Replace This with the Actual Title Using All Caps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duckie Archive

DUCKIE ARCHIVE (DUCKIE) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Various, 2018-2019. DUCKIE Duckie Archive 1996-2018 Name of Creator: Duckie Extent: 55 Files Administrative/Biographical History: Amended from the Duckie Website (2020): Duckie are lowbrow live art hawkers, homo-social honky-tonkers and clubrunners for disadvantaged, but dynamically developing authentic British subcultures. Duckie create good nights out and culture clubs that bring communities together. From their legendary 24-year weekly residency at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern to winning Olivier awards at the Barbican, they are purveyors of progressive working class entertainment who mix live art and light entertainment. Duckie combine vintage queer clubbing, LGBTQI+ heritage & social archeology & quirky performance art shows with a trio of socially engaged culture clubs: The Posh Club (our swanky showbiz palais for working class older folk, now regular in five locations), The Slaughterhouse Club (our wellbeing project with homeless Londoners struggling with booze, addiction and mental health issues), Duckie QTIPOC Creatives (our black and brown LGBTQI youth theatre, currently on a pause until we bag a funder). Duckie have long-term relationships with a few major venues including Barbican Centre, Rich Mix, Southbank Centre and the Brighton Dome, but we mostly put on our funny theatre events in pubs, nightclubs, church halls and community centres. They are a National Portfolio Organisation of Arts Council England and revenue funded by the Big Lottery Fund. Duckie produce about 130 events and 130 workshops each year - mostly in London and the South East - and our annual audience is about 30,000 real life punters. Custodial History: Deposited with Bishopsgate Institute by Simon Casson, 2017. -

National Museums in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Slovenia: a Story of Making ’Us’ Vanja Lozic

Building National Museums in Europe 1750-2010. Conference proceedings from EuNaMus, European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen, Bologna 28-30 April 2011. Peter Aronsson & Gabriella Elgenius (eds) EuNaMus Report No 1. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=064 © The Author. National Museums in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Slovenia: A Story of Making ’Us’ Vanja Lozic Summary This study explores the history of the five most significant national and regional museums in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Slovenia. The aim is to show how these museums contribute to the construction of national and other identities through collections, selections and classifications of objects of interest and through historical narratives. The three museums from Bosnia and Herzegovina that are included in this study are The National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo; which was founded in 1888 and is the oldest institution of this kind in the country; the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina founded in 1945 (Sarajevo) and the Museum of the Republic of Srpska in Banja Luka (the second largest city in BiH), which was founded in 1930 under the name the Museum of Vrbas Banovina. As far as Slovenia is concerned, two analysed museums, namely the National Museum of Slovenia (est. 1821) and the Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia (est. 1944/1948), are situated in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. The most significant periods for the creation of museums as a part of the consolidation of political power and construction of regional and/or national identities can be labelled: The period under the Austrian empire (-1918) and the establishment of first regional museums. -

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

Poland | Freedom House

Poland | Freedom House http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2012/poland About Us DONATE Blog Contact Us REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Donate FREEDOM IN THE WORLD Poland Poland Freedom in the World 2012 OVERVIEW: 2012 Parliamentary elections in October 2011 yielded an unprecedented SCORES second term for Prime Minister Donald Tusk of the center-right Civic Platform party. The Palikot Movement, an outspoken liberal party STATUS founded in 2010, won a surprising 10 percent of the popular vote, bringing homosexual and transgender candidates into the lower house of Free parliament for the first time. FREEDOM RATING After being dismantled by neighboring empires in a series of 18th-century 1.0 partitions, Poland enjoyed a window of independence from 1918 to 1939, only CIVIL LIBERTIES to be invaded by Germany and the Soviet Union at the opening of World War II. The country then endured decades of exploitation as a Soviet satellite state 1 until the Solidarity trade union movement forced the government to accept democratic elections in 1989. POLITICAL RIGHTS Fundamental democratic and free-market reforms were introduced between 1989 and 1991, and additional changes came as Poland prepared its bid for 1 European Union (EU) membership. In the 1990s, power shifted between political parties rooted in the Solidarity movement and those with communist origins. Former communist party member Alexander Kwaśniewski of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) replaced Solidarity’s Lech Wałęsa as president in 1995 and was reelected by a large margin in 2000. A government led by the SLD oversaw Poland’s final reforms ahead of EU accession, which took place in 2004. -

