To Be a Chief and to Remain a Chief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda National a Uganda National Roads Authority

Rethinking the Big Picture of UNRA’s Business ROADS AUTHORITY(UNRA) UGANDA NATIONAL JUNE 2012 2012/13 – 2016/17 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Content Page Section Content Page 11 SWOT Analysis 1 Message from the UNRA 03 21 Chairperson & Board 2 Message from the Executive 04 12 PEST Analysis Director 27 3 Background 05 13 Critical Success Factors 29 4 Introduction 08 14 Business Context 31 5 UNRA Strategy Translation 11 Process 15 Grand Strategy 36 6 UNRA Va lue Cha in 12 16 Grand Strategy Map 37 7 Mission Statement 13 17 Goals and Strategies 8 Corporate Values 14 39 18 Implementing and 9 Assumptions 15 Monitoring the Plan 51 10 Vision Statement 19 19 Programme of Key Road Development Activities 53 2 SECTION 1. Message from the Chairperson Dear Staff at UNRA, In return, the Board will expect higher It is with great privilege and honour that I write to performance and greater accountability from thank you for your participation in the defining for Management and staff. Everyone must play his the firs t time the Stra teg ic Direc tion UNRA will t ak e role in delivering on the goals set in this over the coming 5 years. On behalf of the UNRA strategic plan. The proposed performance Board of Directors, I salute you for this noble effort. measurement framework will provide a vital tool for assessing progress towards to achievement The Strategic Plan outlines a number of strategic of the set targets. options including facilitating primary growth sectors (agriculture, industry, mining and tourism), Let me take this opportunity to appeal to improving the road condition, providing safe roads everyone to support the ED in implementing this and ensuring value for money. -

Industrialisation Sub-Sector

INDUSTRIALISATION SUB-SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 APRIL 2020 MOFPED #DoingMore Industrialisation Sub-Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2019/20 A INDUSTRIALISATION SUB-SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 APRIL 2020 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... ii Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1: Background .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Sector Mandate .......................................................................................................................................................................2 1.3 Sector Objectives ...................................................................................................................................................................2 -

Mapping Regional Reconciliation in Northern Uganda

Mapping Regional Reconciliation in Northern Uganda: A Case Study of the Acholi and Lango Sub-Regions Shilpi Shabdita Okwir Isaac Odiya Mapping Regional Reconciliation in Northern Uganda © 2015, Justice and Reconciliation Project, Gulu, Uganda All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: Justice and Reconciliation Project Plot 50 Lower Churchill Drive, Laroo Division P.O. Box 1216 Gulu, Uganda, East Africa [email protected] Layout by Lindsay McClain Opiyo Front cover photo by Shilpi Shabdita Printed by the Justice and Reconciliation Project, Gulu, Uganda This publication was supported by a grant from USAID SAFE Program. However, the opinions and viewpoints in the report is not that of USAID SAFE Program. ii Justice and Reconciliation Project Acknowledgements This report was made possible with a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity and Peace (SAFE) Program for the initiation of the year-long project titled, “Across Ethnic Boundaries: Promoting Regional Reconciliation in Acholi and Lango Sub-Regions,” for which the Justice and Reconciliation Project (JRP) gratefully acknowledges their support. We are deeply indebted to Boniface Ojok, Head of Office at JRP, for his inspirational leadership and sustained guidance in this initiative. Special thanks to the enumerators Abalo Joyce, Acan Grace, Nyeko Simon, Ojimo Tycoon, Akello Paska Oryema and Adur Patritia Julu for working tirelessly to administer the opinion survey and to collect data, which has formed the blueprint of this report. -

The Project for Community Development for Promoting Return and Resettlement of Idp in Northern Uganda

OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER AMURU DISTRICT/ NWOYA DISTRICT THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE PROJECT FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FOR PROMOTING RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT OF IDP IN NORTHERN UGANDA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NTC INTERNATINAL CO., LTD. EID JR 11-048 Uganda Amuru Location Map of Amuru and Nwoya Districts Location Map of the Target Sites PHOTOs Urgent Pilot Project Amuru District: Multipurpose Hall Outside View Inside View Handing over Ceremony (December 21 2010) Amuru District: Water Supply System Installation of Solar Panel Water Storage facility (For solar powered submersible pump) (30,000lt water tank) i Amuru District: Staff house Staff House Local Dance Team at Handing over Ceremony (1 Block has 2 units) (October 27 2010) Pabbo Sub County: Public Hall Outside view of public hall Handing over Ceremony (December 14 2010) ii Pab Sub County: Staff house Staff House Outside View of Staff House (1 Block has 2 units) (4 Block) Pab Sub County: Water Supply System Installed Solar Panel and Pump House Training on the operation of the system Water Storage Facility Public Tap Stand (40,000lt water tank) (5 stands; 4tap per stand) iii Pilot Project Pilot Project in Pabbo Sub-County Type A model: Improvement of Technical School Project Joint inspection with District Engineer & Outside view of the Workshop District Education Officer Type B Model: Pukwany Village Improvement of Access Road Project River Crossing After the Project Before the Project (No crossing facilities) (Pipe Culver) Road Rehabilitation Before -

Atiak Massacre

THE JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION PROJECT: FIELD NOTES Liu Institute for Global Issues and the Gulu District NGO Forum Field Notes, No. 4, April 2007 Remembering the Atiak Massacre April 20th 1995 All of us live as if our bodies do not have Twelve years later, the wounds of the souls. If you think of the massacre and the massacre have far from healed. As the children we have been left with, you feel so survivor’s testimony at the beginning of this bad.1 report puts it, “all of us live as if our bodies do not have souls.” Despite the massacre INTRODUCTION being one of the largest and by reputation most notorious in the twenty-one year On April 20th 1995, the Lord’s Resistance history of the conflict, no official record, Army (LRA) entered the trading centre of investigation or acknowledgement of events Atiak and after an intense offensive, exists. No excavation of the mass grave has defeated the Ugandan army stationed there. been conducted and therefore the exact Hundreds of men, women, students and number of persons killed is not known. young children were then rounded up by the Survivors literally live with the remains of LRA and marched a short distance into the bullet fragments inside them. Although the bush until they reached a river. There, they massacre site is only a few kilometres from were separated into two groups according to the trading centre, a proper burial of those their sex and age. After being lectured for slaughtered 12 years ago is not complete: as their alleged collaboration with the one survivor reminds us, “the bodies of Government, the LRA commander in charge some people were never brought back home, ordered his soldiers to open fire three times because there were no relatives to carry on a group of about 300 civilian men and them home.” boys as women and young children witnessed the horror. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

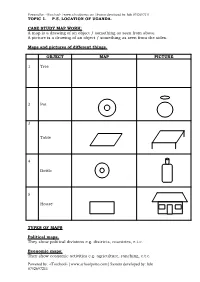

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

The Refugee Voice

The Refugee VoiceJesuit Refugee Service/USA August 2010 — Vol 4, Issue 3 Peace through education in Southern Sudan alking amidst the lush tall grasses of Eastern Equatoria State in Southern Sudan and looking at the peaceful verdant hills dotted with trees, it is hard Wto imagine the chaos and carnage that raged throughout the area from 1983 until 2005. After a generation of civil war, the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) on January 9, 2005 ended armed hostilities between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the Government of Sudan. The agreement created the semi-autonomous Government of South Sudan (GoSS) controlled by the SPLM, and provided for a six-year interim period leading up to a referendum on independence that is due to take place on January 9, 2011. Challenges to Peace Since the signing of the CPA, some 320,000 refugees and 50,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) have returned home to Southern Sudan. Re-establishing their communities has been no easy task. There is little modern infrastructure in the country, as development was stalled by more than twenty years of war. Returning refugees have had to relearn the skills of subsistence farming, growing cassava, maize and beans in the rich red soil, often competing for land and water with those people who stayed behind during the conflict. Gradually, peace has made possible the beginnings continued on page 2 A Note from the NAtioNAl Director Dear Friends of JRS/USA: In the early 1990s, JRS started providing basic education to Southern Sudanese refugees in camps in Uganda and Kenya. -

