Failed Mothers, Monster Sons. Reading Shakespeare's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Child and the Fairy Tale: the Psychological Perspective of Children’S Literature

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 2, No. 4, December 2016 The Child and the Fairy Tale: The Psychological Perspective of Children’s Literature Koutsompou Violetta-Eirini (Irene) given that their experience is more limited, since children fail Abstract—Once upon a time…Magic slippers, dwarfs, glass to understand some concepts because of their complexity. For coffins, witches who live in the woods, evil stepmothers and this reason, the expressions should be simpler, both in princesses with swan wings, popular stories we’ve all heard and language and format. The stories have an immediacy, much of we have all grown with, repeated time and time again. So, the the digressions are avoided and the relationship governing the main aim of this article is on the theoretical implications of fairy acting persons with the action is quite evident. The tales as well as the meaning and importance of fairy tales on the emotional development of the child. Fairy tales have immense relationships that govern the acting persons, whether these are psychological meaning for children of all ages. They talk to the acting or situational subjects or values are also more children, they guide and assist children in coming to grips with distinct. Children prefer the literal discourse more than adults, issues from real, everyday life. Here, there have been given while they are more receptive and prone to imaginary general information concerning the role and importance of fairy situations. Having found that there are distinctive features in tales in both pedagogical and psychological dimensions. books for children, Peter Hunt [2] concludes that textual Index Terms—Children, development, everyday issues, fairy features are unreliable. -

Character Roles in the Estonian Versions of the Dragon Slayer (At 300)

“THE THREE SUITORS OF THE KING’S DAUGHTER”: CHARACTER ROLES IN THE ESTONIAN VERSIONS OF THE DRAGON SLAYER (AT 300) Risto Järv The first fairy tale type (AT 300) in the Aarne-Thompson type in- dex, the fight of a hero with the mythical dragon, has provided material for both the sacred as well as the profane kind of fabulated stories, for myth as well as fairy tale. The myth of dragon-slaying can be met in all mythologies in which the dragon appears as an independent being. By killing the dragon the hero frees the water it has swallowed, gets hold of a treasure it has guarded, or frees a person, who in most cases is a young maiden that has been kidnapped (MNM: 394). Lutz Rörich (1981: 788) has noted that dragon slaying often marks a certain liminal situation – the creation of an order (a city, a state, an epoch or a religion) or the ending of something. The dragon’s appearance at the beginning or end of the sacral nar- rative, as well as its dimensions ‘that surpass everything’ show that it is located at an utmost limit and that a fight with it is a fight in the superlative. Thus, fighting the dragon can signify a universal general principle, the overcoming of anything evil by anything good. In Christianity the defeating of the dragon came to symbolize the overcoming of paganism and was employed in saint legends. The honour of defeating the dragon has been attributed to more than sixty different Catholic saints. In the Christian canon it was St. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

The Father-Wound in Folklore: a Critique of Mitscherlich, Bly, and Their Followers Hal W

Walden University ScholarWorks Frank Dilley Award for Outstanding Doctoral Study University Awards 1996 The father-wound in folklore: A critique of Mitscherlich, Bly, and their followers Hal W. Lanse Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dilley This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the University Awards at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Frank Dilley Award for Outstanding Doctoral Study by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

