Co-Management in Aby Lagoon, Côte D'ivoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

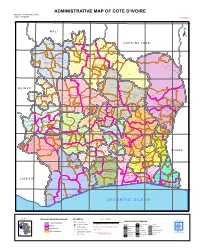

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Statistiques Du SUD COMOE

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE Union-Discipline-Travail MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE Statistiques Scolaires de Poche 2015-2016 REGION DU SUD-COMOE Sommaire Sommaire ..................................................................................... 2 Sigles et Abréviations ................................................................... 2 Méthodologie ............................................................................... 2 Introduction aux annuaires statistiques régionaux ........................ 2 1 / Résultats du Préscolaire 2015-2016 ......................................... 2 1-1 / Chiffres du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 ................................... 2 1-2 / Indicateurs du Préscolaire en 2015-2016 .............................. 2 1-3 / Préscolaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016.......... 2 2/ Résultats du Primaire 2015-2016 .............................................. 2 2-1 / Chiffres du Primaire en 2015-2016 ....................................... 2 2-2 / Indicateurs du Primaire en 2015-2016 .............................. 2 2-3 / Primaire dans les Sous-préfectures en 2015-2016................ 2 3/ Résultats du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016......................... 2 3-1 / Chiffres du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ...................... 2 3-2 / Indicateurs du Secondaire Général en 2015-2016 ................. 2 3-3 / Secondaire Général dans les Sous-préfecture en 2015-2016 ................................................................ Erreur ! Signet non défini. 4 / Annexes ................................................................................. -

Annuaire Statistique D'état Civil 2017 a Bénéficié De L’Appui Technique Et Financier De L’UNICEF

4 5 REPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D’IVOIRE Union – Discipline – Travail ------------------ MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUR ET DE LA SECURITE ---------------------------------- DIRECTION DES ETUDES, DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI-EVALUATION ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE D'ETAT CIVIL 2017 Les personnes ci-dessous nommées ont contribué à l’élaboration de cet annuaire : - Dr YAPI Amoncou Fidel MIS/DEPSE - GANNON née GNAHORE Ange-Lydie - KOYE Taneaucoa Modeste Eloge - YAO Kouakou Joseph MIS/DGAT - BINATE Mariame - GOGONE-BI Botty Maxime MIS/DGDDL - ADOU Danielle MIS/DAFM - ATSAIN Jean Jacques - ZEBA Rigobert MJDH/DECA - YAO Kouakou Charles-Elie MIS/CF - KOFFI Kouakou Roger - KOUAKOU Yao Alexis Thierry ONI - KOUDOUGNON Amone EPSE DJAGOURI DIIS - KONE Daouda SOUS-PREFECTURE DE KREGBE - TANO Hermann - BAKAYOKO Massoma INS - GNANZOU N'Guethas Sylvie Koutoua - TOURE Brahima - KOUAME Aya Charlotte EPSE KASSI ONP - IRIE BI Kouai Mathieu INTELLIGENCE MULTIMEDIA - YAO Gnekpie Florent - SIGUI Mokie Hyacinthe UNICEF 6 PREFACE Les efforts consentis par le Gouvernement pour hisser la Côte d’Ivoire au rang des pays émergents et consolider sa position dans la sous-région, ont notamment abouti à l’inscription de la réforme du système de l’état civil au nombre des actions prioritaires du Plan National de Développement (PND) 2016-2020. En effet, la problématique de l’enregistrement des faits d’état civil, constitue l’une des préoccupations majeures de l’Etat de Côte d’Ivoire pour la promotion des droits des individus, de la bonne gouvernance et de la planification du développement. Dans cette perspective, le Ministère de l’Intérieur et de la Sécurité (MIS), à travers la Direction des Etudes, de la Programmation et du Suivi-Evaluation (DEPSE), s’est engagé depuis 2012 à élaborer et éditer de façon régulière l’annuaire statistique des faits d’état civil. -

District De La Comoe

REPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D’IVIRE Union - Discipline - Travail MINISTERED’ETAT, MINISTERE DU PLAN ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT ******************* ETUDES MONOGRAPHIQUES ET ECONOMIQUES DES DISTRICTS DE COTE D’IVOIRE DISTRICT DE LA COMOE NOTE DE SYNTHESE Novembre 2015 Avec l’appui financier de l’Union Economique et Monétaire Ouest Africaine (UEMOA) Etudes monographiques et économiques des Districts de Côte d’Ivoire (PEMED-CI) District de la Comoé Note de synthèse Etudes monographiques et économiques des Districts de Côte d’Ivoire (PEMED-CI) District de la Comoé Note de synthèse SOMMAIRE Contexte ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Méthodologie ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Axe I. Territoire et démographie ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapitre 1. Caractéristiques -

