Stephen Johnson Field: Near-Great Justice, Or Near-Greatest Justice?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Supremes on Religion: How Do the Justicesâ•Ž Religious Beliefs

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 2010 The uprS emes on Religion: How Do the Justices’ Religious Beliefs Influence their Legal Opinions? Leah R. Glasofer Seton Hall Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Glasofer, Leah R., "The uS premes on Religion: How Do the Justices’ Religious Beliefs Influence their Legal Opinions?" (2010). Law School Student Scholarship. 40. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/40 Leah R. Glasofer Law and Sexuality AWR Final Draft May 2, 2010 The Supremes on Religion: How Do the Justices’ Religious Beliefs Influence their Legal Opinions? This discussion is essentially an inquiry into the effect which religious beliefs have on the jurisprudence of the highest court of the land, the United States Supreme Court. With regard to actually creating laws, the Supreme Court wields an incredible amount of influence over the judiciary by way of precedent in federal courts, and persuasive authority in state courts. However, decisions by the most famed court in the country also mold and form the political and social climate of eras. Supreme Court decisions have defined our nation’s history, for example in US v. Nixon1 or Roe v. Wade.2 Thus, it seems worthwhile to explore the considerations taken into account by the Justices when they craft opinions which will inevitably shape the course of our national and personal histories. It is true that the religious beliefs of the people of the United States and their elected officials also play a leading role in the creation of laws which affect our lives; and people are entitled to be governed and live by the rules which they chose for society. -

The Role of Politics in Districting the Federal Circuit System

PUSHING BOUNDARIES: THE ROLE OF POLITICS IN DISTRICTING THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT SYSTEM Philip S. Bonforte† I. Introduction ........................................................................... 30 II. Background ............................................................................ 31 A. Judiciary Act of 1789 ......................................................... 31 B. The Midnight Judges Act ................................................... 33 C. Judiciary Act of 1802 ......................................................... 34 D. Judiciary Act of 1807 ....................................................... 344 E. Judiciary Act of 1837 ....................................................... 355 F. Tenth Circuit Act ................................................................ 37 G. Judicial Circuits Act ........................................................... 39 H. Tenth Circuit Act of 1929 .................................................. 40 I. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Reorganization Act of 1980 ...................................................... 42 J. The Ninth Circuit Dilemma ................................................ 44 III. The Role of Politics in Circuit Districting ............................. 47 A. The Presence of Politics ..................................................... 48 B. Political Correctness .......................................................... 50 IV. Conclusion ............................................................................. 52 † The author is a judicial clerk -

The Supreme Court, Segregation Legislation, and the African American Press, 1877-1920

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 Slipping Backwards: The Supreme Court, Segregation Legislation, and the African American Press, 1877-1920 Kathryn St.Clair Ellis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ellis, Kathryn St.Clair, "Slipping Backwards: The Supreme Court, Segregation Legislation, and the African American Press, 1877-1920. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kathryn St.Clair Ellis entitled "Slipping Backwards: The Supreme Court, Segregation Legislation, and the African American Press, 1877-1920." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. W. Bruce Wheeler, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Ernest Freeberg, Stephen V. Ash, -

60459NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov.1 1 ------------------------ 51st Edition 1 ,.' Register . ' '-"978 1 of the U.S. 1 Department 1 of Justice 1 and the 1 Federal 1 Courts 1 1 1 1 1 ...... 1 1 1 1 ~~: .~ 1 1 1 1 1 ~'(.:,.:: ........=w,~; ." ..........~ ...... ~ ,.... ........w .. ~=,~~~~~~~;;;;;;::;:;::::~~~~ ........... ·... w.,... ....... ........ .:::" "'~':~:':::::"::'«::"~'"""">X"10_'.. \" 1 1 1 .... 1 .:.: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 .:~.:.:. .'.,------ Register ~JLst~ition of the U.S. JL978 Department of Justice and the Federal Courts NCJRS AUG 2 1979 ACQlJ1SfTIOI\fS Issued by the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 'U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1978 51st Edition For sale by the Superintendent 01 Documents, U.S, Government Printing Office WBShlngton, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 027-ootl-00631Hl Contents Par' Page 1. PRINCIPAL OFFICERFI OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 1 II. ADMINISTRATIV.1ll OFFICE Ul"ITED STATES COURTS; FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 19 III. THE FEDERAL JUDICIARY; UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS AND MARSHALS. • • • • • • • 23 IV. FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTIONS 107 V. ApPENDIX • • • • • • • • • • • • • 113 Administrative Office of the United States Courts 21 Antitrust Division . 4 Associate Attorney General, Office of the 3 Attorney General, Office of the. 3 Bureau of Prisons . 17 Civil Division . 5 Civil Rights Division . 6 Community Relations Service 9 Courts of Appeals . 26 Court of Claims . '.' 33 Court of Customs and Patent Appeals 33 Criminal Division . 7 Customs Court. 33 Deputy Attorney General, Offico of. the 3 Distriot Courts, United States Attorneys and Marshals, by districts 34 Drug Enforcement Administration 10 Federal Bureau of Investigation 12 Federal Correctional Institutions 107 Federal Judicial Center • . -

