Fragmented Citizenship in a Fragmented State: Ideas, Institutions, and the Failure of Reconstruction Allen C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

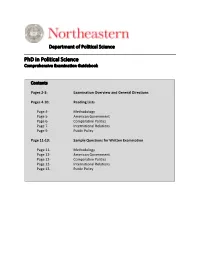

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

US Racial Politics II New Deal to the Present

U.S. Racial Politics: New Deal to the Present Political Science 449/549 CRN: 37625 Professor: Joseph Lowndes Office: PLC 919 email: [email protected] Graduate Employee: Course description: In this course, we will examine the ways that race shaped the major political dynamics in the United States from the Great Depression to the present. Materials: There are two books for this course, available in the bookstore. The books are The Unsteady March, by Philip Klinkner and Rogers Smith; and When Affirmative Action Was White, by Ira Katznelson. PS 5549 will have one additional text: Lowndes, Novkov and Warren, eds. Race and American Political Development. All other readings will be available on Canvas. Requirements for 449: This is a heavy reading course 1. Seven in-class quizzes. These quizzes will assess your comprehension of the assigned reading, lectures and class discussions. Your lowest two scores will be dropped. No make-up quizzes are possible. (50% of final grade) 2. Midterm in-class exam (25% of final grade) 3. Final exam (25% of final grade) 4. Participation: Students will be expected to attend class and participate in class discussions. Constructive, informed, respectful participation that contributes directly to conversations about the course material will raise borderline grades; lack of participation may result in lower grades. Requirements for 549: Research paper 18-20 pages, due Wednesday of Finals Week. Meet with me by 4th week with thesis topic to discuss. Policies: Students with disabilities. If you have a documented disability and anticipate needing accommodations in this course, please make arrangements to meet with the professor soon. -

Introduction to American Political Culture

Bellevue College INTRODUCTION TO AMERICAN POLITICAL CULTURE Political Science 160/Cultural & Ethnic Studies 160 Item 5361 A (POLS 160) or 5638 (CES 160) (Five Credits)1 Winter 2011 (Jan. 3-March 22), 11:30 a.m.-12:20 p.m. (L-221) Dr. T. M. Tate (425) 564-2169 [email protected] Office: D-200C Office Hours: See MyBC course site Pre-requisite: None Course Description This course treats the ways in which American cultural patterns influence and shape political outcomes and public policy. Study of the political culture may shed light on the nature of the political struggles and on the policy process in general. Political outcomes in the United States are not random but are structured and connected by certain enduring values. We seek answers to questions such as: How do Americans thinks about government, political institutions, social welfare, and the market? What are the origins and sources of American political culture? How has it changed over time, and what factors account for this change? How is American political culture distinctive, and how is it being reshaped in a time of globalization? In the process of this broad inquiry, we necessarily treat concepts such as democracy, liberty, individualism, American “exceptionalism,” political community, and political culture itself. Learning Outcomes On completion of this course, you should be able to: Explain the concept of political culture and its relevance to contemporary political society. 1 One credit hour of this course is online via MyBC. Identify the core values in American political culture and understand their influences on political life. Demonstrate how the political culture influences and shapes American politics and the policy process. -

Citizenship Denationalized (The State of Citizenship Symposium)

Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 7 Issue 2 Article 2 Spring 2000 Citizenship Denationalized (The State of Citizenship Symposium) Linda Bosniak Rutgers Law School-Camden Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Bosniak, Linda (2000) "Citizenship Denationalized (The State of Citizenship Symposium)," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol7/iss2/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Citizenship Denationalized LINDA BOSNIAK° INTRODUCTION When Martha Nussbaum declared herself a "citizen of the world" in a recent essay, the response by two dozen prominent intellectuals was overwhelmingly critical.' Nussbaum's respondents had a variety of complaints, but central among them was the charge that the very notion of world citizenship is incoherent. For citizenship requires a formal governing polity, her critics asserted, and clearly no such institution exists at the world level. Short of the establishment of interplanetary relations, a world government is unlikely to take form anytime soon. A good thing too, they added, since such a regime would surely be a tyrannical nightmare.2 * Professor of Law, Rutgers Law School-Camden; B.A., Wesleyan University; M.A., University of California, Berkeley; J.D., Stanford University. -