The Bald Boy Keloğlan and the Most Beautiful Girl in the World

http://aton.ttu.edu Copyright © 2002-2003. Southwest Collection / Special Collections Library Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas The Bald Boy and the Most Beautiful Girl in the World H.B. PAKSOY © Copyright 2001 H.B. Paksoy Lubbock, Texas 2003 2 Table of Contents Keloğlan from Dream to Throne Keloğlan and His Wise Brother Tekerleme The Keloğlan Who Would Not Tell The Keloğlan Who Guarded the Door How Keloğlan Stole Köroğlu’s Horse, Kırat, for Hasan Pasa Man Persecuted Beause of Wife’s Great Beauty How Hasan and Hasan Differed from Hasan The Heavy Headed Keloğlan The Magic Bird, The Magic Fruit, and the Magic Stick The Pomegranate Thief and the Padişah’s Sons The Blind Padişah with Three Sons The Padişah’s Youngest Son as Dragon-Slayer Keloğlan as Dead Bridegroom How Keloğlan Got a Bride for a Chickpea Keloğlan and the Sheep in the Sea Keloğlan and the Sheep in the River Keloğlan and the Lost but Recovered Ring Keloğlan and the Deceived Judge The Maligned Maiden Keloğlan and the Mirror The Successful Youngest Daughter 3 The Shepherd Who Came as Ali and Returned as a Girl Keloğlan and the Girl Who Traveled Nightly to the Other World The Keloğlan and the Padişah’s Youngest Daughter The Shepherd Who Married a Princess But Became Padişah of Another Country Keloğlan Turns the Shoes How Keloğlan Drowned His Mother-in-Law Keloğlan and the Köse Miller Keloğlan and the Köse Agree Travels of Keloğlan and the Köse Keloğlan and Köse Share Bandits’ Loot Keloğlan and the Bezirgan’s Wife The Ungrateful Keloğlan and Brother Fox The Keloğlan and the Fox Keloğlan and Ali Cengiz The Adventures of Twin Brothers Preface This work may be read at random, for the pleasure they provide and the humor they contain, since the stories are self contained. -

Download Download

RISKING MASCULINITY: PLAYING FAST AND LOOSE WITH HEGEMONIC MASCULINITY IN THE HERO’S GUIDE TO SAVING YOUR KINGDOM JANICE ROBERTSON Department of English Studies University of South Africa Pretoria, South Africa [email protected] ABSTRACT In Christopher Healy’s (2012) children’s book, The hero’s guide to saving your kingdom, the idea of hegemonic masculinity is subverted in various ways. In this reinvention of four fairy tales – ‘Cinderella’, ‘Sleeping Beauty’, ‘Snow White’ and ‘Rapunzel’ – the author seems consciously to subvert the prevalent stereotypes surrounding traditional representations of the idealised, yet largely uninterrogated image of ‘Prince Charming’. All four of the princes who feature as protagonists in the book express their dissatisfaction at the prescriptive expectations that govern every aspect of their lived realities. Healy explores alternative ways of representing this type of character to modern child readers, in many cases testing the boundaries that dictate which physical characteristics and behavioural patterns are allowable in such characters. This article explores Healy’s negotiation of masculinity in the context of its intended 21st century child audience. KEYWORDS Prince Charming, masculinity studies, fairy tales, hegemonic masculinity, children’s literature, Christopher Healy 1 INTRODUCTION Christopher Healy’s The hero’s guide to saving your kingdom (2012) tells the humorous tale of the exploits of four Princes Charming and their attempts to protect their kingdoms from the evil machinations of the sorceress Zaubera. In the process, their stories and even their love-interests become disastrously entangled and the members of this mismatched quartet, ultimately referred to as ‘The League of Princes’, set out on a quest 128 © Unisa Press ISSN 0027-2639 Mousaion 32 (4) 2014 pp. -

Morphology of the Folktale This Page Intentionally Left Blank American Folklore Society Bibliographical and Special Series Volume 9/Revised Edition/1968

Morphology of the Folktale This page intentionally left blank American Folklore Society Bibliographical and Special Series Volume 9/Revised Edition/1968 Indiana University Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics Publication 10/Revised Edition/1968 This page intentionally left blank Morphology of the Folktale by V. Propp First Edition Translated by Laurence Scott with an Introduction by Svatava Pirkova-Jakobson Second Edition Revised and Edited with a Preface by Louis A. Wagner INew Introduction by Alan Dundes University of Texas Press Austin International Standard Book Number 978-0-292-78376-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 68-65567 Copyright © 1968 by the American Folklore Society and Indiana University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Twentieth paperback printing, 2009 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819 Austin, TX 78713-7819 www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html ©The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper). CONTENTS Preface to the Second Edition ix Introduction to the Second Edition xi Introduction to the First Edition xix Acknowledgements xxiii Author's Foreword XXV I. On the History of the Problem 3 II. The Method and Material 19 III. The Functions of Dramatis Personae 25 IV. Assimilations: Cases of the Double Morphological Meaning of a Single Function 66 V. Some Other Elements of the Tale 71 A. Auxiliary Elements for the Interconnection of Functions 71 B. Auxiliary Elements in Trebling 74 C. Motivations 75 VI. -