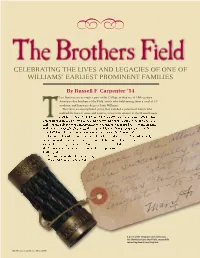

00339 Willams Pp32 BC.Indd

CELEBRATING THE LIVES AND LEGACIES OF ONE OF WILLIAMS’ EARLIEST PROMINENT FAMILIES By Russell F. Carpenter ’54 heir histories are as much a part of the College as they are of 19th-century America—fi ve brothers of the Field family who held among them a total of 10 academic and honorary degrees from Williams. They were an accomplished group that included a prominent lawyer who codifi ed the laws of states and nations, a four-term senator in the Massachusetts State Legislature and its president for three years, a U.S. Supreme Court justice, a minister who traveled the world speaking and writing about his experiences for a national audience and a fi nancier and entrepreneur who successfully connected America and England with the fi rst telegraph cable across the Atlantic. Many of their descendents also would attend Williams, including one today who is a member of the Class of 2008. The family planted its roots in America in 1632 with the arrival of Zechariah Field, who emigrated from England and settled outside Boston. Zechariah helped to found Hartford, Conn., in 1639 and 20 years later traveled up the Connecticut River Valley, settling in Northampton and Hatfi eld, Mass. Zechariah’s grandson Ebenezer, tiring of constant Indian raids on the A piece of the telegraph cable laid across the Atlantic by Cyrus West Field, successfully connecting America and England. 16 | WILLIAMS ALUMNI REVIEW | MARCH 2006 Six Field brothers in 1859 (from left): Henry Martyn, Cyrus West, Jonathan Edwards, David Dudley, Matthew Dickinson and Stephen Johnson. Siblings not pictured: Timothy Beals (lost at sea at age 27), Emilia MATTHEW BRADY (COURTESY OF TERRENCE SHEA) OF (COURTESY BRADY MATTHEW Ann and Mary Elizabeth. -

Protecting the Supreme Court: Why Safeguarding the Judiciary’S Independence Is Crucial to Maintaining Its Legitimacy

Protecting the Supreme Court: Why Safeguarding the Judiciary’s Independence is Crucial to Maintaining its Legitimacy Democracy and the Constitution Clinic Fordham University School of Law Isabella Abelite, Evelyn Michalos, & John Roque January 2021 Protecting the Supreme Court: Why Safeguarding the Judiciary’s Independence is Crucial to Maintaining its Legitimacy Democracy and the Constitution Clinic Fordham University School of Law Isabella Abelite, Evelyn Michalos, & John Roque January 2021 This report was researched and written during the 2019-2020 academic year by students in Fordham Law School’s Democracy and the Constitution Clinic, where students developed non-partisan recommendations to strengthen the nation’s institutions and its democracy. The clinic was supervised by Professor and Dean Emeritus John D. Feerick and Visiting Clinical Professor John Rogan. Acknowledgments: We are grateful to the individuals who generously took time to share their general views and knowledge with us: Roy E. Brownell, Esq., Professor James J. Brudney, Christopher Cuomo, Esq., Professor Bruce A. Green, and the Honorable Robert A. Katzmann. The report greatly benefited from Gail McDonald’s research guidance and Stephanie Salomon’s editing assistance. Judith Rew and Robert Yasharian designed the report. Table of Contents Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................1 Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................4 -

