they are purveyors of progressive working class entertainment who mix live art and light entertainment. Duckie combine vintage queer clubbing, LGBTQI+ heritage & social archeology & quirky performance art shows with a trio of socially engaged culture clubs: The Posh Club (our swanky showbiz palais for working class older folk, now regular in five locations), The Slaughterhouse Club (our wellbeing project with homeless Londoners struggling with booze, addiction and mental health issues), Duckie QTIPOC Creatives (our black and brown LGBTQI youth theatre, currently on a pause until we bag a funder). Duckie have long-term relationships with a few major venues including Barbican Centre, Rich Mix, Southbank Centre and the Brighton Dome, but we mostly put on our funny theatre events in pubs, nightclubs, church halls and community centres. They are a National Portfolio Organisation of Arts Council England and revenue funded by the Big Lottery Fund. Duckie produce about 130 events and 130 workshops each year - mostly in London and the South East - and our annual audience is about 30,000 real life punters. Custodial History: Deposited with Bishopsgate Institute by Simon Casson, 2017. -

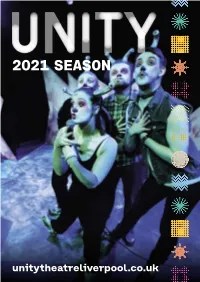

Back and Welcome to Unity's 2021 Programme of Events

2021 SEASON unitytheatreliverpool.co.uk Welcome back and welcome to Unity’s 2021 programme of events. We are delighted to finally be sharing Showcasing Local Talent with you some of the exciting productions With over 40 events and 100 artists and activities that form a special year already involved, our specially curated of work from Unity. reopening activities are a manifestation of this. Like everyone, our 2020 wasn’t quite the year we had planned. Originally Supporting Artists intended to be a landmark celebration This new season includes 22 of our 40th anniversary, instead we Merseyside-based creatives and found our doors closing indefinitely. companies who feature as part of The implications of the pandemic our Open Call Programme. Created and shutdown of venues across the UK to provide income and performance were serious and far-reaching, but they opportunity to local artists after allowed us to take stock and question a year without both, the Open Call our role as an arts organisation. celebrates these artists, their stories, communities and lives. What has emerged is a renewed commitment for Unity to provide 2021 welcomes a huge-new event space and opportunity for people series as part of our talent development to be creative, enjoy high-quality programme - Creative’pool. This will entertainment and celebrate the provide personalised training, workshops, communities of Liverpool. We want advice, exclusive events and development to continue to inspire creative opportunities to over 200 artists a year. risk and achieve a fairer, more supportive and accessible world. Access for All After a year of such uncertainty some of you may understandably be nervous about venturing into buildings. -

Scenes and Subcultures

ISSN 1751-8229 IJŽS Volume Three, Number One Realizing the Scene; Punk and Meaning’s Demise R. Pope - Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada. Joplin and Hendrix set the intensive norm for rock shows, fed the rock audience’s need for the emotional charge that confirmed they’d been at a “real” event… The ramifications were immediate. Singer-songwriters’ confessional mode, the appeal of their supposed “transparency”, introduced a kind of moralism into rock – faking an emotion (which in postpunk ideology is the whole point and joy of pop performance) became an aesthetic crime; musicians were judged for their openness, their honesty, their sensitivity, were judged, that is, as real, knowable people (think of that pompous rock fixture, the Rolling Stone interview)’. -Simon Frith, from `Rock and the Politics of Memory’ (1984: 66-7) `I’m an icon breaker, therefore that makes me unbearable. They want you to become godlike, and if you won’t, you’re a problem. They want you to carry their ideological load for them. That’s nonsense. I always hoped I made it completely clear that I was as deeply confused as the next person. That’s why I’m doing this. In fact, more so. I wouldn’t be up there on stage night after night unless I was deeply confused, too’. -John Lydon, from Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (1994: 107) `Gotta go over the Berlin Wall I don't understand it.... I gotta go over the wall I don't understand this bit at all... Please don't be waiting for me’ -Sex Pistols lyrics to `Holidays in the Sun’ INTRODUCTION: CULTURAL STUDIES What is Lydon on about? What is punk 'about’? Within the academy, punk is generally understood through the lens of cultural studies, through which punk’s activities are cast an aura of meaningful `resistance’ to `dominant’ forces. -

