The Iranian Perception of the British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultuling of "Insult" in My Uncle Napoleon and English Equivalents: a Corpus-Based Study

Language and Translation Studies, Vol. 53, No.4 2 The Cultuling of "Insult" in My Uncle Napoleon and English Equivalents: A Corpus-Based Study Masoumeh Mehrbi 1 Department of Linguistics and TEFL, Ayatollah Boroujerdi University, Boroujerd. Iran Behrooz Mahmoodi Bakhtiari Department of Performing Art, Fine Art, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran Received: 23 March 2020 Accepted: 23 May 2020 Abstract Given the significance of cultural considerations and cultural categories in determining appropriate translation equivalents, this paper discusses the cultuling of ‘insult’ based on Iraj Pezeshkzad’s My Uncle Napoleon translated by Dick Davis into English and the original Persian version of the novel where there can be found so many linguistic segments containing or conveying insulting connotations. Cultuling refers to those pieces of language which are the manifestation of cultural concepts since language is the representation of culture, and it is also bounded by culture. The investigation of insults just like cursing and swearing are common issues in language and culture, especially when considered in two languages. That is the real motive for conducting the present inquiry, and more importantly, perfect translation needs cultural knowledge. As for the research methodology, Del Hymes’s (1967) SPEAKING model as a discourse/ qualitative method as well as frequency effects as the quantitative method were employed. Applying this methodology, the speakers’ motivation for the use of insults is found in this culture. Moreover, the cultural differences leading to and manifested in linguistic differences are discussed. Meanwhile, strategies for appropriate equivalents were laid out. The results are of use and value for the entrenchment of the cognitive-cultural views of translation studies as well as socio-cultural studies of linguistic issues. -

Eulogy for Dr. Ehsan Yarshater•

178 November - December 2018 Vol. XXVII No. 178 Remembering Professor Ehsan Yarshater • Iranian Novels in Translation • PAAIA National Survey 2018 • Second Annual Hafez Day 2018 • Mehregan Celebration • Nutrition During Pregnancy • Menstrual Cramps • Eulogy For Dr. Ehsan Yarshater • No. 178 November-December 2018 1 178 By: Shahri Estakhry Since 1991 Persian Cultural Center’s Remembering Professor Ehsan Yarshater (1920-2018) Bilingual Magazine Is a bi - monthly publication organized for th When we heard the news of the passing of Professor Ehsan Yarshater on September 20 , our last literary, cultural and information purposes issue of Peyk was at the print shop and we could not pay our deepest respect in his memory at Financial support is provided by the City of that time. Although, many tributes in Persian and English have been written in his memory, we San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture. too would like to remember him with great respect and great fondness. Persian Cultural Center I had the pleasure of meeting him and his wife, Latifeh, in 1996 when, at the invitation of the 6790 Top Gun St. #7, San Diego, CA 92121 Persian Cultural Center they came to San Diego and he gave a talk about the Persian civilization Tel (858) 552-9355 and the Encyclopedia Iranica. While listening to him, mesmerized by his presentation, there was Fax & Message: (619) 374-7335 Email: [email protected] no doubt for anyone that here was a man of true knowledge and great integrity. How privileged www.pccsd.org we were to be in the audience. He was an extraordinary man of accomplishments, easy to respect, easy to hold in your heart with adoration. -

Read the Introduction

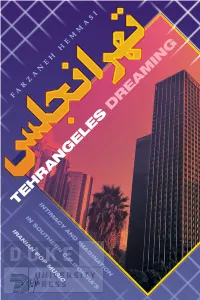

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

GHAREHGOZLOU, BAHAREH, Ph.D., August 2018 TRANSLATION STUDIES

GHAREHGOZLOU, BAHAREH, Ph.D., August 2018 TRANSLATION STUDIES A STUDY OF PERSIAN-ENGLISH LITERARY TRANSLATION FLOWS: TEXTS AND PARATEXTS IN THREE HISTORICAL CONTEXTS (261 PP.) Dissertation Advisor: Françoise Massardier-Kenney This dissertation addresses the need to expand translation scholarship through the inclusion of research into different translation traditions and histories (D’hulst 2001: 5; Bandia 2006; Tymoczko 2006: 15; Baker 2009: 1); the importance of compiling bibliographies of translations in a variety of translation traditions (Pym 1998: 42; D’hulst 2010: 400); and the need for empirical studies on the functional aspects of (translation) paratexts (Genette 1997: 12–15). It provides a digital bibliography that documents what works of Persian literature were translated into English, by whom, where, and when, and explores how these translations were presented to Anglophone readers across three historical periods—1925–1941, 1942–1979, and 1980–2015— marked by important socio-political events in the contemporary history of Iran and the country’s shifting relations with the Anglophone West. Through a methodical search in the library of congress catalogued in OCLC WorldCat, a bibliographical database including 863 editions of Persian-English literary translations along with their relevant metadata—titles in Persian, authors, translators, publishers, and dates and places of publication—was compiled and, through a quantitative analysis of this bibliographical data over time, patterns of translation publication across the given periods -