The Role of Politics in Districting the Federal Circuit System

PUSHING BOUNDARIES: THE ROLE OF POLITICS IN DISTRICTING THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT SYSTEM Philip S. Bonforte† I. Introduction ........................................................................... 30 II. Background ............................................................................ 31 A. Judiciary Act of 1789 ......................................................... 31 B. The Midnight Judges Act ................................................... 33 C. Judiciary Act of 1802 ......................................................... 34 D. Judiciary Act of 1807 ....................................................... 344 E. Judiciary Act of 1837 ....................................................... 355 F. Tenth Circuit Act ................................................................ 37 G. Judicial Circuits Act ........................................................... 39 H. Tenth Circuit Act of 1929 .................................................. 40 I. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Reorganization Act of 1980 ...................................................... 42 J. The Ninth Circuit Dilemma ................................................ 44 III. The Role of Politics in Circuit Districting ............................. 47 A. The Presence of Politics ..................................................... 48 B. Political Correctness .......................................................... 50 IV. Conclusion ............................................................................. 52 † The author is a judicial clerk -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics of Social Solidarity

Kathleen Thelen Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics XXI (73) - 2015 of Social Solidarity 2014. Cambridge University Press. Pages: 251 ISBN: 9781107679566 Are notions of solidarity obsolete in the face of the free market? Is there a single developed capitalism or are there many? Is there a best, most efficient way to delimit the state from the market and the public from the private or are there alternative, equally efficient solutions? Comparative political economy is often based on the premise that the latter is true. In particular, the now classic Varieties of Capitalism (VofC) comparative approach postulates two types of institutional frameworks. The general idea was that each institutional solution generates positive externalities which may or may not be captured by specific solutions in other institutional domains. Therefore, the precondition for economic success of any given country is not any single institutional solution, but rather a consistent approach throughout the political economy cutting through finance, labor markets, education, inter-firm relations etc. The analysis of developed countries revealed two principal types of such institutional consistency – the coordinated market economy (CME) as a more restrictively regulated variety of capitalism and the liberal market economy (LME) as a more flexible variety oriented towards free markets. The CME path to efficiency and growth is based on the formation of specific skills, protected and organized labor markets and long-term bank-centric corporate governance systems. This was considered as an approach of the Scandinavian countries, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Japan. On the other hand, LME countries base their institutional comparative advantage on general skill formation, flexible labor markets with low unionization and short-term oriented corporate governance with predominant stock-market financing. -

Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism and Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change* by Vivien A

Center for European Studies Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper Series 07.3 (2007) Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism * And Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change by Vivien A. Schmidt Jean Monnet Professor of European Integration Department of International Relations, Boston University 152 Bay State Road, Boston MA 02215 Tel: 1 617 3580192; Fax: 1 617 3539290 Email: [email protected] Abstract The Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) literature’s difficulties in accounting for the full diversity of na- tional capitalisms and in explaining institutional change result at least in part from its tendency to downplay state action and from its rather static, binary division of capitalism into two overall systems. This paper argues first of all that by taking state action—used as shorthand for govern- ment policy forged by the political interactions of public and private actors in given institutional contexts—as a significant factor, national capitalisms can be seen to come in at least three varie- ties: liberal, coordinated, and state-influenced market economies. But more importantly, by bring- ing the state back in, we also put the political back into political economy—in terms of policies, political institutional structures, and politics. Secondly, the paper shows that although recent re- visions to VoC that account for change by invoking open systems or historical institutionalist in- *Paper prepared for presentation for the panel: 7-5 “Explaining institutional change in different varieties of capitalism,” of the Annual Meetings of the American Political Science Association (Philadelphia PA, Aug. 31-Sept. 3, 2006). -

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT and Permanent External Scientific Member, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, Germany Address Department of Political Science [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology http://web.mit.edu/polisci/faculty/K.Thelen.html 77 Massachusetts Avenue, E53-470 Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 Education M.A. (1981) and Ph.D. (1987), Political Science, University of California, Berkeley B.A. (1979), Political Science, University of Kansas (university and department honors) Teaching Positions Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT (2009-present) Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2005-2009) Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2004-2005) Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University (1994-2004) Assistant Professor, Department of Politics, Princeton University, 1988-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Oberlin College, 1987-1988 Other Appointments and Invited Visiting Positions 2012- 2014 Research Fellow, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung April 2013: Guest scholar, Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden Summer 2011: Guest scholar, Institute for Advanced Study Berlin (Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin) and Science Center (Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung) Summer 2010: Visiting Professor, Sciences Po, Paris 2007-2011: Senior Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford University, Oxford UK -

