Exploring the Effects of Colonialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the West Was Once Tour from Phoenix | 4-Days, 3-Nights

HOW THE WEST WAS ONCE TOUR FROM PHOENIX | 4-DAYS, 3-NIGHTS BISBEE • TOMBSTONE • TUBAC • TUCSON Tombstone TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Travel back to the 19th century, a time when Why DETOURS? cowboy rivals held gunfights in the streets of Tombstone and outlaws made the west wild. • Small group tour with up to 12 passengers – no crowds! • The best historical lodging available – no lines! Tales of conquest and survival come to life on a 4-day, 3-night • Custom touring vehicles with comfortable, individual guided tour from Phoenix. This western trip of a lifetime captain’s chairs, plenty of legroom, and large picture explores several historic Southern Arizona locations like Fort windows to enjoy the views Bowie, San Xavier del Bac mission, the Amerind Museum, and the old mining town of Bisbee. Small group tour • Expert guides who are CPR and First Aid certified dates coincide with Wyatt Earp Days or Helldorado Days in Tombstone for a truly immersive experience. Tour Dates & Pricing Fall 2020: November 6th - 9th $1,195 per person for double occupancy $1,620 per person for single occupancy PACKAGES START AT $1,195* * Double Occupancy. Includes guided tour, lodging, some meals, entrance fees, and taxes BOOK NOW AT DETOURSAMERICANWEST.COM/HWWOT Fort Bowie TOUR ITINERARY DAY ONE DAY TWO the most beautiful vineyards in the region for a flight of wine tasting. After enjoying the After an early breakfast, our tour heads Known as the “Town Too Tough to Die”, delicious drinks, we continue west to Tubac, south into the heart of Arizona’s Sonoran Tombstone was home to famous outlaws, where an incredible collection of artists and Desert, surrounded by towering saguaro, pioneers, miners, cattlemen, and cowboys craftspeople have created the world famous volcanic peaks, and endless horizons. -

Have Gun, Will Travel: the Myth of the Frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall

Feature Have gun, will travel: The myth of the frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall Newspaper editor (bit player): ‘This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, we print the legend’. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (dir. John Ford, 1962). Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott): ‘You know what’s on the back of a poor man when he dies? The clothes of pride. And they are not a bit warmer to him dead than they were when he was alive. Is that all you want, Steve?’ Steve Judd (Joel McCrea): ‘All I want is to enter my house justified’. Ride the High Country [a.k.a. Guns in the Afternoon] (dir. Sam Peckinpah, 1962)> J. W. Grant (Ralph Bellamy): ‘You bastard!’ Henry ‘Rico’ Fardan (Lee Marvin): ‘Yes, sir. In my case an accident of birth. But you, you’re a self-made man.’ The Professionals (dir. Richard Brooks, 1966).1 he Western movies that from Taround 1910 until the 1960s made up at least a fifth of all the American film titles on general release signified Lee Marvin, Lee Van Cleef, John Wayne and Strother Martin on the set of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance escapist entertainment for British directed and produced by John Ford. audiences: an alluring vision of vast © Sunset Boulevard/Corbis open spaces, of cowboys on horseback outlined against an imposing landscape. For Americans themselves, the Western a schoolboy in the 1950s, the Western believed that the western frontier was signified their own turbulent frontier has an undeniable appeal, allowing the closing or had already closed – as the history west of the Mississippi in the cinemagoer to interrogate, from youth U. -

Nebraska's Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World Full Citation: William E Deahl Jr, “Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World,” Nebraska History 49 (1968): 282-297 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1968Entertainment.pdf Date: 11/23/2015 Article Summary: Buffalo Bill Cody and Dr. W F Carver were not the first to mount a Wild West show, but their opening performances in 1883 were the first truly successful entertainments of that type. Their varied acts attracted audiences familiar with Cody and his adventures. Cataloging Information: Names: William F Cody, W F Carver, James Butler Hickok, P T Barnum, Sidney Barnett, Ned Buntline (Edward Zane Carroll Judson), Joseph G McCoy, Nate Salsbury, Frank North, A H Bogardus Nebraska Place Names: Omaha Wild West Shows: Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition -

The Reel Latina/O Soldier in American War Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-26-2012 12:00 AM The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema Felipe Q. Quintanilla The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Rafael Montano The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Felipe Q. Quintanilla 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Quintanilla, Felipe Q., "The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 928. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/928 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REEL LATINA/O SOLDIER IN AMERICAN WAR CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Hispanic Studies The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ -

Frontier Identity in Cultural Events in Holmes County, Florida

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Frontier Identity in Cultural Events in Holmes County, Florida Tyler Dawson Keith Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Keith, Tyler Dawson, "Frontier Identity in Cultural Events in Holmes County, Florida" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 163. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/163 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER IDENTITY IN CULTURAL EVENTS IN HOLMES COUNTY, FLORIDA A Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements For the degree of Master of Arts In the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by TYLER D. KEITH May 2011 Copyright Tyler D. Keith 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Holmes County, Florida plays host to several cultural events that perpetuate a frontier identity for its citizens. These events include the dedication of a homesteading cabin, which serves as the meeting place for other ―pioneer days‖ events; ―Drums along the Choctawhatchee‖, an event put on by a local Creek Indian tribe that celebrates the collaborative nature of pioneer and Native Americans; the 66th annual North West Florida Championship Rodeo; and a local fish-fry. Each of these events celebrates the frontier identity of the county in unique and important ways. Using the images of the frontier created by William ―Buffalo Bill‖ Cody‘s Wild West show and the ideas championed by Fredrick Jackson Turner in his famous essay ―The Importance of the Frontier in American History‖ as models, Holmes County constructs its own frontier image through the celebration of these combined cultural events. -

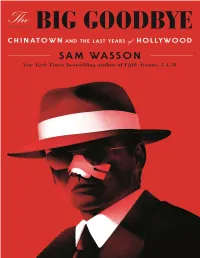

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

La Città Che Sale

LUNEDÌ 24 MARTEDÌ 25 Il sogno dell’architetto Le mani sulla città: speculazione edilizia, criminalità organizzata e il malessere delle periferie ore 16 La fonte meravigliosa di King Vidor (Usa 1949) ore 16 Accattone ore 18,30 Manhattan di Pier Paolo Pasolini (Italia 1961) di Woody Allen (Usa 1979) ore 18,30 Chinatown di Roman Polanski (USA 1974) Interventi: Sergio Arecco copia restaurata (storico-critico cinematografico) Interventi: Sergio Arecco ore 21,15 Caro diario (ep. In Vespa) LA di Nanni Moretti (It-Fr 1993) ore 21,15 Take Five Medianeras di Guido Lombardi (Italia 2013) di Gustavo Taretto anteprima (Arg-Sp-Ger 2011) Largo Baracche CITTÀ anteprima di Gaetano Di Vaio (Italia 2014) anteprima Interventi: Giovanni Maffei Cardellini CHE (architetto urbanista), Augusto Interventi: Gaetano Di Vaio Mazzini (architetto urbanista) (attore-regista-produttore), Guido Lombardi (regista) SALE CAMPOECONTROCAMPO.IT A cura di Claudio Carabba e L’IMMAGINARIO SIENA CINEMA Giovanni M. Rossi URBANO 24–25 NUOVO DEL CINEMA NOVEMBRE PENDOLA 2014 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE 16.30 16,00 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE 16.30 18,30 LUNEDÌGIOVEDÌ 24 22 NOVEMBRE MARZO, ORE – ORE16.30 21,15 GIOVEDÌLUNEDÌ 2422 NOVEMBREMARZO, ORE – 16.30ORE 21,15 La fonte meravigliosa Manhattan In Vespa (ep. di Caro diario) Medianeras The Fountainhead Innamorarsi a Buenos Aires Di KING VIDOR (Usa 1949, BN, 114’ - v.o. sott. it.) Di WOODY ALLEN (Usa 1979, BN, 96’ - v.o. sott. it.) Di NANNI MORETTI (Italia-Francia 1993, COL, 25’) Di GUSTAVO TARETTO (Argentina-Spagna-Germania 2011, COL, 95’) Soggetto: dal romanzo omonimo di Ayn Rand. -

