A Survey of Corporate Governance in Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privatization in Russia: Catalyst for the Elite

PRIVATIZATION IN RUSSIA: CATALYST FOR THE ELITE VIRGINIE COULLOUDON During the fall of 1997, the Russian press exposed a corruption scandal in- volving First Deputy Prime Minister Anatoli Chubais, and several other high- ranking officials of the Russian government.' In a familiar scenario, news organizations run by several bankers involved in the privatization process published compromising material that prompted the dismissal of the politi- 2 cians on bribery charges. The main significance of the so-called "Chubais affair" is not that it pro- vides further evidence of corruption in Russia. Rather, it underscores the im- portance of the scandal's timing in light of the prevailing economic environment and privatization policy. It shows how deliberate this political campaign was in removing a rival on the eve of the privatization of Rosneft, Russia's only remaining state-owned oil and gas company. The history of privatization in Russia is riddled with scandals, revealing the critical nature of the struggle for state funding in Russia today. At stake is influence over defining the rules of the political game. The aim of this article is to demonstrate how privatization in Russia gave birth to an oligarchic re- gime and how, paradoxically, it would eventually destroy that very oligar- chy. This article intends to study how privatization influenced the creation of the present elite structure and how it may further transform Russian decision making in the foreseeable future. Privatization is generally seen as a prerequisite to a market economy, which in turn is considered a sine qua non to establishing a democratic regime. But some Russian analysts and political leaders disagree with this approach. -

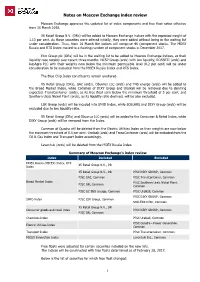

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

Telenor Mobile Communications AS V. Storm LLC

07-4974-cv(L); 08-6184-cv(CON); 08-6188-cv(CON) Telenor Mobile Communications AS v. Storm LLC Lynch, J. S.D.N.Y. 07-cv-6929 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT SUMMARY ORDER RULINGS BY SUMMARY ORDER DO NOT HAVE PRECEDENTIAL EFFECT. CITATION TO SUMMARY ORDERS FILED AFTER JANUARY 1, 2007, IS PERMITTED AND IS GOVERNED BY THIS COURT’S LOCAL RULE 32.1 AND FEDERAL RULE OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE 32.1. IN A BRIEF OR OTHER PAPER IN WHICH A LITIGANT CITES A SUMMARY ORDER, IN EACH PARAGRAPH IN WHICH A CITATION APPEARS, AT LEAST ONE CITATION MUST EITHER BE TO THE FEDERAL APPENDIX OR BE ACCOMPANIED BY THE NOTATION: (SUMMARY ORDER). A PARTY CITING A SUMMARY ORDER MUST SERVE A COPY OF THAT SUMMARY ORDER TOGETHER WITH THE PAPER IN WHICH THE SUMMARY ORDER IS CITED ON ANY PARTY NOT REPRESENTED BY COUNSEL UNLESS THE SUMMARY ORDER IS AVAILABLE IN AN ELECTRONIC DATABASE WHICH IS PUBLICLY ACCESSIBLE WITHOUT PAYMENT OF FEE (SUCH AS THE DATABASE AVAILABLE AT HTTP://WWW.CA2.USCOURTS.GOV/). IF NO COPY IS SERVED BY REASON OF THE AVAILABILITY OF THE ORDER ON SUCH A DATABASE, THE CITATION MUST INCLUDE REFERENCE TO THAT DATABASE AND THE DOCKET NUMBER OF THE CASE IN WHICH THE ORDER WAS ENTERED. 1 At a stated term of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, held at the 2 Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse, 500 Pearl Street, in the City of New York, on 3 the 8th day of October, two thousand nine, 4 5 PRESENT: 6 ROBERT D. -

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals After the Crisis: Results of 2011

