The Shadow of Empire: Christian Missions, Colonial Policy, and Democracy in Postcolonial Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives William Prevette University of Edinburgh, Ir [email protected]

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Edinburgh Centenary Series Resources for Ministry 1-1-2014 Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives William Prevette University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Keith White University of Edinburgh, [email protected] C. Rosalee Velloso da Silva University of Edinburgh, [email protected] D. J. Konz University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Prevette, William; White, Keith; da Silva, C. Rosalee Velloso; and Konz, D. J., "Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives" (2014). Edinburgh Centenary Series. Book 24. http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary/24 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Resources for Ministry at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Edinburgh Centenary Series by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGNUM EDINBURGH CENTENARY SERIES Volume 24 Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives REGNUM EDINBURGH CENTENARY SERIES The centenary of the World Missionary Conference of 1910, held in Edinburgh, was a suggestive moment for many people seeking direction for Christian mission in the 21st century. Several different constituencies within world Christianity held significant events around 2010. From 2005, an international group worked collaboratively to develop an intercontinental and multi- denominational project, known as Edinburgh 2010, based at New College, University of Edinburgh. This initiative brought together representatives of twenty different global Christian bodies, representing all major Christian denominations and confessions, and many different strands of mission and church life, to mark the centenary. -

James Cropper, John Philip and the Researches in South Africa

JAMES CROPPER, JOHN PHILIP AND THE RESEARCHES IN SOUTH AFRICA ROBERT ROSS IN 1835 James Cropper, a prosperous Quaker merchant living in Liverpool and one of the leading British abolitionists, wrote to Dr John Philip, the Superintendent of the London Missionary Society in South Africa, offering to finance the republication of the latter's book, Researches in South Africa, which had been issued seven years earlier. This offer was turned down. This exchange was recorded by William Miller Macmillan in his first major historical work, The Cape Coloured Question,1 which was prirnarily concerned with the struggles of Dr John Philip on behalf of the so-called 'Cape Coloureds'. These resulted in Ordinance 50 of 1828 and its confirmation in London, which lifted any civil disabilities for free people of colour. The correspondence on which it was based, in John Philip's private papers, was destroyed in the 1931 fire in the Gubbins library, Johannesburg, and I have not been able to locate any copies at Cropper's end. Any explanation as to why these letters were written must therefore remain speculative. Nevertheless, even were the correspondence extant, it is unlikely that it would contain a satisfactory explanation of what at first sight might seem a rather curious exchange. The two men had enough in common with each other, and knew each other's minds well enough, for them merely to give their surface motivation, and not to be concerned with deeper ideological justification. And the former level can be reconstructed fairly easily. Cropper, it may be assumed, saw South Africa as a 'warning for the West Indies', which was especially timely in 1835 as the British Caribbean was having to adjust to the emancipation of its slaves.2 The Researches gave many examples of how the nominally free could still be maintained in effective servitude, and Cropper undoubtedly hoped that this pattern would not be repeated. -

The Other Side of the Story: Attempts by Missionaries to Facilitate Landownership by Africans During the Colonial Era

Article The Other Side of the Story: Attempts by Missionaries to Facilitate Landownership by Africans during the Colonial Era R. Simangaliso Kumalo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2098-3281 University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article provides a critique of the role played by progressive missionaries in securing land for the African people in some selected mission stations in South Africa. It argues that, in spite of the dominant narrative that the missionaries played a role in the dispossession of the African people of their land, there are those who refused to participate in the dispossession. Instead, they used their status, colour and privilege to subvert the policy of land dispossession. It critically examines the work done by four progressive missionaries from different denominations in their attempt to subvert the laws of land dispossession by facilitating land ownership for Africans. The article interacts with the work of Revs John Philip (LMS), James Allison (Methodist), William Wilcox and John Langalibalele Dube (American Zulu Mission [AZM]), who devised land redistributive mechanisms as part of their mission strategies to benefit the disenfranchised Africans. Keywords: London Missionary Society; land dispossession; Khoisan; mission stations; Congregational Church; Inanda; Edendale; Indaleni; Mahamba Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/6800 https://upjournals.co.za/index.php/SHE/index ISSN 2412-4265 (Online) ISSN 1017-0499 (Print) Volume 46 | Number 2 | 2020 | #6800 | 17 pages © The Author(s) 2020 Published by the Church History Society of Southern Africa and Unisa Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/) Kumalo Introduction In our African culture, we are integrally connected to the land from the time of our birth. -

