Van Gogh Museum Journal 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

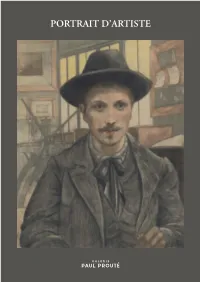

Portrait D'artiste

<--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------><- 15 mm -><--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------> 2020 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 74, rue de Seine — 75006 Paris Tél. — + 33 (0)1 43 26 89 80 e-mail — [email protected] www.galeriepaulproute.com PAUL PROUTÉ GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 1 30/10/2020 16:15:36 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 1920 2020 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 500 ESTAMPES 2020 SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................... 7 PRÉFACE ................................................................................ 9 ESTAMPES DES XVIe ET XVIIe SIÈCLES ............................. 15 ESTAMPES DU XVIIIe SIÈCLE ............................................. 61 ESTAMPES DU XIXe SIÈCLE ................................................ 105 ESTAMPES DU XXe SIÈCLE ................................................. 171 INDEX .................................................................................... 202 AVANT-PROPOS près avoir quitté la maison familiale du 12 de la rue de Seine, Paul Prouté s’instal- Alait au 74 de cette même rue le 15 janvier -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

The Art Digest 1929-12-01: Vol 4 Iss 5

8 on DEC 6 1929 ger » The ART DIGEST Combined with THE Arcus of San Francisco The News --Magazine of Art “LADY WITH A GOLD CHAIN,” BY LUCAS CRANACH (1472-1553). A “German Mona Lisa.” Shown at the Van Diemen Galleries’ Cranach Exhibition. Reproduced by Courtesy of the Owner, Edouard Jonas. nil FIRST-DECEMBER 1929 TWENTY-FIVE CENTS The Art Digest, rst December, 1929 JACQUES SELIGMANN & C° 3 East 51st Street, New York PAINTINGS and WORKS of cART Ancien Palais Sagan, Rue St. Dominique PARIS 9 Rue de la Paix JOHN LEVY cALLERY “The 0 GALLERIES P. Jackson Higgs” : ; 11 EAST 54th STREET Paintings NEW YORK 5 NEW YORK 559 FIFTH AVENUE HIGH CLASS OLD MASTERS ANTIQUITIES THOMAS J. KERR HOWARD YOUNG GALLERIES formerly with DuvEEN BROTHERS IMPORTANT PAINTINGS IMPORTANT PAINTINGS Old and Modern By O_p Masters ANTIQUE Works OF ArT IIIS IIIAIAAIIIIT peppers | NEW YORK LONDON TAPESTRIES FURNITURE er 35 OLD BoND STREET 510 Mapison AvENvE (4th floor) New York | Duranp-Ruet ||| FERARGIL ||] KHRICH NEW YORK F. NEwLin Price, President GALLE RI ES 12 East Fifty-Seventh Street eee cane i Paintings PARIS 37 East Fifty-Seventh St. poe aS. 37 Avenue de Friedland NEW YORK 36 East 5 7th Street New York GRACE HORNE’S BRODERICK GALLERIES GALLERIES BUFFALO, N. Y. Stuart at Dartmouth, BOSTON Paintings Prints Yorke Ballery Throughout the season a series of Antiques Continuous Exhibitions of Paintings selected exhibitions of the best in by American and European Artists OLD ENGLISH SILVER AND CONTEMPORARY ART SHEFFIELD PLATE 2000 S St. WASHINGTON, D.C. The Art Digest, rst December, 1929 3 —_—— — Est. -

Divisionismo La Rivoluzione Della Luce

DIVISIONISMO LA RIVOLUZIONE DELLA LUCE a cura di Annie-Paule Quinsac Novara, Castello Visconteo Sforzesco 23.11.2019 - 05.04.2020 Il Comune di Novara, la Fondazione Castello Visconteo e l’associazione METS Percorsi d’arte hanno in programma per l’autunno e l’inverno 2019-2020 nelle sale dell’imponente sede del Castello Visconteo Sfor- zesco – ristrutturate a regole d’arte per una vocazione museale – un’im- Gaetano Previati Maternità 1 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO portante mostra dedicata al Divisionismo, un movimento giustamente considerato prima avanguardia in Italia. Per la sua posizione geografica, a 45 km dal Monferrato, fonte iconografica imprescindibile nell’opera di Angelo Morbelli (1853-1919), e appena più di cento dalla Volpedo di Giuseppe Pellizza (1868-1907) – senza dimenticare la Valle Vigezzo di Carlo Fornara (1871-1968) che fino a pochi anni era amministrativa- mente sotto la sua giurisdizione – Novara, infatti, è luogo deputato per ospitare questa rassegna. Sono appunto i rapporti con il territorio che hanno determinato le scelte e il taglio della manifestazione. incentrata sul Divisionismo lombardo-piemontese. Giovanni Segantini All’ovile 2 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO La curatela è stata affidata ad Annie-Paule Quinsac, tra i primissimi storici dell’arte ad essersi dedicata al Divisionismo sul finire degli anni Sessanta del secolo scorso, esperta in particolare di Giovanni Segantini – figura che ha dominato l’arte europea dagli anni Novanta alla Prima guerra mondiale –, del vigezzino Carlo Fornara e di Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, artisti ai quali la studiosa ha dedicato fondamentali pubblicazio- ni ed esposizioni. Il Divisionismo nasce a Milano, sulla stessa premessa del Neo-Im- pressionnisme francese (meglio noto come Pointillisme), senza tuttavia Carlo Fornara Fontanalba 3 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO Angelo Morbelli Meditazione Emilio Longoni Bambino con trombetta e cavallino 4 DELLA LUCE LA RIVOLUZIONE DIVISIONISMO che si possa parlare di influenza diretta. -