Suggested Reading

READING GUIDE Iran Here is a brief selection of favorite, new and hard-to-find books, prepared for your journey. Essential Reading Package Helen Loveday Odyssey Guide Iran Hooman Majd IRN20 | 2016 | 464 pages | PAPER The Ayatollah Begs to Differ Strong on Iran's many archaeological sites, this IRN67 | 2009 | 272 pages | PAPER illustrated, authoritative guide includes chapters on Islamic art and architecture, history and religion. An American journalist (who translated for Ahmadinejad at the UN), grandson of an eminent $24.95 ayatollah and the son of an Iranian diplomat, Majd introduces Persian culture and modern Iran Louisa Shafia with insight and depth. The New Persian Kitchen $16.00 ARB187 | 2013 | 208 pages | HARD COVER Acclaimed chef and blogger Louisa Shafia explores Abrahamian Ervand her Iranian heritage by reimagining classic Persian recipes from a fresh, vegetable-focused perspective. A History of Modern Iran IRN65 | 2008 | 264 pages | PAPER Her vibrant recipes feature ingredients like rose petals, dried limes, tamarind and sumac, in surpri A well-written, reliable account of 20th-century Iranian history which traces the collapse of the Shah’s regime $24.99 and the formation of the Islamic Republic. Yasmin Khan $30.99 The Saffron Tales, Recipes from the Persian Kitchen Stuart Williams Culture Smart! Iran IRN139 | 2016 | 240 pages | HARD COVER Interweaving stories and recipes from all corners of IRN64 | 2016 | 168 pages | PAPER Iran, British-Iranian cook Yasmin Khan shares A concise, well-illustrated and practical guide to exceptionally delicious recipes from the ordinary local customs, etiquette and culture. Iranian kitchen, including Fesenjoon (chicken with walnuts and pomegranates), Tahcheen (baked $11.99 saffron and aubergine rice) and some mouth-watering desserts. -

Reading Lolita in Tehran

Reading Lolita in Tehran: Nabokov could not have wished for more attentive students than those who met on Thursday mornings in 1995 at the Tehran apartment of Azar Nafisi to study English literature. Nafisi, who had recently resigned her position as Professor of English Literature at the University of Tehran, expertly guided a group of seven young women in discussions of works such as Pride and Prejudice, The Great Gatsby, and Daisy Miller. Lolita, however, was the class favorite. To them, the Islamic Republic was like Humbert Humbert and they were like Dolores Haze—controlled by an authority who confiscates their individual identities and replaces them with a cipher of his own imagination. The slightest provocation, a hair out of place, a bared ankle, maddens Humbert just as it does their own tormentors. In the alternative world of Nafisi's apartment, where not the horrors and humiliations waiting in the street below but the mountains of Tehran were reflected in the antique oval mirror that hung on the far wall of the living room, Nafisi and her group of hand- picked students used literature, as Nabokov had, to transcend the unacceptable realities of a preposterous life and find a place where art, tenderness, and beauty prevailed. Reading Lolita in Tehran is Nafisi's account of the years she spent in Iran trying to come to terms with the totalitarian regime that came to power in 1979. By the time the Islamic Republic had so circumscribed the lives of women that attending an all-girl literature class at the home of a professor might require an alibi, "Knowledge nicely browned" was no longer an option. -

Getting Started WHEN to GO When Deciding When to Go to Iran You Must First Work out Where You’D Like to Go