The Spirit of Play in Two Fairy Tales

Volume 19 Number 4 Article 7 Fall 10-15-1993 All Hell into His Knapsack: The Spirit of Play in Two Fairy Tales Howard Canaan Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Canaan, Howard (1993) "All Hell into His Knapsack: The Spirit of Play in Two Fairy Tales," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 19 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol19/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Examines psychological motifs and representations of the journey into maturity in two little-known Grimm fairy tales. Additional Keywords Brother Gaily (fairy tale); The Golden Bird (fairy tale); Psychological analysis of fairy tales This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

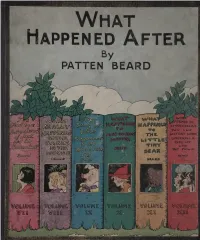

What Happened After Stories

What Happened After By PATTEN BEARD Sg|5 wtwii t WTFCtDI, J f MM>mL ' IsiiiKiSf hg^k f ««9 ; l ^0jMM L em&t» - I JSjgT J IKtljtW: WM ^£g£k. V ^AFTUR* 4 6 B^l^i© “i i^nitfe£.®*M0g1 ©nAw^ Tie <£>ea COPYRIGHT DEPOEldE*. ptPPENe® r« : 'TWO * \ iie-noes h^en2 i cmoeRfiuwx -- J R«oe off 1 -. wrn* -f line p«iHce:^f —* 5=r yy|f AT HAPPENED AFTER BY PATTEN BEARD He sighed as he gave the water to the Prince. From Secret Eleven—Jack the Giant-Killer. WHAT HAPPENED AFTER Copyright, 1929 WVi ALBERT WHITMAN & CO. Chicago, U. S. A. Printed in the U. S. A. ©CIA 15483 WlllrJilM , J |s i sH® fmmm ■ * , wMwMySi ■ . - V WHAT HAPPENED AFTER TO Page The Third Little Pig.11 Puss in Boots’ Master ..22 The Little Tiny Bear.30 CONTENTS—(Continued) WHAT HAPPENED AFTER TO Page Foxy-Woxy and Turkey-Lurkey.38 Jack and His Beanstalk.44 The Babes in the Woods.55 The Cat That Belonged to Dick Whittington.64 Sleeping Beauty.74 Red Riding Hood.87 Beauty and the Beast.94 Jack, the Giant-Killer.104 Cinderella.112 ILLUSTRATIONS Page He sighed as he gave the water to the prince.2 Cinderella’s fairy godmother said, “I am here, my dear.” . .10 Little Pig took a turkish towel and he helped the old wolf out.19 As fine a sword as the pretty penny would buy .... 29 Came face to face with Goldilocks.. .35 He was about to eat it when a gray dwarf jumped out . -

Archetypal Patterns in Fairy Tales Studies in Jungian Psychology by Jungian Analysts