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Oxford Handbooks Online Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Julia Lynch and Martin Rhodes The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism Edited by Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia G. Falleti, and Adam Sheingate Print Publication Date: Mar 2016 Subject: Political Science, Comparative Politics, Political Institutions Online Publication Date: May 2016 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199662814.013.25 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines how historical institutionalism has influenced the analysis of welfare state and labor market policies in the rich industrial democracies. Using Lakatos’s concept of the “scientific research program” as a heuristic, the authors explore the development and expansion of historical institutionalism as a predominant approach in welfare state research. Focusing on this tradition’s strong core of actors (academic path- and boundary-setters), rules (methodology and methods), and norms (ontological and epistemological assumptions), they strive to demarcate the terrain of HI within studies of the welfare state, and to reveal the capacity of HI in this field to underpin a robust but flexible and enduring scholarly research program. Keywords: welfare state, Lakatos, research program, historical institutionalism, ideational approaches HISTORICAL institutionalism and the analysis of welfare states (including the ancillary policy domain of the labor market) overlap significantly. More than elsewhere in Political Science and public policy, much single-country, program, and comparative analysis of the welfare state since the 1980s has taken an historical approach (Amenta 2003). Relatedly, some of the major welfare state scholars have also been major historical institutionalism theorists and proponents—most prominently, but not only, Theda Skocpol, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen. -

American Political Science Review

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW AMERICAN https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000060 . POLITICAL SCIENCE https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms REVIEW , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at 08 Oct 2021 at 13:45:36 , on May 2018, Volume 112, Issue 2 112, Volume May 2018, University of Athens . May 2018 Volume 112, Issue 2 Cambridge Core For further information about this journal https://www.cambridge.org/core ISSN: 0003-0554 please go to the journal website at: cambridge.org/apsr Downloaded from 00030554_112-2.indd 1 21/03/18 7:36 AM LEAD EDITOR Jennifer Gandhi Andreas Schedler Thomas König Emory University Centro de Investigación y Docencia University of Mannheim, Germany Claudine Gay Económicas, Mexico Harvard University Frank Schimmelfennig ASSOCIATE EDITORS John Gerring ETH Zürich, Switzerland Kenneth Benoit University of Texas, Austin Carsten Q. Schneider London School of Economics Sona N. Golder Central European University, and Political Science Pennsylvania State University Budapest, Hungary Thomas Bräuninger Ruth W. Grant Sanjay Seth University of Mannheim Duke University Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Sabine Carey Julia Gray Carl K. Y. Shaw University of Mannheim University of Pennsylvania Academia Sinica, Taiwan Leigh Jenco Mary Alice Haddad Betsy Sinclair London School of Economics Wesleyan University Washington University in St. Louis and Political Science Peter A. Hall Beth A. Simmons Benjamin Lauderdale Harvard University University of Pennsylvania London School of Economics Mary Hawkesworth Dan Slater and Political Science Rutgers University University of Chicago Ingo Rohlfi ng Gretchen Helmke Rune Slothuus University of Cologne University of Rochester Aarhus University, Denmark D. -

Solidarity and the Promo

16 inequality and solidarity iwmpost continued from page 13 cio-economic inequality, the Euro- access to power, or does it take the peans looked to their governments Commemoration agency of the disadvantaged them- and the EU for redistributive poli- Ceremony selves? Katherine Newman’s analysis cies. As Claus Offe remarked: “We of the effects of taxation in the US can legislate standards for clean air; On the first evening of the con- Solidarity and the Promotion of Good Life below the federal level demonstrat- why does it not seem possible to leg- ference, a commemoration ceremony ed how state actions can create, or islate for lower Gini coefficients?” ◁ in memoriam Krzysztof Michalski at least exacerbate, inequality. Alfred 1) OECD: Divided We Stand. Why (1948–2013), founding Rector of Gusenbauer pointed out in his con- Inequality Keeps Rising, 2011. the IWM, took place at the Museum report 2) of Applied Arts Vienna. In his cluding remarks that, furthermore, Congressional Budget Office: Trends in the Distribution of Household Income between memory, Michael Sandel, Anne T. people are much more critical of the 1979 and 2007, 2011. and Robert M. Bass Professor of The economic downturn and the rigorous austerity Government at Harvard University inequalities created by the state than 3) Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett: and member of the IWM Academic policies that followed the banking and financial crisis of those created by the markets. How- The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, Bloomsbury Press: Advisory Board, gave a lecture on ever, in their suggested solutions, London, 2009.