A Leap of Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

Guardian and Observer Editorial

Monday 01.01.07 Monday The year that changed our lives Swinging with Tony and Cherie Are you a malingerer? Television and radio 12A Shortcuts G2 01.01.07 The world may be coming to an end, but it’s not all bad news . The question First Person Are you really special he news just before Army has opened prospects of a too sick to work? The events that made Christmas that the settlement of a war that has 2006 unforgettable for . end of the world is caused more than 2 million people nigh was not, on the in the north of the country to fl ee. Or — and try to be honest here 4 Carl Carter, who met a surface, an edify- — have you just got “party fl u”? ing way to conclude the year. • Exploitative forms of labour are According to the Institute of Pay- wonderful woman, just Admittedly, we’ve got 5bn years under attack: former camel jockeys roll Professionals, whose mem- before she flew to the before the sun fi rst explodes in the United Arab Emirates are to bers have to calculate employees’ Are the Gibbs watching? . other side of the world and then implodes, sucking the be compensated to the tune of sick pay, December 27 — the fi rst a new year’s kiss for Cherie earth into oblivion, but new year $9m, and Calcutta has banned day back at work after Christmas 7 Karina Kelly, 5,000,002,007 promises to be rickshaw pullers. That just leaves — and January 2 are the top days 16 and pregnant bleak. -

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

NATO Accession Debate in Sweden and Finland, 1991-2016 Boldyreva, Slavyana Yu.; Boldyrev, Roman Yu.; Ragozin, G

www.ssoar.info A 'Secret alliance' or 'Freedom from any alliances'? NATO accession debate in Sweden and Finland, 1991-2016 Boldyreva, Slavyana Yu.; Boldyrev, Roman Yu.; Ragozin, G. S. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Boldyreva, S. Y., Boldyrev, R. Y., & Ragozin, G. S. (2020). A 'Secret alliance' or 'Freedom from any alliances'? NATO accession debate in Sweden and Finland, 1991-2016. Baltic Region, 12(3), 23-39. https:// doi.org/10.5922/2079-8555-2020-2-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-70194-6 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A ‘SECRET ALLIANCE’ OR ‘FREEDOM FROM ANY ALLIANCES’? NATO ACCESSION DEBATE IN SWEDEN AND FINLAND, 1991—2016 S. Yu. Boldyreva R. Yu. Boldyrev G. S. Ragozin Northern Arctic Federal University named after M. V. Lomonosov Received 25 August 2019 17 Severnaya Dvina Emb., Arkhangelsk, Russia, 163002 doi: 10.5922/2079-8555-2020-2-2 © Boldyreva S. Yu., Boldyrev R. Yu., Ragozin G. S., 2020 The authors analyze the NATO relations with Sweden and Finland, the neutral states of Northern Europe, in 1991—2016. The authors emphasize that Finland and Sweden have always been of high strategic importance for NATO and the EU defence policy. -

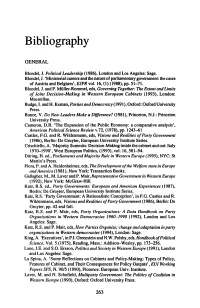

Bibliography

Bibliography GENERAL Blonde!, J. Political Leadership (1986), London and Los Angeles: Sage. Blonde!, J. 'Ministerial careers and the nature of parliamentary government: the cases of Austria and Belgium', EJPR vol. 16, (l) (1988), pp. 51-71. Blonde!, J. and F. MUller-Rommel, eds, Governing Together: Tile Extent and Limits of Joint Decision-Making in Western European Cabinets (1993), London: Macmillan. Budge, I. and H. Kernan, Parties and Democracy ( 1991 ), Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bunce, V. Do New Leaders Make a Difference? (1981), Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Cameron, D.R. 'The Expansion of the Public Economy: a comparative analysis', American Political Science Review v.12, (1978), pp. 1243-61 Castles, P.O. and R. Wilden mann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Criscitiello, A. 'Majority Summits: Decision-Making inside the cabinet and out: Italy 1970-1990', West European Politics, (1993), vol. 16, 581-94. Dt>ring, H. ed., Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe (1995), NYC: St Martin's Press. Flora, P. and A. Heidenheimer, eds, The Development ofthe Welfare state in Europe and America (1981), New York: Transaction Books. Gallagher, M., M. Laver and P. Mair, Representative Government in Western Europe (1992), New York: McGraw-Hill. Katz, R.S. ed., Party Govemments: European and American Expe1·iences (1987), Berlin: De Gruyter, European University Institute Series. Katz, R.S. 'Party Government: A Rationalistic Conception', in F. G. Castles and R. Wildenmann, eds, Visions and Realities of Party Government (1986), Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 42 and foil. Katz, R.S. -

