Please Scroll Down for Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reps. Knollenberg, David Law, Moss, Bieda, Casperson, Clack, Condino

Reps. Knollenberg, David Law, Moss, Bieda, Casperson, Clack, Condino, Dean, DeRoche, Garfield, Hildenbrand, Horn, Rick Jones, LaJoy, Palmer, Pastor, Proos, Scott, Stahl and Wojno offered the following resolution: House Resolution No. 159. A resolution to urge the President of the United States, the United States Congress and the United States Department of State to consult with appropriate officials in Syria, Lebanon, and the Palestinian Authority regarding the status of missing Israeli soldiers and demand the immediate and unconditional release of three Israeli soldiers currently believed to be held by Hamas and Hezbollah. Whereas, The United States Congress expressed its concern for Israeli soldiers missing in Lebanon and the Hezbollah-controlled territory of Lebanon in Public Law 106-89 (113 Stat. 1305; November 8, 1999) which required the Secretary of State to probe into the disappearance of Israeli soldiers with appropriate government officials of Syria, Lebanon, the Palestinian Authority, and other governments in the region, and to submit to the Congress reports on those efforts and any subsequent discovery of relevant information; and Whereas, Israel completed its withdrawal from southern Lebanon on May 24, 2000. On June 18, 2000, the United Nations Security Council welcomed and endorsed United Nations Secretary- General Kofi Annan's report that Israel had withdrawn completely from Lebanon under the terms of United Nations Security Council Resolution 425 (1978). Nearly five years later, Israel completed its withdrawal from Gaza on September 12, 2005; and Whereas, On June 25, 2006, Hamas and allied terrorists crossed into Israel to attack a military post, killing two soldiers and wounding a third, Gilad Shalit, who was kidnapped. -

Congressional Record—House H7762

H7762 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE July 12, 2007 we will proceed with next week’s work and Defense; Commander, Multi-Na- ried Karnit when he was captured, and next week. tional Forces—Iraq; the United States his wife had to spend their 1-year anni- f Ambassador to Iraq; and the Com- versary alone, wondering where her mander of United States Central Com- husband was and what condition he was HOUR OF MEETING ON TOMORROW mand. in. His family and friends wrote: AND ADJOURNMENT FROM FRI- GEORGE W. BUSH. ‘‘He’s a loving, caring person, always DAY, JULY 13, 2007 TO MONDAY, THE WHITE HOUSE, July 12, 2007. ready to offer a helping hand in any JULY 16, 2007 f situation. He is a man of principles and Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, I ask values, knowledgeable in many varied unanimous consent that when the SPECIAL ORDERS subjects.’’ House adjourns today, it adjourn to The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under Unfortunately, Eldad and Udi are not meet at 4 p.m. tomorrow, and further, the Speaker’s announced policy of Jan- alone among Israel’s missing soldiers. when the House adjourns on that day, uary 18, 2007, and under a previous Three weeks before their capture, it adjourn to meet at 12:30 p.m. on order of the House, the following Mem- Hamas kidnapped IDF soldier Gilad Monday, July 16, 2007, for morning- bers will be recognized for 5 minutes Shalit. The Shalit family has also met hour debate. each. with many communities across the The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. f United States, urging people to remem- ELLISON). -

The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017

The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 150 THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 150 The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Tel. 972-3-5318959 Fax. 972-3-5359195 [email protected] www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 May 2018 Cover image: Soldier from the elite Rimon Battalion participates in an all-night exercise in the Jordan Valley, photo by Staff Sergeant Alexi Rosenfeld, IDF Spokesperson’s Unit The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies is an independent, non-partisan think tank conducting policy-relevant research on Middle Eastern and global strategic affairs, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and regional peace and stability. It is named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace laid the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. -

Insights from the Second Lebanon War

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Browse Reports & Bookstore TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. All Glory Is Fleeting Insights from the Second Lebanon War Russell W. Glenn Prepared for the United States Joint Forces Command Approved for public release; distribution unlimited NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE The research described in this report was sponsored by the United States Joint Forces Command Joint Urban Operations Office. -