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals after the Crisis: Results of 2011 Report dated April 16, 2013 Moscow and New York, April 16, 2013 The Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, and the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment (VCC), a joint center of Columbia Law School and the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York, are releasing the results of their third survey of Russian multinationals today.1 The survey, conducted from November 2012 to February 2013, is part of a long-term study of the global expansion of emerging market non-financial multinational enterprises (MNEs).2 The present report covers the period 2009-2011. Highlights Russia is one of the leading emerging markets in terms of outward foreign direct investments (FDI). Such a position is supported not by several multinational giants but by dozens of Russian MNEs in various industries. Foreign assets of the top 20 Russian non-financial MNEs grew every year covered by this report and reached US$ 111 billion at the end of 2011 (Table 1). Large Russian exporters usually use FDI in support of their foreign activities. As a result, oil and gas and steel companies with considerable exports are among the leading Russian MNEs. However, representatives of other industries also have significant foreign assets. Many companies remained “regional” MNEs. As a result, more than 66% of the ranked companies’ foreign assets were in Europe and Central Asia, with 28% in former republics of the Soviet Union (Annex table 2). Due to the popularity of off-shore jurisdictions to Russian MNEs, some Caribbean islands and Cyprus attracted many Russian subsidiaries with low levels of foreign assets. -

Press Release (PDF)

MECHEL REPORTS THE FY2020 FINANCIAL RESULTS Consolidated revenue – 265.5 bln rubles (-8% compared to FY 2019) EBITDA* – 41.1 bln rubles (-23% compared to FY 2019) Profit attributable to equity shareholders of Mechel PAO – 808 mln rubles Moscow, Russia – March 11, 2021 – Mechel PAO (MOEX: MTLR, NYSE: MTL), a leading Russian mining and steel group, announces financial results for the FY 2020. Mechel PAO’s Chief Executive Officer Oleg Korzhov commented: “The Group’s consolidated revenue in 2020 totaled 265.5 billion rubles, which is 8% less compared to 2019. EBITDA amounted to 41.1 billion rubles, which is 23% less year-on-year. “The mining division accounted for about 60% of the decrease in revenue. This was due to a significant decrease in coal prices year-on-year. In conditions of coronavirus limitations, many steelmakers around the world cut down on production, which could not fail to affect the demand for metallurgical coals and their price accordingly. By the year’s end the market demonstrated signs of a recovery, but due to China’s restrictions on Australian coal imports, coal prices outside on China remained low under this pressure. High prices in China have supported our mining division’s revenue to a certain extent. In 4Q2020 we increased shipments to China as best we could considering our long-term contractual obligations to partners from other countries. These circumstances became in many ways the reason for a decrease in our consolidated EBITDA. In Mechel’s other divisions EBITDA dynamics were positive year-on-year. “The decrease in the steel division’s revenue was also due to the coronavirus pandemic. -

Russian Games Market Report.Pdf

Foreword Following Newzoo’s free 42-page report on China and its games market, this report focuses on Russia. This report aims to provide understanding of the Russian market by putting it in a broader perspective. Russia is a dynamic and rapidly growing games We hope this helps to familiarize our clients and friends market, currently number 12 in the world in terms of around the globe with the intricacies of the Russian revenues generated. It is quickly becoming one of market. the most important players in the industry and its complexity warrants further attention and This report begins with some basic information on examination. The Russian market differs from its demographics, politics and cultural context, as well as European counterparts in many ways and this can be brief descriptions of the media, entertainment, telecoms traced to cultural and economic traditions, which in and internet sectors. It also contains short profiles of the some cases are comparable to their Asian key local players in these sectors, including the leading neighbours. local app stores, Search Engines and Social Networks. Russia has been a part of the Newzoo portfolio since In the second part of the report we move onto describe 2011, allowing us to witness first-hand the the games market in more detail, incorporating data unprecedented growth and potential within this from our own primary consumer research findings as market. We have accumulated a vast array of insights well as data from third party sources. on both the Russian consumers and the companies that are feeding this growth, allowing us to assist our clients with access to, and interpretation of, data on We also provide brief profiles of the top games in Russia, the Russia games market. -