To Theo Van Gogh and Jo Van Gogh-Bonger. Auvers-Sur-Oise, Sunday, 25 May 1890

To Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger. Auvers-sur-Oise, Sunday, 25 May 1890. Sunday, 25 May 1890 Metadata Source status: Original manuscript Location: Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. no. b686 V/1962 Date: On Monday, 2 June Theo wrote that he had wanted to reply earlier to the present letter, which must have been written shortly before a Tuesday (see l. 4). Van Gogh remarks that it has been raining yesterday and today (ll. 53-54). This must have been Saturday, 24 and Sunday, 25 May (Mto-France). On the basis of this information we have dated the letter to Sunday, 25 May 1890. On the same day Theo recorded in his account book the 50 francs for which Vincent thanks him in the first lines of the present letter (see Account book 2002, p. 45). See also Hulsker 1998, p. 51. Additional: This letter, which confirms the receipt this morning (ll. 1*-2) of the money Theo sent, most likely caused Vincent to decide not to send RM20 (this explains why the two letters contain several identical passages). Van Gogh enclosed a letter for Isacson (cf. RM21). Original [1r:1] Mon cher Theo, ma chre Jo, merci de ta lettre que jai reue ce matin1 et des cinquante francs qui sy trouvaient. Aujourdhui jai revu le Dr Gachet et je vais peindre chez lui Mardi matin puis je dinerais avec lui et aprs il viendrait voir ma peinture. Il me parait trs raisonable mais est aussi decourag dans son metier de mdecin de campagne que moi de ma peinture. -

Vincent Van Gogh Le Fou De Peinture

VINCENT VAN GOGH Le fou de peinture Texte Pascal BONAFOUX lu par l’auteur et Julien ALLOUF translated by Marguerite STORM read by Stephanie MATARD LETTRES DE VAN GOGH lues par MICHAEL LONSDALE © Éditions Thélème, Paris, 2020 CONTENTS SOMMAIRE 6 6 Anton Mauve Anton Mauve The misunderstanding of a still life Le malentendu d’une nature morte Models, and a hope Des modèles et un espoir Portraits and appearance Portraits et apparition 22 22 A home Un chez soi Bedrooms Chambres The need to copy Nécessité de la copie The destiny of the doctors’ portraits Les destins de portraits de médecins Dialogue of painters Dialogue de peintres 56 56 Churches Églises Japanese prints Estampes japonaises Arles and money Arles et l’argent Nights Nuits 74 74 Sunflowers Tournesols Trees Arbres Roots Racines 94 ARTWORK INDEX 94 index des œuvres Anton Mauve 9 /34 Anton Mauve PAGE DE DROITE Nature morte avec chou et sabots 1881 Souvenir de Mauve 1888 Still Life with Cabbage and Clogs Reminiscence of Mauve 34 x 55 cm – Huile sur papier 73 x 60 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Pays-Bas 6 7 Le malentendu d’une nature morte 10 /35 The misunderstanding of a still life Nature morte à la bible 1885 Still life with Bible 65,7 x 78,5 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas 8 9 Souliers 1888 Shoes 45,7 x 55,2 cm – Huile sur toile The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA 10 11 Vue de la fenêtre de l’atelier de Vincent en hiver 1883 View from the window of Vincent’s studio in winter 20,7 x -