Analysis: 'Disproportion Has Always Been the Name of the Game' | Jerusalem Post Page 1 of 2

Analysis: 'Disproportion has always been the name of the game' | Jerusalem Post Page 1 of 2 Want To Quit Your Job? The Jerusalem Post Mobile Graphic Designer Support Israel Earn 3K-5K Per Week-From Home Breaking news from Israel Stay up Adobe Photoshop CS Quark XPress Help Yad Ezra VeShulamit. Feeding Let Me Show You How to date Kамтес 1-800-22-22-28 Israel's Hungry Children & Families www.1kdailyjob.com mobile.jpost.com www.kamtec.com www.yad-ezra.org Analysis: 'Disproportion has always been the name of the game' Jun. 18, 2008 abe selig , THE JERUSALEM POST Trading Lebanese terrorist Samir Kuntar for captured IDF reservists Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev is important even if the two soldiers are no longer alive, Yoram Schweitzer of the Institute for National Security Studies said on Wednesday, as the deal was apparently moving through its final stages. "Disproportion has always been the name of the game," Schweitzer said, alluding to the possibility that the government wasn't negotiating with Hizbullah for the soldiers themselves, but for their remains. He is a senior research fellow and director of the Program on Terrorism and Low Intensity Conflict at the institute. But the prospect of such a deal raises questions as to how the Israeli public will respond if the two IDF soldiers are dead, adding a heartrending tone to this final chapter of the Second Lebanon War, which was waged to bring them home in the first place. "Even if they are dead, which I hope they're not," Schweitzer continued, "we will give two families knowledge of the fate of their loved ones, and I wouldn't underestimate that fact. -

Reading Three-.Cwk

Reading 3: Six-Day War THE BATTLES BEGIN Because Israel feared fighting on three fronts (Egyptian, Jordanian, and Syrian), and because it preferred that fighting take place in Arab rather than Israeli territory, Israel decided to strike first. On the morning of June 5 the Israeli air force attacked Egypt, the largest force in the region. The timing of the attack, 8:45 AM, was designed to catch the maximum number of Egyptian aircraft on the ground and to come when the Egyptian high command was stuck in traffic between homes and military bases. The Israeli aircraft took evasive measures to elude Egyptian radar and approached from directions that were not anticipated. The surprise was complete. Within hours of the strike, the Israelis, who focused their attacks on military and air bases, had destroyed 309 of the 340 total combat aircraft belonging to the Egyptians. Israeli ground forces then moved into the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip, where they fought Egyptian units. Egyptian casualties were heavy, but Israel suffered only minimal casualties. War was not far behind on Israel’s eastern front. Israel had conveyed a message to King Hussein of Jordan asking him to stay out of the conflict, but on the first morning of the war Nasser called Hussein and encouraged him to fight. Nasser reportedly told Hussein that Egypt had been victorious in the morning’s fighting—an illusion the Egyptian public believed for several days. At 11:00 AM Jordanian troops attacked the Israeli half of Jerusalem with mortars and gunfire and shelled targets in the Israeli interior. -