30 March 2012 Page 1 of 17

Radio 4 Listings for 24 – 30 March 2012 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 24 MARCH 2012 SAT 06:57 Weather (b01dc94s) The Scotland Bill is currently progressing through the House of The latest weather forecast. Lords, but is it going to stop independence in its tracks? Lord SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b01dc948) Forsyth Conservative says it's unlikely Liberal Democrat Lord The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Steel thinks it will. Followed by Weather. SAT 07:00 Today (b01dtd56) With John Humphrys and James Naughtie. Including Yesterday The Editor is Marie Jessel in Parliament, Sports Desk, Weather and Thought for the Day. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b01dnn41) Tim Winton: Land's Edge - A Coastal Memoir SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (b01dtd5j) SAT 09:00 Saturday Live (b01dtd58) Afghans enjoy New Year celebrations but Lyse Doucet finds Episode 5 Mark Miodownik, Luke Wright, literacy champion Sue they are concerned about what the months ahead may bring Chapman, saved by a Labradoodle, Chas Hodges Daytrip, Sarah by Tim Winton. Millican John James travels to the west African state of Guinea-Bissau and finds unexpected charms amidst its shadows In a specially-commissioned coda, the acclaimed author Richard Coles with materials scientist Professor Mark describes how the increasingly threatened and fragile marine Miodownik, poet Luke Wright, Sue Chapman who learned to The Burmese are finding out that recent reforms in their ecology has turned him into an environmental campaigner in read and write in her sixties, Maurice Holder whose life was country have encouraged tourists to return. -

Dcrsc Food Programme Newsletter for April 2006

DEVON & CORNWALL REFUGEE SUPPORT A Private Company Limited by Guarantee Providing Practical Support To NEWSLETTER Refugees JULY 2010 7 Whimple Street, Plymouth PL1 2DH Tel: 01752 265952 Fax: 0870 762 6228 Email: [email protected] Website: http://dcrsc1.cfsites.org FOREWORD Yours sincerely Written by Lorna M. SEWELL Lorna M. Sewell Dear Friends and Supporters, Lorna M. SEWELL Chair of the DCRS Board of Trustees As you may be aware we experimented with our Annual General Meeting this year, and instead of organising a big affair in Sherwell’s Church Hall, as we have done for a number of years, the Trustees decided to hold an CONTENTS Open Day followed by our AGM, during Refugee Week Compiled by Geoffrey N. READ and on home ground. We had a few reservations about this for a number of reasons, not least the space Just run your mouse over the blue links and click... you’ll be taken straight to your page! available, but from all accounts it proved to be quite successful. If there were complaints, they haven’t Activities Group Page 4 reached me! Advertisements Page 7 Although it was a much smaller event, it still had to be Clothing Store Page 5 organised, as these events don’t organise themselves, so Diary Dates Page 21 I would like to thank all those involved. General Information Page 3 At the AGM, we took the opportunity of welcoming our Editorial Comment Page 1 new auditor who had spent some time making sure our Food Programme Page 5 finances were in good order for 2009, and he was Foreword Page 1 elected for the coming year. -

