Indiana Law Review Volume 43 2010 Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

Jack and Ann Arnold

JACK AND ANN ARNOLD 32 ROCKY KNOLL Remember the “Pool Guy” episode on Seinfeld? The one where the pool-guy, Jerry’s self-professed “best friend,” HAD to squeeze in between Jerry and Kramer in the movie theater even though they had purposely left one seat between them for buffer? For Jerry, that was the last straw that made him cut ties with the pool guy once and for all. But that was 1995, and the movie was Firestorm. For Jack and Ann, it was one year before that, and the movie was In the Name of the Father. At Edwards Island 7 Cinema. And THIS story has a happy ending. On a Saturday evening in March of 1994, Ann (then) Lombardi was in a pensive mood. Her close friend had just passed away. Her happy childhood in Waterbury, Connecticut, seemed like a distant memory. Even moving to Orange County in her early 20’s because the soot from the factories and the wet, cold winters weren’t helping her asthmatic son. It was all starting to feel like a bad dream. She was in a good place then career-wise, having worked for Bank of America, moving up from an hourly teller all the way up to a corporate trainer, who trained bank/corporate officers all over the country. But what she needed on that particular evening was some peace and quiet. What better way was there to mourn a friend’s passing than to watch a movie about the IRA? She got to the theater early to get the best seat in the house. -

Monday 12/14/2020 Tuesday 12/15/2020 Wednesday 12/16/2020

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12/14/2020 12/15/2020 12/16/2020 12/17/2020 12/18/2020 12/19/2020 12/20/2020 4:00 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Dish Nation TMZ Live Weekend Marketplace 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 4:00 - 4:30 3:30 - 4:30 3:00 - 5:00 4:30 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Personal Injury Court Personal Injury Court (OTO) 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 4:30 - 5:00 5:00 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program PaidPatch Program v Miller Bell Paidv Young Program & Jones MyDestination.TV 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:00 - 5:30 5:30 am Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program Paid Program The American Athlete 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 5:30 - 6:00 6:00 am Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Couples Court with the Xploration Awesome Live Life and Win! Cutlers Cutlers Cutlers Cutlers Cutlers Planet 6:00 - 6:30 6:30 am Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Protection6:00 - 6:30 Court Elizabeth6:00 - Stanton's 6:30 KarateTeen Kid, Kids Beating News the Schall6:30 v. -

LEASE AGREEMENT the Parties Agree As Follows: Landlord: Address for Notices: Tenant: Address:

® 313— Seasonal short term lease: plain English: furnished or unfurnished, 8-15 © 2015 by BlumbergExcelsior, Inc., Publisher, NYC 11241 www.blumberg.com LEASE AGREEMENT The parties agree as follows: DATE OF THIS LEASE: PARTIES TO THIS LEASE: Landlord: Address for notices: Tenant: Address: TERM: 1. The Term of this Lease shall be years months: beginning ending PREMISES 2. RENTED: USE OF 3. The Premises may be used as a living place for persons only. PREMISES: RENT: 4. The rent is payable as follows: Landlord need not give Tenant notice to pay rent. Tenant must pay the rent in full and not subtract any amount from it. SECURITY: 5. Tenant has given/ Landlord $ as security. If Tenant fully complies with all of the terms of this Lease Landlord will return the security after the Term ends. If Tenant does not fully comply with the terms of this Lease, Landlord may use the security to pay amounts owed by Tenant, including damages. UTILITIES AND 6. Tenant must pay for the following additional utilities and services when billed: SERVICES: Long distance telephone service. Pay-per-view and downloaded cable, dish and similar services. A cleaning deposit of $ is required prior to the commencement of the Term. This deposit will be refunded if the Premises are left in clean condition. If cleaning expenses must be incurred by Lessor to restore the Premises to the condition they were in at the commencement of the Term, the amount necessary for restoration will be deducted from the cleaning deposit and the balance, if any, will be refunded to Lessee. -

