Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Derek Paget

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Littlewood Education Pack in Association with Essentialdrama.Com Joan Littlewood Education Pack

in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan LittlEWOOD Education pack in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan Littlewood Education PAck Biography 2 Artistic INtentions 5 Key Collaborators 7 Influences 9 Context 11 Productions 14 Working Method 26 Text Phil Cleaves Nadine Holdsworth Theatre Recipe 29 Design Phil Cleaves Further Reading 30 Cover Image Credit PA Image Joan LIttlewood: Education pack 1 Biography Early Life of her life. Whilst at RADA she also had Joan Littlewood was born on 6th October continued success performing 1914 in South-West London. She was part Shakespeare. She won a prize for her of a working class family that were good at verse speaking and the judge of that school but they left at the age of twelve to competition, Archie Harding, cast her as get work. Joan was different, at twelve she Cleopatra in Scenes from Shakespeare received a scholarship to a local Catholic for BBC a overseas radio broadcast. That convent school. Her place at school meant proved to be one of the few successes that she didn't ft in with the rest of her during her time at RADA and after a term family, whilst her background left her as an she dropped out early in 1933. But the outsider at school. Despite being a misft, connection she made with Harding would Littlewood found her feet and discovered prove particularly infuential and life- her passion. She fell in love with the changing. theatre after a trip to see John Gielgud playing Hamlet at the Old Vic. Walking to Find Work Littlewood had enjoyed a summer in Paris It had me on the edge of my when she was sixteen and decided to seat all afternoon. -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

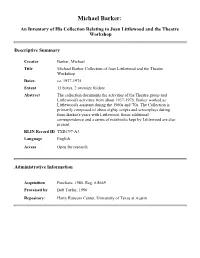

Michael Barker

Michael Barker: An Inventory of His Collection Relating to Joan Littlewood and the Theatre Workshop Descriptive Summary Creator Barker, Michael Title Michael Barker Collection of Joan Littlewood and the Theatre Workshop Dates: ca. 1937-1975 Extent 15 boxes, 2 oversize folders Abstract The collection documents the activities of the Theatre group and Littlewood's activities from about 1937-1975. Barker worked as Littlewood's assistant during the 1960s and '70s. The Collection is primarily composed of about eighty scripts and screenplays dating from Barker's years with Littlewood. Some additional correspondence and a series of notebooks kept by Littlewood are also present. RLIN Record ID TXRC97-A3 Language English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1980, Reg. # 8669 Processed by Bob Taylor, 1996 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Barker, Michael Biographical Sketch Michael Barker, who assembled this collection of Joan Littlewood materials, worked with her in the 1960s and '70s as an assistant and was involved both in theatrical endeavors as well as the street theater ventures. Joan Maud Littlewood was born into a working-class family in London's East End in October 1914. Early demonstrating an acute mind and an artistic bent she won scholarships to a Catholic school and then to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. Quickly realizing that RADA was neither philosophically nor socially congenial, she departed to study art. In 1934--still short of twenty years of age--she arrived in Manchester to work for the BBC. Littlewood soon met Jimmy Miller (Ewan MacColl) and collaborated with him in the Theatre of Action, a leftist drama group. -

Nine Night at the Trafalgar Studios

7 September 2018 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S PRODUCTION OF NINE NIGHT AT THE TRAFALGAR STUDIOS NINE NIGHT by Natasha Gordon Trafalgar Studios 1 December 2018 – 9 February 2019, Press night 6 December The National Theatre have today announced the full cast for Nine Night, Natasha Gordon’s critically acclaimed play which will transfer from the National Theatre to the Trafalgar Studios on 1 December 2018 (press night 6 December) in a co-production with Trafalgar Theatre Productions. Natasha Gordon will take the role of Lorraine in her debut play, for which she has recently been nominated for the Best Writer Award in The Stage newspaper’s ‘Debut Awards’. She is joined by Oliver Alvin-Wilson (Robert), Michelle Greenidge (Trudy), also nominated in the Stage Awards for Best West End Debut, Hattie Ladbury (Sophie), Rebekah Murrell (Anita) and Cecilia Noble (Aunt Maggie) who return to their celebrated NT roles, and Karl Collins (Uncle Vince) who completes the West End cast. Directed by Roy Alexander Weise (The Mountaintop), Nine Night is a touching and exuberantly funny exploration of the rituals of family. Gloria is gravely sick. When her time comes, the celebration begins; the traditional Jamaican Nine Night Wake. But for Gloria’s children and grandchildren, marking her death with a party that lasts over a week is a test. Nine rum-fuelled nights of music, food, storytelling and laughter – and an endless parade of mourners. The production is designed by Rajha Shakiry, with lighting design by Paule Constable, sound design by George Dennis, movement direction by Shelley Maxwell, company voice work and dialect coaching by Hazel Holder, and the Resident Director is Jade Lewis. -