Octor of ^F)Ilos(Opi)P «&=• /•.'' in St EDUCATION

^ CONTRIBUTION OF CHRISTIAN MISSIONARIES TOWARDS DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN ASSAM SINCE INDEPENDENCE ABSTRACT OF THE <^ V THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF octor of ^f)ilos(opI)p «&=• /•.'' IN St EDUCATION wV", C BY •V/ SAYEEDUL HAQUE s^^ ^ 1^' UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ALI AHMAD DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2009 ^&. ABSTRACT Title of the study: "Contribution of Christian Missionaries Towards Development of Secondary Education in Assam Since Independence" Education is the core of all religions, because it prepares the heathen mind for the proper understanding and acceptance of the supremacy of his Creator. Thus, acquisition of Knowledge and learning is considered as an act of salvation in Christianity. The revelation in Bible clearly indicates that the Mission of Prophet of Christianity, Jesus Christ, is to teach his people about the tenets of Christianity and to show them the true light of God. As a true follower of Christ, it becomes the duty of every Christian to act as a Missionary of Christianity. The Missionaries took educational enterprise because they saw it as one of the most effective means of evangelization. In India, the European Missionaries were regarded as the pioneers of western education, who arrived in the country in the last phase of the fifteenth century A.D. The Portuguese Missionaries were the first, who initiated the modem system of education in India, when St. Xavier started a University near Bombay in 1575 A.D. Gradually, other Europeans such as the Dutch, the Danes, the French and the English started their educational efforts. -

Thesis Hum 2007 Mcdonald J.Pdf

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town 'When Shall These Dry Bones Live?' Interactions between the London Missionary Society and the San Along the Cape's North-Eastern Frontier, 1790-1833. Jared McDonald MCDJAR001 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2007 University of Cape Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature:_fu""""',_..,"<_l_'"'"-_(......\b __ ~_L ___ _ Date: 7 September 2007 "And the Lord said to me, Prophe,\y to these bones, and scry to them, o dry bones. hear the Word ofthe Lord!" Ezekiel 37:4 Town "The Bushmen have remained in greater numbers at this station ... They attend regularly to hear the Word of God but as yet none have experiencedCape the saving effects ofthe Gospe/. When shall these dry bones oflive? Lord thou knowest. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

McDonald, Jared. (2015) Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan identity and assimilation in the Cape Colony, c. 1795- 1858. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/22831/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan Identity and Assimilation in the Cape Colony, c.1795-1858 Jared McDonald Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in History 2015 Declaration for PhD Thesis I declare that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the thesis which I present for examination. -

Working Papers in African Studies No. 269

Working Papers in African Studies No. 269 A History of Christianity in Nigeria: A Bibliography of Secondary Literature D. Dmitri Hurlbut Working Papers in African Studies African Studies Center Pardee School of Global Studies Boston University 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Boston University or the African Studies Center. Series Editor: Michael DiBlasi Production Manager: Sandra McCann African Studies Center Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies Boston University 232 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 Tel: 617-353-7306 Fax: 617-353-4975 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.bu.edu/africa/publications © 2017, by the author ii Working Papers in African Studies No. 269 (2017) The History of Christianity in Nigeria: A Bibliography of Secondary Literature* By D. Dmitri Hurlbut Introduction As long as scholars have been writing about the history of Nigeria, they have been writing about Christianity. After more than sixty years, however, it is time to take stock of this vast body of literature, and get a sense of where we have been and where we are going. It is my hope that the compilation of this relatively comprehensive bibliography, and a brief discussion of some of the gaps that need to be filled in the literature, will inspire scholars to take their historical research in exciting and novel directions. Based on a reading of this bibliography, I would like to suggest that future research into the history of Christianity in Nigeria should be directed in three broad directions. First, historians need to focus more research on the development of mainline mission churches following independence, because the historiography remains skewed in favor of independent churches. -

