An Instruction Set and Microarchitecture for Instruction Level Distributed Processing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Intel® Core™ Microarchitecture Setting New Standards for Energy-Efficient Performance

White Paper Inside Intel® Core™ Microarchitecture Setting New Standards for Energy-Efficient Performance Ofri Wechsler Intel Fellow, Mobility Group Director, Mobility Microprocessor Architecture Intel Corporation White Paper Inside Intel®Core™ Microarchitecture Introduction Introduction 2 The Intel® Core™ microarchitecture is a new foundation for Intel®Core™ Microarchitecture Design Goals 3 Intel® architecture-based desktop, mobile, and mainstream server multi-core processors. This state-of-the-art multi-core optimized Delivering Energy-Efficient Performance 4 and power-efficient microarchitecture is designed to deliver Intel®Core™ Microarchitecture Innovations 5 increased performance and performance-per-watt—thus increasing Intel® Wide Dynamic Execution 6 overall energy efficiency. This new microarchitecture extends the energy efficient philosophy first delivered in Intel's mobile Intel® Intelligent Power Capability 8 microarchitecture found in the Intel® Pentium® M processor, and Intel® Advanced Smart Cache 8 greatly enhances it with many new and leading edge microar- Intel® Smart Memory Access 9 chitectural innovations as well as existing Intel NetBurst® microarchitecture features. What’s more, it incorporates many Intel® Advanced Digital Media Boost 10 new and significant innovations designed to optimize the Intel®Core™ Microarchitecture and Software 11 power, performance, and scalability of multi-core processors. Summary 12 The Intel Core microarchitecture shows Intel’s continued Learn More 12 innovation by delivering both greater energy efficiency Author Biographies 12 and compute capability required for the new workloads and usage models now making their way across computing. With its higher performance and low power, the new Intel Core microarchitecture will be the basis for many new solutions and form factors. In the home, these include higher performing, ultra-quiet, sleek and low-power computer designs, and new advances in more sophisticated, user-friendly entertainment systems. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76992-1 - Microprocessor Architecture: From Simple Pipelines to Chip Multiprocessors Jean-Loup Baer Excerpt More information 1 Introduction Modern computer systems built from the most sophisticated microprocessors and extensive memory hierarchies achieve their high performance through a combina- tion of dramatic improvements in technology and advances in computer architec- ture. Advances in technology have resulted in exponential growth rates in raw speed (i.e., clock frequency) and in the amount of logic (number of transistors) that can be put on a chip. Computer architects have exploited these factors in order to further enhance performance using architectural techniques, which are the main subject of this book. Microprocessors are over 30 years old: the Intel 4004 was introduced in 1971. The functionality of the 4004 compared to that of the mainframes of that period (for example, the IBM System/370) was minuscule. Today, just over thirty years later, workstations powered by engines such as (in alphabetical order and without specific processor numbers) the AMD Athlon, IBM PowerPC, Intel Pentium, and Sun UltraSPARC can rival or surpass in both performance and functionality the few remaining mainframes and at a much lower cost. Servers and supercomputers are more often than not made up of collections of microprocessor systems. It would be wrong to assume, though, that the three tenets that computer archi- tects have followed, namely pipelining, parallelism, and the principle of locality, were discovered with the birth of microprocessors. They were all at the basis of the design of previous (super)computers. The advances in technology made their implementa- tions more practical and spurred further refinements. -