Equality and Diversity Within the Arts and Cultural Sector in England, 2013-16

Equality and diversity within the arts and cultural Sector in England, 2013-16: Evidence Review September 2016 Equality & Diversity: Evidence Review Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 2 Context ........................................................................................................................................ 3 3 Review Results ............................................................................................................................ 7 4 Disability ...................................................................................................................................... 9 5 Race ........................................................................................................................................... 17 6 Sex/gender ................................................................................................................................ 26 7 Age ............................................................................................................................................ 35 8 Sexual orientation ..................................................................................................................... 41 9 Gender re-assignment .............................................................................................................. 47 10 Religion and/or belief .............................................................................................................. -

Love Is GREAT Edition 1, March 2015

An LGBT guide Brought to you by for international media March 2015 Narberth Pembrokeshire, Wales visitbritain.com/media Contents Love is GREAT guide at a glance .................................................................................................................. 3 Love is GREAT – why? .................................................................................................................................... 4 Britain says ‘I do’ to marriage for same sex couples .............................................................................. 6 Plan your dream wedding! ............................................................................................................................. 7 The most romantic places to honeymoon in Britain ............................................................................. 10 10 restaurants for a romantic rendezvous ............................................................................................... 13 12 Countryside Hideaways ........................................................................................................................... 16 Nightlife: Britain’s fabulous LGBT clubs and bars ................................................................................. 20 25 year of Manchester and Brighton Prides .......................................................................................... 25 Shopping in Britain ....................................................................................................................................... -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

Re-Presenting the City

Re-presenting the City A Dramatist’s Contextualisation Of His Works On Liverpool Post - 1990 Andrew Sherlock A thesis submitted as partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 1 Contents Page A Personal Foreword 2-10 Introduction to the Publications – The Plays 11-14 Conceptual Roots and Practitioner Theory 15-34 Coherence and Context of the Body of Work 35-51 Analysis and Contextualisation of each Play Fall From Grace 52-62 Ballad Of The Sea 63-70 Walltalks 71-81 The Shankly Show 82-95 Epstein – The Man Who Made The Beatles 96-103 Thoughts and Findings, Arriving at a Research Methodology 104-115 Conclusions 116-120 Appendices Research Notes and Key References 121-128 Professional and Teaching Impact 129-131 References 132-134 2 A Personal Foreword Byford Street, Liverpool L7, taken in 1972, where I was born, though had left here by 1966. Born in 1964, the son of a plasterer and leaving for Leeds University in 1982, my formative years in Liverpool and deep early impressions of the city were shaped by the 1970s /80s. One of the few positive benefits of attending an under-funded, inner-city comprehensive school in Liverpool was perhaps the number of subjects and interests we attempted to cover and a resultant affinity for eclecticism.1 From sports to school plays to a terrible school orchestra, I had a go at everything and at times the loose structure meant that when I was caught out of 1 I attended Holt Comprehensive between 1975-82. -

Sexualities and Genders in Education

SEXUALITIES AND GENDERS IN EDUCATION Towards Queer Thriving Adam J. Greteman QUEER Series Editors STUDIES & William F. Pinar EDUCATION Nelson M. Rodriguez, & Reta Ugena Whitlock Queer Studies and Education Series editors William F. Pinar Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy University of British Columbia Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Nelson M. Rodriguez Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexual Studies The College of New Jersey Ewing, New Jersey, USA Reta Ugena Whitlock Department of Educational Leadership Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia, USA LGBTQ social, cultural, and political issues have become a defining fea- ture of twenty-first century life, transforming on a global scale any number of institutions, including the institution of education. Situated within the context of these major transformations, this series is home to the most compelling, innovative, and timely scholarship emerging at the intersec- tion of queer studies and education. Across a broad range of educational topics and locations, books in this series incorporate lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex categories, as well as scholarship in queer theory arising out of the postmodern turn in sexuality studies. The series is wide- ranging in terms of disciplinary/theoretical perspectives and methodolog- ical approaches, and will include and illuminate much needed intersectional scholarship. Always bold in outlook, the series also welcomes projects that challenge any number of normalizing tendencies within academic scholar- ship from works that move beyond established frameworks of knowledge production within LGBTQ educational research to works that expand the range of what is institutionally defined within the field of education as relevant queer studies scholarship. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14522 Adam J. -

