The University of New South Wales Thesis/Dissertation Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Natural History of Upper Sturt, South Australia Part I

THE NATURAL HISTORY OF UPPER STURT, SOUTH AUSTRALIA PART I: VEGETATION HISTORY, FLORA AND MACROFUNGI OF A MESSMATE STRINGYBARK FOREST Tony Robinson and Julia Haska PO Box 47 UPPER STURT SA 5156 Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: An area of Eucalyptus obliqua, Messmate Stringybark Forest in Upper Sturt, Mt Lofty Ranges, South Australia was studied over a 38 year period. The land use history since the area was first settled by Europeans in 1843, to the present day is summarized. The area is now known to support 249 species of plants of which 105 species are introduced and 64 species of macrofungi of which at least 3 are introduced. Although the area has undergone many changes since European settlement it remains an important area of remnant native vegetation. There are ongoing challenges from weed invasion, overgrazing by over-abundant kangaroos and introduced koalas and from potential damage by severe wildfire KEY WORDS: Upper Sturt, land use history, forest, flora, fungi, vegetation INTRODUCTION: This is the first of three papers describing revegetation of cleared land adjacent to areas of relatively natural remnant native vegetation. In this paper, elements of the vegetation, flora and fungi are described in a study area at 16 Pole Road, Upper Sturt in the Mt Lofty Ranges. The second paper describes the vertebrate and invertebrate fauna of the area, while the third paper provides results of fauna and vegetation monitoring in sample sites established in both the re-vegetated area and the remnant natural vegetation in the Upper Sturt study area. A second series of three papers will cover the flora and fauna and a more extensive revegetation program on a study area on the western end of Kangaroo Island (in prep.). -

Pacific Communities in Australia

PACIFIC COMMUNITIES IN AUSTRALIA JIOJI RAVULO SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & PSYCHOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY Acknowledgements Many thanks to Mary Moeono-Kolio for writing support and drafting assistance, Losana Ravulo for continuous feedback on scope of report, and the Pasifika Achievement To Higher Education (PATHE) team for supporting the vision of Pasifika development across Australia and beyond. Statistics cited within this report is from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Census of Population and Housing 2011. Appreciation is expressed for the assistance provided by the ABS Microdata Access Strategies Team. © Jioji Ravulo 2015 University of Western Sydney ISBN 978-1-74108-359-0 PAGE 2 – PACIFIC COMMUNITES IN AUSTRALIA Table of Contents OVERVIEW 4 Figure 14 (QALLP) Non-School Qualification: Level of Education 13 (a) Pacific people in Australia 4 Figure 15 (HSCP) Highest Year of School Completed – (b) Previous research on Pacific people in Australia 5 based on people aged 18 or older 14 i. Social Risk & Protective Factors 6 Figure 16 (TYSTAP) Educational Institution: Attendee Status 14 ii. Cultural Perspectives 7 Figure 17 (INCP) Total Personal Income (weekly) 15 (c) Purpose of report 8 Figure 18 (HRSP) Hours Worked 15 (d) Collection of data & analysis 8 Figure 19 (INDP) Industry of Employment 15 Figure 20 (INDP) Industry of Employment – Construction 15 KEY FINDINGS 11 Figure 21 Labour Force Status and Hours Worked (a) Demographic 11 Not Stated (LFHRP) 16 (b) Education & Training 13 Figure 22 (MTWP) Method of Travel to Work -

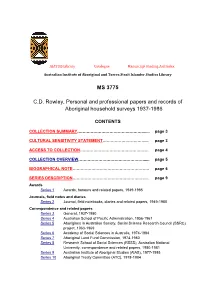

MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and Professional Papers and Records Of

AIATSIS Library Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 3775 C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys 1937-1986 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY……………………………….…………...... page 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT…………………………..... page 3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION…………………………………………… page 4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW…………………………….……………..... page 5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………………………… page 6 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………... page 9 Awards Series 1 Awards, honours and related papers, 1949-1985 Journals, field notes and diaries Series 2 Journal, field notebooks, diaries and related papers, 1949-1980 Correspondence and related papers Series 3 General, 1937-1980 Series 4 Australian School of Pacific Administration, 1956-1961 Series 5 Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council (SSRC) project, 1963-1969 Series 6 Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, 1974-1984 Series 7 Aboriginal Land Fund Commission, 1974-1980 Series 8 Research School of Social Sciences (RSSS), Australian National University, correspondence and related papers, 1980-1981 Series 9 Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS), 1977-1985 Series 10 Aboriginal Treaty Committee (ATC), 1978-1984 MS 3775: C.D. Rowley, Personal and professional papers and records of Aboriginal household surveys, 1937-1986 Series 11 Sundry, 1965-1981 Research project files Series 12 UNESCO Mission on Adult & Workers’ Education to S-E Asia, 1954-55 Series 13 Aborigines in -

