Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Littlewood Education Pack in Association with Essentialdrama.Com Joan Littlewood Education Pack

in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan LittlEWOOD Education pack in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan Littlewood Education PAck Biography 2 Artistic INtentions 5 Key Collaborators 7 Influences 9 Context 11 Productions 14 Working Method 26 Text Phil Cleaves Nadine Holdsworth Theatre Recipe 29 Design Phil Cleaves Further Reading 30 Cover Image Credit PA Image Joan LIttlewood: Education pack 1 Biography Early Life of her life. Whilst at RADA she also had Joan Littlewood was born on 6th October continued success performing 1914 in South-West London. She was part Shakespeare. She won a prize for her of a working class family that were good at verse speaking and the judge of that school but they left at the age of twelve to competition, Archie Harding, cast her as get work. Joan was different, at twelve she Cleopatra in Scenes from Shakespeare received a scholarship to a local Catholic for BBC a overseas radio broadcast. That convent school. Her place at school meant proved to be one of the few successes that she didn't ft in with the rest of her during her time at RADA and after a term family, whilst her background left her as an she dropped out early in 1933. But the outsider at school. Despite being a misft, connection she made with Harding would Littlewood found her feet and discovered prove particularly infuential and life- her passion. She fell in love with the changing. theatre after a trip to see John Gielgud playing Hamlet at the Old Vic. Walking to Find Work Littlewood had enjoyed a summer in Paris It had me on the edge of my when she was sixteen and decided to seat all afternoon. -

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Borstal Boy Free

FREE BORSTAL BOY PDF Brendan Behan | 384 pages | 27 Feb 1994 | Cornerstone | 9780099706502 | English | London, United Kingdom Borstal Boy by Brendan Behan Borstal Boy is a autobiographical book by Brendan Behan. Ultimately, Behan demonstrated by his skillful dialogue that working class Irish Borstal Boy and English Protestants actually had more in common with one Borstal Boy through class than they had supposed, and that alleged barriers of religion and ethnicity were merely superficial and imposed by a fearful middle class. The book was banned in Ireland for unspecified reasons in ; the ban expired in The play was a great success, winning McMahon a Tony Award for his adaptation. The play remains popular with both Irish and American audiences. The UK electropop group Chew Lips take their name from a character Borstal Boy the book. The novel was reissued by David R. Godine, Publisher in From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. For other uses, see Borstal Boy disambiguation. Main articles: Borstal Boy play and Borstal Boy film. The Glasgow Herald. October 23, Borstal Boy : novels Irish autobiographical novels Book censorship in the Republic of Ireland Irish novels adapted into films Novels by Brendan Behan Novels set in England Irish Borstal Boy novels 20th-century Irish novels Censored books. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit Borstal Boy history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Borstal Boy (film) - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track Borstal Boy books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

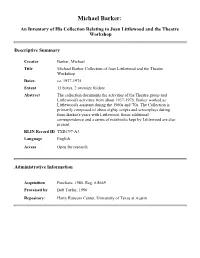

Michael Barker

Michael Barker: An Inventory of His Collection Relating to Joan Littlewood and the Theatre Workshop Descriptive Summary Creator Barker, Michael Title Michael Barker Collection of Joan Littlewood and the Theatre Workshop Dates: ca. 1937-1975 Extent 15 boxes, 2 oversize folders Abstract The collection documents the activities of the Theatre group and Littlewood's activities from about 1937-1975. Barker worked as Littlewood's assistant during the 1960s and '70s. The Collection is primarily composed of about eighty scripts and screenplays dating from Barker's years with Littlewood. Some additional correspondence and a series of notebooks kept by Littlewood are also present. RLIN Record ID TXRC97-A3 Language English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1980, Reg. # 8669 Processed by Bob Taylor, 1996 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Barker, Michael Biographical Sketch Michael Barker, who assembled this collection of Joan Littlewood materials, worked with her in the 1960s and '70s as an assistant and was involved both in theatrical endeavors as well as the street theater ventures. Joan Maud Littlewood was born into a working-class family in London's East End in October 1914. Early demonstrating an acute mind and an artistic bent she won scholarships to a Catholic school and then to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. Quickly realizing that RADA was neither philosophically nor socially congenial, she departed to study art. In 1934--still short of twenty years of age--she arrived in Manchester to work for the BBC. Littlewood soon met Jimmy Miller (Ewan MacColl) and collaborated with him in the Theatre of Action, a leftist drama group. -

