The Bodo Movement and Situating Identity Assertions in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bodo Movement: Past and Present

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) THE BODO MOVEMENT: PAST AND PRESENT Berlao K. Karjie Research Scholar Dept. of Political Science Bodoland University INTRODUCTION The Boro or Bodo or Kachari is the earliest known inhabitant of Assam. The Bodos belong to racial origin of Mongoloid group. The Mongoloid population over time had formed a solid bloc spreading throughout the Brahmaputra and Barak valleys stretching to Cachar Hills of Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura extending to some parts of West Bengal, Bihar, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh with different identities. The Boro, Borok (Tripuri), Garo, Dimasa, Rabha, Chutiya, Tiwa, Sarania, Moholia, Kachari, Deuri, Borahi, Modahi, Sonowal, Thengal, Dhimal, Koch, Mech, Meche, Barman, Moran, Hajong, Rhamsa are historically, racially and linguistically of same ancestry. Since the historically untraced ages, the Bodo had exercised their highly developed political, legal and socio-cultural influences. Today the majority of Bodos are found concentrated in the foot hills of the Himalayan ranges in the north bank of the Brahmaputra valley. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE BODO NATION The Bodos had a glorious past history which is found mentioned in Hindu mythology like Vedic literature and epic like Mahabharata, Ramayana and Puranas with different derogatory names like Ausura, Mlecha and Kirata dynasty. The Bodos had once ruled the entire part of Himalayan ranges extending to Brahmaputra valley with different names and dynasties. For the first time in the recorded history the Ahoms attacked and invaded their country in the early part of the 13th century which continued almost 200 years. Despite of many external invasions the Bodos lived as a free nation with dignity and honour till the British invaded their dominions. -

6.Hum-RECEPTION and TRANSLATION of INDIAN

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(E): 2321-8878; ISSN(P): 2347-4564 Vol. 3, Issue 12, Dec 2015, 53-58 © Impact Journals RECEPTION AND TRANSLATION OF INDIAN LITERATURE INTO BORO AND ITS IMPACT IN THE BORO SOCIETY PHUKAN CH. BASUMATARY Associate Professor, Department of Bodo, Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Assam, India ABSTRACT Reception is an enthusiastic state of mind which results a positive context for diffusing cultural elements and features; even it happens knowingly or unknowingly due to mutual contact in multicultural context. It is worth to mention that the process of translation of literary works or literary genres done from one language to other has a wide range of impact in transmission of culture and its value. On the one hand it helps to bridge mutual intelligibility among the linguistic communities; and furthermore in building social harmony. Keeping in view towards the sociological importance and academic value translation is now-a-day becoming major discipline in the study of comparative literature as well as cultural and literary relations. From this perspective translation is not only a means of transference of text or knowledge from one language to other; but an effective tool for creating a situation of discourse among the cultural surroundings. In this brief discussion basically three major issues have been taken into account. These are (i) situation and reason of welcoming Indian literature and (ii) the process of translation of Indian literature into Boro and (iii) its impact in the society in adaption of translation works. KEYWORDS: Reception, Translation, Transmission of Culture, Discourse, Social Harmony, Impact INTRODUCTION The Boro language is now-a-day a scheduled language recognized by the Government of India in 2003. -