Archetypal Patterns in Fairy Tales Studies in Jungian Psychology By Jungian Analysts author: Franz, Marie-Luise von. publisher: Inner City Books isbn10 | asin: 0919123775 print isbn13: 9780919123779 ebook isbn13: 9780585177021 publication date: 1997 lcc: GR550.F69 1997eb ddc: 398.2/01/9 subject: Fairy tales--Psychological aspects, Archetype (Psychology), Psychoanalysis and folklore. The Three Carnations (A Spanish tale) 27 A peasant was out in the fields one day when he saw three marvelous carnations. He broke them off and brought them to his daughter. The young girl was very happy, but one day, when she stood in the kitchen and looked at them, one fell into the coals and burned. A beautiful young man appeared then and asked her, "What's the matter with you? What are you doing?" Since she didn't answer, he said, "You don't talk to me? All right, then you can find me near the stones of the whole world." And he disappeared. She took the second carnation and threw it in the fire. Again a young man appeared before her and said, "What's the matter with you? What are you doing?" But she didn't answer. So he said, "You are not talking to me? Well, near the stones of the whole world you can find me.'' And he disappeared. Maria that was the name of the young girl took the last carnation and threw it in the fire. And again such a young man appeared, again he asked the same questions, and again he disappeared. But now Maria was sad because she had fallen in love with the last young man, and she decided after some days to go on a journey and find the stones of the whole world. -

Propp's Morphology As Narrative DNA: the 29-Function Plot Genotype of “The Robber Bridegroom”

PROPP’S MORPHOLOGY AS NARRATIVE DNA: THE 29-FUNCTION PLOT GENOTYPE OF “THE ROBBER BRIDEGROOM” MURPHY, TERENCE PATRICK YONSEI UNIVERSITY, SOUTH KOREA DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Dr. Terence Patrick Murphy Department of English Language and Literature Yonsei University, South Korea. Propp’s Morphology as Narrative DNA: The 29-Function Plot Genotype of “The Robber Bridegroom” Synopsis: In this paper, I demonstrate how a refined version of Vladimir Propp’s morphology provides the theoretical foundations for a coherent analysis of the plot genotypes of the European corpus of fairy tales. Propp’s Morphology as Narrative DNA: The 29-Function Plot Genotype of “The Robber Bridegroom” Terence Patrick Murphy (Dept of English, Yonsei University) October 8, 2014 Introduction From the time of Aristotle on, literary theorists have been interested in the subject of how the plots of stories are organized. In The Poetics, Aristotle put forward the crucial idea that a plot must possess sufficient amplitude to allow a probable or necessary succession of particular actions to produce a significant change in the fortune of the main character (57). In the early twentieth century, the Russian scholar Vladimir Propp made a substantial contribution to plot analysis when he wrote his groundbreaking study on the plot composition of the Russian fairy tale. In Morphology of the Folktale (1968), Propp put forward the radical idea that each of the plots in his corpus of a hundred Russian fairy tales consisted of a sequence of 31 functions executed in an identical order. In this way, Propp had demonstrated how it might be possible to use the idea of a continuous sequence of functions to specify Aristotle's vague but accurate understanding of the plot as a probable or necessary succession of particular actions to achieve a significant change in heroic fortune. -

Wuxia Film: a Qualitative Perspective of Chinese Legal Consciousness

Jing-Lan Lee UW Library Research Award—Project Wuxia Film: A Qualitative Perspective of Chinese Legal Consciousness Introduction With the increase of economic liberalization in the last three decades, intellectuals, optimistic China observers and members of the Chinese government view the law as a great potential social stabilizer and perhaps, more importantly, a precursor to political reform. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) first created the contemporary legal system of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to build an institutional framework that could support economic growth and development in late 1978.1 This initial system successfully facilitated economic development2 particularly in the way it took measures to establish commercial law conducive for foreign direct investment and international trade. By strengthening and developing laws and legal institutions that are more attuned to economic needs, and then expanding the scope of laws to social and political needs, the rule of law can regulate citizen behavior. It can also protect citizens’ individual rights. As such, it will become more difficult for the CCP to sustain its authoritarian single-party rule in an increasingly liberalized China as Chinese society begins to see the law as a means to defend citizens’ rights or even to facilitate eventual democratization. Indeed, several recent studies have pointed to a seeming increase in Chinese litigiousness3—indicated by the passage of hundreds of new laws, the rise in the number of legal professionals and a statistical increase in the use of courts—to argue that China is undergoing a change in legal consciousness,4 or that China sees the law as a means for social change.