Statistiques Du SUD COMOE

10 288 élèves 129 492 élèves 69 876 élèves AVANT-PROPOS La publication des données statistiques contribue au pilotage du système éducatif. Elle participe à la planification des besoins recensés au niveau du Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Technique et de la Formation Professionnelle sur l’ensemble du territoire National. A cet effet, la Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) publie, tous les ans, les statistiques scolaires par degré d’enseignement (Préscolaire, Primaire, Secondaire général et technique). Compte tenu de l’importance des données statistiques scolaires, la DSPS, après la publication du document « Statistiques Scolaires de Poche » publié au niveau national, a jugé nécessaire de proposer aux usagers, le même type de document au niveau de chaque région administrative. Ce document comportant les informations sur l’éducation est le miroir expressif de la réalité du système éducatif régional. La possibilité pour tous les acteurs et partenaires de l’école ivoirienne de pouvoir disposer, en tout temps et en tout lieu, des chiffres et indicateurs présentant une vision d’ensemble du système éducatif d’une région donnée, constitue en soi une valeur ajoutée. La DSPS est résolue à poursuivre la production des statistiques scolaires de poche nationales et régionales de façon régulière pour aider les acteurs et partenaires du système éducatif dans les prises de décisions adéquates et surtout dans ce contexte de crise sanitaire liée à la COVID-19. DRENET ABOISSO : Statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 : REGION DU SUD COMOE 2 PRESENTATION La Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) est heureuse de mettre à la disposition de la communauté éducative les statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 de la Région.Ce document présente les chiffres et indicateurs essentiels du système éducatif régional. -

DECRETE Article 1 : La Circonscription Électorale Constitue Le Référentiel Territorial De L'élection Des Députés À L'assemblée Nationale

PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D'IVOIRE Union - Discipline - Travail DECRET N° 2011-264 DU 28 SEPTEMBRE 2011 PORTANT DETERMINATION DES CIRCONSCRIPTIONS ELECTORALES POUR LA LEGISLATURE 2011-2016 LE PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE, Sur rapport du Ministre d'Etat, Ministre de l'Intérieur, Vu la Constitution ; Vu la loi n° 2000-514 du 01 août 2000 portant Code Electoral; Vu la loi n° 2004-642 du 14 décembre 2004 modifiant la loi n02001-634 du 9 octobre 2001 portant composition, organisation, attributions et fonctionnement de la Commission Electorale Indépendante (CEl) telle que modifiée par les Décisions du Président de la République n02005-06/PR du 15 juillet 2005 et n02005-11 du 29 août 2005 relatives à la la Commission Electorale Indépendante; Vu la loi n° 61-84 du 10 avril 1961 relative au fonctionnement des Départements, des Préfectures et Sous-préfectures ; Vu la loi n° 69-241 du 9 juin 1969 portant découpage administratif de la République de Côte d'Ivoire; Vu l'ordonnance n° 2008-15/PR du 14 avril 2008 portant modalités spéciales d'ajustements au code électoral pour les élections de sortie de crise; Vu l'ordonnance n° 2008-133 du 14 avril 2008 portant ajustement au Code Electoral pour les élections de sortie de crise ; Vu l'ordonnance n° 2011-224 du 16 septembre 2011 fixant le nombre de sièges de Députés à l'Assemblée Nationale; Vu le décret n° 2010-01 du 04 décembre 2010 portant nomination du Premier Ministre; Vu le décret n° 2011-101 du 01 juin 2011 portant nomination des Membres du Gouvernement; Vu le décret n° 2011-118 du 22 juin 2011 portant attributions des Membres du Gouvernement, Le Conseil des Ministres entendu DECRETE Article 1 : La circonscription électorale constitue le référentiel territorial de l'élection des députés à l'Assemblée Nationale. -