© Lonely Planet Publications 15 Getting Started WHEN TO GO When deciding when to go to Iran you must first work out where you’d like to go. Temperatures can vary wildly: when it’s -5°C in Tabriz it might be 35°C in Bandar Abbas, but for most people spring and autumn are the most pleasant times to visit. At other times, the seasons have advantages and disadvantages depending on where you are. For example, the most agreeable time to visit the Persian Gulf coast is during winter, when the humidity is low and temperatures mainly in the 20s. At this time, however, the more elevated northwest and northeast can be freezing, with mountain roads impassable due to snow. Except on the Persian Gulf coast, winter See Climate Charts ( p376 ) nights can be bitterly cold, but we think the days (often clear and about for more information. 15°C in much of the country) are more pleasant than the summer heat. And when we say ‘heat’, we mean it. Between May and October tem- peratures often rise into the 40s, and in the deserts, southern provinces DON’T LEAVE HOME WITHOUT...READING THIS FIRST The best preparation for visiting Iran is to read as much of the front and back chapters in this guide as you can. If you can’t read everything, at least read the following: How do I get a visa and how long can I stay? ( p393 ) Credit cards and travellers cheques don’t work. Bring cash. ( p387 ) This money is confusing. Rials or toman? (p387 ) Prices will be higher than what we have in this book; see p25 and p388 . -

Introduction 1 Land and People

Notes Introduction 1. Oleg Grabar provides a useful summary of the evolution of Islamic institutions in The Formation of Islamic Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987). 1 Land and People 1. For an overview of both prerevolutionary and postrevolutionary Iranian cinema, including discussion of Bashu, see Mamad Haghighat, Histoire du cinéma iranien. (Paris: BPI Centre Georges Pompidou, 1999), and Hormuz Kéy, Le cinema iranien (Clamency: Nouvellle Imprimerie Labellery, 1999). In English, Richard Tapper has collected a series of analytical essays about film in the Islamic Republic. See Richard Tapper, ed., The New Iranian Cinema (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2002). 2. Bernard Hourcade, Hubert Mazurek, Mohammad-Hosseyn Papoli-Yazdi, and Mahmoud Taleghani provide a wealth of valuable data regarding demography, religion, land use, education, and language based upon Iranian official statistics in Atlas d’Iran (Paris: Reclus, 1998). 3. English-language translations of Persian poetry are plentiful. For an interesting account of the influence of the Persian language, see Shahrokh Meskoob, Iranian Nationality and the Persian Language, John Perry, ed., Michael Hillmann, trans. (Washington: Mage Publishers, 1992). 4. For the best coverage of Iranian geography, see W.B. Fisher, ed., The Cambridge History of Iran: Volume I: The Land of Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968). 5. Edward Stack, Six Months in Persia, Volume I (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1882), p. 9. 6. Rula Jurdi Afrasiab, “The Ulama of Jabal ‘Amil in Safavid Iran, 1501–1736: Marginality, Migration, and Social Change,” Iranian Studies, 27: 1–4 (1994), pp. 103–122. 7. Article XII. See Hamid Algar, trans., “Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran” (Berkeley: Mizan Press, 1980), p. -

Dissertation Complete

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The State of Resistance: National Identity Formation in Modern Iran Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/83x412wv Author Rad, Assal Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The State of Resistance: National Identity Formation in Modern Iran DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Assal Rad Dissertation Committee: Professor Touraj Daryaee, Co-Chair Professor Mark LeVine, Co-Chair Professor Roxanne Varzi 2018 © 2018 Assal Rad TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ix CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1 I. Introduction 1 II. Framework 4 III. Background 10 IV. What’s Been Said 13 V. What’s To Come 26 VI. Conclusion 37 CHAPTER 2: The Foreign Shah and the Failure of Pahlavi Nationalism 39 I. Introduction 39 II. Background: Foreign Power and Iranian Decline 40 III.I. The Shah’s Nationalism: Revolution, Independence and Persian Dominion 47 III.II. The Shah’s Naiveté: Disconnect and Foreignness 57 III.III. 1971: The Party of the Century and the Apex of IGnorance 64 IV.I. The Opposition: ResistinG Imperialism 67 IV.II. Khomeini’s LeGacy: A Revolution and Modern Iran 75 V. Conclusion 79 CHAPTER 3: The Islamic Republic and Its Culture of Resistance 82 I. Introduction 82 II. 1979: The Islamic Republic’s Permanent Revolution and Iranian Independence 89 III.I. -

