“La Storia Mia È Breve”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Group & Listed

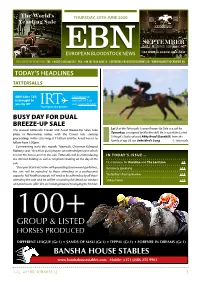

The World's THURSDAY, 25TH JUNE 2020 Yearling Sale SEPTEMBERSALE BEGINS SUNDAY 13 EBN SEPTEMBER.KEENELAND.COM EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • FAX: +44 (0) 1638 666516 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU TODAY’S HEADLINES TATTERSALLS EBN Sales Talk Click here to is brought to contact IRT, or you by IRT visit www.irt.com BUSY DAY FOR DUAL BREEZE-UP SALE The revised Tattersalls Craven and Ascot Breeze-Up Sales take Lot 3 at the Tattersalls Craven Breeze-Up Sale is a colt by Tamarkuz, consigned by Mocklershill. He is out of the Listed place in Newmarket today, with the Craven lots starting St Hugh's Stakes-placed Abby Road (Danehill), from the proceedings in the sales ring at 11:00am and the Ascot horses to family of top US sire Unbridled's Song. © Tattersalls follow from 3:00pm. Commenting early this month, Tattersalls Chairman Edmond Mahony said: “As well as giving buyers an extended period in which to view the horses prior to the sale, Tattersalls will be reintroducing IN TODAY’S ISSUE... live internet bidding as well as telephone bidding on the day of the sale. First winners for Buratino and The Last Lion p5 “On a practical level, in line with prevailing Government guidelines, Relatively Speaking p10 the sale will be restricted to those attending in a professional capacity. Full health protocols will need to be adhered to by all those Yesterday's Racing Review p14 attending the sale and we will be circulating full details to vendors Stakes Fields p20 and purchasers alike. -

MANY Hearts One COMMUNITY Donor Report SPRING 2021 Contents

MANY Hands MANY Hearts One COMMUNITY Donor Report SPRING 2021 Contents 04 ReEnvisioning Critical Care Campaign 06 A Tradition of Generosity 08 Order of the Good Samaritan 18 Good Samaritan of the Year 20 Corporate Honor Roll 24 1902 Club 34 ACE Club 40 Angel Fund 44 Lasting Legacy 48 Gifts of Tribute 50 Special Purpose Funds 54 ReEnvisioning Critical Care Campaign Donors 100% of contributions are used exclusively for hospital projects, programs, or areas of greatest need to better serve the changing healthcare needs of our community. Frederick Health Hospital is a 501(c)(3) not-for-proft organization and all gifts are tax deductible as allowed by law. Message from the President Dear Friends, For over 119 years, members of our community have relied on the staff at Frederick Health to provide care and comfort during their time of need. This has never been more evident than in the past year, as the people of Frederick trusted us to lead the way through the COVID-19 crisis. Driven by our mission to positively impact the well-being of every individual in our community, we have done just that, and I could not be more proud of our healthcare team. Over the past year, all of us at Frederick Health have been challenged in ways we never have been before, but we continue to serve the sick and injured as we always have—24 hours a day, 7 days a week, every day of the year. Even beyond our normal scope of caring for patients, our teams also have undertaken other major responsibilities, including large scale COVID-19 testing and vaccination distribution. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 9/20/06 • PAGE 2 of 5

ALAN PORTER HEADLINE p. 4-5 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 ‘RED’ BLOOMS AGAIN IN BLANDFORD ANOTHER KEESEP SESSION IN THE BOOKS The homebred Red Bloom (GB) (Selkirk) carried A colt by Booklet topped Tuesday=s action at Cheveley Park=s colors to victory in the 2005 G2 Bland- Keeneland September selling to John Brocklebank, ford S. at The Curragh and was back for a repeat per- agent, for $500,000. Out of the formance yesterday. A stalwart of the Sir Michael unraced Wavering Monarch mare Stoute stable over the past four years, she took the G1 Fees Waived, hip 2804 was con- Fillies= Mile in 2002 before finishing third in the follow- signed by Vinery Ltd. The bay ing year=s G1 Coronation S. Last term, she placed in the was bred in Kentucky by G1 Pretty Polly S. here and G1 Nassau S. before annex- Glencrest Farm. Booklet, winner ing this contest. She found the testing conditions at Booklet of the 2002 GI Fountain of York against her when fourth on her seasonal bow in Equi-Photo Youth S., died of colic in 2004. the May 18 G3 Middleton S., but rebounded to finish His first foals are yearlings of third in the latest renewal of the Pretty Polly July 1. 2006. Hip 2630, a filly by Petionville out of the Nijinsky Disappointing again on Deauville=s deep ground when II mare So Unusual, led the way for the fillies, selling third in the G2 Prix Jean Romanet Aug. -