Sydney Metro Pitt Street South Over Station Development

Sydney Metro Pitt Street South Over Station Development Build to Rent Overview State Significant Development Development Application Revision B SMCSWSPS‐OXF‐OSS‐PL‐REP‐000001 Document Control Revision B Prepared for issue: Lucinda Mander‐Jones Date: 18 May 2020 Reviewed for issue: Nellie O’Keeffe Date: 18 April 2020 Approved for issue: Ian Lyon Date: 18 April 2020 Contents Common Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 Background ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1. State Significant Secretary’s Environmental Assessment Requirements ........................... 6 2. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 3. Oxford Property Group Overview ....................................................................................... 7 Project Summary ............................................................................................................................... 9 4. Project Objectives ............................................................................................................... 9 5. What is Build to Rent ? .................................................................................................... -

THE JEWISH POPULATION of AUSTRALIA Key Findings from the 2011 Census

THE JEWISH POPULATION OF AUSTRALIA Key findings from the 2011 Census Dr David Graham All rights reserved © JCA First published 2014 JCA 140-146 Darlinghurst Rd Darlinghurst NSW 2023 http://www.JCA.org.au ISBN: 978-0-9874195-7-6 This work is copyright. Apart for any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of it may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the publisher. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................4 What is a census and who is included?.........................................................................................4 Why does the census matter? .........................................................................................................5 Notes about the data ........................................................................................................................5 AUSTRALIA’S JEWISH POPULATION IN CONTEXT .................................................................6 Global Jewish context.......................................................................................................................6 -

Sydney, Australia by Joe Flood

The case of Sydney, Australia by Joe Flood Contact Source: CIA factbook Dr. Joe Flood Urban Resources 37 Horne St Elsternwick Vic 3185, AUSTRALIA Tel. +61 3 9532 8492 Fax. +61 3 9532 4325 E-mail: [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION Australia, the “Great South Land” is the size of conti- Australia has been called the “Lucky Country” – with nental USA, but has a population of only 19 million. some justification. From 1890 to1920 it had the highest Much of Australia is extremely arid and unsuited to culti- per capita income in the world. It was the first country to vation or settlement, and the bulk of the people live in introduce a social service safety net through universal the temperate south-eastern region and other coastal age and other pensions. It consistently rates among the areas. top few countries in terms of human development and Australia was settled as six separate British colonies liveability indices. It is regarded as one of the world’s during the period 1788-1840, displacing some 750,000 most egalitarian nations in which everyone gets a indigenous inhabitants to the more remote parts of the chance to improve their situation. Yet the largest cities continent1. Following a sheep farming boom in the latter have had slums in the past to equal those of any coun- half of the nineteenth century and the discovery of gold try. Despite a century of slum clearance and redevelop- in the 1950s, the colonies prospered and joined to form ment, it is still easy to identify areas of considerable the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901. -

Undermining Mabo the Shaming of Manning Clark on Your Way, Sister

Vol. 3 No. 8 October 1993 $5.00 Undermining Mabo On your way, sister Frank Brennan Pamela Foulkes The shaming of Manning Clark Trading in union futures Rosamund Dalziel! PauiRodan In Memoriam D.J.O'H One thirty. This is the time I saw you last Braving death with a grin in the stilled ward. Invaded and insulted, you stood fast, Ready to fight, or ford The cold black stream that rings us all about Like Ocean. Some of it got into your eyes That afternoon, smarting you not to doubt But to a new surprise At what sheer living brings-as once Yeats Braced in a question bewilderment, love and dying. As the flesh declines, the soul interrogates, Failing and stili trying. On a field of green, bright water in their shade, Wattles, fused and diffused by a molten star, Are pledging spring to Melbourne. Grief, allayed A little, asks how you are. 'Green is life's golden tree', said Goethe, and I hope that once again you're in a green Country, gold-fired now, taking your stand, A seer amidst the seen. Peter Steele In Memory of Dinny O'Hearn I Outcome, upshot, lifelong input, All roads leading to a dark Rome, We stumble forward, foot after foot: II You have taken your bat and gone home. Though you had your life up to pussy's bow, He disappeared in the full brilliance of winter, The innings wound up far too quick yellow sun unfailing, the voice of Kennett But the nature of knowledge, you came to know, utterly itself away on Shaftesbury A venue, Is itself the flowering of rhetoric. -