Trafalgar Entertainment Launch Release 22-06-2017

22nd June 2017 HOWARD PANTER AND ROSEMARY SQUIRE LAUNCH THEIR NEW VENTURE TRAFALGAR ENTERTAINMENT GROUP WITH THE ACQUISITION OF TRAFALGAR RELEASING (FORMERLY OPERATING AS PICTUREHOUSE ENTERTAINMENT) AND THE PURCHASE OF TRAFALGAR STUDIOS Sir Howard Panter and Rosemary Squire OBE announced today the acquisition of Trafalgar Releasing (formerly operating as Picturehouse Entertainment), an award winning, market- leader in global event distribution, to be known as Trafalgar Releasing. This multi million purchase coincides with the completed acquisition by the theatrical impresarios of London’s Trafalgar Studios, with its two London Theatres. Trafalgar Entertainment’s next theatre production at Trafalgar Studios will star Tony and Emmy Award winning Stockard Channing in Apologia “Sharp, funny, wise & humane” (Daily Telegraph) written by Alexi Kaye Campbell, and directed by Jamie Lloyd. It will preview at Trafalgar Studios from 29 July 2017. Among other productions Howard Panter will also continue to produce The Rocky Horror show globally, including new productions in New York, Germany and Australia. Trafalgar Releasing works with some of the world’s most renowned arts institutions, distributing high-profile live content to cinemas in the UK and around the world from the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Bolshoi Ballet, Glyndebourne, the National Theatre, the Metropolitan Opera and the Royal Opera House. Recent Trafalgar Releasing announcements have included David Gilmour Live at Pompeii screening in approximately 2000 cinemas around the world, Donmar presents Julius Caesar, the first part of Phyllida Lloyd’s Shakespeare Trilogy and Alone in Berlin Live from IWM London, a preview featuring Emma Thompson followed by a lively and inspiring discussion exploring the themes of the film. -

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Embarks on a Third Uk and Ireland Tour This Autumn

3 March 2020 THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S INTERNATIONALLY-ACCLAIMED PRODUCTION OF THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME EMBARKS ON A THIRD UK AND IRELAND TOUR THIS AUTUMN • TOUR INCLUDES A LIMITED SEVEN WEEK RUN AT THE TROUBADOUR WEMBLEY PARK THEATRE FROM WEDNESDAY 18 NOVEMBER 2020 Back by popular demand, the Olivier and Tony Award®-winning production of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time will tour the UK and Ireland this Autumn. Launching at The Lowry, Salford, Curious Incident will then go on to visit to Sunderland, Bristol, Birmingham, Plymouth, Southampton, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Dublin, Belfast, Nottingham and Oxford, with further venues to be announced. Curious Incident will also play for a limited run in London at Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre in Brent - London Borough of Culture 2020 - following the acclaimed run of War Horse in 2019. Curious Incident has been seen by more than five million people worldwide, including two UK tours, two West End runs, a Broadway transfer, tours to the Netherlands, Canada, Hong Kong, Singapore, China, Australia and 30 cities across the USA. Curious Incident is the winner of seven Olivier Awards including Best New Play, Best Director, Best Design, Best Lighting Design and Best Sound Design. Following its New York premiere in September 2014, it became the longest-running play on Broadway in over a decade, winning five Tony Awards® including Best Play, six Drama Desk Awards including Outstanding Play, five Outer Critics Circle Awards including Outstanding New Broadway Play and the Drama League Award for Outstanding Production of a Broadway or Off Broadway Play. -

New Appointments at Trafalgar Entertainment Group Bolster Company’S Expansion Plans