1998 Education

1998 Education JANUARY JUNE 11 Video: Alfred Steiglitz: Photographer 2–5 Workshop: Drawing for the Doubtful, Earnest Ward, artist 17 Teacher Workshop: The Art of Making Books 3 Video: Masters of Illusion 18 Gallery Talk: Arthur Dove’s Nature Abstraction, 10 Video: Cezanne: The Riddle of the Bathers Rose M. Glennon, Curator of Education 17 Video: Mondrian 25 Members Preview: O’Keeffe and Texas 21 Gallery Talk: Nature and Symbol: Impressionist and 26 Colloquium: The Making of the O’Keeffe and Texas Post-impressionism Prints from the McNay Collection, Exhibition, Sharyn Udall, Art Historian, William J. Chiego, Lyle Williams, Curator, Prints and Drawings Director, Rose M. Glennon, Curator of Education 22 Lecture and Members Preveiw: The Garden Setting: Nature Designed, Linda Hardberger, Curator of the Tobin FEBRUARY Collection of Theatre Arts 1 Video: Women in Art: O’Keeffe 24 Teacher Workshop: Arts in Education, Getty 8 Video: Georgia O’Keeffe: The Plains on Paper Education Institute 12 Gallery Talk: Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe and American Nature, Charles C. Eldredge, title? JULY 15 Video: Alfred Stieglitz: Photographer 7 Members Preview: Kent Rush Retrospective 21 Symposium: O’Keeffe in Texas 12 Gallery Talk: A Discourse on the Non-discursive, Kent Rush, artist MARCH 18 Performance: A Different Notion of Beautiful, Gemini Ink 1 Video: Women in Art: O’Keeffe 19 Performance: A Different Notion of Beautiful, Gemini Ink 8 Lunch and Lecture: A Photographic Affair: Stieglitz’s 26 Gallery Talk: Kent Rush Retrospective, Lyle Williams, Portraits -

Relazione Sulla Gestione 2012

2012 BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO AL 31 DICEMBRE 2012 In copertina: Carlo Fornara, Il seminatore, 1895, olio su tela, cm. 26,5 x 34 - collezione d’arte della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2 FONDAZIONE CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI TORTONA BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO AL 31 DICEMBRE 2012 SOMMARIO 4 Relazione sulla gestione 157 Prospetti di bilancio 159 Nota integrativa 209 Relazione del Collegio dei Revisori ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3 FONDAZIONE CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI TORTONA BILANCIO D’ESERCIZIO AL 31 DICEMBRE 2012 RELAZIONE SULLA GESTIONE INTRODUZIONE – QUADRO NORMATIVO DI RIFERIMENTO Il 31 dicembre 2012 si è chiuso il ventunesimo esercizio della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona. Il quadro di riferimento normativo relativo allo scorso esercizio è stato caratterizzato da numerosi interventi legislativi che hanno inciso, in alcuni casi significativamente, sull’attività delle fondazioni bancarie. Di seguito una breve panoramica su tali novità. Governance delle Fondazioni L’art. 27-quater della legge n. 27/2012 ha apportato alcune integrazioni all’art. 4, comma 1, del D. Lgs. n. 153/99. In particolare, in tema di requisiti dei componenti l’Organo di Indirizzo delle Fondazioni, viene previsto il ricorso a modalità di designazione ispirate a criteri oggettivi e trasparenti, improntati alla valorizzazione dei principi di onorabilità e professionalità. Viene poi inserita una ulteriore ipotesi di incompatibilità riferita ai soggetti che svolgono funzioni di indirizzo, amministrazione, direzione e controllo presso le Fondazioni: trattasi dell’impossibilità, per tali soggetti, di assumere od esercitare cariche negli organi gestionali, di sorveglianza e di controllo o funzioni di direzione di società concorrenti della società bancaria conferitaria o di società del gruppo. -

Claude Monet : Seasons and Moments by William C

Claude Monet : seasons and moments By William C. Seitz Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1960 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Museum: Distributed by Doubleday & Co. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2842 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The Museum of Modern Art, New York Seasons and Moments 64 pages, 50 illustrations (9 in color) $ 3.50 ''Mliili ^ 1* " CLAUDE MONET: Seasons and Moments LIBRARY by William C. Seitz Museumof MotfwnArt ARCHIVE Claude Monet was the purest and most characteristic master of Impressionism. The fundamental principle of his art was a new, wholly perceptual observation of the most fleeting aspects of nature — of moving clouds and water, sun and shadow, rain and snow, mist and fog, dawn and sunset. Over a period of almost seventy years, from the late 1850s to his death in 1926, Monet must have pro duced close to 3,000 paintings, the vast majority of which were landscapes, seascapes, and river scenes. As his involvement with nature became more com plete, he turned from general representations of season and light to paint more specific, momentary, and transitory effects of weather and atmosphere. Late in the seventies he began to repeat his subjects at different seasons of the year or moments of the day, and in the nineties this became a regular procedure that resulted in his well-known "series " — Haystacks, Poplars, Cathedrals, Views of the Thames, Water ERRATA Lilies, etc. -