The Granite Belt Naturalist

Monthly Newsletter of the Stanthorpe Field Naturalist Club Inc. –November 2019 Vol The Granite Belt Naturalist Mail Address: Stanthorpe Field Naturalist Club Inc, PO Box 154, Stanthorpe Qld. 4380 [email protected] Web site https://mysd.com.au/fieldnats/ AIMS OF THE CLUB 1. To study all branches of Natural History 2. Preservation of the Flora and Fauna of Queensland 3. Encouragement of a spirit of protection towards native birds, animals and plants 4. To assist where possible in scientific research 5. To publish a monthly newsletter and post it to members Meetings 4th Wednesday of each month at QCWA Rooms, Victoria Street, Stanthorpe, at 7.30pm Outings: The Sunday preceding the 4th Wednesday of each month The Pyramids, Girraween National Park (Saturday outings as pre-arranged) Subs: Single $20.00, Family $30.00 per annum, July to June CLUB OFFICE BEARERS – 2019/2020 The Club thanks the Queensland Country Credit Union for President Jeff Campbell 46811420 their donation that enabled us to buy a printer. Vice-presidents Kris Carnell 46835268 Peter Haselgrove 46837255 Secretary Rob McCosker 46835371 Stanthorpe Field Naturalists is a group member of Granite Treasurer Gunter Maywald 46810674 Borders Landcare. Newsletter Editor Margaret Carnell 46835268 Publicity Officer Jeff Campbell 46812008 Librarian Laura Maywald 46810674 Management Committee: President, Vice-Presidents, Secretary, Treasurer The Granite Belt Naturalist 2019 Vol. 524 SCALE OF DIFFICULTY FOR WALKS Coming Up ON NATS OUTINGS th 1. Flat walking, road or track Sunday 24 November: Basket Swamp with 2. Road or track, gentle hills Jeff Campbell 3. Track, some hilly sections th 4. -

Assyrian Community Capacity Building in Fairfield City

ASSYRIAN COMMUNITY CAPACITY BUILDING IN FAIRFIELD CITY GREG GOW WITH ASHUR ISAAC PAUL GORGEES MARLIN BABAKHAN KARDONIA DAAWOD © 2005 CENTRE FOR CULTURAL RESEARCH AND ASSYRIAN WORKERS’ NETWORK ISBN 1 74108 112 2 PUBLISHED BY THE CENTRE FOR CULTURAL RESEARCH, UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY CENTRE FOR CULTURAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY PARRAMATTA CAMPUS EBA LOCKED BAG 1797 PENRITH SOUTH DC 1797 NSW AUSTRALIA www.uws.edu.au/ccr DESIGN: ANNA LAZAR, ODESIGN PRINTING: UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY COVER MODEL: JOSEPH SOLOMON Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY III ABOUT THE AUTHORS IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V LIST OF ACRONYMS VI Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 1 Assyrians: a global community ............................................................................... 3 2 Fairfi eld City: Australia’s Assyrian centre .............................................................. 6 2.1 Perceptions of Fairfi eld 2.2 Settlement history 3 Statistical profi le of the community ....................................................................... 10 3.1 Population, origin and migration 3.2 Family composition and age distribution 3.3 Religious affi liations 3.4 Language and education 3.5 Labour force status 3.6 Distribution by suburbs and tenure type 4 Research approach ................................................................................................... 13 5 Assyrian organisations and community infrastructure ...................................... -