Philip De La Mare, Pioneer Industrialist

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1959 Philip De La Mare, Pioneer Industrialist Leon R. Hartshorn Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hartshorn, Leon R., "Philip De La Mare, Pioneer Industrialist" (1959). Theses and Dissertations. 4770. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4770 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. To my father whose interest, love, kindness and generosity have made not only this endeavor but many others possible. PHILIP DE LA MARE PIONEER INDUSTRIALIST A Thesis Submitted to The College of Religious Instruction Brigham Young University Provo, Utah In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Leon R. Hartshorn July 1959 ACKNOWLEDGMENT Seldom, if ever, do we accomplish anything alone. The confidence and support of family, friends and interested individuals have made an idea a reality* I express my most sincere thanks to my devoted wife, who has taken countless hours from her duties as a homemaker and mother to assist and encourage me in this endeavor, I am grateful to my advisors: Dr. Russell R. Rich for his detailed evaluation of this writing and for his friendliness and kindly interest and to Dr. B. West Belnap for his help and encouragement. My thanks to President Alex F. -

VOL 36, ISSUE 3 on Race and Colonialism WELCOME to THIS EDITION of ANVIL

ANVIL Journal of Theology and Mission Faultlines in Mission: Reflections VOL 36, ISSUE 3 on Race and Colonialism WELCOME TO THIS EDITION OF ANVIL ANVIL: Journal of Theology and Mission Lusa Nsenga-Ngoy VOL 36, ISSUE 3 2 ANVIL: JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY AND MISSION – VOLUME 36: ISSUE 3 THE EDITORIAL While it is premature to assess the legacy of this year in history, we can certainly agree that 2020 has brought to the fore the imperative need to revisit the past, paying particular attention to societal and systemic fractures adversely impacting the lives of many around the globe. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, millions of people took to the streets of our cities demanding radical change, and calling for the toppling of an old order and its symbols of power, objectification and commodification. This issue of Anvil is inspired by a willingness to Harvey Kwiyani’s article offers us a crystal-clear view of offer an introspective response to this global wave how white privilege and white supremacy have provided of protest calling for racial justice and asking with the buttresses for empire and have made mission in insistence whether black lives do indeed matter in our their own image. To illustrate this, he movingly weaves societies and institutions. It felt imperative to ask the his own story from his childhood in Malawi to living in question of Church Mission Society and its particular George Floyd’s city of Minneapolis to now forming part contribution to the subject both in its distant and more of the tiny minority of black and brown people who contemporary history. -

Church Mission Society Believes That All of God's

CHURCH MISSION SOCIETY BELIEVES THAT ALL OF GOD’S PEOPLE ARE CALLED TO JOIN IN GOD’S MISSION: TO BRING CHALLENGE, CHANGE, HOPE AND FREEDOM TO OUR WORLD. AS A COMMUNITY OF PEOPLE IN MISSION, WE WANT TO HELP AS MANY PEOPLE AS POSSIBLE BE SET FREE TO PUT THIS CALL Community Handbook 2017 INTO ACTION – WHETHER THAT MEANS GOING OVERSEAS OR OVER THE ROAD. Church Mission Society, Watlington Road, Oxford, OX4 6BZ T: +44 (0)1865 787400 E: [email protected] churchmissionsociety.org /churchmissionsociety @cmsmission Church Mission Society is a mission community acknowledged by the Church of England. Registered in England and The call in action Wales, charity number 1131655, company number 6985330. 1 CHURCHMISSIONSOCIETY.ORG As Christian people we are a sent people. The first people Jesus sent in mission were 1. WELCOME an inauspicious bunch, huddled together behind barred and bolted doors. But their TO THE fear was no obstacle to Jesus’ purposes for them. He gives them Philip, centre, at a mission training event his peace, he shares COMMUNITY in whatever your particular call his Spirit with them – may be: whether that be to your and he sends them. next-door neighbour or to your And the manner of his sending of neighbours on the other side of the them is special: “As the Father has world. And I hope this community sent me, even so I am sending you.” handbook will help resource you to These first Christians are sent just live your life of mission, knowing as the Father had sent the Son, and that you do not do so alone. -