Reviving the Queer Political Imagination

Reviving the Queer Political Imagination: Affect, Archives, and Anti-Normativity Ryan Conrad A Thesis in the Humanities Interdisciplinary Program Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2017 © Ryan Conrad, 2017 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Ryan Conrad Entitled: Reviving the Queer Political Imagination: Affect, Archives, and Anti-Normativity and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Humanities) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Rebecca Duclos Susan Knabe External Examiner Monika Gagnon External to Program Anne Whitelaw Examiner Deborah Gould Examiner Thomas Waugh Thesis Supervisor Approved by: Graduate Program Director 10 April 2017 Dean of Faculty Abstract Reviving the Queer Political Imagination: Affect, Archives, and Anti-Normativity Ryan Conrad, PhD Concordia University, 2017 Through investigating three cultural archives spanning the last three decades, this dissertation elucidates the causes and dynamics of the sharp conservative turn in gay and lesbian politics in the United States beginning in the 1990s, as well as the significance of this conservative turn for present-day queer political projects. While many argue -

Replace This with the Actual Title Using All Caps

WHEN STATES ‘COME OUT’: THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY AND THE DIFFUSION OF SEXUAL MINORITY RIGHTS IN EUROPE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Phillip Mansour Ayoub August 2013 © 2013 Phillip Mansour Ayoub WHEN STATES ‘COME OUT’: THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY AND THE DIFFUSION OF SEXUAL MINORITY RIGHTS IN EUROPE Phillip Mansour Ayoub, Ph. D. Cornell University 2013 This dissertation explains how the politics of visibility affect relations among states and the political power of marginalized people within them. I show that the key to understanding processes of social change lies in a closer examination of the ways in which—and the degree to which—marginalized groups make governments and societies see and interact with their ideas. Specifically, I explore the politics of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) visibility. For a group that many observers have referred to as “an invisible minority,” the newfound presence and influence of LGBT people in many different nation states offers fresh opportunities for the study of socio-political change and the diffusion of norms. Despite similar international pressures, why are the trajectories of socio-legal recognition for marginalized groups so different across states? This question is not answered by conventional explanations of diffusion and social change focusing on differences in international pressures, the fit between domestic and international norms, modernization, or low implementation costs. Instead, specific transnational and international channels and domestic interest groups can make visible political issues that were hidden, and it is that visibility that creates the political resonance of international norms in domestic politics, and can lead to their gradual internalization. -

LG MS 35 Ryan Conrad Collection Finding Aid

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer+ Search the Manuscript Collection (Finding Aids) Collection 4-2018 LG MS 35 Ryan Conrad Collection Finding Aid Katharine Renolds Thomas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/lgbt_finding_aids Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ryan Conrad Collection, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Collection, Jean Byers Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine, University of Southern Maine Libraries. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer+ Collection at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Search the Manuscript Collection (Finding Aids) by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JEAN BYERS SAMPSON CENTER FOR DIVERSITY IN MAINE LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANSGENDER, QUEER+ COLLECTION RYAN CONRAD COLLECTION LG MS 35 Total Boxes: 2 Mapcase Drawers: 1 Linear Feet: 2.25 By Katharine Renolds Thomas Portland, Maine October 2014 rev. 2018 Copyright 2014 by the University of Southern Maine 2 Administrative Information Provenance: The collection was donated by Ryan Conrad between 2007 and 2011. Ownership and Literary Rights: The Ryan Conrad Collection is the physical property of the University of Southern Maine Libraries. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the creator or his/her legal heirs and assigns.