Atiak Town Board Proposed Physical Development Plan to Nimule Border Tiak T.I a Rls a Gi Onic St.M

400500.000000 40140010.0000000 401500.000000 40240020.0000000 402500.000000 40340030.0000000 403500.000000 4040040.0000000 404500.000000 ATIAK TOWN BOARD ATIAK TOWN BOARD PROPOSED PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN TO NIMULE BORDER TIAK T.I A RLS A GI ONIC ST.M K IA 2012-2022 T A II .C H L A N IO T A N Legend R E T IN LOCAL CENTER R E H T O PLANNING AREA BOUNDARY M LOCAL DISTRIBUTOR 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . LDR . 0 0 0 0 SECONDARY ROAD 3 3 0 0 6 6 0 0 3 3 2 3 3 6 6 3 3 LDR CONTOURS SECONDARY RING ROAD MDR PROPOSED LAND USES PRIMARY ROAD U LC R B A N STREAM A HDR G HIGH DENSITY RESIDENTIAL R IC MDR U L T U MDR R MEDIUM DENSITY RESIDENTIAL E LDR LOW DENSITY RESIDENTIAL 0 0 0 0 0 URBAN AGRICULTURE 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 HDR MDR 0 5 5 2 2 INSTITUTIONAL 6 6 3 3 LAND FILL P.TI PROPOSED TERTIARY INSTITUTION P.SS PROPOSED SECONDARY SCHOOL P.PS PROPOSED PRIMARY SCHOOL L O C CIVIC A L C E N T E R PB POLICE BARRACKS 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 COM 0 2 2 0 0 6 6 0 0 3 3 2 2 PRISON LAND 6 6 3 3 INDUSTRIAL WPS WATER PUMPING STATION URBAN AGRICULTURE MDR COM COMMERCIAL WATER RESERVOIR LDR HOTEL ZONE WR MDR MARKET INDUSTRIAL S AL S. -

Uganda Is Now Africa's Biggest Refugees Host

// The Five Industries Set To // Usher Komugisha: From “Kwepena // Kagame’s African // Kemiyondo Coutinho: How Transform Uganda’s Economy girl” to Globe trotting sports pundit Union Mission She Found Kemi-stry with the Arts! WWW.LEOAFRICAINSTITUTE.ORG ISSUE 2 . OCTOBER 2017 INVESTMENT IN YOUTH KEY TO INNOVATION IN AFRICA INTRODUCING the ‘LITTLE RED CURIOUS’ AND THE ART OF CUSTOM-MADE SUITS future IN UGANDA ///INSIDE UGANDA’S PROGRESSIVE REFUGEES POLICY Introducing the YELP Class of 2017 In January, the Institute welcomed the inaugural The 2017 class includes some of the most class of the Young and Emerging Leaders Project outstanding young and emerging leaders from (YELP). The 2017 class has 20 fellows drawn from Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda working in civil Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda who will undertake society, the public sector and private enterprise. three seminars on defining values in leadership- shaping personal leadership, defining and We anticipate in time to build a critical mass of achieving success, and the graduation seminar individuals committed to personal development, on cultivating servant leadership values - living advancement of career, and shaping a personal legacies. progressive future for East Africa and Africa at large. The fellowship represents our signature leadership development project shaped along In the meantime, join us in welcoming the pioneer the principles of servant leadership. 2017 class who will be graduating early 2018 and will be inducted into the Institute’s network of outstanding individuals in East Africa. -