Gos on the Route Choice Behaviour of Car Drivers

Modelling the Effect of the Number of Stop-&-gos on the Route Choice Behaviour of Car Drivers By Neeraj Saxena M. Tech. (Transportation), B. Tech. (Civil) A thesis presented in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Faculty of Engineering The University of New South Wales August 2017 ॐ जननी जꅍमभूमम�च व셍गादपि 셍रीयसी । Mother and Motherland are superior to Heaven. 셍ु셁 셍ोबिꅍद दोउ खडे कगके लग셍ँू िगँय । िमलहगरी 셍ु셁 आिने 셍ोबिꅍद ददयो ितगय ॥ Guru and God both are here to whom should I first bow. All glory be unto the guru path to God who did bestow. This thesis is dedicated to my Parents, Gurus and Motherland Neeraj Saxena iii ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …… ……… Date …… 28/08/2017 ……. -

Chapter 1 1 Towards a Diachronic, Functional Account of Language in Context

Chapter 1 1 Towards a diachronic, functional account of language in context “Our sense of the past, and our sense of the ways in which the past impinges on us today, become increasingly dependent on an ever expanding reservoir of mediated symbolic forms.” (Thompson, 1995: 34) “The context of a written text of the past is more complex, and more difficult to evaluate and make abstraction from, than that of a contemporary spoken language text.” (Halliday, 1959: 13) 1.1 Introduction to the thesis This thesis presents an investigation of the diachronic construction of meaning in news reports about the events that mark the end of conflict, focusing on seven overseas wars in which Australian military personnel have been involved, and making a case study of the reporting in the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH or the Herald). The quotations used to introduce this chapter reflect the dual motivations for this study: an interest in texts that construe the social contexts of the past and what they indicate to us in the present about our language and our culture; and an interest in exploring changes in context within a particular register of English and how this can be managed using current linguistic models. The reporting of war always seems to capture the attention of the general public and generate a large volume of material, not to mention generate higher commercial value than ordinary news (see e.g. Read, 1999). For example, on the 21st March 2003, the first day of reporting after the beginning of the War on Iraq, the news of the outbreak of war occupied the first eight pages of the 24-page main section of the Sydney Morning Herald. -

On the Flora of Australia

L'IBRARY'OF THE GRAY HERBARIUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY. BOUGHT. THE FLORA OF AUSTRALIA, ITS ORIGIN, AFFINITIES, AND DISTRIBUTION; BEING AN TO THE FLORA OF TASMANIA. BY JOSEPH DALTON HOOKER, M.D., F.R.S., L.S., & G.S.; LATE BOTANIST TO THE ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION. LONDON : LOVELL REEVE, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN. r^/f'ORElGN&ENGLISH' <^ . 1859. i^\BOOKSELLERS^.- PR 2G 1.912 Gray Herbarium Harvard University ON THE FLORA OF AUSTRALIA ITS ORIGIN, AFFINITIES, AND DISTRIBUTION. I I / ON THE FLORA OF AUSTRALIA, ITS ORIGIN, AFFINITIES, AND DISTRIBUTION; BEIKG AN TO THE FLORA OF TASMANIA. BY JOSEPH DALTON HOOKER, M.D., F.R.S., L.S., & G.S.; LATE BOTANIST TO THE ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION. Reprinted from the JJotany of the Antarctic Expedition, Part III., Flora of Tasmania, Vol. I. LONDON : LOVELL REEVE, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN. 1859. PRINTED BY JOHN EDWARD TAYLOR, LITTLE QUEEN STREET, LINCOLN'S INN FIELDS. CONTENTS OF THE INTRODUCTORY ESSAY. § i. Preliminary Remarks. PAGE Sources of Information, published and unpublished, materials, collections, etc i Object of arranging them to discuss the Origin, Peculiarities, and Distribution of the Vegetation of Australia, and to regard them in relation to the views of Darwin and others, on the Creation of Species .... iii^ § 2. On the General Phenomena of Variation in the Vegetable Kingdom. All plants more or less variable ; rate, extent, and nature of variability ; differences of amount and degree in different natural groups of plants v Parallelism of features of variability in different groups of individuals (varieties, species, genera, etc.), and in wild and cultivated plants vii Variation a centrifugal force ; the tendency in the progeny of varieties being to depart further from their original types, not to revert to them viii Effects of cross-impregnation and hybridization ultimately favourable to permanence of specific character x Darwin's Theory of Natural Selection ; — its effects on variable organisms under varying conditions is to give a temporary stability to races, species, genera, etc xi § 3.