The Olof Palme International Center

About The Olof Palme International Center The Olof Palme International Center works with international development co-operation and the forming of public opinion surrounding international political and security issues. The Palme Center was established in 1992 by the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Trade Union Confederation (LO) and the Cooperative Union (KF). Today the Palme Center has 28 member organizations within the labour movement. The centre works in the spirit of the late Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, reflected by the famous quotation: "Politics is wanting something. Social Democratic politics is wanting change." Olof Palme's conviction that common security is created by co-operation and solidarity across borders, permeates the centre's activities. The centre's board is chaired by Lena Hjelm-Wallén, former foreign minister of Sweden. Viola Furubjelke is the centre's Secretary General, and Birgitta Silén is head of development aid. There are 13 members of the board, representing member organisations. The commitment of these member organisations is the core of the centre's activities. Besides the founding organisations, they include the Workers' Educational Association, the tenants' movement, and individual trade unions. As popular movements and voluntary organisations , they are represented in all Swedish municipalities and at many workplaces. An individual cannot be a member of the Palme Center, but the member organisations together have more than three million members. In Sweden, the centre carries out comprehensive information and opinion-forming campaigns on issues concerning international development, security and international relations. This includes a very active schedule of seminars and publications, both printed and an e-mail newsletter. -

For Submission

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE COPYRIGHT NOTICE The copyright of this research report vests in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, in accordance with the University’s Intellectual Property Policy. No portion of the text may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including analogue and digital media, without prior written permission from the University. Extracts of or quotations from this research report may, however, be made in terms of Section 12 and 13 of the South African Copyright Act of No. 98 of 1978 (as amended), for non-commercial or educational purposes. Full acknowledgement must be made to the author and the University. An electronic version of this research report is available on the Library webpage (www.wits.ac.za/library ) under “Research Resources”. For permission requests, please contact the University Legal Office or the University Research Office (www. wits.ac.za). i AN EXAMINATION OF SCHOOL FEEDING PROGRAMMES AS INCLUSIVE STRATEGIES Sibili Precious Nsibande Student No: 909874 Supervisor: Dr Yasmine Dominguez-Whitehead A research project submitted to the WITS School of Education, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education by combination of coursework and research Johannesburg, 2016 ii ABSTRACT In an attempt to promote inclusive education, many schools have put strategies in place to ensure that all children access and participate in learning. An inclusive strategy is defined as a practice or something that people do to give meaning to the concept of inclusion (Florian, 2011). -

(American Swedish News Exchange, New York, NY), 1920S-1990

Allan Kastrup collection (American Swedish News Exchange, New York, N.Y), 1920s-1990 Size: 19.25 linear feet, 28 boxes Acquisition: The collection was donated to SSIRC in 1990 and 1991. Access: The collection is open for research and a limited amount to copies can be requested via mail. Processed by: Christina Johansson Control Num.: SSIRC MSS P: 308 Historical Sketch The American-Swedish News Exchange was established by the Sweden-America Foundation in Stockholm in 1921 and the agency opened its office in New York City in 1922. ASNE's main purpose was to increase and broaden the general knowledge about Sweden and to provide the American press with news on cultural, economic and political developments in Sweden. The agency also had the primary responsibility for publicity campaigns during Swedish official visits to the United States, such as the Crown Prince Gustav Adolf's visit in 1926, the New Sweden Tercentenary in 1938, and the Swedish Pioneer Centennial in 1948. Between 1926 and 1946, ASNE was under the leadership of Naboth Hedin. Hedin increased the visibility of Sweden in the American press immensely, wrote countless of articles on Sweden, and co-edited with Adolph H. Benson Swedes in America: 1638-1938. Hedin was also instrumental in assisting many American writers with advice and information about Sweden; including Marquis W. Childs in his widely read and circulated work Sweden the Middle Way, first published in 1936. Allan Kastrup assumed the leadership of ASNE in 1946. He held this position until his retirement in 1964, at which time ASNE ceased to exist and its responsibilities were assumed by the Swedish Information Service. -