Judicial Politics

CHAPTER 7 Judicial Politics distribute or Photo 7.1 Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy swears in Neil Gorsuch as a new member of the Court while President Trump and Gorsuch’spost, wife, Louise, look on. oday politics lies squarely at the heart of the federal judicial selection Tprocess. That is nothing new, but partisan maneuvering in the Senate, which has the power to confirm or reject Supreme Court and lower federal court nominees put forward by the president, went to new extremes dur- ing the last year of the Obama administration and the opening months of the Trumpcopy, administration. The lengths to which the Republican-controlled Senate went to block the confirmation of Obama’s judicial nominees gave Trump the opportunity to appoint a backlog of judges when he took office. The most visible, and arguably the most audacious, obstruction came at the Supreme Court level when Justice Antonin Scalia, one of the Court’s notmost reliably conservative voters, died unexpectedly on February 13, 2016. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) almost immediately declared that the Republican-controlled Senate would not even consider any nominee put forward by President Obama. Retorting that the Senate had Do a constitutional duty to act on a nominee, Obama nonetheless nominated Merrick Garland, the centrist chief judge of the D.C. Circuit, on March 16, 401 Copyright ©2021 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. 2016. He did so with more than ten months left in his term—more than enough time to complete the confirmation process. -

The Supreme Court and Superman

THE SUPREME COURT AND SUPERMAN THE JUSTICES AND THE FAMOUS PEOPLE IN THEIR FAMILY TREES Stephen R. McAllister† HILE EXAMINING a photograph of the 1911 U.S. Supreme Court, I spotted Joseph Rucker Lamar, but was initially confused because I thought Justice Lamar served on the Court in the nineteenth century. I quickly discovered that Joseph was the cousin (distant, it turns out) of an earlier Justice, Lu- W 1 cius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II. I was aware of two other family rela- tionships between Justices who served on the Court: John Marshall Harlan and his grandson, John Marshall Harlan II, and Stephen Johnson Field and his nephew, David Josiah Brewer,2 with the service of only Field and Brewer overlapping.3 † Stephen McAllister is United States Attorney for the District of Kansas, and on leave of absence from the University of Kansas where he is the E.S. & Tom W. Hampton Distinguished Professor of Law. 1 His namesake presumably is Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the Roman farmer-statesman who legend holds was appointed dictator and left his farm in 458 B.C. to defend Rome against an attacking army, quickly defeated the enemy, and then immediately gave up his power and returned to his farm. 2 The Kansas Justice, David Josiah Brewer, 19 Green Bag 2d 37 (2015). 3 A particularly observant reader of the chart that accompanies this article, or a knowl- edgeable student of Supreme Court history, might wonder whether some other Justices 21 GREEN BAG 2D 219 Stephen R. McAllister Justice John Marshall Harlan, left (1833-1911) and right (1899-1971). -

Noah Haynes Swayne

Noah Haynes Swayne Noah Haynes Swayne (December 7, 1804 – June 8, 1884) was an Noah Haynes Swayne American jurist and politician. He was the first Republican appointed as a justice to the United States Supreme Court. Contents Birth and early life Supreme Court service Retirement, death and legacy See also Notes References Further reading Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States In office Birth and early life January 24, 1862 – January 24, 1881 Nominated by Abraham Lincoln Swayne was born in Frederick County, Virginia in the uppermost reaches of the Shenandoah Valley, approximately 100 miles (160 km) Preceded by John McLean northwest of Washington D.C. He was the youngest of nine children of Succeeded by Stanley Matthews [1] Joshua Swayne and Rebecca (Smith) Swayne. He was a descendant Personal details of Francis Swayne, who emigrated from England in 1710 and settled Born December 7, 1804 near Philadelphia.[2] After his father died in 1809, Noah was educated Frederick County, Virginia, U.S. locally until enrolling in Jacob Mendendhall's Academy in Waterford, Died June 8, 1884 (aged 79) Virginia, a respected Quaker school 1817-18. He began to study New York City, New York, U.S. medicine in Alexandria, Virginia, but abandoned this pursuit after his teacher Dr. George Thornton died in 1819. Despite his family having Political party Democratic (Before 1856) no money to support his continued education, he read law under John Republican (1856–1890) Scott and Francis Brooks in Warrenton, Virginia, and was admitted to Spouse(s) Sarah Swayne the Virginia Bar in 1823.[3] A devout Quaker (and to date the only Quaker to serve on the Supreme Court), Swayne was deeply opposed to slavery, and in 1824 he left Virginia for the free state of Ohio. -

