Re-Presenting the City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duckie Archive

DUCKIE ARCHIVE (DUCKIE) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Various, 2018-2019. DUCKIE Duckie Archive 1996-2018 Name of Creator: Duckie Extent: 55 Files Administrative/Biographical History: Amended from the Duckie Website (2020): Duckie are lowbrow live art hawkers, homo-social honky-tonkers and clubrunners for disadvantaged, but dynamically developing authentic British subcultures. Duckie create good nights out and culture clubs that bring communities together. From their legendary 24-year weekly residency at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern to winning Olivier awards at the Barbican, they are purveyors of progressive working class entertainment who mix live art and light entertainment. Duckie combine vintage queer clubbing, LGBTQI+ heritage & social archeology & quirky performance art shows with a trio of socially engaged culture clubs: The Posh Club (our swanky showbiz palais for working class older folk, now regular in five locations), The Slaughterhouse Club (our wellbeing project with homeless Londoners struggling with booze, addiction and mental health issues), Duckie QTIPOC Creatives (our black and brown LGBTQI youth theatre, currently on a pause until we bag a funder). Duckie have long-term relationships with a few major venues including Barbican Centre, Rich Mix, Southbank Centre and the Brighton Dome, but we mostly put on our funny theatre events in pubs, nightclubs, church halls and community centres. They are a National Portfolio Organisation of Arts Council England and revenue funded by the Big Lottery Fund. Duckie produce about 130 events and 130 workshops each year - mostly in London and the South East - and our annual audience is about 30,000 real life punters. Custodial History: Deposited with Bishopsgate Institute by Simon Casson, 2017. -

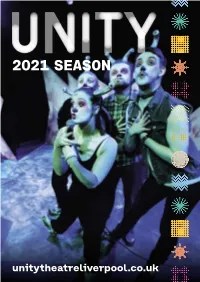

Back and Welcome to Unity's 2021 Programme of Events

2021 SEASON unitytheatreliverpool.co.uk Welcome back and welcome to Unity’s 2021 programme of events. We are delighted to finally be sharing Showcasing Local Talent with you some of the exciting productions With over 40 events and 100 artists and activities that form a special year already involved, our specially curated of work from Unity. reopening activities are a manifestation of this. Like everyone, our 2020 wasn’t quite the year we had planned. Originally Supporting Artists intended to be a landmark celebration This new season includes 22 of our 40th anniversary, instead we Merseyside-based creatives and found our doors closing indefinitely. companies who feature as part of The implications of the pandemic our Open Call Programme. Created and shutdown of venues across the UK to provide income and performance were serious and far-reaching, but they opportunity to local artists after allowed us to take stock and question a year without both, the Open Call our role as an arts organisation. celebrates these artists, their stories, communities and lives. What has emerged is a renewed commitment for Unity to provide 2021 welcomes a huge-new event space and opportunity for people series as part of our talent development to be creative, enjoy high-quality programme - Creative’pool. This will entertainment and celebrate the provide personalised training, workshops, communities of Liverpool. We want advice, exclusive events and development to continue to inspire creative opportunities to over 200 artists a year. risk and achieve a fairer, more supportive and accessible world. Access for All After a year of such uncertainty some of you may understandably be nervous about venturing into buildings. -

Ull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater

Hull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater U DPR Papers of Alan Plater 1936-2012 Accession number: 1999/16, 2004/23, 2013/07, 2013/08, 2015/13 Biographical Background: Alan Frederick Plater was born in Jarrow in April 1935, the son of Herbert and Isabella Plater. He grew up in the Hull area, and was educated at Pickering Road Junior School and Kingston High School, Hull. He then studied architecture at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne, becoming an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1959 (since lapsed). He worked for a short time in the profession, before becoming a full-time writer in 1960. His subsequent career has been extremely wide-ranging and remarkably successful, both in terms of his own original work, and his adaptations of literary works. He has written extensively for radio, television, films and the theatre, and for the daily and weekly press, including The Guardian, Punch, Listener, and New Statesman. His writing credits exceed 250 in number, and include: - Theatre: 'A Smashing Day'; 'Close the Coalhouse Door'; 'Trinity Tales'; 'The Fosdyke Saga' - Film: 'The Virgin and the Gypsy'; 'It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet'; 'Priest of Love' - Television: 'Z Cars'; 'The Beiderbecke Affair'; 'Barchester Chronicles'; 'The Fortunes of War'; 'A Very British Coup'; and, 'Campion' - Radio: 'Ted's Cathedral'; 'Tolpuddle'; 'The Journal of Vasilije Bogdanovic' - Books: 'The Beiderbecke Trilogy'; 'Misterioso'; 'Doggin' Around' He received numerous awards, most notably the BAFTA Writer's Award in 1988. He was made an Honorary D.Litt. of the University of Hull in 1985, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1985. -