Annual Report 2001

Sveriges Riksbank A R Contents INTRODUCTION SVERIGES RIKSBANK 2 2001 IN BRIEF 3 STATEMENT BY THE GOVERNOR 4 OPERATIONS 2001 MONETARY POLICY 7 FINANCIAL STABILITY 13 INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION 16 STATISTICS 18 RESEARCH 19 THE RIKSBANK’S SUBSIDIARIES 20 THE RIKSBANK’S PRIZE IN ECONOMIC SCIENCES 22 SUBMISSIONS 23 HOW THE RIKSBANK WORKS THE MONETARY POLICY PROCESS 25 THE ANALYSIS OF FINANCIAL STABILITY 29 MANAGEMENT AND ORGANISATION ORGANISATION 32 THE EXECUTIVE BOARD 34 EMPLOYEES 36 IMPORTANT DATES 2002 Executive Board monetary policy meeting 7 February THE GENERAL COUNCIL 38 Executive Board monetary policy meeting 18 March Inflation Report no. 1 published 19 March ANNUAL ACCOUNTS The Governor attends the Riksdag Finance Committee hearing 19 March Executive Board monetary policy meeting 25 April DIRECTORS’ REPORT 40 Executive Board monetary policy meeting 5 June Inflation Report no. 2 published 6 June ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES 43 Executive Board monetary policy meeting 4 July Executive Board monetary policy meeting 15 August BALANCE SHEET 44 The dates for the monetary policy meetings in the autumn have not yet been con- PROFIT AND LOSS ACCOUNT 45 firmed. Information on monetary policy decisions is usually published on the day following a monetary policy meeting. NOTES 46 THIS YEAR’S PHOTOGRAPHIC THEME FIVE-YEAR OVERVIEW 50 Sveriges Riksbank is a knowledge organisation and the bank aims to achieve a learning climate that stimulates and develops employees. Employees can acquire SUBSIDIARIES 51 knowledge both through training and in working together with colleagues and ex- ternal contacts. The Riksbank’s independent position requires openness with re- ALLOCATION OF PROFITS 53 gard to the motives behind its decisions. -

MED MIGRANTERNAS RÖST Den Subjektiva Integrationen Bi Puranen

Forskningsrapport 2019/2 MED MIGRANTERNAS RÖST Den subjektiva integrationen Bi Puranen MED MIGRANTERNAS RÖST Den subjektiva integrationen 1 Forskningsrapport 2019/2 MED MIGRANTERNAS RÖST Den subjektiva integrationen Bi Puranen Institutet för Framtidsstudier är en självständig forskningsstiftelse finansierad genom bidrag från statsbudgeten och via externa forskningsanslag. Institutet bedriver tvärvetenskaplig forskning kring framtidsfrågor och verkar för en offentlig framtidsdebatt genom bland annat publikationer, seminarier och konferenser. © Författarna och Institutet för Framtidsstudier 2019 ISBN: 978-91-978537-8-1 Layout inlaga: Matilda Svensson Tryck: Elanders, 2019 Foto: s. 234, Sanar Alsammarraie; s. 258, Krister Lönn; s. 259, Johan Eklund. Övriga porträttfotografier på omslag och i rapporten är tagna av mWWS:s intervjuteam. Distribution: Institutet för Framtidsstudier 4 INNEHÅLL Figur- och tabellförteckning 7 Sammanfattning 13 Summary 18 Förord 23 1. Inledning 24 1.1 Bakgrund 25 1.2. World Values Survey 27 1.3 Migranternas röst 31 1.4. Från assimilation över mångkultur till tvåvägsintegration 34 1.5. Sysselsättningsgapet och värderingarna 46 1.6 Migrationsbegreppet idag 48 2. Teoretisk bakgrund 54 2.1. Värderingar och sociala normer 55 2.2. Hur förändras värderingar i samband med migration? 57 2.3. Frågeställningar 61 3. Studiens struktur – en deskriptiv redovisning 68 3.1 Vilka migranter ingår? 69 3.2. Tre urvalsmetoder 70 3.3. Ursprungsland och tid i Sverige 76 3.4. Medborgarskap och typ av uppehållstillstånd 79 3.5. Ett mini-Sverige 84 3.5. SFI och gymnasiets ”svenska för nyanlända” 86 3.7. Intervjudata 96 3.8. Forskningsetiska överväganden 99 3.9. Hur genomfördes studien? 99 4. Varför Sverige? 102 4.1. Inledning 103 4.2.