Dove L'uomo È Fascina E La Donna È L'alare

Dove l’uomo è fascina e la donna è l’alare: the Quiet Defiance of Puccini’s La Bohème Parkorn Wangpaiboonkit Oberlin College In stark contrast to the remainder of the standard operatic repertoire, instead of babies thrown into fires, sons in love with their mother-in-law, mystical rings of fire, head-cutting, suicide, self-sacrifice, or spontaneous expiration through excess of emotion, Puccini’s La Bohème presents us with an opera where a sick girl gets sicker and dies. “No one is evil; it is the opera of innocence… - as if there were no responsibility, as if nothing happened other than this great cold, freezing them all, which one of them, a woman, cannot withstand” (Clément 83). More simply put, Bohème ’s plot is “boy meets girl, girl dies” (Berger 109). While this lack of momentous action might make Bohème seem an unlikely candidate for an operatic innovation, I argue that the opera’s quiet insurrection against its genre and tradition becomes apparent when its heroine, Mimi, is closely examined. In constructing Mimi, Puccini has deviated from the expectations of genre, gender, and disease narrative typically found in nineteenth century Italian operas, creating an operatic heroine that escapes the typical dramatic formulations of her predecessors: “She does not do anything. She waters her flowers at the window, she embroiders silk and satin for other people, that is all” (Clément 84). By highlighting these subtle but radical uniqueness in the way Mimi as a heroine is treated by other characters in the opera and by us as an audience, I offer a new reading of Bohème that recognizes the work as an innovative text, “the first Italian opera in which the artificialities of the medium is so little felt” (Budden 180). -

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

La-Boheme-Study-Guide-Reduced.Pdf

VANCOUVER OPERA PRESENTS LA BOHÈME Giacomo Puccini STUDY GUIDE OPERA IN FOUR ACTS By Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, based on Henri Murger’s novel Scènes de la Vie de bohème. In Italian with English Surtitles™ CONDUCTOR Judith Yan DIRECTOR Renaud Doucet QUEEN ELIZABETH THEATRE February 14, 16, 19 & 21at 7:30PM | February 24 at 2PM DRESS REHEARSAL Tuesday, February 12 at 7PM OPERA EXPERIENCE Tuesday, February 19 and 21 at 7:30PM EDUCATION LA BOHÈME VANCOUVER OPERA | STUDY GUIDE LA BOHÈME Giacomo Puccini CAST IN ORDER OF VOCAL APPEARANCE MARCELLO, A PAINTER Phillip Addis RODOLFO, A POET Ji-Min Park COLLINE, A PHILOSOPHER Neil Craighead SCHAUNARD, A MUSICIAN Geoffrey Schellenberg BENOIT, A LANDLORD J. Patrick Raftery MIMI, A SEAMSTRESS France Bellemare PLUM SELLER Wade Nott PARPIGNOL, A TOY SELLER William Grossman MUSETTA, A WOMAN OF THE LATIN QUARTER Sharleen Joynt ALCINDORO, AN ADMIRER OF MUSETTA J. Patrick Raftery CUSTOMS OFFICER Angus Bell CUSTOMS SERGEANT Willy Miles-Grenzberg With the Vancouver Opera Chorus as habitués of the Latin Quarter, students, vendors, soldiers, waiters, and with the Vancouver Opera Orchestra. SCENIC DESIGNER / COSTUME DESIGNER André Barbe CHORUS DIRECTOR/ ASSOCIATE CONDUCTOR Leslie Dala CHILDREN’S CHORUS DIRECTOR / PRINCIPAL RÉPÉTITEUR Kinza Tyrrell LIGHTING DESIGNER Guy Simard WIG DESIGNER Marie Le Bihan MAKEUP DESIGNER Carmen Garcia COSTUME COORDINATOR Parvin Mirhady MUSICAL PREPARATION Tina Chang, Perri Lo* STAGE MANAGER Theresa Tsang ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Peter Lorenz ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGERS Marijka Asbeek Brusse, Michelle Harrison ASSISTANT LIGHTING DESIGNER Sara Smith ENGLISH SURTITLE™ TRANSLATIONS David Edwards Member of the Yulanda M. Faris Young Artist Program* The performance will last approximately 2 hours and 18 minutes. -