Instruction Latencies and Throughput for AMD and Intel X86 Processors

Instruction latencies and throughput for AMD and Intel x86 processors Torbj¨ornGranlund 2019-08-02 09:05Z Copyright Torbj¨ornGranlund 2005{2019. Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium, provided this notice is preserved. This report is work-in-progress. A newer version might be available here: https://gmplib.org/~tege/x86-timing.pdf In this short report we present latency and throughput data for various x86 processors. We only present data on integer operations. The data on integer MMX and SSE2 instructions is currently limited. We might present more complete data in the future, if there is enough interest. There are several reasons for presenting this report: 1. Intel's published data were in the past incomplete and full of errors. 2. Intel did not publish any data for 64-bit operations. 3. To allow straightforward comparison of an important aspect of AMD and Intel pipelines. The here presented data is the result of extensive timing tests. While we have made an effort to make sure the data is accurate, the reader is cautioned that some errors might have crept in. 1 Nomenclature and notation LNN means latency for NN-bit operation.TNN means throughput for NN-bit operation. The term throughput is used to mean number of instructions per cycle of this type that can be sustained. That implies that more throughput is better, which is consistent with how most people understand the term. Intel use that same term in the exact opposite meaning in their manuals. The notation "P6 0-E", "P4 F0", etc, are used to save table header space. -

POWER-AWARE MICROARCHITECTURE: Design and Modeling Challenges for Next-Generation Microprocessors

POWER-AWARE MICROARCHITECTURE: Design and Modeling Challenges for Next-Generation Microprocessors THE ABILITY TO ESTIMATE POWER CONSUMPTION DURING EARLY-STAGE DEFINITION AND TRADE-OFF STUDIES IS A KEY NEW METHODOLOGY ENHANCEMENT. OPPORTUNITIES FOR SAVING POWER CAN BE EXPOSED VIA MICROARCHITECTURE-LEVEL MODELING, PARTICULARLY THROUGH CLOCK- GATING AND DYNAMIC ADAPTATION. Power dissipation limits have Thus far, most of the work done in the area David M. Brooks emerged as a major constraint in the design of high-level power estimation has been focused of microprocessors. At the low end of the per- at the register-transfer-level (RTL) description Pradip Bose formance spectrum, namely in the world of in the processor design flow. Only recently have handheld and portable devices or systems, we seen a surge of interest in estimating power Stanley E. Schuster power has always dominated over perfor- at the microarchitecture definition stage, and mance (execution time) as the primary design specific work on power-efficient microarchi- Hans Jacobson issue. Battery life and system cost constraints tecture design has been reported.2-8 drive the design team to consider power over Here, we describe the approach of using Prabhakar N. Kudva performance in such a scenario. energy-enabled performance simulators in Increasingly, however, power is also a key early design. We examine some of the emerg- Alper Buyuktosunoglu design issue in the workstation and server mar- ing paradigms in processor design and com- kets (see Gowan et al.)1 In this high-end arena ment on their inherent power-performance John-David Wellman the increasing microarchitectural complexities, characteristics. clock frequencies, and die sizes push the chip- Victor Zyuban level—and hence the system-level—power Power-performance efficiency consumption to such levels that traditionally See the “Power-performance fundamentals” Manish Gupta air-cooled multiprocessor server boxes may box. -

Hardware Architecture

Hardware Architecture Components Computing Infrastructure Components Servers Clients LAN & WLAN Internet Connectivity Computation Software Storage Backup Integration is the Key ! Security Data Network Management Computer Today’s Computer Computer Model: Von Neumann Architecture Computer Model Input: keyboard, mouse, scanner, punch cards Processing: CPU executes the computer program Output: monitor, printer, fax machine Storage: hard drive, optical media, diskettes, magnetic tape Von Neumann architecture - Wiki Article (15 min YouTube Video) Components Computer Components Components Computer Components CPU Memory Hard Disk Mother Board CD/DVD Drives Adaptors Power Supply Display Keyboard Mouse Network Interface I/O ports CPU CPU CPU – Central Processing Unit (Microprocessor) consists of three parts: Control Unit • Execute programs/instructions: the machine language • Move data from one memory location to another • Communicate between other parts of a PC Arithmetic Logic Unit • Arithmetic operations: add, subtract, multiply, divide • Logic operations: and, or, xor • Floating point operations: real number manipulation Registers CPU Processor Architecture See How the CPU Works In One Lesson (20 min YouTube Video) CPU CPU CPU speed is influenced by several factors: Chip Manufacturing Technology: nm (2002: 130 nm, 2004: 90nm, 2006: 65 nm, 2008: 45nm, 2010:32nm, Latest is 22nm) Clock speed: Gigahertz (Typical : 2 – 3 GHz, Maximum 5.5 GHz) Front Side Bus: MHz (Typical: 1333MHz , 1666MHz) Word size : 32-bit or 64-bit word sizes Cache: Level 1 (64 KB per core), Level 2 (256 KB per core) caches on die. Now Level 3 (2 MB to 8 MB shared) cache also on die Instruction set size: X86 (CISC), RISC Microarchitecture: CPU Internal Architecture (Ivy Bridge, Haswell) Single Core/Multi Core Multi Threading Hyper Threading vs. -