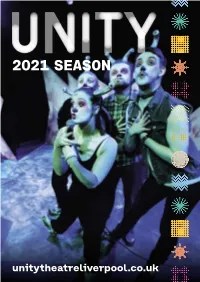

Back and Welcome to Unity's 2021 Programme of Events

2021 SEASON unitytheatreliverpool.co.uk Welcome back and welcome to Unity’s 2021 programme of events. We are delighted to finally be sharing Showcasing Local Talent with you some of the exciting productions With over 40 events and 100 artists and activities that form a special year already involved, our specially curated of work from Unity. reopening activities are a manifestation of this. Like everyone, our 2020 wasn’t quite the year we had planned. Originally Supporting Artists intended to be a landmark celebration This new season includes 22 of our 40th anniversary, instead we Merseyside-based creatives and found our doors closing indefinitely. companies who feature as part of The implications of the pandemic our Open Call Programme. Created and shutdown of venues across the UK to provide income and performance were serious and far-reaching, but they opportunity to local artists after allowed us to take stock and question a year without both, the Open Call our role as an arts organisation. celebrates these artists, their stories, communities and lives. What has emerged is a renewed commitment for Unity to provide 2021 welcomes a huge-new event space and opportunity for people series as part of our talent development to be creative, enjoy high-quality programme - Creative’pool. This will entertainment and celebrate the provide personalised training, workshops, communities of Liverpool. We want advice, exclusive events and development to continue to inspire creative opportunities to over 200 artists a year. risk and achieve a fairer, more supportive and accessible world. Access for All After a year of such uncertainty some of you may understandably be nervous about venturing into buildings. -

BEYOND TOM and TOVE SQS Queering Finnish Museums from an Intersectional Perspective 1–2/2020

BEYOND TOM AND TOVE SQS Queering Finnish Museums from an Intersectional Perspective 1–2/2020 62 Rita Paqvalén Queer Mirror Discussions ABSTRACT In this commentary, I will discuss the current interest in LGBTQ issues In this text, I will discuss the current interest in LGBTQ issues within the within the Finnish museum sector and suggest ways to address LGBTQ+ Finnish museum sector and suggest ways to address LGBTQ+ pasts pasts from an intersectional perspective. I will start with a small detour from an intersectional perspective. I will start with a small detour into my own early experience of working in a museum, and then continue into my own early experience of working in a museum, and then continue with a discussion on the history of queering museums in Finland and with a discussion of the history of queering museums in Finland and the the projects Queering the Museums (2012–2014), Finland 100 – In projects Queering the Museums (2012–2014), Finland 100 – In Rainbow Rainbow Colours (2016–2018), and Queer History Month in Finland Colours (2016–2018), and Queer History Month in Finland (2018–), in (2018–). I end my article by suggesting that we, as researchers and professionals within memory institutions, need to pay more attention which I have been involved. to what versions of LGBTQ history we are (re)producing and (re) presenting, and to what kinds of stories we collect and how. The Secret Past of Tammisaari ABSTRAKTI Tässä esseessä keskustelen suomalaisen museokentän ajankohtai- During my final years at high school, I worked as a museum guard and sesta kiinnostuksesta LHBTIQ+ kysymyksiä kohtaan, ja ehdotan tapo- guide at the local museum in a Finnish coastal town called Tammisaari ja, joilla käsitellä LHBTIQ+ vaiheita intersektionaalisesta näkökulmasta. -

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights Research Team: Juliana Martínez, PhD; Ángela Duarte, MA; María Juliana Rojas, EdM and MA. Sentiido (Colombia) March 2021 The Elevate Children Funders Group is the leading global network of funders focused exclusively on the wellbeing and rights of children and youth. We focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence. Global Philanthropy Project (GPP) is a collaboration of funders and philanthropic advisors working to expand global philanthropic support to advance the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people in the Global1 South and East. TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ...................................................................................... 4 Acronyms .................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the Directors: ......................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................... 10 Report Outline ..........................................................................................13 MOBILIZING A GENDER-RESTRICTIVE WORLDVIEW .... 14 The Making of the Contemporary Gender-Restrictive Movement ................................................... 18 Instrumentalizing Cultural Anxieties ......................................... -

Max Zachs and the Minister for Equality and Social Inclusion Opens Europride 2014

Jun 13, 2014 09:38 BST Max Zachs and the minister for Equality and Social Inclusion opens EuroPride 2014 Max Zachs, one of Britiains most well known Trans people, known from the British TV series "My Transsexual Summer" headlines the official opening of EuroPride 2014 in Oslo, Norway. At the official opening Zachs will be accompanied by Norway’s minister for Equality and Social Inclusion, Solveig Horne (in the picture), from the populist Progress party (Frp). ”I am happy and proud to attend the opening of Pride House and Euro Pride 2014 in Oslo,” says Norway’s Minister of Equality and Social Inclusion, Solveig Horne. On Friday June 20th the annual EuroPride, this year hosted by Oslo Pride, officially opens with Pride House at the House of Literature in the capitol of Norway, Oslo. ”Pride House is a unique venue and the largest LGBT political workshop organized on a voluntary basis in Norway, with over 50 different debates, lectures and workshops. During EuroPride Pride House will set politics and human rights issues in an LGBT perspective on the agenda in Norway and Europe. It is important for me as Minister for Equality to promote the event and show that we in Norway take clear position and say that lgbt-rights are human rights,” says Horne. It's about challenging ourselves and others Pride House is organized by LLH Oslo and Akershus (LLH OA), the local branch of the Norwegian LGBT organisation. Pride House is organized together with Amnesty International Norway, as well as a number of other large and small organizations. -

A Feminist Critique of Knowledge Production

This volume is the result of the close collaboration between the University of Naples “L‘Orientale” and the scholars organizing and participating to the postgraduate course Feminisms in a Transnational Perspective in Dubrovnik, Croatia. It features 15 essays that envision a feminist critique of the production Università degli studi di Napoli of knowledge that contributes today, intentionally or not, to new “L’Orientale” forms of discrimination, hierarchy control, and exclusion. Opposing the skepticism towards the viability of Humanities and Social Sciences in the era of ‘banking education’, marketability, and the so-called technological rationalization, these essays inquiry into teaching practices of non- institutional education and activism. They practice methodological ‘diversions’ of feminist intervention A feminist critique into Black studies, Childhood studies, Heritage studies, Visual studies, and studies of Literature. of knowledge production They venture into different research possibilities such as queering Eurocentric archives and histories. Some authors readdress Monique production A feminist critique of knowledge Wittig’s thought on literature as the Trojan horse amidst academy’s walls, the war-machine whose ‘design and goal is to pulverize the old forms and formal conventions’. Others rely on the theoretical assumptions of minor transnationalism, deconstruction, edited by Deleuzian nomadic feminism, queer theory, women’s oral history, and Silvana Carotenuto, the theory of feminist sublime. Renata Jambrešic ´ Kirin What connects these engaged writings is the confidence in the ethics and Sandra Prlenda of art and decolonized knowledge as a powerful tool against cognitive capitalism and the increasing precarisation of human lives and working conditions that go hand in hand with the process of annihilating Humanities across Europe. -

The Far Right in Slovenia

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF SOCIAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Far Right in Slovenia Master‟s thesis Bc. Lucie Chládková Supervisor: doc. JUDr. PhDr. Miroslav Mareš, Ph.D. UČO: 333105 Field of Study: Security and Strategic Studies Matriculation Year: 2012 Brno 2014 Declaration of authorship of the thesis Hereby I confirm that this master‟s thesis “The Far Right in Slovenia” is an outcome of my own elaboration and work and I used only sources here mentioned. Brno, 10 May 2014 ……………………………………… Lucie Chládková 2 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to doc. JUDr. PhDr. Miroslav Mareš, Ph.D., who supervised this thesis and contributed with a lot of valuable remarks and advice. I would like to also thank to all respondents from interviews for their help and information they shared with me. 3 Annotation This master‟s thesis deals with the far right in Slovenia after 1991 until today. The main aim of this case study is the description and analysis of far-right political parties, informal and formal organisations and subcultures. Special emphasis is put on the organisational structure of the far-right scene and on the ideological affiliation of individual far-right organisations. Keywords far right, Slovenia, political party, organisation, ideology, nationalism, extremism, Blood and Honour, patriotic, neo-Nazi, populism. 4 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 7 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................... -

Federalizing Legal Opportunities for LGBT Movements in the EU

LAW 2016/09 Department of Law On the ‘Entry Options’ for the ‘Right to Love’: Federalizing Legal Opportunities for LGBT Movements in the EU Uladzislau Belavusau and Dimitry Kochenov European University Institute Department of Law ON THE ‘ENTRY OPTIONS’ FOR THE ‘RIGHT TO LOVE’: FEDERALIZING LEGAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR LGBT MOVEMENTS IN THE EU Uladzislau Belavusau and Dimitry Kochenov EUI Working Paper LAW 2016/09 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the authors, the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1725-6739 © U. Belavusau & D. Kochenov 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I-50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Authors’ Contact Details Dr. Uladzislau Belavusau Department of European Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Amsterdam P.C. Hoofthuis | Spuistraat 134 1012 VB Amsterdam The Netherlands [email protected] Prof. Dimitry Kochenov Law and Public Affairs Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University 412 Robertson Hall NL 08544 Princeton USA [email protected] Abstract This paper unfolds litigation opportunities for LGBT plaintiffs embedded in EU law. It explores both established tracks and future prospects for fostering the EU’s (at times half-hearted) goodbye to heteronormativity. The paper demonstrates how American federalism theories can pave the way for the “right to love” in the European Union, whose mobile sexual citizens are equally benefiting from the “leave” and “entry options”, requiring more heteronormative states to comply with the approaches to sexuality adopted by their more tolerant peers. -

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II Volume 25 Article 1 2020 Full Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Full Issue," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 25 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol25/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Full Issue Historical Perspectives Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History December 2020 Series II, Volume XXV ΦΑΘ Published by Scholar Commons, 2020 1 Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II, Vol. 25 [2020], Art. 1 Cover image: A birds world Nr.5 by Helmut Grill https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol25/iss1/1 2 et al.: Full Issue The Historical Perspectives Peer Review Process Historical Perspectives is a peer-reviewed publication of the History Department at Santa Clara University. It showcases student work that is selected for innovative research, theoretical sophistication, and elegant writing. Consequently, the caliber of submissions must be high to qualify for publication. Each year, two student editors and two faculty advisors evaluate the submissions. Assessment is conducted in several stages. An initial reading of submissions by the four editors and advisors establishes a short-list of top papers.