Abbey Theatre's

Under the leadership of Artistic Director Barbara Gaines and Executive Director Criss Henderson, Chicago A NOTE FROM DIRECTOR CAITRÍONA MCLAUGHLIN Shakespeare has redefined what a great American Shakespeare theater can be—a company that defies When Neil Murray and Graham McLaren (directors of theatrical category. This Regional Tony Award-winning the Abbey Theatre) asked me to direct Roddy Doyle’s theater’s year-round season features as many as twenty new play Two Pints and tour it to pubs around productions and 650 performances—including plays, Ireland, I was thrilled. As someone who has made musicals, world premieres, family programming, and presentations from around the globe. theatre in an array of found and site-sympathetic The work is enjoyed by 225,000 audience members annually, with one in four under the age of spaces, including pubs, shops, piers, beneath eighteen. Chicago Shakespeare is the city’s leading producer of international work, and touring flyovers, and one time inside a de-sanctified church, its own productions across five continents has garnered multiple accolades, including the putting theatre on in pubs around Ireland felt like a prestigious Laurence Olivier Award. Emblematic of its role as a global theater, the company sort of homecoming. I suspect every theatre director spearheaded Shakespeare 400 Chicago, celebrating Shakespeare’s legacy in a citywide, based outside of Dublin has had a production of yearlong international arts and culture festival, which engaged 1.1 million people. The Theater’s some sort or another perform in a pub, so why did nationally acclaimed arts in literacy programs support the work of English and drama teachers, this feel different? and bring Shakespeare to life on stage for tens of thousands of their students each school year. -

The Montclarion, April 22, 1970

Montclair State University Montclair State University Digital Commons The onM tclarion Student Newspapers 4-22-1970 The onM tclarion, April 22, 1970 The onM tclarion Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/montclarion Recommended Citation The onM tclarion, "The onM tclarion, April 22, 1970" (1970). The Montclarion. 136. https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/montclarion/136 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Montclair State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The onM tclarion by an authorized administrator of Montclair State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Montclarion Serving the College Community Since 1928, Wed., April 22, 1970. Voi. 44, No. 32 MONTCLAIR STATE COLLEGE, MONTCLAIR. N.J. 07043. Grajev/ski Gets Veep Post; Sova Reelected SEE STORY PAGE 3. Newly-elected SGA president Tom Benitz gets a congratulatory kiss trom an excited coed. HE’S A WINNER Staff Photo by Morey X. Antebi. Today’s Earth Day — Save Our World Page 2. MONTCLA R ION. Wed.. April 22. 1970. Here’s Hoping Earth Day Will Avoid Doomsday By Donald S. Rosser That's a description of Special To The Montclarion. "ecology," a subject that is Some people think man is receiving new attention in the on the brink of exterminating public schools. Say Dr. Allen: himself. Because few people "Man is an inseparable part of as well as in London and Los would welcome human a system composed of men, Angeles in 1952. Air pollution extinction, today has been cu ltu re and the natural can also damage the health. -

Book Auction Catalogue

1. 4 Postal Guide Books Incl. Ainmneacha Gaeilge Na Mbail Le Poist 2. The Scallop (Studies Of A Shell And Its Influence On Humankind) + A Shell Book 3. 2 Irish Lace Journals, Embroidery Design Book + A Lace Sampler 4. Box Of Pamphlets + Brochures 5. Lot Travel + Other Interest 6. 4 Old Photograph Albums 7. Taylor: The Origin Of The Aryans + Wilson: English Apprenticeship 1603-1763 8. 2 Scrap Albums 1912 And Recipies 9. Victorian Wildflowers Photograph Album + Another 10. 2 Photography Books 1902 + 1903 11. Wild Wealth – Sears, Becker, Poetker + Forbeg 12. 3 Illustrated London News – Cornation 1937, Silver Jubilee 1910-1935, Her Magesty’s Glorious Jubilee 1897 13. 3 Meath Football Champions Posters 14. Box Of Books – History Of The Times etc 15. Box Of Books Incl. 3 Vols Wycliff’s Opinion By Vaughan 16. Box Books Incl. 2 Vols Augustus John Michael Holroyd 17. Works Of Canon Sheehan In Uniform Binding – 9 Vols 18. Brendan Behan – Moving Out 1967 1st Ed. + 3 Other Behan Items 19. Thomas Rowlandson – The English Dance Of Death 1903. 2 Vols. Colour Plates 20. W.B. Yeats. Sophocle’s King Oedipis 1925 1st Edition, Yeats – The Celtic Twilight 1912 And Yeats Introduction To Gitanjali 21. Flann O’Brien – The Best Of Myles 1968 1st Ed. The Hard Life 1973 And An Illustrated Biography 1987 (3) 22. Ancient Laws Of Ireland – Senchus Mor. 1865/1879. 4 Vols With Coloured Lithographs 23. Lot Of Books Incl. London Museum Medieval Catalogue 24. Lot Of Irish Literature Incl. Irish Literature And Drama. Stephen Gwynn A Literary History Of Ireland, Douglas Hyde etc 25. -