Alfa Annual Report

ALFA GROUP CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND REPORT OF THE AUDITORS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2001 STATEMENT OF MANAGEMENT’S RESPONSIBILITIES TO THE SHAREHOLDERS OF ALFA GROUP . International convention requires that Management prepare consolidated financial statements which give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of Alfa Group (“the Group”) at the end of each financial period and of the results, cash flows and changes in shareholders’ equity for each period. Management are responsible for ensuring that the Group keeps accounting records which disclose, with reasonable accuracy, the financial position of each entity and which enable it to ensure that the consoli- dated financial statements comply with International Accounting Standards and that their statutory accounting reports comply with the applicable country’s laws and regulations. Furthermore, appropriate adjustments were made to such statutory accounts to present the accompanying consolidated financial statements in accordance with International Accounting Standards. Management also have a general responsibility for taking such steps as are reasonably possible to safeguard the assets of the Group and to prevent and detect fraud and other irregularities. Management considers that, in preparing the consolidated financial statements set out on pages to , the Group has used appropriate and consistently applied accounting policies, which are supported by reasonable and prudent judgments and estimates and that appropriate International Accounting Standards have been followed. For and on behalf of Management Nigel J. Robinson October ZAO PricewaterhouseCoopers Audit Kosmodamianskaya Nab. 52, Bld. 5 115054 Moscow Russia Telephone +7 (095) 967 6000 Facsimile +7 (095) 967 6001 REPORT OF THE AUDITORS TO THE SHAREHOLDERS OF ALFA GROUP . -

Consolidated Accounting Reports with Independent Auditor's

PJSC GAZPROM Consolidated Accounting Reports with Independent Auditor’s Report 31 December 2020 Moscow | 2021 Contents Independent Auditor’s Report................................................................................................................... 3 Consolidated Balance Sheet ...................................................................................................................... 9 Consolidated Statement of Financial Results .......................................................................................... 11 Consolidated Statement of Changes in the Shareholders’ Equity ........................................................... 12 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows .................................................................................................. 13 Notes to the Consolidated Accounting Reports: 1. General Information ....................................................................................................................... 14 2. Significant Accounting Policies and Basis of Presentation in the Consolidated Accounting Reports ......................................................................................................................................... 14 3. Changes in the Accounting Policies and Comparative Information for Previous Reporting Periods .......................................................................................................................................... 20 4. Segment Information ..................................................................................................................... -

Deal Drivers Russia

February 2010 Deal Drivers Russia A survey and review of Russian corporate finance activity Contents Introduction 1 01 M&A Review 2 Overall deal trends 3 Domestic M&A trends 6 Cross-border M&A trends 8 Private equity 11 Acquisition finance 13 Valuations 14 02 Industries 15 Automotive 16 Energy 18 Financial Services 20 Consumer & Retail 22 Industrial Markets 24 Life Sciences 26 Mining 28 Technology, Media & Telecommunications 30 03 Survey Analysis 32 Introduction Prediction may be fast going out of fashion. At the end of 2008, CMS commissioned mergermarket to interview 100 Russian M&A and corporate decision makers to find out what they thought about the situation at the time and what their views on the future were. Falling commodity prices were viewed as the biggest threat, the Financial Services sector was expected to deliver the greatest growth for M&A activity and the bulk of inward investment was expected from Asia. The research revealed that two thirds of the respondents expected the overall level of M&A activity to increase over the course of 2009, with only one third predicting a fall. That third of respondents was right and, in general, the majority got it wrong or very wrong. The survey did get some things right – the predominance of Who knows? What’s the point? We consider the point to be the domestic players, the increase of non-money deals, the in the detail. Our survey looks at the market in 2009 sector number of transactions against a restructuring background, by sector – what was ‘in’ and what was ‘out’. -