05-Sud-Comoe

ELECTION DES DEPUTES A L'ASSEMBLEE NATIONALE SCRUTIN DU 06 MARS 2021 LISTE DES CANDIDATURES RETENUES PAR CIRCONSCRIPTION ELECTORALE Region : SUD-COMOE Nombre de Sièges 178 - ABOISSO, COMMUNE 1 Couleur(s) Dossier N° Date de dépôt RASSEMBLEMENT DES HOUPHOUETISTES POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET U-00489 21/01/2021 LA PAIX VERT ORANGE DIRECTEUR INGENIEUR EN T CISSE ABOUBAKARI M S ZINSOU MARCELLIN ISIDORE M BANQUE ET CHEF DES TP FINANCE Couleur(s) Dossier N° Date de dépôt INDEPENDANT U-00496 22/01/2021 JAUNE T MIAN BOSSON JEAN FERNAND M ETUDIANT S LOHOURI JEAN CLAUDE M SANS EMPLOI Couleur(s) Dossier N° Date de dépôt PARTI DEMOCRATIQUE DE COTE D IVOIRE - RASSEMBLEMENT U-01058 22/01/2021 DEMOCRATIQUE AFRICAIN / ENSEMBLE POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA BLANCHE SOUVERAINETE DIRECTEUR DE CHEF T N'GOUAN JEREMIE ALFRED M S BENIE KAKOU JEAN-PAUL M SOCIETE D'ENTREPRISE Page 1 sur 13 T : TITULAIRE S : SUPPLEANT 178 - ABOISSO, COMMUNE Page 2 sur 13 T : TITULAIRE S : SUPPLEANT Nombre de Sièges 179 - ABOISSO, SOUS-PREFECTURE, ADAOU, ADJOUAN, KOUAKRO ET MAFERE, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES 1 Couleur(s) Dossier N° Date de dépôt INDEPENDANT U-00463 19/01/2021 JAUNE VERT GRIS T COULIBALY BAKARI M GERANT S KATCHE BOSSOMBIAN MICHEL M INSTITUTEUR Couleur(s) Dossier N° Date de dépôt INDEPENDANT U-00469 19/01/2021 ORANGE BLEU T KASSI ETCHIRY NOEL M COMPTABLE S KOUAME ANIMAND HANS HERVE M INSTITUTEUR Couleur(s) Dossier N° Date de dépôt RASSEMBLEMENT DES HOUPHOUETISTES POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET U-00490 21/01/2021 LA PAIX VERT ORANGE MEDECIN T AKA AOUELE M PHARMACIEN S KASSI AHOUBE JOSEPHINE -

CÔTE D'ivoire.Ai

vers BOUGOUNI 8° vers BOUGOUNI É 6° vers v. BOBO-DIOULASSO B KOLONDI BA SIKASSO a o g a CÔTE D'IVOIRE u GARALO in b BADOGO l f a é i l n é a k B n B a a K f KADIANA i 4° vers DIÉBOUGOU vers NANDOM n M A L I i BANFORA LAWRA u vers BOLGATANGA MANDIANA o B M HAN g a SINDOU é O g É B U R K I N A Z GOUA U D o MANANKORO é KOUÉRÉ H Tengréla O U É Pogo NIANGOLOKO GAOUA N Kanakoro MISS NI Kimbirila-Nord É ( LOROP NI V vers KANKAN B i Sa Tienko n O n a Niellé a L kar b é a o a T ni ndi É Kaouara o KAMPTI u FOLON ha BAGOU A l a m WA é Sianhala Minignan M Mbengué Diawala o N 10° Goulia K GALGOULI 10° O Barrage de É Kouto Ouangolodougou É I MALINK É É BATI R Farakoungouanan D E N G U L Kasséré MANGODARA E L Samatiguila Gbon ) é Doropo Kaniasso 848 Kolia S A V A N E S r Kimbirila- Bag a LOBI GA Gbéléban Sud oé Niofoin ba G Madinani PORO ï Sinématiali Ouango-Fitini Téhini Varalé a b Tiémé ur a Korhogo o n Seydougou 913 Ferkessédougou Kafolo K h Karakoro a Boundiali É Nassian PARC la Sirana Odienné S NOUFO Séguélon Komborodougou Tioroniaradougou 635 NATIONAL Bouna SOKOURALA 893 KABADOUGOU TCHOLOGO a Sirasso Napié b Guiembé c DIOULA DE LA C C n HA HE Bako m a e 824 l Kong G U I N É E i Dikodougou B T COMOÉ a BOUNKANI 1009 Morondo m Tafiré BOLE Dioulatiédougou a u d È vers BANDA NKWANTA S NKO Dianra o KOULANGO Booko n g 560 a a in o Djibrosso B 643 r Mont B Tortiya I B HAMBOL Boutourou BEYLA Borotou ou Tagadi WORODOUGOU Foumbolo Kotouba rédougo Koro Niakaramandougou Gansé Fé uba W O R BO B A a É Kani n Sarhala V A L L E D U B A N D A M A Z A N Z A N É -

Impact of Agricultural Input on the Quality of Water Resources: a Case of Pesticides Used in Aboisso Region (South-East of Cote D’Ivoire)

