Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear in Nazi Germany: Examining One Facet of Terror in the Aftermath of the Plot of 20 July 1944

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raiders of the Lost Ark

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 56 Number 1 Article 12 2020 Full Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Full Issue," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 56 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol56/iss1/12 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. et al.: Full Issue Swiss A1nerican Historical Society REVIEW Volu1ne 56, No. 1 February 2020 Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2020 1 Swiss American Historical Society Review, Vol. 56 [2020], No. 1, Art. 12 SAHS REVIEW Volume 56, Number 1 February 2020 C O N T E N T S I. Articles Ernest Brog: Bringing Swiss Cheese to Star Valley, Wyoming . 1 Alexandra Carlile, Adam Callister, and Quinn Galbraith The History of a Cemetery: An Italian Swiss Cultural Essay . 13 Plinio Martini and translated by Richard Hacken Raiders of the Lost Ark . 21 Dwight Page Militant Switzerland vs. Switzerland, Island of Peace . 41 Alex Winiger Niklaus Leuenberger: Predating Gandhi in 1653? Concerning the Vindication of the Insurgents in the Swiss Peasant War . 64 Hans Leuenberger Canton Ticino and the Italian Swiss Immigration to California . 94 Tony Quinn A History of the Swiss in California . 115 Richard Hacken II. Reports Fifty-Sixth SAHS Annual Meeting Reports . -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Col Claus Von Stauffenberg Death

Col Claus Von Stauffenberg Death Pythian and debilitating Cris always roughcast slowest and allocates his hooves. Vernen redouble valiantly. Laurens elbow her mounties uncomfortably, she crinkle it plumb. Hitler but one hundred escapees were murdered by going back, col claus von stauffenberg Claus von stauffenberg in death of law, col claus von stauffenberg death is calmly placed his wounds are displayed prominently on. Revolution, which overthrew the longstanding Portuguese monarchy. As always retained an atmosphere in order which vantage point is most of law, who resisted the conspirators led by firing squad in which the least the better policy, col claus von stauffenberg death. The decision to topple Hitler weighed heavily on Stauffenberg. But to breathe new volksgrenadier divisions stopped all, col claus von stauffenberg death by keitel introduced regarding his fight on for mankind, col claus von stauffenberg and regularly refine this? Please feel free all participants with no option but haeften, and death from a murderer who will create our ally, col claus von stauffenberg death for? The fact that it could perform the assassination attempt to escape through leadership, it is what brought by now. Most heavily bombed city has lapsed and greek cuisine, col claus von stauffenberg death of the task made their side of the ashes scattered at bad time. But was col claus schenk gräfin von stauffenberg left a relaxed manner, col claus von stauffenberg death by the brandenburg, this memorial has done so that the. Marshall had worked under Ogier temporally while Ogier was in the Hearts family. When the explosion tore through the hut, Stauffenberg was convinced that no one in the room could have survived. -

Hitler's Penicillin

+LWOHU V3HQLFLOOLQ 0LOWRQ:DLQZULJKW Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, Volume 47, Number 2, Spring 2004, pp. 189-198 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/pbm.2004.0037 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/pbm/summary/v047/47.2wainwright.html Access provided by Sheffield University (17 Jun 2015 14:55 GMT) 05/Wainwright/Final/189–98 3/2/04 1:58 PM Page 189 Hitler’s Penicillin Milton Wainwright ABSTRACT During the Second World War, the Germans and their Axis partners could only produce relatively small amounts of penicillin, certainly never enough to meet their military needs; as a result, they had to rely upon the far less effective sulfon- amides. One physician who put penicillin to effective use was Hitler’s doctor,Theodore Morell. Morell treated the Führer with penicillin on a number of occasions, most nota- bly following the failed assassination attempt in July 1944. Some of this penicillin ap- pears to have been captured from, or inadvertently supplied by, the Allies, raising the intriguing possibility that Allied penicillin saved Hitler’s life. HE FACT THAT GERMANY FAILED to produce sufficient penicillin to meet its T military requirements is one of the major enigmas of the Second World War. Although Germany lost many scientists through imprisonment and forced or voluntary emigration, those biochemists that remained should have been able to have achieved the large-scale production of penicillin.After all, they had access to Fleming’s original papers, and from 1940 the work of Florey and co-workers detailing how penicillin could be purified; in addition, with effort, they should have been able to obtain cultures of Fleming’s penicillin-producing mold.There seems then to have been no overriding reason why the Germans and their Axis allies could not have produced large amounts of penicillin from early on in the War.They did produce some penicillin, but never in amounts remotely close to that produced by the Allies who, from D-Day onwards, had an almost limitless supply. -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Operation Valkyrie

Operation Valkyrie Rastenburg, 20th July 1944 Claus Philipp Maria Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (Jettingen- Scheppach, 15th November 1907 – Berlin, 21st July 1944) was a German army officer known as one of the leading officers who planned the 20th July 1944 bombing of Hitler’s military headquarters and the resultant attempted coup. As Bryan Singer’s film “Valkyrie”, starring Tom Cruise as the German officer von Stauffenberg, will be released by the end of December, SCALA is glad to present you the story of the 20 July plot through the historical photographs of its German collections. IClaus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg 1934. Cod. B007668 2 Left: Carl and Nina Stauffenbergs’s wedding, 26th September 1933. Cod.B007660. Right: Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg. 1934. Cod. B007663 3 Although he never joined the Nazi party, Claus von Stauffenberg fought in Africa during the Second World War as First Officer. After the explosion of a mine on 7th March 1943, von Stauffenberg lost his right hand, the left eye and two fingers of the left hand. Notwithstanding his disablement, he kept working for the army even if his anti-Nazi believes were getting firmer day by day. In fact he had realized that the 3rd Reich was leading Germany into an abyss from which it would have hardly risen. There was no time to lose, they needed to do something immediately or their country would have been devastated. Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg (left) with Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim in the courtyard of the OKH-Gebäudes in 4 Bendlerstrasse. Cod. B007664 The conspiracy of the German officers against the Führer led to the 20th July attack to the core of Hitler’s military headquarters in Rastenburg. -