PRESS RELEASE 01/11/2018 NEW APPOINTMENTS AT TRAFALGAR ENTERTAINMENT GROUP BOLSTER COMPANY’S EXPANSION PLANS Sir Howard Panter and Dame Rosemary Squire have made two major appointments as part of their planned expansion of Trafalgar Entertainment Group (TEG). Tim McFarlane has joined the TEG senior management team as Executive Chairman of Trafalgar Entertainment Asia-Pacific Pty Limited and Andrew Hill has been appointed as Business Affairs Director of Trafalgar Entertainment Group. Tim commenced his role earlier this autumn and is based in Sydney, whilst Andrew commences work on 1 November at TEG’s London office on The Strand. Both Tim and Andrew have previously worked with Howard and Rosemary as they built one of the world’s largest and most successful live theatre businesses, the Ambassador Theatre Group. At TEG, Tim is already working on various Australian projects, and he will be driving TEG’s international strategy to build and strengthen relationships and partnerships in the Asia Pacific region. Andrew will be responsible for overseeing the company’s planned future growth, acquisitions and business development. Tim McFarlane, said: “To work with Sir Howard and Dame Rosemary pursuing theatres and productions for Australia and Asia Pacific is to work with the best people in the business. I’m absolutely delighted.” Andrew Hill, said: “I have worked alongside Rosemary and Howard in an advisory capacity on a number of their transformative acquisitions, and have always admired their tenacity, insight and vision. I am very much looking forward to supporting them in the future expansion and development of Trafalgar Entertainment Group.” Executive Chair and Joint CEO of TEG, Dame Rosemary Squire, said: “These are two really exciting appointments for Trafalgar Entertainment Group as we continue to invest in the company’s future and build our executive team. -

David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane Eastern European, Scandinavian, Location: London Appearance: White Height: 5'11" (180cm) Other: Equity Weight: 13st. 6lb. (85kg) Eye Colour: Blue Playing Age: 51 - 65 years Hair Length: Mid Length Stage Stage, Cardinal Von Galen, All Our Children, Jermyn Street Theatre, Stephen Unwin Stage, Antigonus, The Winter's Tale, Globe Theatre, Michael Longhurst Stage, Lord Clifford Allen, Taken At Midnight, Chichester Festival Theatre & Haymarket Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Earl of Caversham, An Ideal Husband, Gate Theatre, Ethan McSweeney Stage, Sir George Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Gate Theatre, Dublin, Patrick Mason Stage, Selwyn Lloyd, A Marvellous Year For Plums, Chichester Festival Theatre, Philip Franks Stage, Serebryakov, Uncle Vanya, The Print Room, Lucy Bailey Stage, King Henry, Henry IV Parts 1&2, Theatre Royal Bath & Tour, Sir Peter Hall Stage, Anthony Blunt, Single Spies, The Watermill, Jamie Glover Stage, Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Theatre Royal Bath & West End, Michael Rudman Stage, President of the Court, For King & Country, Matthew Byam shaw, Tristram Powell Stage, Clive, The Circle, Chichester Festival Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Ralph Nickleby, Nicholas Nickleby, Chichester Festival Theatre,Gielgud , and Toronto, Philip Franks, Jonathan Church Stage, Wilfred Cedar, For Services Rendered, The Watermill -

Lamda.Ac.Uk Review of the Year 1 WELCOME

REVIEW OF THE YEAR 17-18 lamda.ac.uk Review of the Year 1 WELCOME Introduction from our Chairman and Principal. This year we have been focussing on: 2017-18 has been a year of rapid development and growth for LAMDA Our students and alumni continue to be prolific across film, theatre and television • Utilising our new fully-accessible building to its maximum potential and capacity. production, both nationally and internationally; our new building enables us to deliver • Progressing our journey to become an independent Higher Education Provider with degree gold standard facilities in a fully accessible environment; and our progress towards awarding powers. registration as a world-leading Higher Education Provider continues apace. • Creating additional learning opportunities for students through new collaborations with other arts LAMDA Examinations continues to flourish with 2017/18 yielding its highest number of entrants to organisations and corporate partners. date, enabling young people across the globe to become confident and creative communicators. • Widening access to ensure that any potential student has the opportunity to enrol with LAMDA. We hope you enjoy reading about our year. • Extending our global reach through the expansion of LAMDA Examinations. Rt. Hon. Shaun Woodward Joanna Read Chairman Principal lamda.ac.uk Review of the Year 2 OUR PURPOSE Our mission is to seek out, train and empower exceptional dramatic artists and technicians of every generation, so they can make the most extraordinary impact across the world through their work. Our examinations in drama and communications inspire people to become confident, authentic communicators and discover their own voice. Our vision is to be a diverse and engaged institution in every sense, shaping the future of the dramatic arts and creative industries, and fulfilling a vital role in the continuing artistic, cultural and economic success of the UK. -

Ewan Maccoll, “The Brilliant Young Scots Dramatist”: Regional Myth-Making and Theatre Workshop