Linking the Origin, Ethnic Identity and Settlement of the Nubis in Uganda

Vol. 11(3), pp. 26-34, March 2019 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC2019.0428 Article Number: 3410C7860468 ISSN 2141-6672 Copyright ©2019 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article African Journal of History and Culture http://www.academicjournals.org/AJHC Full Length Research Paper ‘‘We Did Not Come as Mercenaries…!’: Linking the Origin, Ethnic Identity and Settlement of the Nubis in Uganda Abudul Mahajubu*, Balunywa M. and Musisi F. Faculty of Education, Department of Oral Documentation and Research, Muteesa I Royal University, Kampala, Uganda. Received 30 January, 2019; Accepted 25 February, 2019 Focusing on the period 1894 to 1995 and drawing on both written and oral sources, this article explores the origin, ethnic identity and settlement of the Nubians since their advent in Uganda. Ugandan Nubians abandoned some aspects of their former African traditional customs and adopted new ones borrowed from the Arabic culture, constituting a unique and distinct ethnic group. Using a historical research design and adopting a qualitative approach, the article articulates the fluidity and formation of the Nubian ethnic identity on one hand, and the strategies that the Nubians have used to define and sustain themselves as a distinct ethnic group in Uganda. The article therefore suggests that the question of the Nubian identity in Uganda, through tracing their origin, ethnic identity and settlement since their advent, goes beyond the primordial understanding of ethnicity that tags ancestral location or settlement pattern, language, family history to a particular group claiming itself ethnic. Key words: Ethnicity, Nubians, Nubis, origin, identity, settlement. INTRODUCTION Who are the Uganda Nubians? What historical and the Uganda Nubis as they are conventionally known connection do they have with the Nubians of Southern as the Nubis. -

In Uganda: Making Wcd Recommendations a Reality in Uganda

A REPORT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP ON LAUNCHING OF THE WORLD COMMISSION ON DAMS (WCD) IN UGANDA: MAKING WCD RECOMMENDATIONS A REALITY IN UGANDA. ORGANIZED BY THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSIONAL ENVIRONMENTALISTS (NAPE) 19, OCTOBER 2004 HOTEL AFRICANA KAMPALA, UGANDA. Funded By Ford Foundation CONTENTS ACRONYMS………………………………………………………………………….. 3 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………….. 4 1.0. WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS…………………………………………………... 5 1.1. THE OPENING REMARKS………………………………………………………5 1.2. KEYNOTE ADDRESS BY THE WORLD BANK REPRESENTATIVE ……….6 1.3 THE OFFICIAL OPENING. ………………………………………………………7 2.0. HIGHLIGHTS OF THE PRESENTATIONS……………………………………..9 2.1. THE GENESIS OF WCD..………………………………………………………...9 2.2. THE WCD AND DAMS DEVELOPKMENT PROJECT (DDP)………………...11 2.3. IMPLICATIONS OF WCD RECOMMENDATIONS ON DEVELOPING UGANDAS WATER AND ENERGY RESOURCES…………………………....13 2.4. MAKING THE WCD RECOMMENDATIONS A REALITY IN UGANDA…...15 2.5. SHARING THE SOUTH AFRICAN EXPERIENCE…………………………….17 3.0. DISCUSSIONS……………………………………………………………………19 4.0. WAY FORWARD…………………………………………………………………21 5.0. WAY FORWARD AND CLOSURE……………………………………………...23 APPENDICES I. WORKSHOP PROGRAMME...…………..…………………………………….…………….24 II. MINISTERS’ OPENING SPEECH………………………..…………………..26 III. THE GENESIS OF WCD………………………………………...……………29 IV. THE IMPLICATIONS OF WCD RECOMMENDATION ON DEVELOPING UGANDA’S WATER AND ENERGY RESOURCES….….............................32. V. MAKING WCD RECOMMENDATIONS A REALITY IN UGANDA……...35 VI. SHARING SOUTH AFRICAS’ EXPERIENCE………………………………38 VII. CLOSING