Arizona, Southwestern and Borderlands Photograph Collection, Circa 1873-2011 (Bulk 1920-1970)

Arizona, Southwestern and Borderlands Photograph collection, circa 1873-2011 (bulk 1920-1970) Collection Number: Use folder title University of Arizona Library Special Collections Note: Press the Control button and the “F” button simultaneously to bring up a search box. Collection Summary Creator: Various sources Collection Name: Arizona, Southwestern and Borderlands Photograph collection Inclusive Dates: 1875-2011 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1920-1970) Physical Description: 95 linear feet Abstract: The Arizona, Southwestern and Borderland photograph collection is an artificially created collection that consists of many folders containing photographs, from various sources, of Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico arranged by topics including places, people, events and activities, and dating from about 1875 to the present, but mostly after 1920. Formats include postcards, stereographs, cartes-de-visite, cabinet cards, cyanotypes, view books, photograph albums, panoramas and photoprints. Collection Number: Use folder title Language: Materials are in English and Spanish. Repository: University of Arizona Libraries, Special Collections University of Arizona PO Box 210055 Tucson, AZ 85721-0055 Phone: 520-621-6423 Fax: 520-621-9733 URL: http://speccoll. library.arizona.edu/ E-Mail: [email protected] Historical Note The Photograph subject files were created and added to by Special Collections staff members, over the years, from donations received from various sources, in order to provide subject access to these photographs within Special Collections holdings. Scope and Content Note The files generally fall into the categories of Arizona and New Mexico cities and towns, military posts, and other places; Tucson, Ariz.; Indians of Arizona, New Mexico and Mexico; Mexico; and individual people. Formats include postcards, stereographs, cartes-de-visite, cabinet cards, cyanotypes, viewbooks, and photoprints. -

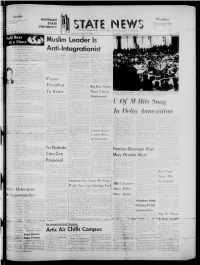

Michigan State University, R

I n s id e a*otioft tp«l< for (tv- MICHIGAN fp rather ¡s page »• . ly w ith tem o * ft STATI 5 dff<3ft4i obov u n iv e r s it y r- »- * . • S 1 Edited by-Stadents f o r the M i tate University Communitj i 54 NTo. 82 - East Lansing, Mlchigi 'hursday, January 24, 1963 forili News at a Glance Muslim Leader Is By AP and UPI Wire Service« a York For Newspaper Strike Tali Anti-lntegrationist rÉrnffiÉfi ax Reduction Program Tt VASH1NCTON d a special uction progn t I reads Wayne§/ President Soapy’ Big Boy Chain To Retire Plans 2 Area M USLIM L H ADER--Malcolm X pteoches the in the Ki*t la y . 0 « doctrine of Mu slim to an over-capacity crowd tended the Restaurants rre Of Clemson Cl U Of M f lits Snag iid VVedne; ion calling here was- In Delta Annexation C». 2 Grads Receive . > ..A» ■ h i Coveted tiffany Art Fellowships igo9*d To Greek To Debate tfanes call Franco-German Pact Con-Con May Divide West Proposal in Ax Murder after she dl< W fwi ritt#w4 Wai B e e r f a n s felt* i ! ly System Plans Uniform Ti fhe State Univcr si tv Trustee F i n d A l l y 000 sti ¡Students Go Loop De Loop ¡ I n C a p i t o l M H A L If ith Nejk) C ar-C huting Fadi Hades Determine O n >SS P olicy net of New England co 100 rnoid, 23, of Windsor O n c e A g a i n 'S L 1-î lohn Dorspv. -