Corpus Building of Literary Lesser Rich Language-Bodo: Insights And

Corpus Building of Literary Lesser Rich Language- Bodo: Insights and Challenges Biswajit Brahma1 Anup Kr. Barman1 Prof. Shikhar Kr. Sarma1 Bhatima Boro1 (1) DEPT. OF IT, GAUHATI UNIVERSITY, Guwahati - 781014, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Collection of natural language texts in to a machine readable format for investigating various linguistic phenomenons is call a corpus. A well structured corpus can help to know how people used that language in day-to-day life and to build an intelligent system that can understand natural language texts. Here we review our experience with building a corpus containing 1.5 million words of Bodo language. Bodo is a Sino Tibetan family language mainly spoken in Northern parts of Assam, the North Eastern state of India. We try to improve the quality of Bodo corpora considering various characteristics like representativeness, machine readability, finite size etc. Since Bodo is one of the Indian language which is lesser reach on literary and computationally we face big problem on collecting data and our generated corpus will help the researchers in both field. KEYWORD : Bodo language, Corpus, Linguistics, Natural Language Processing. Proceedings of the 10th Workshop on Asian Language Resources, pages 29–34, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 29 1 Introduction The term corpus is derived from Latin corpus "body” which it means as a representative collection of texts of a given language, dialect or other subset of a language to be used for linguistic analysis. Precisely, it refers to (a) (loosely) anybody of text; (b) (most commonly) a body of machine readable text; and (c) (more strictly) a finite collection of machine-readable texts sampled to be representative of a language or variety (Mc Enery and Wilson 1996: 218). -

Identity Politics and Social Exclusion in India's North-East

Identity Politics and Social Exclusion in India’s North-East: The Case for Re-distributive Justice N.K.Das• Abstract: This paper examines how various brands of identity politics since the colonial days have served to create the basis of exclusion of groups, resulting in various forms of rifts, often envisaged in binary terms: majority-minority; sons of the soil’-immigrants; local-outsiders; tribal-non-tribal; hills-plains; inter-tribal; and intra-tribal. Given the strategic and sensitive border areas, low level of development, immense cultural diversity, and participatory democratic processes, social exclusion has resulted in perceptions of marginalization, deprivation, and identity losses, all adding to the strong basis of brands of separatist movements in the garb of regionalism, sub-nationalism, and ethnic politics, most often verging on extremism and secession. It is argued that local people’s anxiety for preservation of culture and language, often appearing as ‘narcissist self-awareness’, and their demand of autonomy, cannot be seen unilaterally as dysfunctional for a healthy civil society. Their aspirations should be seen rather as prerequisites for distributive justice, which no nation state can neglect. Colonial Impact and genesis of early ethnic consciousness: Northeast India is a politically vital and strategically vulnerable region of India. Surrounded by five countries, it is connected with the rest of India through a narrow, thirty-kilometre corridor. North-East India, then called Assam, is divided into Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. Diversities in terms of Mongoloid ethnic origins, linguistic variation and religious pluralism characterise the region. This ethnic-linguistic-ecological historical heritage characterizes the pervasiveness of the ethnic populations and Tibeto-Burman languages in northeast. -

Swarna Prabha Chainary Community As a Whole

ISSN No. : 2394-0344 REMARKING : VOL-1 * ISSUE-9*February-2015 Survival of Boro Language in the Face of Various Challenges (with Reference to Modern Period) Abstract This paper tries to give an idea on how the Boro peoples are struggling in different periods to keep them and their language alive. Starting from the medium of instruction in their language to the movement demanding Roman script to write their language as well as Bodo accord for formation of Bodoland Autonomous Council in 1993 and later on Bodoland Territorial Area District in 2003 they are not getting it without fighting and without sacrificing the valuable lives of the innocent peoples. Keywords: ABSU, bodo accord, BPAC, Dhubri Boro Literary Club, PTCA. Introduction Boro language is a language belonging to Assam and is recognized as a schedule language under Indian Constitution from the year 2003. The history of survival of this language and its speakers is a big challenge whether it is language, literature, culture, politics or economics. Therefore, when going to discuss on the topic Survival of Boro Language in the Face of Various Challenges, one cannot discuss only the language in isolation, the two other fields literature and politics will come up side by side. Considering this, discussion will cover the period from the formation of the Bodo Sahitya Sabha, the apex socio-literary organization of the Boros on16th November 1952 as it is considered by the Boro intellectuals and the litterateurs not only as the milestone of the beginning of modern Boro literature but also as the year of the revival of language and the Swarna Prabha Chainary community as a whole. -