Download My Uncle Napoleon PDF

Download: My Uncle Napoleon PDF Free [128.Book] Download My Uncle Napoleon PDF By Iraj Pezeshkzad, afterword) Dick Davis (translator My Uncle Napoleon you can download free book and read My Uncle Napoleon for free here. Do you want to search free download My Uncle Napoleon or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #My Uncle Napoleon | #105338 in Audible | 2014-01-30 | Format: Unabridged | Original language: English | Running time: 1226 minutes | |8 of 8 people found the following review helpful.| But what if the murder victim refuses to come along? | By Geoff Puterbaugh |What a wonderful book this is! Funny and heart-warming, indeed. On page one a 13- year-old boy falls in love with the beautiful black eyes of his cousin, and he tells the rest of the story. The characters are not "realistic." Heaven forfend! They are loving and comic exaggerations of real Per "The existence in Persian literature of a full-scale, abundantly inventive comic novel that involves a gallery of varied and highly memorable characters, not to mention scenes of hilarious farcical mayhem, may come as a surprise to a Western audience used to associating Iran with all that is in their eyes dour, dire and dreadful." (From the Preface) Set in a garden in Tehran in the early 1940s, where three families live under the tyranny of a paranoid patriarch, [839.Book] My Uncle Napoleon PDF [688.Book] My Uncle Napoleon By Iraj Pezeshkzad, afterword) Dick Davis (translator Epub [780.Book] My Uncle Napoleon By Iraj Pezeshkzad, afterword) Dick Davis (translator Ebook [822.Book] My Uncle Napoleon By Iraj Pezeshkzad, afterword) Dick Davis (translator Rar [654.Book] My Uncle Napoleon By Iraj Pezeshkzad, afterword) Dick Davis (translator Zip [071.Book] My Uncle Napoleon By Iraj Pezeshkzad, afterword) Dick Davis (translator Read Online Free Download: My Uncle Napoleon pdf. -

Copyright by Blake Robert Atwood 2011

Copyright by Blake Robert Atwood 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Blake Robert Atwood certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: RE-ENVISIONING REFORM: FILM, NEW MEDIA, AND POLITICS IN POST-KHOMEINI IRAN Committee: M.R. Ghanoonparvar, Supervisor Kamran Aghaie Kristen Brustad Mia Carter Michael C. Hillmann Nasrin Rahimieh RE-ENVISIONING REFORM: FILM, NEW MEDIA, AND POLITICS IN POST-KHOMEINI IRAN by Blake Robert Atwood, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation was made possible by the hard work and support of a very devoted group of advisors, friends, and family members, and I owe many thanks. I have had the great fortune of working with an amazing and encouraging dissertation committee. I am especially grateful to M.R. Ghanoonparvar, who has supervised my work over the last five years with patience and steadfastness; his unyielding belief in my abilities as a teacher and a scholar made me feel at home in the field of Persian studies. Michael Craig Hillmann has pushed me to be rigorous in my scholarship, and I appreciate his willingness to share with me his vast knowledge of and enthusiasm for Persian literature. Kamran Aghaie’s open door meant that I often ran to him first with good news and bad. He gave generously of his time, knowledge and advice, and I cannot begin to express my thanks to him. -

Chapter 2 the Historical Geopolitics of Oil in Khuzestan

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/28983 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Ehsani, Kaveh Title: The social history of labor in the Iranian oil industry : the built environment and the making of the industrial working class (1908-1941) Issue Date: 2014-10-02 Chapter 2 The Historical Geopolitics of Oil in Khuzestan The Post War Landscape of Unanticipated Outcomes (1918-1926) In the wake of WWI, for the first time, Britain appeared as the absolute master of the situation in Iran and the Persian Gulf1. All its major imperial rivals in the region - the German, Ottoman, and Russian empires - had collapsed, thus eliminating the long maintained anxiety about defending the Indian colony from hostile encroachments. The Royal Navy dominated the Persian Gulf having subjugated the littoral Arab city states as its vassals, and the British Army surrounded the prized oil installations of Khuzestan with more than a half a million troops that continued to be deployed in the Near and Middle East2. In Iran the Qajar state was in a position of near total dependence on the good graces of His Majesty’s Government. The state finances were good as bankrupt and its outdated bureaucracy was close to total disarray3. The fragmented, mal-trained, and small military forces were being paid not out of an empty treasury but from loans obtained with ever more difficulty from the country’s only, British owned, Imperial Bank4. Given the increasingly desperate state of the country after the Constitutional 1 See Roger Adelson, London and the Invention of the Middle East: Money, Power, and War, 1902- 1922 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995); Abd al-Reza Houshang Mahdavi, Siyasat-e Khareji-e Iran dar Dowran-e Pahlavi, 1300-1357 (Tehran: Alburz, 2001), 1–52; Abd al-Reza Houshang Mahdavi, Sahnehayee az Tarikh Mo’aser Iran (Tehran: Elmi, 1998), 185–204; Houshang Sabahi, British Policy in Persia, 1918-1925 (London: Frank Cass, 1990); W.