Microcontroller Serial Interfaces

Microcontroller Serial Interfaces Dr. Francesco Conti [email protected] Microcontroller System Architecture Each MCU (micro-controller unit) is characterized by: • Microprocessor • 8,16,32 bit architecture • Usually “simple” in-order microarchitecture, no FPU Example: STM32F101 MCU Microcontroller System Architecture Each MCU (micro-controller unit) is characterized by: • Microprocessor • 8,16,32 bit architecture • Usually “simple” in-order microarchitecture, no FPU • Memory • RAM (from 512B to 256kB) • FLASH (from 512B to 1MB) Example: STM32F101 MCU Microcontroller System Architecture Each MCU (micro-controller unit) is characterized by: • Microprocessor • 8,16,32 bit architecture • Usually “simple” in-order microarchitecture, no FPU • Memory • RAM (from 512B to 256kB) • FLASH (from 512B to 1MB) • Peripherals • DMA • Timer • Interfaces • Digital Interfaces • Analog Timer DMAs Example: STM32F101 MCU Microcontroller System Architecture Each MCU (micro-controller unit) is characterized by: • Microprocessor • 8,16,32 bit architecture • Usually “simple” in-order microarchitecture, no FPU • Memory • RAM (from 512B to 256kB) • FLASH (from 512B to 1MB) • Peripherals • DMA • Timer • Interfaces • Digital • Analog • Interconnect Example: STM32F101 MCU • AHB system bus (ARM-based MCUs) • APB peripheral bus (ARM-based MCUs) Microcontroller System Architecture Each MCU (micro-controller unit) is characterized by: • Microprocessor • 8,16,32 bit architecture • Usually “simple” in-order microarchitecture, no FPU • Memory • RAM (from 512B to 256kB) • FLASH -

Exam 1 Solutions

Midterm Exam ECE 741 – Advanced Computer Architecture, Spring 2009 Instructor: Onur Mutlu TAs: Michael Papamichael, Theodoros Strigkos, Evangelos Vlachos February 25, 2009 EXAM 1 SOLUTIONS Problem Points Score 1 40 2 20 3 15 4 20 5 25 6 20 7 (bonus) 15 Total 140+15 • This is a closed book midterm. You are allowed to have only two letter-sized cheat sheets. • No electronic devices may be used. • This exam lasts 1 hour 50 minutes. • If you make a mess, clearly indicate your final answer. • For questions requiring brief answers, please provide brief answers. Do not write an essay. You can be penalized for verbosity. • Please show your work when needed. We cannot give you partial credit if you do not clearly show how you arrive at a numerical answer. • Please write your name on every sheet. EXAM 1 SOLUTIONS Problem 1 (Short answers – 40 points) i. (3 points) A cache has the block size equal to the word length. What property of program behavior, which usually contributes to higher performance if we use a cache, does not help the performance if we use THIS cache? Spatial locality ii. (3 points) Pipelining increases the performance of a processor if the pipeline can be kept full with useful instructions. Two reasons that often prevent the pipeline from staying full with useful instructions are (in two words each): Data dependencies Control dependencies iii. (3 points) The reference bit (sometimes called “access” bit) in a PTE (Page Table Entry) is used for what purpose? Page replacement The similar function is performed by what bit or bits in a cache’s tag store entry? Replacement policy bits (e.g. -