CONGRESSIONAL PROGRAM U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era

CONGRESSIONAL PROGRAM U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era May 29 – June 3, 2018 Helsinki, Finland and Tallinn, Estonia Copyright @ 2018 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute 2300 N Street Northwest Washington, DC 20037 Published in the United States of America in 2018 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era May 29 – June 3, 2018 The Aspen Institute Congressional Program Table of Contents Rapporteur’s Summary Matthew Rojansky ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Russia 2018: Postponing the Start of the Post-Putin Era .............................................................................. 9 John Beyrle U.S.-Russian Relations: The Price of Cold War ........................................................................................ 15 Robert Legvold Managing the U.S.-Russian Confrontation Requires Realism .................................................................... 21 Dmitri Trenin Apple of Discord or a Key to Big Deal: Ukraine in U.S.-Russia Relations ................................................ 25 Vasyl Filipchuk What Does Russia Want? ............................................................................................................................ 39 Kadri Liik Russia and the West: Narratives and Prospects ......................................................................................... -

Transparency and Disclosure by Russian State-Owned Enterprises

Transparency And Disclosure By Russian State-Owned Enterprises Standard & Poor’s Governance Services Prepared for the Roundtable on Corporate Governance organized by the OECD in Moscow on June 3, 2005 Julia Kochetygova Nick Popivshchy Oleg Shvyrkov Vladimir Todres Christine Liadskaya June 2005 Transparency & Disclosure by Russian State-Owned Enterprises Transparency and Disclosure by Russian State-Owned Enterprises Executive Summary This survey of transparency and disclosure (T&D) by Russian state-owned companies by Standard & Poor’s Governance Services was prepared at the request of the OECD Roundtable on Corporate Governance. According to the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of SOEs, “the state should act as an informed and active owner and establish a clear and consistent ownership policy, ensuring that the governance of state-owned enterprises is carried out in a transparent and accountable manner” (Chapter III). Further, “large or listed SOEs should disclose financial and non financial information according to international best practices” (Chapter V). In stark contrast with these principles, the study revealed consistent differences in disclosure standards between the state-controlled and similarly sized public Russian companies. This is in line with the notion that transparency of state-controlled enterprises is hampered by the tendency of the Russian government and individual officials to use their influence on such companies to promote political or individual goals that often diverge from commercial motives and investor interests. High standards of transparency and disclosure, on the other hand, are a cornerstone in the foundation of good governance. They provide legitimate stakeholders--whether creditors, minority shareholders, taxpayers, or the general public--with the information they need to be able to begin to hold government decision-makers accountable for their actions. -

Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Is the Largest Region in the Russian Federation and One of the Richest in Natural Resources

Investor's Guide to the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is the largest region in the Russian Federation and one of the richest in natural resources. Needless to say, the stable and dynamic development of Yakutia is of key importance to both the Far Eastern Federal District and all of Russia…” President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin “One of the fundamental priorities of the Government of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is to develop comfortable conditions for business and investment activities to ensure dynamic economic growth” Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Egor Borisov 2 Contents Welcome from Egor Borisov, Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 5 Overview of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 6 Interesting facts about the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 7 Strategic priorities of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) investment policy 8 Seven reasons to start a business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 10 1. Rich reserves of natural resources 10 2. Significant business development potential for the extraction and processing of mineral and fossil resources 12 3. Unique geographical location 15 4. Stable credit rating 16 5. Convenient conditions for investment activity 18 6. Developed infrastructure for the support of small and medium-sized enterprises 19 7. High level of social and economic development 20 Investment infrastructure 22 Interaction with large businesses 24 Interaction with small and medium-sized enterprises 25 Other organisations and institutions 26 Practical information on doing business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 27 Public-Private Partnership 29 Information for small and medium-sized enterprises 31 Appendix 1.