The Israeli Defense Forces: an Organizational Perspective

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1990-03 The Israeli Defense Forces: an organizational perspective Green, Matthew John Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/30693 DIJT FIlE COPY 0NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL 4 Monterey, California CD DTIC S EECTE f SEP IITHESIS THE ISRAELI DEFENSE FORCES: AN ORGANIZATIONAL PERSPECTIVE by Matthew John Green March 1990 Thesis Co-Advisors: Carl R. Jones Ralph H. Magnus Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 90 09 05 021 Unclassified SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Oo. 070rove i. REPORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION lb. RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS Unclassified 2a. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY OF REPORT Approved for public release; 2b. DECLASSIFICATION/DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE distribution is unlimited 4. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) S. MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 6a. NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 6b.J OFFICE(i applicable) SYMBOL 7a. NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School 39 Naval Postgraduate School 6c. ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b. ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) Monterey, CA 93943-5000 Monterey, CA 93943-5000 8a. NAME OF FUNDING/SPONSORING 8b. OFFICE SYMBOL 9. PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ORGANIZATION (Ifapplicable) 8c. ADDRESS (City, State, andZIP Code) 10. SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS PROGRAM PROJECT TASK WORK UNIT ELEMENT NO. NO. NO. ACCESSION NO. 11. TITLE (Include Security Classification) The Israeli Defense Forces: An Organizational Perspective 12. PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) Matthew J. Green 13a. TYPE OF REPORT 13b. TIME COVERED 14. DATE OF REPORT (Year, Month, Day) 15. PAGE COUNT Master's Thesis IFROM TOI March 1990 155 16. -

Congressional Record—House H2447

March 13, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2447 every turn, we will never retreat, and we will I ask my colleagues to join me in supporting House Resolution 107, calling for the imme- prevail because the cause of freedom is just Israel and condemning these heinous acts, diate and unconditional release of the Israeli and righteous. As one of my heroes, President and cast a vote in favor of H. Res. 107. soldiers held captive by Hamas and Hezbollah John F. Kennedy, once said, ‘‘Let every nation Mr. GARRETT of New Jersey. Mr. Speaker, since last summer. know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we it’s been more than seven months now and The critical bipartisan legislation being intro- shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet many have forgotten about the three Israeli duced today calls for the immediate and un- any hardship, support any friend, oppose any soldiers kidnapped by Hamas and Hezbollah: conditional release of the three Israeli soldiers foe, in order to assure the survival and the Ehud Goldwasser, Eldad Regev, and Gilad who were captured last summer. Ehud success of liberty.’’ Today we renew this Shalit. Hezbollah seems to have forgotten that Goldwasser, 31, and Eldad Regev, 26, were pledge. last year’s hostilities ended only after there kidnapped by Hezbollah on July 12, 2006. This resolution also makes it clear that while were promises regarding the return of the Gilad Shalit was kidnapped by Hamas on we do not shrink from the fight against ter- Israeli men. This just goes to reinforce the fact June 25, 2006. -

Deterrence and Realism

The Evolution of Israeli Military Strategy: Asymmetry, Vulnerability, Pre-emption and Deterrence Gerald M. Steinberg We are a generation that settles the land and without the steel helmet and the cannon’s maw, we will not be able to plant a tree and build a home. Let us not be deterred from seeing the loathing that is inflaming and filling the lives of the hundreds of thousands of Arabs who live around us. Let us not avert our eyes lest our arms weaken. This is the fate of our generation. This is our life's choice - to be prepared and armed, strong and determined, lest the sword be stricken from our fist and our lives cut down. --Moshe Dayan's Eulogy for Roi Rutenberg (April 19, 1956)1 Overview When the nascent Israeli leadership met on May 14, 1948, in Tel Aviv to declare independence, the country was already being attacked by neighboring Arab armies. The clearly stated objective was to destroy the miniscule Jewish state, with its very vulnerable borders, before it could be established, using the apparently decisive Arab advantages in terms of territorial extent, armed forces, demography, and political influence. Israel overcame these hurdles in 1948 and in subsequent military confrontations, yet despite the development of formidable military capabilities, the inherent asymmetries and existential threats to the Jewish nation-state remain. Given this environment, Israel‟s survival has depended on the development of appropriate strategic and tactical responses. The period from 1948 to 1973 was characterized primarily by large scale confrontations with the armies of Egypt, Syria, 1 Iraq and Jordan in different combinations. -