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index Revised and edited by Kristina L. Southwell Associates of the Western History Collections Norman, Oklahoma 2001 Boxes 104 through 121 of this collection are available online at the University of Oklahoma Libraries website. THE COVER Michelle Corona-Allen of the University of Oklahoma Communication Services designed the cover of this book. The three photographs feature images closely associated with Walter Stanley Campbell and his research on Native American history and culture. From left to right, the first photograph shows a ledger drawing by Sioux chief White Bull that depicts him capturing two horses from a camp in 1876. The second image is of Walter Stanley Campbell talking with White Bull in the early 1930s. Campbell’s oral interviews of prominent Indians during 1928-1932 formed the basis of some of his most respected books on Indian history. The third photograph is of another White Bull ledger drawing in which he is shown taking horses from General Terry’s advancing column at the Little Big Horn River, Montana, 1876. Of this act, White Bull stated, “This made my name known, taken from those coming below, soldiers and Crows were camped there.” Available from University of Oklahoma Western History Collections 630 Parrington Oval, Room 452 Norman, Oklahoma 73019 No state-appropriated funds were used to publish this guide. It was published entirely with funds provided by the Associates of the Western History Collections and other private donors. The Associates of the Western History Collections is a support group dedicated to helping the Western History Collections maintain its national and international reputation for research excellence. -

April 2, 1987

China exchange agreements expand More University disciplines involved oncordia's recently with The People's Republic has laborative research and student signed electrical engi already succeeded in serving as training, Concordia faculty C neering and computer "a vehicle for Concordia to members did not receive one .s cience agreement with th~ establish itself, alongside other penny of those funds . Nanjing Institute of Technolo large Canadian universities, as The China initiative should gy may have stolen all the a full participant in govern begin to change all that, Whyte headlines, but the University's ment-funded international said. For a variety of reasons - ongoing China initiative development programs," he not least of which is the innova involves disciplines in numer said. tive nature of the linkage with ous University departments. Whyte noted that in 1985-86 NIT - "it is unquestionably In a report to Senate last alone, the Canadian govern the strongest project Con 1riday, Vice-Rector, Academic, ment allocated $22 million to cordia has ever had for obtain :<'rancis Whyte said that a total Canadian universities for inter ing very substantial Canadian of six agreements have been national academic activities government funding in the area negotiated with universities in involving China. Despite the of international development the People's Republic of Chi fact Concordia is very active in activities." The magic offilm. See stories on movie stars and a film about a na. Four were signed during international exchanges, col- See CHINA page 2 woman guerrilla, page 4. February and March; the other two will likely be signed during upcoming visits to Concordia by three delegations from The Of trusteeship, funding & vandalism People's Republic. -

Horses in the Southwest Tobi Taylor and William H

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTHWEST CONTINUE ON TO THE NEXT PAGE FOR YOUR magazineFREE PDF (formerly the Center for Desert Archaeology) is a private 501 (c) (3) nonprofit organization that explores and protects the places of our past across the American Southwest and Mexican Northwest. We have developed an integrated, conservation- based approach known as Preservation Archaeology. Although Preservation Archaeology begins with the active protection of archaeological sites, it doesn’t end there. We utilize holistic, low-impact investigation methods in order to pursue big-picture questions about what life was like long ago. As a part of our mission to help foster advocacy and appreciation for the special places of our past, we share our discoveries with the public. This free back issue of Archaeology Southwest Magazine is one of many ways we connect people with the Southwest’s rich past. Enjoy! Not yet a member? Join today! Membership to Archaeology Southwest includes: » A Subscription to our esteemed, quarterly Archaeology Southwest Magazine » Updates from This Month at Archaeology Southwest, our monthly e-newsletter » 25% off purchases of in-print, in-stock publications through our bookstore » Discounted registration fees for Hands-On Archaeology classes and workshops » Free pdf downloads of Archaeology Southwest Magazine, including our current and most recent issues » Access to our on-site research library » Invitations to our annual members’ meeting, as well as other special events and lectures Join us at archaeologysouthwest.org/how-to-help In the meantime, stay informed at our regularly updated Facebook page! 300 N Ash Alley, Tucson AZ, 85701 • (520) 882-6946 • [email protected] • www.archaeologysouthwest.org Archaeology Southwest Volume 18, Number 3 Center for Desert Archaeology Summer 2004 Horses in the Southwest Tobi Taylor and William H.