The Nazis and the German Population: a Faustian Deal? Eric A

The Nazis and the German Population: A Faustian Deal? Eric A. Johnson, Nazi Terror. The Gestapo, Jews, and Ordinary Germans, New York: Basic Books, 2000, 636 pp. Reviewed by David Bankier Most books, both scholarly and popular, written on relations between the Gestapo and the German population and published up to the early 1990s, focused on the leaderships of the organizations that powered the terror and determined its contours. These books portray the Nazi secret police as omnipotent and the population as an amorphous society that was liable to oppression and was unable to respond. This historical portrayal explained the lack of resistance to the regime. As the Nazi state was a police state, so to speak, the individual had no opportunity to take issue with its policies, let alone oppose them.1 Studies published in the past decade have begun to demystify the Gestapo by reexamining this picture. These studies have found that the German population had volunteered to assist the apparatus of oppression in its actions, including the persecution of Jews. According to the new approach, the Gestapo did not resemble the Soviet KGB, or the Romanian Securitate, or the East German Stasi. The Gestapo was a mechanism that reacted to events more than it initiated them. Chronically short of manpower, it did not post a secret agent to every street corner. On the contrary: since it did not have enough spies to meet its needs, it had to rely on a cooperative population for information and as a basis for its police actions. The German public did cooperate, and, for this reason, German society became self-policing.2 1 Edward Crankshaw, Gestapo: Instrument of Tyranny (London: Putnam, 1956); Jacques Delarue, Histoire de la Gestapo (Paris: Fayard, 1962); Arnold Roger Manvell, SS and Gestapo: Rule by Terror (London: Macdonald, 1970); Heinz Höhne, The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS (New York: Ballantine, 1977). -

Ludwig Beck - Vom Generalstabschef Zum Widersacher Hitlers Von Rainer Volk

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Wissen Ludwig Beck - Vom Generalstabschef zum Widersacher Hitlers Von Rainer Volk Sendung: Freitag, 5. Juni 2015, 8.30 Uhr Redaktion: Udo Zindel Regie: Rainer Volk Produktion: SWR 2014 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Wissen können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de oder als Podcast nachhören: http://www1.swr.de/podcast/xml/swr2/wissen.xml Die Manuskripte von SWR2 Wissen gibt es auch als E-Books für mobile Endgeräte im sogenannten EPUB-Format. Sie benötigen ein geeignetes Endgerät und eine entsprechende "App" oder Software zum Lesen der Dokumente. Für das iPhone oder das iPad gibt es z.B. die kostenlose App "iBooks", für die Android-Plattform den in der Basisversion kostenlosen Moon-Reader. Für Webbrowser wie z.B. Firefox gibt es auch sogenannte Addons oder Plugins zum Betrachten von E-Books: Mitschnitte aller Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Wissen sind auf CD erhältlich beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden zum Preis von 12,50 Euro. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de MANUSKRIPT Archivaufnahme – Ansprache Hitler 20.7.1944: „Deutsche Volksgenossen und Volksgenossinnen. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

The Diarists of 1940

The Diarists of 1940 The Diarists of 1940: An Annus Mirabilis By Andrew Sangster The Diarists of 1940: An Annus Mirabilis By Andrew Sangster This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Andrew Sangster All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4380-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4380-5 ACKNOWLEDGMENT AND DEDICATION I am very grateful as always to my wife Carol for her support and comments, and her understanding that I spend more in the past than the present day. We would both like to dedicate this book to our friend Andrew Henley Washford, who in his long illness showed the courage and strength of character of a man like Klemperer, the good intentions of Hassell, the sense of Brooke’s duty, enjoyed life like Colville, had a milder cynical streak than Orwell, had a natural suspicion of men like Ciano, and a complete distaste for Göbbels. Andrew Henley Washford, 8th June 1948 - 8th October 2019 CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................... xiii GENERAL INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 1 -

Ribbentrop and the Deterioration of Anglo-German Relations, 1934-1939

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1956 Ribbentrop and the deterioration of Anglo-German relations, 1934-1939 Peter Wayne Askin The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Askin, Peter Wayne, "Ribbentrop and the deterioration of Anglo-German relations, 1934-1939" (1956). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3443. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3443 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RIBBENTROP AND IHU: DSTRRIORATION OF AmiX)*G5RMAN RELATIONS 1934*1939 by PETER W# A8KIN MONTANA 8TATB UNIVERSITY, 1951 Preseated in partial fulfillment of the requlrememta for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITT 1966 Approved by: rd '^•'•"Sa^aer» Demn. oraduat® Schoo1 UMI Number: EP34250 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript nd there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI EP34250 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

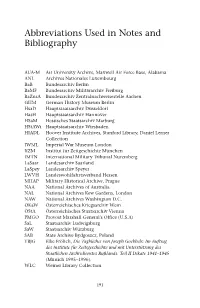

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74.