Church Mission Society

CHURCH MISSION SOCIETY Job description Post: Mission Development Manager for Latin America Responsible to: Director of International Mission Team: International Mission Location: Currently envisaged to be Lima or Buenos Aires, after an extended induction period in the CMS office in Oxford, UK Grade: TBA Hours: Full time, 35 hours per week Introduction Church Mission Society believes that all God’s people are called to join in God’s mission: bringing challenge, change, hope and freedom to our world. For some this will mean going overseas; for others it will mean going over the road. Whatever the case, we want to set people free to put their call into action. Currently, there are hundreds of Church Mission Society people working in 40+ countries across Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, Europe and the UK. Church Mission Society was founded in 1799 by William Wilberforce, John Newton and other Christians whose hearts were stirred to put their faith into action. Since then, thanks to the generous and prayerful support of God’s people, we have helped support over 10,000 people in mission worldwide. CMS is also committed to equipping the church in Britain for mission today, not least through receiving the gifts of the global church in mission. As an Acknowledged Community of the Church of England we are governed by four values: we seek to be people who are pioneering, evangelistic, relational and faithful. To find out much more about the work of our community please visit: www.churchmissionsociety.org 1 Job Context The contemporary paradigm of mission is one of everyone from anywhere being able to participate in God’s global mission. -

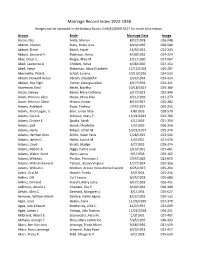

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images Can Be Accessed in the Indiana Room

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images can be accessed in the Indiana Room. Call (812)949-3527 for more information. Groom Bride Marriage Date Image Aaron, Elza Antle, Marion 8/12/1928 026-048 Abbott, Charles Ruby, Hallie June 8/19/1935 030-580 Abbott, Elmer Beach, Hazel 12/9/1922 022-243 Abbott, Leonard H. Robinson, Berta 4/30/1926 024-324 Abel, Oscar C. Ringle, Alice M. 1/11/1930 027-067 Abell, Lawrence A. Childers, Velva 4/28/1930 027-154 Abell, Steve Blakeman, Mary Elizabeth 12/12/1928 026-207 Abernathy, Pete B. Scholl, Lorena 10/15/1926 024-533 Abram, Howard Henry Abram, Elizabeth F. 3/24/1934 029-414 Absher, Roy Elgin Turner, Georgia Lillian 4/17/1926 024-311 Ackerman, Emil Becht, Martha 10/18/1927 025-380 Acton, Dewey Baker, Mary Cathrine 3/17/1923 022-340 Adam, Herman Glen Harpe, Mary Allia 4/11/1936 031-273 Adam, Herman Glenn Hinton, Esther 8/13/1927 025-282 Adams, Adelbert Pope, Thelma 7/14/1927 025-255 Adams, Ancil Logan, Jr. Eiler, Lillian Mae 4/8/1933 028-570 Adams, Cecil A. Johnson, Mary E. 12/21/1923 022-706 Adams, Crozier E. Sparks, Sarah 4/1/1936 031-250 Adams, Earl Snook, Charlotte 1/5/1935 030-250 Adams, Harry Meyer, Lillian M. 10/21/1927 025-376 Adams, Herman Glen Smith, Hazel Irene 2/28/1925 023-502 Adams, James O. Hallet, Louise M. 4/3/1931 027-476 Adams, Lloyd Kirsch, Madge 6/7/1932 028-274 Adams, Robert A.