Judicial Ghostwriting: Authorship on the Supreme Court Jeffrey S

Cornell Law Review Volume 96 Article 11 Issue 6 September 2011 Judicial Ghostwriting: Authorship on the Supreme Court Jeffrey S. Rosenthal Albert H. Yoon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey S. Rosenthal and Albert H. Yoon, Judicial Ghostwriting: Authorship on the Supreme Court, 96 Cornell L. Rev. 1307 (2011) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol96/iss6/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUDICIAL GHOSTWRITING: AUTHORSHIP ON THE SUPREME COURT Jeffrey S. Rosenthal & Albert H. Yoont Supreme Court justices, unlike the President or members of Congress, perfom their work with relatively little staffing. Each justice processes the docket, hears cases, and writes opinions with the assistanceof only their law clerks. The relationship between justices and their clerks is of intense interest to legal scholars and the public, but it remains largely unknown. This Arti- cle analyzes the text of the Justices' opinions to better understand judicial authorship. Based on the use of common function words, we find thatJus- tices vary in writing style, from which it is possible to accurately distinguish one from another. Their writing styles also inform how clerks influence the opinion-writingprocess. CurrentJustices, with few exceptions, exhibit signif- icantly higher variability in their writing than their predecessors, both within and across years. -

Lightsmonday, out February 10, 2020 Photo by Teresa Mettela 50¢ 57,000 Queensqueensqueens Residents Lose Power Volumevolume 65, 65, No

VolumeVol.Volume 66, No. 65,65, 80 No.No. 207207 MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARYFEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10,10, 2020 20202020 50¢ A tree fell across wires in Queens Village, knocking out power and upending a chunk of sidewalk. VolumeQUEENSQUEENS 65, No. 207 LIGHTSMONDAY, OUT FEBRUARY 10, 2020 Photo by Teresa Mettela 50¢ 57,000 QueensQueensQueens residents lose power VolumeVolume 65, 65, No. No. 207 207 MONDAY,MONDAY, FEBRUARY FEBRUARY 10, 10, 2020 2020 50¢50¢ VolumeVol.VolumeVol.VolumeVol. 66, 66,66, No.65, No. No.65,65, 80No. 80 80128No.No. 207 207207 MONDAY,THURSDAY,MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARY FEBRUARYFEBRUARYFEBRUARY AUGUSTOCTOBER AUGUSTAUGUST 6,10, 6,10,6,15,10, 10,2020 20202020 20202020 50¢50¢50¢ Volume 65, No. 207 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2020 50¢ VolumeVol.TODAY 66, No.65, 80No. 207 MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10, 2020 2020 A tree fell across wires in50¢ TODAY AA tree tree fell fell across across wires wires in in TODAY QueensQueensQueens Village, Village, Village, knocking knocking knocking Tomorrow is outoutout power power power and and and upending upending upending A treeaa chunka chunkfell chunk across of of ofsidewalk. sidewalk. sidewalk.wires in VolumeVolumeVolumeQUEENSQUEENSQUEENSQUEENS 65, 65,65, No. No.No. 207 207207 LIGHTSLIGHTSduring intenseMONDAY,MONDAY, OUTOUTOUT FEBRUARY FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 10, 10,10, 2020 20202020 QueensPhotoPhoto PhotoVillage, by by byTeresa Teresa Teresa knocking Mettela Mettela Mettela 50¢50¢50¢ QUEENS the lastout power and day upending 57,00057,000 Queens QueensQueensQueensQueensQueens a chunk -

The California Judiciary

UC Berkeley California Journal of Politics and Policy Title The California Judiciary Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6cx5w2qr Journal California Journal of Politics and Policy, 7(4) Authors Carrillo, David A Duvernay, Stephen M. Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/P2cjpp7429126 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The California Judiciary David A. Carrillo School of Law, University of California, Berkeley Stephen M. Duvernay School of Law, University of California, Berkeley Introduction The California judiciary is one of the three constitutional branches of the state government. This paper provides an overview of the current state court system, its historical development, its relationship with the other branches of state government and the federal courts, and a comparison of California’s judiciary with other states’ judicial systems. Why study state courts? While the federal courts can at times have a higher profile, the courts of the 50 states vastly outnumber their federal colleagues. Combined, the state high courts decide over ten thousand cases each year, far more than the federal courts, and in many of those cases the Supreme Court of the United States either declines to hear requests to review them, or has no jurisdiction to do so.1 As a result, the state courts arguably have an overall greater effect on American jurisprudence and an even greater effect on the citizens of their respective states. Due to the diversity among the state judicial systems, and their distinct differences from the federal high court, there is neither a typical state high court nor a typical role for those courts in the state and national arenas.2 Consequently, studying the federal judiciary does not lead to a good understanding of the state courts.