The Culture of Post-Narcissism

THE CULTURE OF POST-NARCISSISM The Culture of Post-Narcissism Post-teenage, Pre-midlife Singles Culture in Seinfeld, Friends, and Ally – Seinfeld in Particular MICHAEL SKOVMAND In a recent article, David P. Pierson makes a persuasive case for considering American television comedy, and sitcoms in particular, as ‘Modern Comedies of Manners’. These comedies afford a particular point of entry into contemporary mediatised negotiations of ‘civility’, i.e. how individual desires and values interface with the conventions and stand- ards of families, peer groups and society at large. The apparent triviality of subject matter and the hermetic appearance of the groups depicted may deceive the unsuspecting me- dia researcher into believing that these comedies are indeed “shows about nothing”. The following is an attempt to point to a particular range of contemporary American televi- sion comedies as sites of ongoing negotiations of behavioural anxieties within post-teen- age, pre-midlife singles culture – a culture which in many aspects seems to articulate central concerns of society as a whole. This range of comedies can also be seen, in a variety of ways, to point to new ways in which contemporary television comedy articu- lates audience relations and relations to contemporary culture as a whole. American television series embody the time-honoured American continental dicho- tomy between the West Coast and the East Coast. The West Coast – LA – signifies the Barbie dolls of Baywatch, and the overgrown high school kids of Beverly Hills 90210. On the East Coast – more specifically New York and Boston, a sophisticated tradition of television comedy has developed since the early 1980s far removed from the beach boys and girls of California. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Šárka Tripesová The Anatomy of Humour in the Situation Comedy Seinfeld Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Šárka Tripesová ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. for the invaluable guidance he provided me as a supervisor. Also, my special thanks go to my boyfriend and friends for their helpful discussions and to my family for their support. iii Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SEINFELD AS A SITUATION COMEDY 3 2.1 SEINFELD SERIES: THE REALITY AND THE SHOW 3 2.2 SITUATION COMEDY 6 2.3 THE PROCESS OF CREATING A SEINFELD EPISODE 8 2.4 METATHEATRICAL APPROACH 9 2.5 THE DEPICTION OF CHARACTERS 10 3 THE TECHNIQUES OF HUMOUR DELIVERY 12 3.1 VERBAL TECHNIQUES 12 3.1.1 DIALOGUES 12 3.1.2 MONOLOGUES 17 3.2 NON-VERBAL TECHNIQUES 20 3.2.1 PHYSICAL COMEDY AND PANTOMIMIC FEATURES 20 3.2.2 MONTAGE 24 3.3 COMBINED TECHNIQUES 27 3.3.1 GAG 27 4 THE METHODS CAUSING COMICAL EFFECT 30 4.1 SEINFELD LANGUAGE 30 4.2 METAPHORICAL EXPRESSION 32 4.3 THE TWIST OF PERSPECTIVE 35 4.4 CONTRAST 40 iv 4.5 EXAGGERATION AND CARICATURE 43 4.6 STAND-UP 47 4.7 RUNNING GAG 49 4.8 RIDICULE AND SELF-RIDICULE 50 5 CONCLUSION 59 6 SUMMARY 60 7 SHRNUTÍ 61 8 PRIMARY SOURCES 62 9 REFERENCES 70 v 1 Introduction Everyone as a member of society experiences everyday routine and recurring events. -

Endurance Runner Is New U.S. Citizen

Saints roll Pirates Annual car show Native Sons show off cars, trucks, St. Helena blanks Drake, 52-0 SPORTS, PAGE B1 Jeeps & tractors SPOTLIGHT, PAGE B3 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2019 | sthelenastar.com | Published in the Heart of Napa Valley Since 1874 Family seeks help with vet bill after dog hit by car Callie, a 4-year-old German was for $13,200, which doesn’t Vet bill is $13,200; short-haired pointer, is expected include the weekly checkups and Callie’s family asking to recover, having undergone physical therapy she will need to one surgery to repair the inter- recover. drivers to slow down nal damage and another surgery “It’s been an amazing re- to fi x her broken leg. She came sponse,” said Autumn Anderson, JESSE DUARTE home on Saturday, six days after her owner. “I never expected we [email protected] her injury. would have this much help. The A St. Helena family is asking As of Wednesday morning, online German short-haired drivers to slow down and seeking a GoFundMe campaign called pointer community has rallied SUBMITTED PHOTO help with vet bills of more than “Help Callie the Dog, Hit and around her.” Callie, a 4-year-old German short-haired pointer, suff ered major injuries after $13,000 after their dog was se- Run Victim” had raised $6,043 being hit by a driver who left the scene. riously injured in a hit-and-run. to pay her vet bills. The fi rst bill Please see DOG, Page A2 Public to Endurance runner vote on open space, not is new U.S. -