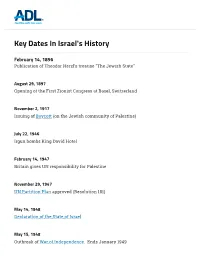

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution -

Hezbollah: a Localized Islamic Resistance Or Lebanon's Premier

Hezbollah: A localized Islamic resistance or Lebanon’s premier national movement? Andrew Dalack Class of 2010 Department of Near East Studies University of Michigan Introduction Lebanon’s 2009 parliamentary elections was a watershed moment in Lebanon’s history. After having suffered years of civil war, political unrest, and foreign occupation, Lebanon closed out the first decade of the 21st century having proved to itself and the rest of the world that it was capable of hosting fair and democratic elections. Although Lebanon’s political structure is inherently undemocratic because of its confessionalist nature, the fact that the March 8th and March 14th coalitions could civilly compete with each other following a brief but violent conflict in May of 2008 bore testament to Lebanon’s growth as a religiously pluralistic society. Since the end of Lebanon’s civil war, there have been few political movements in the Arab world, let alone Lebanon, that have matured and achieved as much as Hezbollah has since its foundation in 1985. The following thesis is a dissection of Hezbollah’s development from a localized militant organization in South Lebanon to a national political movement that not only represents the interests of many Lebanese, but also functions as the primary resistance to Israeli and American imperialism in Lebanon and throughout the broader Middle East. Particular attention is paid to the shifts in Hezbollah’s ideology, the consolidation of power and political clout through social services, and the language that Hezbollah uses to define itself. The sources I used are primarily secondhand; Joseph Alagha’s dissertation titled, The Shifts in Hizbullah’s Ideology: Religious Ideology, Political Ideology, and Political Program was one of the more significant references I used in substantiating my argument. -

Advance Edited Version Distr

Advance Edited Version Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/12/48 15 September 2009 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Twelfth session Agenda item 7 HUMAN RIGHTS IN PALESTINE AND OTHER OCCUPIED ARAB TERRITORIES Report of the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict∗ ∗ Late submission A/HRC/12/48 page 2 Paragraphs Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PART ONE INTRODUCTION I. METHODOLOGY II. CONTEXT III. EVENTS OCCURRING BETWEEN THE “CEASEFIRE” OF 18 JUNE 2008 BETWEEN ISRAEL AND THE GAZA AUTHORITIES AND THE START OF ISRAEL’S MILITARY OPERATIONS IN GAZA ON 27 DECEMBER 2008 IV. APPLICABLE LAW PART TWO OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY: THE GAZA STRIP Section A V. THE BLOCKADE: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW VI. OVERVIEW OF MILITARY OPERATIONS CONDUCTED BY ISRAEL IN GAZA BETWEEN 27 DECEMBER 2008 AND 18 JANUARY 2009 AND DATA ON CASUALTIES VII. ATTACKS ON GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS AND POLICE VIII. OBLIGATION ON PALESTINIAN ARMED GROUPS IN GAZA TO TAKE FEASIBLE PRECAUTIONS TO PROTECT THE CIVILIAN POPULATION A/HRC/12/48 page 3 IX. OBLIGATION ON ISRAEL TO TAKE FEASIBLE PRECAUTIONS TO PROTECT CIVILIAN POPULATION AND CIVILIAN OBECTS IN GAZA X. INDISCRIMINATE ATTACKS BY ISRAELI ARMED FORCES RESULTING IN THE LOSS OF LIFE AND INJURY TO CIVILIANS XI. DELIBERATE ATTACKS AGAINST THE CIVILIAN POPULATION XII. THE USE OF CERTAIN WEAPONS XIII. ATTACKS ON THE FOUNDATIONS OF CIVILIAN LIFE IN GAZA: DESTRUCTION OF INDUSTRIAL INFRASTRUCTURE, FOOD PRODUCTION, WATER INSTALLATIONS, SEWAGE TREATMENT PLANTS AND HOUSING XIV. THE USE OF PALESTINIAN CIVILIANS AS HUMAN SHIELDS XV. DEPRIVATION OF LIBERTY: GAZANS DETAINED DURING THE ISRAELI MILITARY OPERATIONS OF 27 DECEMBER 2008 TO 18 JANUARY 2009XVI.