Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course of Study of the Kindergarten and First Eight Grades 1910

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Western Michigan University Course Catalogs (1904-present) Western Michigan University 1910 V6 n1: Course of Study of the Kindergarten and First Eight Grades 1910 Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/course_catalogs Part of the Higher Education Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Western Michigan University, "V6 n1: Course of Study of the Kindergarten and First Eight Grades 1910" (1910). Western Michigan University Course Catalogs (1904-present). 276. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/course_catalogs/276 This Catalog is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Michigan University at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western Michigan University Course Catalogs (1904-present) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. Western State Normal School ANNOUNCEMENTS FOR 1910-11 1910 WINTER TERM Tuesday, January 4.................................... Winter Term Begins Tuesday, February 22 ............................... Washington's Birthday Friday, March 25 ......................................Winter Term Closes SPRING TERM Tuesday, April 5 ....................................... Spring Term Begins Sunday, June 19..................................... Baccalaureate Address Monday, June 20................................................ Class Day Tuesday, June 21..................................... COMMENCEMENT SUMMER TERM Monday -

The Child and the Fairy Tale: the Psychological Perspective of Children’S Literature

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 2, No. 4, December 2016 The Child and the Fairy Tale: The Psychological Perspective of Children’s Literature Koutsompou Violetta-Eirini (Irene) given that their experience is more limited, since children fail Abstract—Once upon a time…Magic slippers, dwarfs, glass to understand some concepts because of their complexity. For coffins, witches who live in the woods, evil stepmothers and this reason, the expressions should be simpler, both in princesses with swan wings, popular stories we’ve all heard and language and format. The stories have an immediacy, much of we have all grown with, repeated time and time again. So, the the digressions are avoided and the relationship governing the main aim of this article is on the theoretical implications of fairy acting persons with the action is quite evident. The tales as well as the meaning and importance of fairy tales on the emotional development of the child. Fairy tales have immense relationships that govern the acting persons, whether these are psychological meaning for children of all ages. They talk to the acting or situational subjects or values are also more children, they guide and assist children in coming to grips with distinct. Children prefer the literal discourse more than adults, issues from real, everyday life. Here, there have been given while they are more receptive and prone to imaginary general information concerning the role and importance of fairy situations. Having found that there are distinctive features in tales in both pedagogical and psychological dimensions. books for children, Peter Hunt [2] concludes that textual Index Terms—Children, development, everyday issues, fairy features are unreliable. -

Character Roles in the Estonian Versions of the Dragon Slayer (At 300)

“THE THREE SUITORS OF THE KING’S DAUGHTER”: CHARACTER ROLES IN THE ESTONIAN VERSIONS OF THE DRAGON SLAYER (AT 300) Risto Järv The first fairy tale type (AT 300) in the Aarne-Thompson type in- dex, the fight of a hero with the mythical dragon, has provided material for both the sacred as well as the profane kind of fabulated stories, for myth as well as fairy tale. The myth of dragon-slaying can be met in all mythologies in which the dragon appears as an independent being. By killing the dragon the hero frees the water it has swallowed, gets hold of a treasure it has guarded, or frees a person, who in most cases is a young maiden that has been kidnapped (MNM: 394). Lutz Rörich (1981: 788) has noted that dragon slaying often marks a certain liminal situation – the creation of an order (a city, a state, an epoch or a religion) or the ending of something. The dragon’s appearance at the beginning or end of the sacral nar- rative, as well as its dimensions ‘that surpass everything’ show that it is located at an utmost limit and that a fight with it is a fight in the superlative. Thus, fighting the dragon can signify a universal general principle, the overcoming of anything evil by anything good. In Christianity the defeating of the dragon came to symbolize the overcoming of paganism and was employed in saint legends. The honour of defeating the dragon has been attributed to more than sixty different Catholic saints. In the Christian canon it was St. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