Puccini Il Tabarro

Puccini Il Tabarro MELODY MOORE · BRIAN JAGDE · LESTER LYNCH MDR LEIPZIG RADIO CHOIR · DRESDNER PHILHARMONIE MAREK JANOWSKI Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Giorgetta Melody Moore, Soprano Il Tabarro (1918) Michele Lester Lynch, Baritone Opera in one act Luigi Brian Jagde, Tenor Libretto: Giuseppe Adami Un venditore di canzonette Khanyiso Gwenxane, Tenor Frugola Roxana Constantinescu, Mezzo-soprano 1 Introduzione 2. 02 Tinca Simeon Esper, Tenor 2 O Michele? (Giorgetta, Michele, Scaricatori) 2. 07 Talpa Martin-Jan Nijhof, Bass 3 Si soffoca, padrona! (Luigi, Giorgetta, Tinca, Talpa) 2. 11 Voce di Sopranino & 4 Ballo con la padrona!(Tinca, Luigi, Giorgetta, Talpa, Michele) 1. 35 Un’amante Joanne Marie D’Mello, Soprano 5 Perché? (Giorgetta, Un venditore di canzonette, Michele, Midinettes) 3. 21 Voce di Tenorino & 6 Conta ad ore le giornate (Midinettes, Frugola, Giorgetta) 3. 56 Un amante Yongkeun Kim, Tenor 7 To’! guarda la mia vecchia! (Talpa, Frugola, Michele, Luigi, Tinca) 1. 21 8 Hai ben raggione; meglio non pensare (Luigi) 2. 22 MDR Leipzig Radio Choir 9 Segui il mio esempio (Tinca, Talpa, Frugola, Giorgetta, Luigi) 2. 32 Chorus Master: Jörn Hinnerk Andresen 10 Belleville è il suolo e il nostro mondo! (Giorgetta, Luigi) 2. 29 11 Adesso ti capisco (Frugola, Talpa, Luigi, Voce di Sopranino, Voce di Tenorino) 2. 22 Dresdner Philharmonie 12 O Luigi! Luigi! (Giorgetta, Luigi) 1. 30 Concertmaster: Wolfgang Hentrich 13 Come? Non sei andato? (Michele, Luigi, Giorgetta) 1. 13 Assistant Conductor: Andreas Henning 14 Dimmi: perché gli hai chiesto di sbarcarti a Rouen? (Giorgetta, Luigi, Michele) 4. 36 15 Perché non vai a letto? (Michele, Giorgetta) 7. -

San Diego Symphony Orchestra Puccini's

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA PUCCINI’S GLORIOUS MASS A Jacobs Masterworks Concert Speranza Scappucci, conductor March 22 and 23, 2019 FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN Symphony No. 88 in G Major Adagio – Allegro Largo Menuetto: Allegretto Allegro con spirito INTERMISSION GIACOMO PUCCINI Messa di Gloria Kyrie Gloria Credo Sanctus – Benedictus Agnus Dei Leonardo Capalbo, tenor Daniel Okulitch, baritone Michael Sumuel, bass San Diego Master Chorale Symphony No. 88 in G Major FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN Born March 31, 1732, Rohrau (Austria) Died May 31, 1809, Vienna Haydn spent 30 years as Kapellmeister to the Esterhazy family at their estates on the plain east of Vienna. If, as Haydn observed, that isolation forced him “to become original,” it also had the unfortunate effect of cutting him off from mainstream European musical life. Only gradually did his extraordinary achievement with the symphony and string quartet become known to musicians across Europe. By the 1780s, when Haydn was in his third decade with the Esterhazys, his prince finally allowed him to accept commissions from outside, and suddenly he had many requests for symphonies. For a concert series in Paris, he wrote his Symphonies No. 82-87 (known as the “Paris symphonies”), and for his two trips to England he composed his final twelve symphonies (Nos. 93-104), inevitably known as the “London symphonies.” Between these two great cycles, Haydn composed five individual symphonies, probably all of them written with Parisian audiences in mind. He wrote the first two, Nos. 88 and 89, in 1787, at exactly the same moment Mozart was composing Don Giovanni in Vienna. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