Trends in Processor Architecture

A. González Trends in Processor Architecture Trends in Processor Architecture Antonio González Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain 1. Past Trends Processors have undergone a tremendous evolution throughout their history. A key milestone in this evolution was the introduction of the microprocessor, term that refers to a processor that is implemented in a single chip. The first microprocessor was introduced by Intel under the name of Intel 4004 in 1971. It contained about 2,300 transistors, was clocked at 740 KHz and delivered 92,000 instructions per second while dissipating around 0.5 watts. Since then, practically every year we have witnessed the launch of a new microprocessor, delivering significant performance improvements over previous ones. Some studies have estimated this growth to be exponential, in the order of about 50% per year, which results in a cumulative growth of over three orders of magnitude in a time span of two decades [12]. These improvements have been fueled by advances in the manufacturing process and innovations in processor architecture. According to several studies [4][6], both aspects contributed in a similar amount to the global gains. The manufacturing process technology has tried to follow the scaling recipe laid down by Robert N. Dennard in the early 1970s [7]. The basics of this technology scaling consists of reducing transistor dimensions by a factor of 30% every generation (typically 2 years) while keeping electric fields constant. The 30% scaling in the dimensions results in doubling the transistor density (doubling transistor density every two years was predicted in 1975 by Gordon Moore and is normally referred to as Moore’s Law [21][22]). -

Theoretical Peak FLOPS Per Instruction Set on Modern Intel Cpus

Theoretical Peak FLOPS per instruction set on modern Intel CPUs Romain Dolbeau Bull – Center for Excellence in Parallel Programming Email: [email protected] Abstract—It used to be that evaluating the theoretical and potentially multiple threads per core. Vector of peak performance of a CPU in FLOPS (floating point varying sizes. And more sophisticated instructions. operations per seconds) was merely a matter of multiplying Equation2 describes a more realistic view, that we the frequency by the number of floating-point instructions will explain in details in the rest of the paper, first per cycles. Today however, CPUs have features such as vectorization, fused multiply-add, hyper-threading or in general in sectionII and then for the specific “turbo” mode. In this paper, we look into this theoretical cases of Intel CPUs: first a simple one from the peak for recent full-featured Intel CPUs., taking into Nehalem/Westmere era in section III and then the account not only the simple absolute peak, but also the full complexity of the Haswell family in sectionIV. relevant instruction sets and encoding and the frequency A complement to this paper titled “Theoretical Peak scaling behavior of current Intel CPUs. FLOPS per instruction set on less conventional Revision 1.41, 2016/10/04 08:49:16 Index Terms—FLOPS hardware” [1] covers other computing devices. flop 9 I. INTRODUCTION > operation> High performance computing thrives on fast com- > > putations and high memory bandwidth. But before > operations => any code or even benchmark is run, the very first × micro − architecture instruction number to evaluate a system is the theoretical peak > > - how many floating-point operations the system > can theoretically execute in a given time. -

Reverse Engineering X86 Processor Microcode

Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz, Ruhr-University Bochum https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/presentation/koppe This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium August 16–18, 2017 • Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-1-931971-40-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz Ruhr-Universitat¨ Bochum Abstract hardware modifications [48]. Dedicated hardware units to counter bugs are imperfect [36, 49] and involve non- Microcode is an abstraction layer on top of the phys- negligible hardware costs [8]. The infamous Pentium fdiv ical components of a CPU and present in most general- bug [62] illustrated a clear economic need for field up- purpose CPUs today. In addition to facilitate complex and dates after deployment in order to turn off defective parts vast instruction sets, it also provides an update mechanism and patch erroneous behavior. Note that the implementa- that allows CPUs to be patched in-place without requiring tion of a modern processor involves millions of lines of any special hardware. While it is well-known that CPUs HDL code [55] and verification of functional correctness are regularly updated with this mechanism, very little is for such processors is still an unsolved problem [4, 29]. known about its inner workings given that microcode and the update mechanism are proprietary and have not been Since the 1970s, x86 processor manufacturers have throughly analyzed yet. -