List of Acs Revenue & Election District Wise

List of Assembly Constituencies showing their Revenue & Election District wise break - up Name of the District Name of the Election Assembly Constituency Districts No. Name 1. Karimganj 1-Karimganj 1 Ratabari (SC) 2 Patharkandi 3 Karimganj North 4 Karimganj South 5 Badarpur 2. Hailakandi 2-Hailakandi 6 Hailakandi 7 Katlicherra 8 Algapur 3. Cachar 3-Silchar 9 Silchar 10 Sonai 11 Dholai (SC) 12 Udharbond 13 Lakhipur 14 Barkhola 15 Katigorah 4. Dima Hasao 4-Haflong 16 Halflong (ST) 5. Karbi Anglong 5-Bokajan 17 Bokajan (ST) 6-Diphu 18 Howraghat (ST) 19 Diphu (ST) 6. West Karbi Anglong 7-Hamren 20 Baithalangso (ST) 7. South Salmara 8-South Salmara 21 Mankachar Mankachar 22 Salmara South 8. Dhubri 9-Dhubri 23 Dhubri 24 Gauripur 25 Golakganj 26 Bilasipara West 10-Bilasipara 27 Bilasipara East 9. Kokrajhar 11-Gossaigaon 28 Gossaigaon 29 Kokrajhar West (ST) 12-Kokrajhar 30 Kokrajhar East (ST) 10. Chirang 13-Chirang 31 Sidli (ST) 14-Bijni 33 Bijni 11. Bongaigaon 15-Bogaigaon 32 Bongaigaon 16-North Salmara 34 Abhayapuri North 35 Abhayapuri South (SC) 12. Goalpara 17-Goalpara 36 Dudhnoi (ST) 37 Goalpara East 38 Goalpara West 39 Jaleswar 13. Barpeta 18-Barpeta 40 Sorbhog 43 Barpeta 44 Jania 45 Baghbor 46 Sarukhetri 47 Chenga 19-Bajali 41 Bhabanipur 42 Patacharkuchi Page 1 of 3 Name of the District Name of the Election Assembly Constituency Districts No. Name 14. Kamrup 20-Guwahati 48 Boko (SC) 49 Chaygaon 50 Palasbari 55 Hajo 21-Rangia 56 Kamalpur 57 Rangia 15. Kamrup Metro 22-Guwahati (Sadar) 51 Jalukbari 52 Dispur 53 Gauhati East 54 Gauhati West 16. -

Language, Part IV B(I)(A)-C-Series, Series-4, Assam

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 04 - ASSAM PART IV B(i)(a) - C-Series LANGUAGE Table C-7 State, Districts, Circles and Towns DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, ASSAM Registrar General of India (tn charge of the Census of India and vital statistics) Office Address: 2-A. Mansingh Road. New Delhi 110011. India Telephone: (91-11) 338 3761 Fax: (91-11) 338 3145 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.censusindia.net Registrar General of India's publications can be purchased from the following: • The Sales Depot (Phone: 338 6583) Office of the Registrar General of India 2-A Mansingh Road New Delhi 110 011, India • Directorates of Census Operations in the capitals of all states and union territories in India • The Controller of Publication Old Secretariat Civil Lines Delhi 110054 • Kitab Mahal State Emporium Complex, Unit No.21 Saba Kharak Singh Marg New Delhi 110 001 • Sales outlets of the Controller of Publication aU over India • Census data available on the floppy disks can be purchased from the following: • Office of the Registrar i3enerai, india Data Processing Division 2nd Floor. 'E' Wing Pushpa Shawan Madangir Road New Delhi 110 062, India Telephone: (91-11) 608 1558 Fax: (91-11) 608 0295 Email: [email protected] o Registrar General of India The contents of this publication may be quoted citing the source clearly PREFACE This volume contains data on language which was collected through the Individual Slip canvassed during 1991 Censlis. Mother tongue is a major social characteristic of a person. The figures of mother tongue were compiled and grouped under the relevant language for presentation in the final table. -

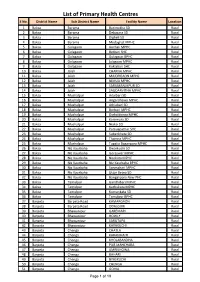

List of Primary Health Centres S No

List of Primary Health Centres S No. District Name Sub District Name Facility Name Location 1 Baksa Barama Barimakha SD Rural 2 Baksa Barama Debasara SD Rural 3 Baksa Barama Digheli SD Rural 4 Baksa Barama Medaghat MPHC Rural 5 Baksa Golagaon Anchali MPHC Rural 6 Baksa Golagaon Betbari SHC Rural 7 Baksa Golagaon Golagaon BPHC Rural 8 Baksa Golagaon Jalagaon MPHC Rural 9 Baksa Golagaon Koklabari SHC Rural 10 Baksa Jalah CHARNA MPHC Rural 11 Baksa Jalah MAJORGAON MPHC Rural 12 Baksa Jalah NIMUA MPHC Rural 13 Baksa Jalah SARUMANLKPUR SD Rural 14 Baksa Jalah SAUDARVITHA MPHC Rural 15 Baksa Mushalpur Adalbari SD Rural 16 Baksa Mushalpur Angardhawa MPHC Rural 17 Baksa Mushalpur Athiabari SD Rural 18 Baksa Mushalpur Borbori MPHC Rural 19 Baksa Mushalpur Dighaldonga MPHC Rural 20 Baksa Mushalpur Karemura SD Rural 21 Baksa Mushalpur Niaksi SD Rural 22 Baksa Mushalpur Pamuapathar SHC Rural 23 Baksa Mushalpur Subankhata SD Rural 24 Baksa Mushalpur Thamna MPHC Rural 25 Baksa Mushalpur Tupalia Baganpara MPHC Rural 26 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Dwarkuchi SD Rural 27 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Goreswar MPHC Rural 28 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Naokata MPHC Rural 29 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Niz Kaurbaha BPHC Rural 30 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Sonmahari MPHC Rural 31 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Uttar Betna SD Rural 32 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Bangalipara New PHC Rural 33 Baksa Tamulpur Gandhibari MPHC Rural 34 Baksa Tamulpur Kachukata MPHC Rural 35 Baksa Tamulpur Kumarikata SD Rural 36 Baksa Tamulpur Tamulpur BPHC Rural 37 Barpeta Barpeta Road KAMARGAON Rural 38 Barpeta Barpeta Road ODALGURI Rural 39 Barpeta -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 13888-IN STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized ASSAM RURAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND AGRICULTURAL SERVICES PROJECT APRIL 26, 1995 Public Disclosure Authorized Agriculture and Water Operations Division Country Department II Public Disclosure Authorized South Asia Region CURRENCY EOUIVALENTS US$ 1 = Rupees (Rs) 31.4 (December 1994) FISCAL YEAR GOI, State - April 1 to March 31 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES The metric system is used throughout the report LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS Assam Agro-Industries Development Corporation Assam Council for Technology, Science and Environment Agricultural Development Project Agricultural Extension Officer Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Department Artificial Insemination Agricultural Production Commissioner Assam State Agricultural University Assam Seed Corporation Assam State Electricity Board Agricultural Strategy Paper Assam State Seed Certification Agency Country Assistance Strategy Central Ground Water Board Department of Agriculture District Rural Development Agency Deep Tube Wells Economic Rate of Return Fish Farmers Development Agency Field Management Committee Farming Systems Research Field Trial Station Gross Domestic Product Government of Assam Government of India Government of Tamil Nadu Gaon Panchayat Samabay Samathi High Yielding Varieties Indian Council for Agricultural Research International Competitive Bidding Intensive Cattle Development Project Irrigation Department Integrated Rural Development Project Million -

Identity and Violence in India's North East: Towards a New Paradigm

Identity and Violence In India’s North East Towards a New Paradigm Sanjib Goswami Institute for Social Research Swinburne University of Technology Australia Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Ethics Clearance for this SUHREC Project 2013/111 is enclosed Abstract This thesis focuses on contemporary ethnic and social conflict in India’s North East. It concentrates on the consequences of indirect rule colonialism and emphasises the ways in which colonial constructions of ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ identity still inform social and ethnic strife. This thesis’ first part focuses on history and historiography and outlines the ways in which indirect rule colonialism was implemented in colonial Assam after a shift away from an emphasis on Britain’s ‘civilizing mission’ targeting indigenous elites. A homogenising project was then replaced by one focusing on the management of colonial populations that were perceived as inherently distinct from each other. Indirect rule drew the boundaries separating different colonised constituencies. These boundaries proved resilient and this thesis outlines the ways in which indirect rule was later incorporated into the constitution and political practice of postcolonial India. Eventually, the governmental paradigm associated with indirect rule gave rise to a differentiated citizenship, a dual administration, and a triangular system of social relations comprising ‘indigenous’ groups, non-indigenous Assamese, and ‘migrants’. Using settler colonial studies as an interpretative paradigm, and a number of semi-structured interviews with community spokespersons, this thesis’ second part focuses on the ways in which different constituencies in India’s North East perceive ethnic identity, ongoing violence, ‘homeland’, and construct different narratives pertaining to social and ethnic conflict. -

Brajendra Kumar Brahma's Biographical Essays

© 2018 JETIR November 2018, Volume 5, Issue 11 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) BRAJENDRA KUMAR BRAHMA’S BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS Dhanan Brahma Research Scholar Department of Bodo Gauhati University, Guwahati, India Abstract : Brajendra Kumar Brahma is an eminent Bodo non-fiction writer. Besides non-fiction he writes poetry also. He has publications of many non-fiction writings like essays, literary criticisms, biographical writings, memoirs etc. Biographical writings are also mentionable among his creations. Biographies of noted persons have valuable lessons. The readers can learn many things from them. He has written biographical essays on some noted persons from the Bodo community those who have lots of contributions towards the upliftment of Bodo society. He has portrayed about their life and works of the personalities according to their field of contributions nicely. This paper is the study of biographical essays of Brajendra Kumar Brahma. Keywords- Bodo non-fiction, biographical essays, noted persons. INTRODUCTION Brajendra Kumar Brahma is an eminent writer of Bodo literature. He has written many poems and prose in Bodo literature. He often writes short stories. Modern poetry in Bodo literature began in the second half of twentieth century. Brajendra Kumar Brahma is the pioneer of the trends of modern Bodo poetry. With the publication of Okhrang Gonggse Nanggou ‘Need of a Sky’ (1975) he established modern trends of Bodo poetry. He is also an eminent writer of Bodo non-fictional literature. His writings like essays, literary criticisms, -

History Research Journal ISSN: 0976-5425 Vol-5-Issue-5-September-October-2019

History Research Journal ISSN: 0976-5425 Vol-5-Issue-5-September-October-2019 The History Of Education And The Literary Development Of The Bodo In The Brahmaputra Valley Dr. Oinam Ranjit Singh Associate Professor Department of History Bodoland University Kokrajhar BTC, Assam Email: [email protected] Umananda Basumatary Research scholar, Department of History Bodoland University Abstract The education is regarded as the invincible element for the development of a society. Without the progress of education the rate of development index of a particular society cannot be measured. The Bodos are the single largest aboriginal tribe living in the Brahmaputra valley of Assam from the time immemorial. They possessed rich socio-cultural tradition and solid language of their own. In the early 19th century on the eve of British intervention in Assam the condition of education among the Bodos was completely in a stake. It was after the adoption of the education policy in Assam by British Government the ray of educational hope reached to the Bodos. It was undeniable fact that the Christian Missionaries also played an important role in disseminating western education among the Bodos through their evangelical objectives in view. They established many schools in the remote places of the Bodo populated areas to spread the education. Besides that the Christian Missionaries left many literary activities among the Bodos as a credit in their account. These missionary activities awaken the educated elite sections of the Bodos to promulgate social reform movement by the means of literary activities. As a consequence in the early part of the 20th century under the banner of Boro Chatra Sanmilani some of the educated Bodo youths had started to publish series of magazines like Bibar, Jenthoka and Alongbar etc.