Biography: Fabio Armiliato

Biography: Fabio Armiliato Internationally renewed tenor Fabio Armiliato is acclaimed by the public thanks to his unique vocal style, his impressive upper register and his dramatic abilities and charisma that infuses in his characters. He made his opera debut as Gabriele Adorno in Simon Boccanegra in his hometown Genoa, where he graduated at the Conservatory Niccolo Paganini, after which his career set off leading him to address many important roles for his register in the most prestigious theatres in the world. In 1993 debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York with Il Trovatore, followed by Aida, Cavalleria Rusticana, Don Carlo, Simon Boccanegra, Tosca, Fedora, Madama Butterfly. Especially his performance of Andrea Chènier at the Met is considered one of his most iconic roles, receiving the proclamation from the critics of “best Chénier of our times”. Equally importance Fabio Armiliato gave to the role of Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, sung amongst others at La Scala in Milan, at the Gran Teatre del Liceu and the New National Theatre in Tokyo. During the period from 1990 to 1996, he performed in the Opera of Antwerp on a cycle dedicated to Giacomo Puccini, in production directed by Robert Carsen interpreting Tosca, Don Carlo and Manon Lescaut. Armiliato is a refined interpreter of Mario Cavaradossi in Tosca with more than 150 performances of the title, he has been acclaimed in this role in the most prestigious Opera Houses including La Scala in Milan, conducted by Lorin Maazel, and the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden in London under the baton of Antonio Pappano in 2006. -

View the Program!

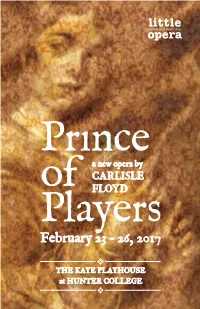

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

La Bohème Opera in Four Acts Music by Giacomo Puccini Italian Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica Afterscènes Da La Vie De Bohème by Henri Murger

____________________ The Indiana University Opera Theater presents as its 395th production La Bohème Opera in Four Acts Music by Giacomo Puccini Italian Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica AfterScènes da la vie de Bohème by Henri Murger David Effron,Conductor Tito Capobianco, Stage Director C. David Higgins, Set Designer Barry Steele, Lighting Designer Sondra Nottingham, Wig and Make-up Designer Vasiliki Tsuova, Chorus Master Lisa Yozviak, Children’s Chorus Master Christian Capocaccia, Italian Diction Coach Words for Music, Supertitle Provider Victor DeRenzi, Supertitle Translator _______________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Ninth Saturday Evening, November Tenth Friday Evening, November Sixteenth Saturday Evening, November Seventeenth Eight O’Clock Two Hundred Eighty-Fourth Program of the 2007-08 Season music.indiana.edu Cast (in order of appearance) The four Bohemians: Rodolfo, a poet. Brian Arreola, Jason Wickson Marcello, a painter . Justin Moore, Kenneth Pereira Colline, a philosopher . Max Wier, Miroslaw Witkowski Schaunard, a musician . Adonis Abuyen, Mark Davies Benoit, their landlord . .Joseph “Bill” Kloppenburg, Chaz Nailor Mimi, a seamstress . Joanna Ruzsała, Jung Nan Yoon Two delivery boys . Nick Palmer, Evan James Snipes Parpignol, a toy vendor . Hong-Teak Lim Musetta, friend of Marcello . Rebecca Fay, Laura Waters Alcindoro, a state councilor . Joseph “Bill” Kloppenburg, Chaz Nailor Customs Guard . Nathan Brown Sergeant . .Cody Medina People of the Latin Quarter Vendors . Korey Gonzalez, Olivia Hairston, Wayne Hu, Kimberly Izzo, David Johnson, Daniel Lentz, William Lockhart, Cody Medina, Abigail Peters, Lauren Pickett, Shelley Ploss, Jerome Sibulo, Kris Simmons Middle Class . Jacqueline Brecheen, Molly Fetherston, Lawrence Galera, Chris Gobles, Jonathan Hilber, Kira McGirr, Justin Merrick, Kevin Necciai, Naomi Ruiz, Jason Thomas Elegant Ladies .