Intel(R) Software Guard Extensions Developer Guide

Intel® Software Guard Extensions (Intel® SGX) Developer Guide Intel(R) Software Guard Extensions Developer Guide Legal Information No license (express or implied, by estoppel or otherwise) to any intellectual property rights is granted by this document. Intel disclaims all express and implied warranties, including without limitation, the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement, as well as any warranty arising from course of performance, course of dealing, or usage in trade. This document contains information on products, services and/or processes in development. All information provided here is subject to change without notice. Contact your Intel representative to obtain the latest forecast, sched- ule, specifications and roadmaps. The products and services described may contain defects or errors known as errata which may cause deviations from published specifications. Current char- acterized errata are available on request. Intel technologies features and benefits depend on system configuration and may require enabled hardware, software or service activation. Learn more at Intel.com, or from the OEM or retailer. Copies of documents which have an order number and are referenced in this document may be obtained by calling 1-800-548-4725 or by visiting www.in- tel.com/design/literature.htm. Intel, the Intel logo, Xeon, and Xeon Phi are trademarks of Intel Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. Optimization Notice Intel's compilers may or may not optimize to the same degree for non-Intel microprocessors for optimizations that are not unique to Intel micro- processors. These optimizations include SSE2, SSE3, and SSSE3 instruction sets and other optimizations. -

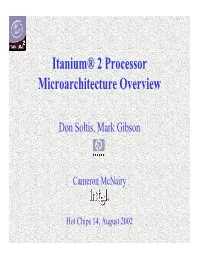

Itanium® 2 Processor Microarchitecture Overview

Itanium® 2 Processor Microarchitecture Overview Don Soltis, Mark Gibson Cameron McNairy Hot Chips 14, August 2002 Itanium® 2 Processor Overview 16KB16KB L1L1 I-cacheI-cache BranchBranch PredictPredict 2 bundles (128 bits each) InstrInstr 22 InstrInstr 11 InstrInstr 00 TemplateTemplate Issue up to 6 instructions to the 11 pipes FF FF M/AM/A M/AM/A M/AM/A M/AM/A I/AI/A I/AI/A BB BB BB 22 FMACsFMACs 66 ALUsALUs BranchBranch UnitUnit 6 Opnds 2 Preds 16KB16KB L1L1 D-cacheD-cache 12 Opnds 2 Results 4 Preds 6 Results 2 Loads, 2 Stores 6 Predicates 128 FP GPRs 128 Int GPRs Consumed 1 Predicate 3 Predicates 128 FP GPRs 4 Predicates 128 Int GPRs 12 Predicates Produced Block Diagram 64 Predicate Registers 4 Loads 64 Predicate Registers 2 Stores 256KB256KB L2L2 CacheCache 3MB3MB L3L3 CacheCache BusBus InterfaceInterface Hot Chips 14 Itanium® 2 Processor Overview EXEEXE DETDET WRBWRB IPGIPG ROTROT EXPEXP RENREN REGREG FP1FP1 FP2FP2 FP3FP3 FP4FP4 WRBWRB IPG: Instruction Pointer Generate, Instruction address to L1 I-cache ROT: Present 2 Instruction Bundles from L1 I-cache to dispersal hardware EXP: Disperse up to 6 instruction syllables from the 2 instruction bundles REN: Rename (or convert) virtual register IDs to physical register IDs REG: Register file read, or bypass results in flight as operands EXE: Execute integer instructions; generate results and predicates DET: Detect exceptions, traps, etc. FP1-4: Execute floating point instructions; generate results and predicates Main Execution Unit Pipeline WRB: Write back results to the register file