出品作品リスト| List of Works

主 催:東京都美術館(公益財団法人東京都歴史文化財団)、東京新聞、TBS 後 援:オ ラ ン ダ 王 国 大 使 館 、 TBSラ ジ オ、 BS - TBS 協 賛:三井住友銀行、日本写真印刷、三井物産、損保ジャパン日本興亜 協 力:エールフランス航 空 / K L M オランダ航 空、日本航 空、オランダ 政 府観 光 局 Organized by:Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)/The Tokyo Shimbun/TBS With the support of:Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands/ TBS RADIO, Inc./BS - TBS With the sponsorship of:Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation/Nissha Printing Co., Ltd./MITSUI & CO., LTD. /Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Insurance Inc. With the cooperation of:Air France / KLM Royal Dutch Airlines/JAPAN AIRLINES/ Netherlands Board of Tourism & Conventions 本展は、政府による美術品補償制度の適用を受けています。 This exhibition is covered by the Japanese Act on the Indemnification of Damage to Works of Art in Exhibitions (Act No.17 of 2011) 出品 作 品リスト | List of Works ・本リストの掲載順と作品展示順は必ずしも一致しません。 ・ 展示室内の温度・湿度、照明は、作品保護に関する所蔵者の貸出条件に従い管理しております。ご来場の皆様にとって理想的と感じられない場合もあるかと存じますが、 ご容赦ください。 ・作品番号 10、11、27、29、53、62 は東京会場に出品されないため、本リストには掲載しておりません。 ・The order of the work in this list may not necessarily correspond to that in the exhibition. ・Temperature, humidity and brightness of the exhibition room are controlled under the lender's condition of loan and international standard for preservation of work. We apologize any inconvenience this may cause. ・Work nos. 10, 11, 27, 29, 53, 62 will not be displayed in Tokyo. 番号 作家名 作品名 制作年 技法・材質 所蔵 No. Artist Title Year Technique / Material Collection 第1章 近代絵画のパイオニア誕生 The Making of the Two Fathers of Modern Art 1 フィン セ ント ・ファン ・ゴッホ 泥炭船と二人の人物 1883 油彩、 ドレント美 術 館 板 に -

Working in Fields of Sunshine by HEIDI J

42 Work Due to copyright restrictions, this image is only available in the print version of Christian Reflection. Van Gogh celebrates the peasant workers who toil in this vineyard in southern France. They enjoy the open air and sunshine the artist loved. Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), THE RED VINEYARD (1888). Oil on canvas. 29.5” x 36.3”. Puskin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia. Photo: Scala / Art Resource. Used by permission. Copyright © 2015 Institute for Faith and Learning at Baylor University 43 Working in Fields of Sunshine BY HEIDI J. HORNIK he workers depicted here by Vincent van Gogh are the subject of the only painting by the artist known to have been purchased during This lifetime. It is believed that he painted the vineyard from memory. Van Gogh had worked and studied in London, Antwerp, and The Hague. But it is not until seeing the paintings of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists in Paris that he changed his palette dramatically in 1887 to use brighter, less opaque colors. Like the Impressionists, he painted from life, preferred the use of natural light, and employed the synthetic evocation of color through Divisionism (the juxtaposition of small touches of pure, unmixed pigment directly on the canvas). This last characteristic became the expressive trademark of his later works.1 In February 1888, Van Gogh left the bustle of Paris to live in Arles, a small town in southern France. He was inspired by Jean-Francois Millet’s paintings that focused on the work of the common peasant. Van Gogh enjoyed studying the workers as he viewed the golden wheat fields, the blossoming orchards, and sunflowers that appear in his later and most famous paintings. -

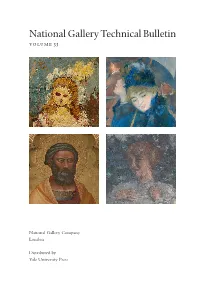

Adolphe Monticelli, Subject Composition (NG 5010), Reverse, Probably 1870–86 (Detail)

National Gallery Technical Bulletin volume 33 National Gallery Company London Distributed by Yale University Press 001-003 TB33 16.8.indd 1 17/08/2012 07:37 This edition of the Technical Bulletin has been funded by the American Friends of the National Gallery, London with a generous donation from Mrs Charles Wrightsman Series editor: Ashok Roy Photographic credits © National Gallery Company Limited 2012 All photographs reproduced in this Bulletin are © The National Gallery, London unless credited otherwise below. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including CHICAGO photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence: prior permission in writing from the publisher. fi g. 9, p. 77. Articles published online on the National Gallery website FLORENCE may be downloaded for private study only. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence © Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library: fi g. 45, p. 45; © 2012. Photo Scala, First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali: fig. 43, p. 44. National Gallery Company Limited St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street LONDON London WC2H 7HH The British Library, London © The British Library Board: fi g. 15, p. 91. www.nationalgallery. co.uk MUNICH British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich A catalogue record is available from the British Library. © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence/BPK, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin: fig. 47, p. 46 (centre pinnacle); fi g.