Copyright by Alexandra Lynn Barron 2005

Copyright By Alexandra Lynn Barron 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Alexandra Lynn Barron certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Postcolonial Unions: The Queer National Romance in Film and Literature Committee: __________________ Lisa Moore, Supervisor __________________ Mia Carter __________________ Janet Staiger __________________ Ann Cvetkovich __________________ Neville Hoad Postcolonial Unions: The Queer National Romance in Film and Literature by Alexandra Lynn Barron, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2005 For my mother who taught me to read and made sure that I loved it. Acknowledgments It is odd to have a single name on a project that has benefited from so many people’s contributions. I have been writing these acknowledgments in my head since I began the project, but now that the time is here to set them down I am a bit at a loss as to how to convey how truly indebted I am. To start, I would like to thank Sabrina Barton, Mia Carter, Ann Cvetkovich, Neville Hoad, and Janet Staiger for their insights, for their encouragement, and for teaching me what it means to be an engaged scholar. Lisa Moore has been a teacher, a writing coach, a cheerleader, and a friend. She approached my work with a combination of rigor and compassion that made this dissertation far better than it would have been without her guidance. I could not have done this without her. -

About the Artists

Fishamble: The New Play Company presents Swing Written by Steve Blount, Peter Daly, Gavin Kostick and Janet Moran Performed by Arthur Riordan and Gene Rooney ABOUT THE ARTISTS: Arthur Riordan - Performer (Joe): is a founder member of Rough Magic and has appeared in many of their productions, including Peer Gynt, Improbable Frequency, Solemn Mass for a Full Moon in Summer, and more. He has also worked with the Abbey & Peacock Theatre, Gaiety Theatre, Corcadorca, Pan Pan, Druid, The Corn Exchange, Bedrock Productions, Red Kettle, Fishamble, Project, Bewleys Café Theatre and most recently, with Livin’ Dred, in their production of The Kings Of The Kilburn High Road. Film and TV appearances include Out Of Here, Ripper Street, The Clinic, Fair City, Refuge, Borstal Boy, Rat, Pitch’n’Putt with Joyce’n’Beckett, My Dinner With Oswald, and more. Gene Rooney - Performer (May): has performed on almost every stage in Ireland in over 40 productions. Some of these include: Buck Jones and the Bodysnatchers (Dublin Theatre Festival), The Colleen Bawn Trials (Limerick City of Culture), Pigtown, The Taming of the Shrew, Lovers (Island Theatre Company), The Importance of Being Earnest (Gúna Nua), Our Father (With an F Productions), How I Learned to Drive (The Lyric, Belfast), I ❤Alice ❤ I (Hot for Theatre), TV and film work includes Moone Boy, Stella Days, The Sea, Hideaways, Killinaskully, Botched, The Last Furlong and The Clinic Janet Moran - Writer Janet’s stage work includes Juno and the Paycock (National Theatre, London/Abbey Theatre coproduction), Shibari, Translations, No Romance, The Recruiting Officer, The Cherry orchard, She Stoops to Conquer, Communion, The Barbaric Comedies, The Well of the Saints and The Hostage (all at the Abbey Theatre). -

The Novel and the Short Story in Ireland

The Novel and the Short Story in Ireland: Readership, Society and Fiction, 1922-1965. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Anthony Halpen April 2016 Anthony Halpen Institute of Irish Studies The University of Liverpool 27.03.2016 i ABSTRACT The Novel and the Short Story in Ireland: Readership, Society and Fiction, 1922-1965. Anthony Halpen, The Institute of Irish Studies, The University of Liverpool. This thesis considers the novel and the short story in the decades following the achievement of Irish independence from Britain in 1922. During these years, many Irish practitioners of the short story achieved both national and international acclaim, such that 'the Irish Short Story' was recognised as virtually a discrete genre. Writers and critics debated why Irish fiction-writers could have such success in the short story, but not similar success with their novels. Henry James had noticed a similar situation in the United States of America in the early nineteenth century. James decided the problem was that America's society was still forming - that the society was too 'thin' to support successful novel-writing. Irish writers and critics applied his arguments to the newly-independent Ireland, concluding that Irish society was indeed the explanation. Irish society was depicted as so unstructured and fragmented that it was inimical to the novel but nurtured the short story. Ireland was described variously: "broken and insecure" (Colm Tóibín), "often bigoted, cowardly, philistine and spiritually crippled" (John McGahern) and marked by "inward-looking stagnation" (Dermot Bolger).