Ewan MacColl, “the brilliant young Scots dramatist”: Regional myth-making and Theatre Workshop Claire Warden, University of Lincoln Moving to London In 1952, Theatre Workshop had a decision to make. There was a growing sense that the company needed a permanent home (Goorney 1981: 85) and, rather than touring plays, to commit to a particular community. As they created their politically challenging, artistically vibrant work, group members sought a geographical stability, a chance to respond to and become part of a particular location. And, more than this, the group wanted a building to house them after many years of rented accommodation, draughty halls and borrowed rooms. Ewan MacColl and Joan Littlewood’s company had been founded in Manchester in 1945, aiming to create confrontational plays for the post-war audience. But the company actually had its origins in a number of pre-War Mancunian experiments. Beginning as the agit-prop Red Megaphones in 1931, MacColl and some local friends performed short sketches with songs, often discussing particularly Lancastrian issues, such as loom strikes and local unemployment. With the arrival of Littlewood, the group was transformed into, first, Theatre of Action (1934) and then Theatre Union (1936). Littlewood and MacColl collaborated well, with the former bringing some theatrical expertise from her brief spell at RADA (Holdsworth 2006: 45) (though, interestingly in light of the argument here, this experience largely taught Littlewood what she did not want in the theatre!) and the latter his experience of performing on the streets of Salford. Even in the early days of Theatre Workshop, as the company sought to create a formally innovative and thematically agitational theatre, the founders brought their own experiences of the Capital and the regions, of the centre and periphery. -

Special Trees Project

Spring 2015 1 News from Loughton Town Council Spring 2015 No 68 Special trees project WE ARE delighted to announce one where we, and the people the launch of the “Loughton we care about, can be safe, Special Trees” project to find happy and healthy. An attractive which trees matter most to the environment helps us to live people of our town. richer lives in a whole variety of Residents are invited to ways. A big part of that is having nominate their favourite local trees and not just anywhere and trees – those which have a anyhow, but the right trees in the personal connection for them right places. and to give us the reasons why Sometimes these trees are they matter particularly to you. just functional - say helping These can be special trees in screen off an unattractive view public spaces or private gardens or providing shelter for birds, or and, of course, we won’t forget other wildlife. Trees can also be the importance of the owners! special in their own right. This We want tree owners to be may be because of their great proud of their trees and we think age – Loughton has many trees that to know that your trees are dating from 1760 or even earlier, special will make most people which could reasonably be proud. We will try to make sure described as living monuments. you have extra help and advice if Other trees are special to us in you should ever need it. more personal ways because This venture follows on from of their size, how they mark a the Loughton Community Tree particular location or frame a Strategy and from the Favourite view, because of their links to Trees project to find the 50 most special people or events or, special trees for the Epping not least, purely for their great Forest district as a whole. -

TESIS DOCTORAL Luis Martínez Becerra RECEPCIÓN DEL

TESIS DOCTORAL Luis Martínez Becerra RECEPCIÓN DEL TEATRO DE ESTADOS UNIDOS EN ESPAÑA A TRAVÉS DEL DIARIO EL PAIS: 1976-2016 Dirigida por los doctores Miguel Juan Gronow Smith y Juan Ignacio Guijarro González Departamento de Filología Inglesa (Literatura Inglesa y Norteamericana) Facultad de Filología Universidad de Sevilla Sevilla 2021 Agradecimientos En esta tarea enorme, desarrollada a lo largo de más de cinco años de trabajo y alguno más de recopilación previa de datos, nos hemos topado con no pocos obstáculos, sorteados con gran esfuerzo y dedicación constante. Podría ser muy larga la lista de personas e instituciones a las que le debemos agradecimiento por su contribución de algún u otro modo a esta Tesis. Afortunadamente, hemos recibido el apoyo de allegados, familiares y amigos, que han confiado siempre en nuestro trabajo y alentado su conclusión. Algunas ya no están entre nosotros y es a las que queremos dedicárselo en primer lugar. Vaya a continuación nuestro agradecimiento muy especial a los directores de esta Tesis, los doctores Michael Gronow y Juan Ignacio Guijarro, del Departamento de Filología Inglesa (Literatura Inglesa y Norteamericana) de esta Facultad, que nos han acompañado en su elaboración y revisado con gran interés todos los bocetos de este trabajo. Gracias también por vuestro ánimo y amistad. De paso quisiéramos extender el agradecimiento al Departamento y al Programa del Doctorado que nos han acogido y brindado esta oportunidad. Asimismo, queríamos agradecer la colaboración del Centro de Documentación Teatral del Ministerio de Cultura y de su diligente personal por haber puesto todo su material a nuestra disposición tanto en su sede como a través de todos los medios de los dispone, que no son pocos.