A Mojave Desert Memoir a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satisfaction Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Suicide, Watch: A Mojave Desert Memoir A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Ruth Marie Nolan December 2014 Thesis Committee: Professor David L. Ulin, Co-Chairperson Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson Professor Emily Rapp Copyright by Ruth Marie Nolan 2014 The Thesis of Ruth Marie Nolan is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I must first thank my wonderful committee members who always gave me insightful comments regarding this novel. I want to thank my parents, Beverly and Joseph Nolan; my brother, John Nolan; my daughter Tarah Templin and son-in-law Alex Templin, and my grandson, Baby Simon Templin. Thanks also to my amazing professors and guides at UCR, who led me along the writing process in completing my thesis: Tod Goldberg, David L. Ulin, Emily Rapp, Mary Yukari Waters, Elizabeth Crane, Rob Roberge, Deanne Stillman, and many others who teach and lecture in the program. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Section 1- Spring Break 5 Section 2- Valley of Fire 73 Section 3- Excavating the Lost City 113 v "The great Creator told us, 'I'm going to teach you these songs, but before I teach you these songs, I'm going to break your heart.'" - Larry Eddy (Chemehuevi Indian Singer) “Closure is bullshit, and I would love to find the man who invented closure and shove a giant closure plaque up his ass” – James Ellroy (author of My Dark Places) “An archaeological feature at a site fills up as the waters of Lake Mead begin to claim the Lost City sites. -

Quirk Books Summer Reads, Curated by Planet Quirk!

This sampler book © 2012 by Quirk Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-59474-633-8 (e-book) Bedbugs copyright © 2011 by Ben H. Winters Pride and Prejudice and Zombies copyright © 2009 by Quirk Productions, Inc. Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children copyright © 2011 by Ransom Riggs Night of the Living Trekkies copyright © 2010 by Kevin David Anderson Taft 2012 copyright © 2012 by Jason Heller The Last Policeman copyright © 2012 by Ben H. Winters Quirk Books 215 Church St. Philadelphia, PA 19106 CONTENTS Introduction ................................. 4 Bedbugs..................................... 5 Pride and Prejudice and Zombies ................. 43 Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children ........ 106 Night of the Living Trekkies ..................... 186 Taft 2012 ................................... 259 The Last Policeman............................ 327 Thank you for downloading Quirk Books Summer Reads, curated by Planet Quirk! Planet Quirk is a world of 99.4% pure imagination (and 0.6% evil genius). It’s a community where you can get your inner geek on. We offer advice on pairing the perfect beer with your favorite comic books. We compose poetry about Harry Potter. We share our favorite Etsy geek crafts. We give away cool stuff and much, much more. Here we’ve rounded up some of the best fiction that Quirk Books has to offer. So if you like to geek out over any kind of sci-horror- fantasy-book-game-film-comics fandom, just pull up a captain’s chair, crack open this sampler, and stay as long as you like. -

Sydney Program Guide

10/23/2020 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=08-Nov-20&psEndDate=1… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 08th November 2020 06:00 am Charmed (Rpt) CC PG We All Scream For Ice Cream Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes The sisters investigate a mysterious Ice Cream Van that abducts children. However, the evil may not be what they initially suspect. Starring: Shannen Doherty, Alyssa Milano, Holly Marie Combs 07:00 am Friends (Rpt) CC PG The One With The Ick Factor Monica finds out more than she wants to know about her latest love. Chandler's friends at work treat him differently since his promotion and Ross' ex-wife goes into labor. Starring: David Schwimmer, Jennifer Aniston, Matthew Perry, Courteney Cox, Matt LeBlanc, Lisa Kudrow 07:30 am Friends (Rpt) CC PG The One With The Birth When Carol gives birth, Ross and Susan almost miss the event and Joey befriends an unmarried pregnant woman. Starring: David Schwimmer, Jennifer Aniston, Matthew Perry, Courteney Cox, Matt LeBlanc, Lisa Kudrow Guest Starring: Leah Remini 08:00 am Rules Of Engagement (Rpt) CC PG The Four Pillars Sexual References WS Audrey convinces Jeff to go to couple's therapy; meanwhile, Russell tries to get over his crush on Timmy's bride-to-be and Adam attempts to take a non-cheesy engagement photo with Jen. Starring: David Spade, Patrick Warburton, Oliver Hudson, Megyn Price, Bianca Kajlich 08:30 am Rules Of Engagement (Rpt) CC PG 3rd Wheel Sexual References WS Jennifer is convinced that she needs to lose weight for her wedding dress, meanwhile Audrey puts Jeff in an awkward situation when she lies to her unattractive friend. -