Impact of agricultural input on the quality of water resources: a case of pesticides used in Aboisso region (South-East of Cote d’Ivoire) Abstract Aboisso region is experiencing unprecedented agricultural pressure. Cultural techniques such as the use of insecticides are harming the quality of water resources. This study aims to assess the impact of insecticides on the quality of water resources in the Aboisso region. Thirty-one (31) water points (10 surface water and 21 groundwater) were sampled. The determination of physicochemical parameters as well as the multi-residue method used for insecticides analysis in the samples allowed us to achieve our objective. The results of the physicochemical analysis show that the temperature of groundwater (27.91°C) is higher than surface water temperature (26.77°C). These waters are mostly acidic with a slightly lower pH for groundwater (6.46) compared to surface water (6.54). The conductivity is higher in groundwater (average of 130.46µS/cm) as opposed to surface water (average of 43.50µS/cm). After applying the multi- residue method, the results reveal the presence of nine (9) active ingredients. In surface waters, all these molecules, except Lambda-cyhalothrin and Deltamethrin, exceed the WHO guide values (0.1µg/L). The highest concentrations recorded concern ethyl parathion and profenofos (8.24 µg/L and 8.04 µg/L respectively). In groundwater, it is rather Parathion-methyl, Profenofos, Dimethoate, Chlorpyriphos-ethyl, Lambda-cyhalothrin and Deltamethrin that are often at below WHO standards. However, the present study reveals that all of the water samples analysed are polluted by the insecticides used in the region, with some chemicals having extremely high concentrations (parathion-ethyl: 8.24 µg/L; profenofos: 8.04 µg/L). -

Region Du Sud Comoe

REGION DU SUD COMOE LOCALITE DEPARTEMENT REGION POPULATION SYNTHESE SYNTHESE SYNTHESE COUVERTURE 2G COUVERTURE 3G COUVERTURE 4G ABIATY ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 1897 ABOISSO ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 45688 ABOULIÉ ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 1639 ABOUTOU ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 1722 ABROBAKRO GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 1245 ABY ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 3318 ABY-MOHOUA ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 1402 ADAOU ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 6093 ADIAHO GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 1245 ADIAKÉ ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 19055 ADJOUAN ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 3297 ADJOUAN-MOHOUA ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 7716 ADOSSO GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 1111 AFFIÉNOU ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 6559 AFFORÉNOU-POSTE ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 355 AHIGBÉ-KOFFIKRO ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 14928 AKAKRO ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 5853 AKOUNOUGBÉ ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 3346 AKPAGNE-POSTE ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 232 AKRESSI ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 2645 AKROABA-AKOUDJÉKOA GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 2906 AKROABA-BÉNIÉKOA GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 843 ALLAKRO TIAPOUM SUD-COMOE 3870 ALLANGOUANOU TIAPOUM SUD-COMOE 838 ALLIÉKRO ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 418 ALOHORÉ GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 2653 REGION DU SUD COMOE AMANIKRO ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 2507 AMOAKRO ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 695 ANDJÉ TIAPOUM SUD-COMOE 377 ANGA ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 972 ANGBOUDJOU ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 1020 ANZÉ-ASSANOU ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 262 APPOUASSO ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 5880 ASSÉ GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 3034 ASSÉ MAFIA GRAND-BASSAM SUD-COMOE 300 ASSINIE-FRANCE ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 1729 ASSINIE-MAFIA ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 5661 ASSINIE-SAGBADOU ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 1014 ASSOMLAN ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 1075 ASSOUANKAKRO ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 438 ASSOUBA ABOISSO SUD-COMOE 5802 ASSOUINDÉ ADIAKÉ SUD-COMOE 5766 ASSUÉ -

Impacts of Agrochemicals on Water Quality Parameters in Aboisso Region (South-East of Cote D’Ivoire)

Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology 39(46): 1-19, 2020; Article no.CJAST.63546 ISSN: 2457-1024 (Past name: British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, Past ISSN: 2231-0843, NLM ID: 101664541) Impacts of Agrochemicals on Water Quality Parameters in Aboisso Region (South-East of Cote d’Ivoire) Assouman Amadou1*, Kpan Oulai Jean-Gautier2, Gnamba Franck Maxime2, Oga Yéï Marie Solange1 and Biémi Jean1 1Laboratoire des Sciences et Techniques de L’eau Et De L’environnement (LSTEE), Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny de Cocody-Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. 2Département des Géosciences, Université Péléféro Gon Coulibaly de Korhogo, Côte d’Ivoire. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author AA designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors KOJG and GFM managed the analyses of the study. Authors OYMS and BJ managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/CJAST/2020/v39i4631167 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Tushar Ranjan, Bihar Agricultural University, India. Reviewers: (1) Adams Sadick, CSIR-Soil Research Institute, Ghana. (2) Jonah Udeme Effiong, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/63546 Received 15 October 2020 Original Research Article Accepted 19 December 2020 Published 31 December 2020 ABSTRACT Aboisso region is experiencing unprecedented agricultural activities. Cultural techniques such as the use of insecticides are harming the quality of water. This study aims to assess the impact of insecticides on the water quality in the Aboisso region.