Equality and Diversity Within the Arts and Cultural Sector in England, 2013-16

Equality and diversity within the arts and cultural Sector in England, 2013-16: Evidence Review September 2016 Equality & Diversity: Evidence Review Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 2 Context ........................................................................................................................................ 3 3 Review Results ............................................................................................................................ 7 4 Disability ...................................................................................................................................... 9 5 Race ........................................................................................................................................... 17 6 Sex/gender ................................................................................................................................ 26 7 Age ............................................................................................................................................ 35 8 Sexual orientation ..................................................................................................................... 41 9 Gender re-assignment .............................................................................................................. 47 10 Religion and/or belief .............................................................................................................. -

Impacts 08 Evaluation

Impacts 08 Team Dr Beatriz García, Director Ruth Melville and Tamsin Cox, Programme Managers Ann Wade, Programme Coordinator Document Reference: Impacts 08 – Miah & Adi (2009) Liverpool 08 – Centre of the Online Universe Liverpool 08 Centre of the Online Universe The impact of the Liverpool ECoC within social media environments October 2009 Report by Prof Andy Miah and Ana Adi Faculty of Business & Creative Industries Impacts 08 is a joint programme of the University of Liverpool and Liverpool John Moores University Commissioned by Liverpool City Council Impacts 08 – Miah & Adi | Liverpool 08 – Centre of the Online Universe | 2009 Executive Summary Background to the study One of the major topics of debate in media research today is whether the Internet should be treated as the dominant form of information distribution, outstripping the impact of other media, such as television, radio or print. Opinions vary about this, but numerous examples of successful online media campaigns abound, such as Barack Obama‟s use of social media during the US Presidential campaign. Today, other governments are quick to utilise similar environments, and 10 Downing Street has accounts with both YouTube and Flickr, the popular websites used for video and photo sharing respectively. Additionally, marketing and communications departments in business, industry, the arts and the media are rapidly re-organising their strategies around the rise of digital convergence and in light of evidence that demonstrates the decline (or fragmentation) of mass media audiences. These circumstances are pertinent to the hosting of European Capital of Culture by Liverpool in 2008. In short, if we want to understand how audiences were engaged during 2008, we need to complement a range of surveys and reporting with analyses of online activity, which have the potential to reflect both broader media perspectives and the views of people on the street. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

Love Is GREAT Edition 1, March 2015

An LGBT guide Brought to you by for international media March 2015 Narberth Pembrokeshire, Wales visitbritain.com/media Contents Love is GREAT guide at a glance .................................................................................................................. 3 Love is GREAT – why? .................................................................................................................................... 4 Britain says ‘I do’ to marriage for same sex couples .............................................................................. 6 Plan your dream wedding! ............................................................................................................................. 7 The most romantic places to honeymoon in Britain ............................................................................. 10 10 restaurants for a romantic rendezvous ............................................................................................... 13 12 Countryside Hideaways ........................................................................................................................... 16 Nightlife: Britain’s fabulous LGBT clubs and bars ................................................................................. 20 25 year of Manchester and Brighton Prides .......................................................................................... 25 Shopping in Britain ....................................................................................................................................... -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

They That Go Down to the Sea in Ships, That Do Business in Great Waters

5710 POL Bro FINAL 24/10/06 5:37 pm Page 1 “They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; these see the works of the lord, and his wonders in the deep” 5710 POL Bro FINAL 24/10/06 5:37 pm Page 2 5710 POL Bro FINAL 24/10/06 5:37 pm Page 3 WHERE BETTER TO DO BUSINESS THAN LIVERPOOL’S WORLD FAMOUS PORT OF LIVERPOOL BUILDING? Since its construction in 1907 it has been regarded as the perfect representation of both the city’s commercial district and its exquisite architecture. The Port of Liverpool Building offers a prestigious address, convenient location and stunning views across the mercantile city’s World Heritage waterfront. The building provides more than 155,000 sq ft of accommodation arranged on basement, ground and upper floors, with each individual floorplate offering up to 29,000 sq ft of space. 5710 POL Bro FINAL 24/10/06 5:37 pm Page 4 A celebrated landmark building, this impressive neo-classical Grade II* listed property was the first of the world renowned ‘Three Graces’ to be developed on Liverpool’s famous waterfront. Built at the beginning of the 20th century as the HQ for the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company, the Port of Liverpool Building provides bright, open plan premium office space. Accommodation on all floors is served by four passenger and two goods lifts. The building also benefits from a dedicated on-site team to assist tenants, 24hr manned security and a concierge service offered throughout the year. -

Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller

Literature to Film, lecture on Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller Atonement (2007) Universal Pictures Director: Joe Wright Screenwriter: Christopher Hampton Novel: Ian McEwan 123 minutes Cast Cecilia Tallis Keira Knightley Robbie Turner James McAvoy Briony Tallis,Briony Romola Garai Older Briony Vanessa Redgrave Briony Taliis,Briony Saoirse Ronan Grace Turner Brenda Blethyn Singing Housemaid Allie MacKay Betty Julia Ann West Lola Quincey Juno Temple Jackson Quincey Charlie Von Simpson Leon Tallis Patrick Kennedy Paul Marshall Benedict Cumberbatch Emily Tallis Harriet Walter Fiona MacGuire Michelle Duncan Sister Drummond Gina McKee Police Constable Leander Deeny Luc Cornet Jeremie Renier Police Sergeant Peter McNeil O’Connor Tommy Nettle Daniel Mays Danny Hardman Alfie Allen Pierrot,Pierrot Jack Harcourt Frenchmen Michel Vuillemoz Jackson,Jackson Ben Harcourt Frenchmen Lionel Abelanski Frank Mace Nonso Anozie Naval Officer Tobias Menzies Crying Soldier Paul Stocker Police Inspector Peter Wright Solitary Sunbather Alex Noodle Vicar John Normington Mrs. Jarvis Wendy Nottingham Beach Soldier Roger Evans, Bronson Webb, Ian Bonar, Oliver Gilbert Interviewer Anthony Minghella Soldier in Bray Bar Jamie Beamish, Johnny Harris, Nick Bagnall, Billy Seymour, Neil Maskell Soldier With Ukulele Paul Harper Probationary Nurse Charlie Banks, Madeleine Crowe, Olivia Grant, Scarlett Dalton, Katy Lawrence, Jade Moulla, Georgia Oakley, Alice Orr-Ewing, Catherine Philps, Bryony Reiss, DSarah Shaul, Anna Singleton, Emily Thomson Hospital Admin Assistant Kelly Scott Soldier at Hospital Entrance Mark Holgate Registrar Ryan Kiggell Staff Nurse Vivienne Gibbs Second Soldier at Hospital Entrance Matthew Forest Injured Sergeant Richard Stacey Soldier Who Looks Like Robbie Jay Quinn Mother of Evacuees Tilly Vosburgh Evacuee Child Angel Witney, Bonnie Witney, Webb Bem 1 Primary source director’s commentary by Joe Wright. -

Liverpool City Centre Chapter Pages from the Draft Liverpool Local Plan

The Draft Liverpool Local Plan EXTRACT CITY CENTRE CHAPTER September 2016 liverpool.gov.uk 6 Liverpool City Centre 6 43 6 6 Liverpool City Centre Context 6.1 The purpose of this chapter is to set a vision and objectives for Liverpool City Centre and specific planning policies/ approaches (both area and thematic based) which are unique to the City Centre. The Core Strategy did not include a City Centre Chapter, however policies within some of the thematic based chapters did include City Centre specific policies. Given that the City Council is now developing a Local Plan for the City it was considered appropriate to bring all the policies that are unique to the City Centre into one chapter. However, in all cases development proposals within the City Centre should be considered against all relevant city wide policies as well as specific policies within this chapter. Once adopted, the policies within this chapter will enable planning decisions to take account of city centre priorities and issues. 6.2 Given this is a consultation document, the chapter has not been fully developed. It does include a draft vision and set of draft objectives based on issues identified. The City Centre SIF has informed these. Some policies are more developed than others and for some policy areas the document only highlights issues that may need to be covered by policy.The consultation process will assist in drawing out all the key planning issues that need to be addressed in the City Centre. 6.3 It is intended that this chapter will also include a schedule of proposed City Centre allocations which will be shown on an inset Policies Map.The proposed boundary of the City Centre and Character Areas is shown on Map 1. -

University of Liverpool International College Pre-Arrival Guide Pdf 3.56MB

Pre-arrival guide for coming to the UK Welcome We are so glad you have chosen to study at University of Liverpool International College. This guide will help you through your next steps to prepare for your arrival and ensure you have everything you need for your course in the UK. We will do everything we can to make sure you are safe, supported and successful with us. Click on the page links below for useful information: What you need to do now 03 Your document list 04 What you need to pack 05 When you arrive at: the airport in the UK 06 your accommodation 07 the College 08 Prepare for your pathway course 09 Contact us 10 02 What you need to do now Step 1 Use your Confirmation of Acceptance for Studies (CAS) number to apply for your visa online, and take your documents to a visa application centre. Your Kaplan representative (or Kaplan’s Admissions, Visa and Applicant Services team, if you applied directly without an agent) can give you more information on how to apply for a visa. Step 2 If you’ve received your CAS and you know you’ll be travelling to the UK, use the accommodation guide and information on our website to choose the option you want. You can also check the available accommodation options on our UK accommodation live availability tool, then book your accommodation online through our accommodation portal. Before you receive your visa your you receive Before Step 3 You’ll receive your accommodation portal login details via email when you have an offer to study.