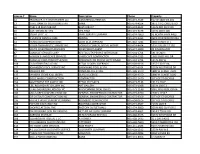

License # Name Description Phone Property 12

License # Name Description Phone Property 12 TRAVELLER, K H INVESTMENTS LLC COMMERCIAL RENTALS 435-673-4523 912 W 1600 S B-201 13 STATE BANK OF SOUTHERN UTAH BANK 435-674-4164 395 E ST GEORGE BLVD 16 CARL'S JR RESTAURANT RESTAURANT 435-674-5622 136 N RED CLIFF DR 20 DAY, STEVEN M CPA CPA FIRM 435-673-9479 150 N 200 E 200 26 STONE CLIFF LC LAND SURVEY COMPANY 435-674-1600 20 NORTH MAIN #400 50 RIVERSIDE DENTAL CARE DENTAL 435-673-3363 368 E RIVERSIDE DR #2A 54 TIERRA DEVELOPMENTS INC LAND DEVELOPMENT 435-862-7241 1060 S MAIN ST 1 62 KOLOB THERAPEUTIC SERVICE INC LICENSED CLINICAL SOCIAL WORKE 435-674-4464 1031 S BLUFF ST 102 86 SOLTIS INVESTMENT ADVISORS INVESTMENT AGENT 435-674-1600 20 N MAIN #400 87 DANVILLE SERVICES CORP RES FACILITY/PEOPLE WITH DISAB 435-634-1704 191 W 200 S 90 HANSEN'S LANDSCAPE SERVICES LANDSCAPE CONTRACTOR 435-674-2325 1365 SAND HILL DR 95 DANVILLE EMPLOYMENT SERVICE PROGRAM FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABI 435-634-1704 145 N 400 W 108 GS DISTRIBUTING CO INC RETAIL FLOOR COVERINGS 435-628-0156 1357 S 320 E #A 127 JOHANSEN'S POOL SERVICE INC SWIMMING POOL & SPA 435-673-6024 928 N WESTRIDGE DR 136 MAVERIK INC CONVENIENCE STORE 435-628-3370 1880 W SUNSET BLVD 137 MAVERIK STORE #241 (BEER) CLASS A LICENSE 435-628-3370 1880 W SUNSET BLVD 164 GOLD WHEEL CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTOR 435-632-1470 CITY OF ST GEORGE 166 SOUTHWEST TILE SUPPLY INC RETAIL TILE SALES 435-673-7133 1512 S 270 E 173 LEE, ROLAND ART GALLERY INC ART GALLERY 435-673-1988 165 N 100 E 2 178 UTAH GASTROENTEROLOGY PC PHYSICIAN/MEDICAL OFFICE 435-673-1149 368 E RIVERSIDE -

Save George's Faces in Social Networks Where Contexts Collapse

Saveface: Save George’s faces in Social Networks where Contexts Collapse By Fuming Shih and Sharon Paradesi [email protected], [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1. Introduction Social networks have repeatedly perplexed Web architects with the dilemma of privacy versus publicity. Is it ever possible to protect privacy on a platform that exists and is designed to share user’s information publicly? Despite the efforts of increasing privacy controls for its users, Facebook has continuously made the headline news concerning privacy issues [7]. Seemingly, more controls to a user’s content does not afford a satisfactory solution to diminish privacy risks [8]. Studies have shown that it is unreasonable for a user to foretell all the possible consequences of information disclosure and set an ex ante rule about privacy [10]. The real challenges about privacy protection in social networks, as some researchers argue, are the dynamics of social contexts [4], and the deficiency of current architecture in utilizing contextual information [2]. Through this paper, we demonstrate a need to create a sustainable architecture to create and implement viable privacy awareness measures and practices for different actors within the social network ‘eco- system’. Also, by monitoring transfer of information and social actions within the system, the system would be able to suggest the policy decisions being made to the user. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. We explain the meaning of context within social networks, the limitations in the current social networks and finally highlight research directions that will help in implementing a sound privacy infrastructure.