Readers of the Round Table: the 1998 Joint Kentucky Arizona Reading Program

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 604 IR 057 328 TITLE Readers of the Round Table: The 1998 Joint Kentucky Arizona Reading Program. INSTITUTION Kentucky State Dept. for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort.; Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 357p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) Tests/Questionnaires (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; Childrens Libraries; Childrens Literature; *Creative Activities; Elementary Secondary Education; Enrichment Activities; *Library Services; *Medieval History; Parent Participation; Preschool Education; Program Guides; *Public Libraries; Questionnaires; *Reading Programs; Resource Materials; *Summer Programs; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Arizona; Kentucky ABSTRACT Intended to encourage children of all ages to read over the summer, this manual presents library-based programs, crafts, displays, and events with a medieval theme. The chapters of the manual are: (1) Introductory Materials;(2) Goals, Objectives and Evaluation;(3) Getting Started;(4) Common Program Structures;(5) Planning Timeline;(6) Publicity and Promotion;(7) Awards and Incentives;(8) Parents/Family Involvement; (9) Programs for Preschoolers, including display ideas, flannel board stories, origami, puzzle stories, songs, crafts, activities, plays, crafts, recipes, medieval clip art, and a preschool bibliography; (10) Programs for School Age Children, including entertainment programs, songs, activities, and a school age bibliography;(11) Programs for Young Adults, including activities, a medieval menu, and a young adult bibliography;(12) Special Needs; and (13) Resources, including people, companies, and materials. A master copy of a reading log and reading program evaluation form are included.(AEF) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

The Father-Wound in Folklore: a Critique of Mitscherlich, Bly, and Their Followers Hal W

Walden University ScholarWorks Frank Dilley Award for Outstanding Doctoral Study University Awards 1996 The father-wound in folklore: A critique of Mitscherlich, Bly, and their followers Hal W. Lanse Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dilley This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the University Awards at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Frank Dilley Award for Outstanding Doctoral Study by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Jonathan Zittrain's “The Future of the Internet: and How to Stop

The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jonathan L. Zittrain, The Future of the Internet -- And How to Stop It (Yale University Press & Penguin UK 2008). Published Version http://futureoftheinternet.org/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4455262 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page i The Future of the Internet— And How to Stop It YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page ii YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iii The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It Jonathan Zittrain With a New Foreword by Lawrence Lessig and a New Preface by the Author Yale University Press New Haven & London YD8852.i-x 1/20/09 1:59 PM Page iv A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. The cover was designed by Ivo van der Ent, based on his winning entry of an open competition at www.worth1000.com. Copyright © 2008 by Jonathan Zittrain. All rights reserved. Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright © Jonathan Zittrain 2008. Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

RIGHTS GUIDE RIGHTS Simon & Schuster Children’Ssimon & Schuster Publishing SIMON & SCHUSTER CHILDREN’S PUBLISHING DIVISION PICTURE BOOKS and NOVELTIES CONTACTS

Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing RIGHTS GUIDE BOLOGNA 2012 SIMON & SCHUSTER CHILDREN’S PUBLISHING DIVISION PICTURE BOOKS AND NOVELTIES CONTACTS CONTACTS FOR ALL US AND UK PICTURE BOOKS AND BOLOGNA 2012 NOVELTY TITLES WORLDWIDE AND UK FICTION: TABLE OF Tracy Phillips, Children’s Co-editions and Rights Director [email protected] CONTENTS Stephanie Purcell, Senior Rights Manager [email protected] Ruth Middleton, Children’s Rights Executive [email protected] General queries: [email protected] Simon & Schuster UK Ltd. Picture Books and Novelties Contacts 1st Floor, 222 Gray’s Inn Road, London WC1X 8HB 2 UK Tel: 00 44 207 316 1900 UK Fax: 00 44 207 316 0332 FOREIGN AGENTS WE USE INCLUDE: 3 Novelties KOREA KCC Agency Ms. Rockyoung Lee, [email protected] 13 Picture Books Imprima Agency Ms. Irene Lee, [email protected] CHINA & TAIWAN Fiction Bardon Chinese Media Agency 35 Ms. Cynthia Chang, [email protected] Ms. Jian-Mei Wang, [email protected] Big Apple Tuttlemori Agency 36 US Fiction Ms. Lily Chen, [email protected] JAPAN Japan Uni Agency Mr. Takeshi Oyama, [email protected] 60 UK Fiction 67 International Fiction Agents Contacts FOR US FICTION CONTACTS see inside back cover 2 NOVELTIES Monster House, Page 4 NOVELTIES MONSTER HOUSE Concept and Paper Engineering by Maggie Bateson Illustrated by Sarah Horne Imprint: Simon & Schuster UK A spooky pop-up monster house full of creepy frights! Join Milch and Mulch, the monster twins, as they investigate the strange creaky noises at Monster House. Meet all their friends, tiptoe along creepy corridors, and peek inside hidden cupboards. -

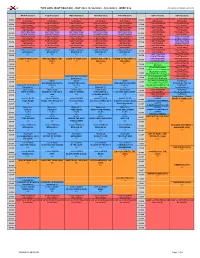

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract