Protest Networks, Communicative Mechanisms and State Responses: Ethnic Mobilization and Violence in Northeast India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bodo Movement: Past and Present

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) THE BODO MOVEMENT: PAST AND PRESENT Berlao K. Karjie Research Scholar Dept. of Political Science Bodoland University INTRODUCTION The Boro or Bodo or Kachari is the earliest known inhabitant of Assam. The Bodos belong to racial origin of Mongoloid group. The Mongoloid population over time had formed a solid bloc spreading throughout the Brahmaputra and Barak valleys stretching to Cachar Hills of Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura extending to some parts of West Bengal, Bihar, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh with different identities. The Boro, Borok (Tripuri), Garo, Dimasa, Rabha, Chutiya, Tiwa, Sarania, Moholia, Kachari, Deuri, Borahi, Modahi, Sonowal, Thengal, Dhimal, Koch, Mech, Meche, Barman, Moran, Hajong, Rhamsa are historically, racially and linguistically of same ancestry. Since the historically untraced ages, the Bodo had exercised their highly developed political, legal and socio-cultural influences. Today the majority of Bodos are found concentrated in the foot hills of the Himalayan ranges in the north bank of the Brahmaputra valley. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE BODO NATION The Bodos had a glorious past history which is found mentioned in Hindu mythology like Vedic literature and epic like Mahabharata, Ramayana and Puranas with different derogatory names like Ausura, Mlecha and Kirata dynasty. The Bodos had once ruled the entire part of Himalayan ranges extending to Brahmaputra valley with different names and dynasties. For the first time in the recorded history the Ahoms attacked and invaded their country in the early part of the 13th century which continued almost 200 years. Despite of many external invasions the Bodos lived as a free nation with dignity and honour till the British invaded their dominions. -

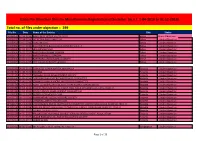

Total No. of Files Under Objection = 399 Status for Objection Files for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies (W.E.F. 1-04-2

Status for Objection files for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies (w.e.f. 1-04-2016 to 31-12-2016) Total no. of files under objection = 399 File No. Date Name of the Society Dist Status 01410052 07-04-2016 BAKULGURI NETAJI YOUTH CLUB Baksa Under Objection 01410053 07-04-2016 NIZ BETNA RAISHUMI CLUB Baksa Under Objection 01410059 03-11-2016 SURAJ (N.G.O) Baksa Under Objection 01410061 30-11-2016 BAGARIBARI B-BLOCK DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Baksa Under Objection 01410063 09-02-2017 SEUJ BIPLAB (NGO) Baksa Under Objection 01410064 24-02-2017 BAROPARA KRISHAK SANGHA Baksa Under Objection 01410065 24-02-2017 BAROPARA BIJULI SANGHA Baksa Under Objection 01410066 24-02-2017 BAROPARA ANJALI MAHILA SAMITY Baksa Under Objection 01410067 04-03-2017 TETELIGURI RUPJYOTI SANGHA Baksa Under Objection 02410193 24-08-2016 ZANNATUL AZHAR HAFIZIA MADRASSA Barpeta Under Objection 02410194 26-08-2016 ANURAG Barpeta Under Objection 02410196 01-09-2016 TARABARI CHAR DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Barpeta Under Objection 02410166 01-06-2016 GAREMARI NALA MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Barpeta Under Objection 02410167 01-06-2016 SONAKUCHI NALA MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Barpeta Under Objection 02410176 02-06-2016 BARPETA BRAHMAPUTRA VALLEY UPGRADING FORUM (NGO) Barpeta Under Objection 02410198 14-10-2016 RUPOSI ANCHALIK RURAL YOUTH WELFARE & CHILDREN CULTURAL SOCIETY Barpeta Under Objection 02410199 14-10-2016 MAZDIA RURAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Barpeta Under Objection 02410209 08-12-2016 PATBOUSI DAMODAR CLUB Barpeta Under Objection 02410210 14-12-2016 KAPAHARTARY SOCIAL WELFARE -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Sebuah Kajian Pustaka

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Conflicts in Northeast India: Intra-state conflicts with reference to Assam Dharitry Borah Debotosh Chakraborty Abstract Conflict in Northeast India has a brand entity that entrenched country‟s name in the world affairs for decades. In this paper, an attempt was made to study the genesis of conflicts in Northeast India with special emphasis on the intra-state conflicts in Assam. Attempts Keywords: were also made to highlight reasons why Northeast India has Conflict; remained to be a highly conflict ridden area comparing to other parts Sovereignty; of India. The findings revealed that the state has continued to be a Separate homeland; hub for several intra-state conflicts – as some particular groups raised Indian State demand for a sovereign state, while some others are betrothed in demanding for a separate state or homeland. There exists a strong nexus between historical circumstances and their intertwined influence on the contemporary conflict situations in the State. For these deep-rooted influences, critical suggestions are incorporated in order to deal with the conflicts and to bring sustainable and long- lasting peace in the State. Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India 715 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496Impact Factor: 7.081 1. -

Tradition of Mising Weaving Craft: an Analytical Study

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Tradition of Mising Weaving Craft: An analytical Study Dr. Bijoy Krishna Doley Assistant Professor, Department of Assamese Mahapurusha Srimanta Sankaradeva Viswavidyalaya Nagaon (Assam) Abstract: The Mising community people are living in different districts of Assam like Dhemaji, Lakhimpur, Dibrugarh, Tinisukia, Sonitpur, Darang, Golaghat, Jorhat, Sivasagar and Majuli. Mising are very rich in their Folk tradition and culture. They have contributed a lot to the greater Assamese cultural tradition. They have their own Folk-cultural tradition and craftsmanship as found in different Folk-crafts. Some of their traditional Folk-crafts have achieved fame and name across all over the Indian subcontinent. Here we can cite the example of their Weaving Craft. Along this Weaving Craft, their different Folk-crafts have its own traditional skill, art and craftsmanship. This have not only enriched their society and culture but has contributed a lot to the Socio-cultural scenario of greater Assamese society. In this study effort will be made to bring in to light the nature of the Weaving Craft of the Mising community living in two district of Assam, like Lakhimpur and Dhemaji district. So these include the study of traditional Weaving Crafts of this region. Keywords: Weaving, Folk-Craft, Loom. 0.0 Introduction: Mising Community is the second largest Community in Assam. The Misings officially recorded as Miri in the list of Scheduled Tribes of India under Constitution Order 1950 are originally a hill tribe of the Himalayan region of North Eastern India. Either for their better Wisdom or in their necessity of cultivable land. -

6.Hum-RECEPTION and TRANSLATION of INDIAN

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN(E): 2321-8878; ISSN(P): 2347-4564 Vol. 3, Issue 12, Dec 2015, 53-58 © Impact Journals RECEPTION AND TRANSLATION OF INDIAN LITERATURE INTO BORO AND ITS IMPACT IN THE BORO SOCIETY PHUKAN CH. BASUMATARY Associate Professor, Department of Bodo, Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Assam, India ABSTRACT Reception is an enthusiastic state of mind which results a positive context for diffusing cultural elements and features; even it happens knowingly or unknowingly due to mutual contact in multicultural context. It is worth to mention that the process of translation of literary works or literary genres done from one language to other has a wide range of impact in transmission of culture and its value. On the one hand it helps to bridge mutual intelligibility among the linguistic communities; and furthermore in building social harmony. Keeping in view towards the sociological importance and academic value translation is now-a-day becoming major discipline in the study of comparative literature as well as cultural and literary relations. From this perspective translation is not only a means of transference of text or knowledge from one language to other; but an effective tool for creating a situation of discourse among the cultural surroundings. In this brief discussion basically three major issues have been taken into account. These are (i) situation and reason of welcoming Indian literature and (ii) the process of translation of Indian literature into Boro and (iii) its impact in the society in adaption of translation works. KEYWORDS: Reception, Translation, Transmission of Culture, Discourse, Social Harmony, Impact INTRODUCTION The Boro language is now-a-day a scheduled language recognized by the Government of India in 2003. -

Quest for Nagalim: Mapping of Perceptions Outside Nagaland

Quest for Nagalim: Mapping of Perceptions Outside Nagaland Pradeep Singh Chhonkar Introduction The Nagas of Nagaland could always identify themselves with the Naga identity due to being in a state named after their own collective identity. However, the Naga tribes outside Nagaland, especially those of Manipur and Assam, always had a strong reason to reassert their Naga-ness. The response to the idea of a separate Nagalim has been wide-ranging across the entire region affected by Naga insurgency. A Framework Agreement was signed between the Government of India and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN-IM) on August 03, 2015. The agreement affected four states and approximately 35 Naga and other ethnic tribes inhabiting the traditional Naga areas. The agreement set three crucial parameters for the detailed settlement. First, it recognised that the Naga ‘history and situation’ was unique. Second, it proposed that sovereign powers would be shared between the Centre and the Nagas through a division of competencies, that is, through renegotiating the Union, State and Concurrent Lists of competencies of the Indian Constitution. Third, the two sides would strive for a mutually acceptable and peaceful settlement. While details of the accord are still shrouded in secrecy, it has been indicated that there will be no modification to the state boundaries. There Brigadier Pradeep Singh Chhonkar SM, VSM, is former Research Fellow at IDSA and presently commanding a Brigade in Northeast India. 80 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2018 QUEST FOR NAGALIM are indications about facilitation of cultural integration of the Nagas through special measures, and provision of financial and administrative autonomy of the Naga dominated areas in other states. -

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India's Northeast

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India’s Northeast? Ajai Sahni? India’s Northeast is the location of the earliest and longest lasting insurgency in the country, in Nagaland, where separatist violence commenced in 1952, as well as of a multiplicity of more recent conflicts that have proliferated, especially since the late 1970s. Every State in the region is currently affected by insurgent and terrorist violence,1 and four of these – Assam, Manipur, Nagaland and Tripura – witness scales of conflict that can be categorised as low intensity wars, defined as conflicts in which fatalities are over 100 but less than 1000 per annum. While there ? This Survey is based on research carried out under the Institute’s project on “Planning for Development and Security in India’s Northeast”, supported by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). It draws on a variety of sources, including Institute for Conflict Management – South Asia Terrorism Portal data and analysis, and specific State Reports from Wasbir Hussain (Assam); Pradeep Phanjoubam (Manipur) and Sekhar Datta (Tripura). ? Dr. Ajai Sahni is Executive Director, Institute for Conflict Management (ICM) and Executive Editor, Faultlines: Writings on Conflict and Resolution. 1 Within the context of conflicts in the Northeast, it is not useful to narrowly define ‘insurgency’ or ‘terrorism’, as anti-state groups in the region mix in a wide range of patterns of violence that target both the state’s agencies as well as civilians. Such violence, moreover, meshes indistinguishably with a wide range of purely criminal actions, including drug-running and abduction on an organised scale. Both the terms – terrorism and insurgency – are, consequently, used in this paper, as neither is sufficient or accurate on its own. -

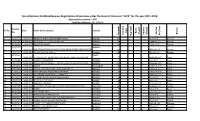

Fee Collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies Under The

Fee collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies under the Head of Accounts "1475" for the year 2017-2018 Applications recieved = 1837 Total fee collected = Rs. 2,20,541 Receipt Sl. No. Date Name of the Society District No. Copy Name Name Branch Change Change Challan Address Renewal Certified No./Date Duplicate 1 02410237 01-04-2017 NABAJYOTI RURAL DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Barpeta 200 640/3-3-17 Barpeta 2 02410238 01-04-2017 MISSION TO THE HEARTS OF MILLION Barpeta 130 10894/28-3-17 Barpeta 3 02410239 01-04-2017 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Barpeta 200 2935/9-3-17 Barpeta 02410240 Barpeta 4 01-04-2017 SIPNI SOCIO ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION 100 5856/15-2-17 Barpeta 5 02410241 01-04-2017 DESTINY WELFARE SOCIETY Barpeta 100 5857/15-2-17 Barpeta 08410259 Dhubri 6 01-04-2017 DHUBRI DISTRICT ENGINE BOAT (BAD BADHI) OWNER ASSOCIATION 75 14616/29-3-17 Dispur 7 15411288 03-04-2017 SOCIETY FOR CREATURE KAM(M) 52 40/3-4-17 Dispur 8 15411289 03-04-2017 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE DAKHIN GUWAHATI JATIYA BIDYALAYA KAM(M) 125 15032/30-2-17 Dispur 9 24410084 03-04-2017 UNNATI SIVASAGAR 100 11384/15-3-17 Dispur 10 27410050 03-04-2017 AMGULI GAON MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11836/16-2-17 Dispur 11 27410051 03-04-2017 MANPUR MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11837/15-2-17 Dispur 12 27410052 03-04-2017 ULUBARI MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11835/16-2-17 Dispur 13 15411291 04-04-2017 ST. CLARE CONVENT EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY KAM(M) 100 342/5-4-17 Dispur 14 16410228 04-04-2017 SERAPHINA SEVA SAMAJ KAM(R) 60 343/5-4-17 Dispur 15 16410234 -

Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road

No.24-5/2017-N.M.(Assam) Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11th Floor, Pt. Deendayal Antyodaya Bhawan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-3 Dated : 3v March, 2017 To The Pay and Accounts Officer Ministry of Minority Affairs, 11th Floor, Pt. Deendayal Antyodaya Bhawan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003 Subject: Sanction of Project under Nai Manzil Scheme in the State of Assam to be implemented by Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam-782435 - Release of 1st installment (30%) of training cost for additional 120 trainees during 2016-17 Sir, In continuation of this Ministry's Sanction Order of even number dated 24.03.2017, I am directed to convey the approval of the President of India to sanction additional 120 Nos. of trainees under the Nai Manzil Project to Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil All Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam -782435 for the Assam State. The total number of trainees has been enhanced to 970 Nos. from 850 Nos. with this additional allocation. Consequently, the cost of the Project has also been enhanced to Rs. 5,48,05,000/- from Rs. 4,80,25,000/-. This cost ceiling is subject to common norms of Ministry of Skill Development & Entrepreneurship for skill component applicable from time to time. 2. I am also directed to convey the sanction of the President of India for release of Rs. 20,34,000/- ( Rupees twenty lakh and thirty four thousand only) (making total release to Rs. 1,64,41,500/-) for 970 trainees as 1st installment (30%) of Grants-in-aid to 111 Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam -782435 during 2016-17. -

History ABSTRACT Priesthood Among the Misings Tribe of Assam

Research Paper Volume : 2 | Issue : 12 | DecemberHistory 2013 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Priesthood among the Misings tribe of KEYWORDS : Mibu, function, mouth- Assam piece, position, mediator, changing Dr. Ranjit Kaman Asst. professor ,HoD, Deptt. Of History, Chaiduar College , Gohpur, Dist-Sonitpur, Assam, Pin-784168 Mohendra Doley Asst. Professor, Deptt. Of History, H P B Girls’ College, Dist- Golaghat, Assam, Pin- 785621 ABSTRACT In Mising society, the ‘Mibu’ or ‘Mírí’(the traditional priest) performs all sorts of religious rituals as well as ceremonies. The Mibu plays a very significant role in their society. He is the mouthpiece of the people to com- municate their grievance and suffering to the spirits for redress. The Priest is believed to have knowledge of a divination. When he is summoned in case of sickness or temporal distress they consulted omens by rice, egg and rice beer (Poro Apong). Further, he deter- mined kind of Sacrifice to be offered and detect the spirit, whom it is to be offered. The function of a Mibu are varied and multifarious, when he performs Puja and other rituals, he is a priest, when he is attending it he is a spiritual guide. Further, he maintains the great responsibility of keeping records of oral history. In normal life Mibu invokes the blessing of benevolent deities on behalf of the family and the peoples. The Mibu,a priest in their beliefs is a very important person. He is recognized to be a mediator between mankind and supernatural power. In Mising society, Mibu Performs all the works of propitiation and offering of sacrifices while officiating in community socio- religious functions, individual rites connected with life cycle and illness. -

Flags of Asia

Flags of Asia Item Type Book Authors McGiverin, Rolland Publisher Indiana State University Download date 27/09/2021 04:44:49 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/12198 FLAGS OF ASIA A Bibliography MAY 2, 2017 ROLLAND MCGIVERIN Indiana State University 1 Territory ............................................................... 10 Contents Ethnic ................................................................... 11 Afghanistan ............................................................ 1 Brunei .................................................................. 11 Country .................................................................. 1 Country ................................................................ 11 Ethnic ..................................................................... 2 Cambodia ............................................................. 12 Political .................................................................. 3 Country ................................................................ 12 Armenia .................................................................. 3 Ethnic ................................................................... 13 Country .................................................................. 3 Government ......................................................... 13 Ethnic ..................................................................... 5 China .................................................................... 13 Region ..................................................................