Ambiances , Varia 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study—How Could We Optimize the Energy-Efficient Design for an Extra-Large Railway Station with a Comprehensive Simulation?

Proceedings of Building Simulation 2011: 12th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association, Sydney, 14-16 November. CASE STUDY—HOW COULD WE OPTIMIZE THE ENERGY-EFFICIENT DESIGN FOR AN EXTRA-LARGE RAILWAY STATION WITH A COMPREHENSIVE SIMULATION? Jiagen Liu1, Borong Lin1, Yufeng Zhang2, Qunfei Zhu2, Yinxin Zhu1 1Tsinghua University, People’s Republic of China 2Beijing Institute of Architecture Design, People’s Republic of China large building which contains three floors: the ground ABSTRACT floor is for arrivals, the second floor is for departures, As a famous large-scale transportation hub in China, and the third floor consists of waiting areas and the Nanjing South Railway Station (NSRS) is a huge shops. 2 building of 380,000 m and 50 meters high, with In order to meet both functional demands and complex vertical route organization and aesthetic requirements, modern station buildings are comprehensive function zones. Because of its large usually designed with high and large spaces with few façade, skylight, and huge air infiltration, the NSRS physical partitions between different areas. In has encountered many difficulties in terms of HVAC addition, in order to guarantee adequate illumination (heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning) design, and visibility, vitreous barriers and skylights are especially in calculating the most accurate heating usually employed. Another characteristic of these and cooling loads during air infiltration. In order to stations is that they serve high-density crowds that address these issues, DeST (Designer’s Simulation fluctuate significantly. Due to the enormous number Toolkit), a building energy simulation tool developed of people who use these stations, the entry and exit by Tsinghua University, was combined with other doors are always kept open, leading to a huge amount tools to simulate the NSRS’s HVAC load for an of air infiltration that greatly increases the air entire year. -

Evaluation on Transfer Reliability of Wuhan Comprehensive Transport Hub Based on Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Hao Zhang1,A

3rd International Conference on Mechatronics, Robotics and Automation (ICMRA 2015) Evaluation on Transfer Reliability of Wuhan Comprehensive Transport Hub Based on Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Hao Zhang1,a *, Xifu Wang2,b 1School of Traffic and Transportation, Beijing Jiaotong University, 100044, China 2School of Traffic and Transportation, Xifu Wang, Beijing Jiaotong University,100044, China [email protected], [email protected] Key Words: Comprehensive transport hub; Reliability Evaluation; Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation ABSTRACT:Urban Comprehensive transport hub transfer system is an important part of urban public transport network. It's functionality and high level of service is not only the needs of urban modernization, but also one of the important means to attract travelers to use public transportation to ease road congestion. The evaluation of traffic transfer system will help city managers recognize the weaknesses in city traffic and make the appropriate improvements. In this paper, we mainly discussed the urban public transportation transfer, defined the definition of reliability, and analyzed composition and the factors influence its reliability. Before analyze the public transportation transfer in Wuhan city, it's important to statistics which Urban transport hubs are involved. After that, we should build an evaluation system. Then, according to the evaluation system, we collected the relevant data and analyzed them. Finally ,through Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation, we will get the evaluation result. Introduction In the city that public transport is the main mode of transportation, comprehensive transport hub is an important node of public transportation network. It provides the transfer and combinations of traveling ways, distribution travelers. The main function of comprehensive transport hub including the following two aspects[1]. -

High Speed Rail: Wuhan Urban Garden 5-Day Trip

High Speed Rail: Wuhan Urban Garden 5-Day Trip Day 1 Itinerary Suggested Transportation Hong Kong → Wuhan High Speed Rail [Hong Kong West Kowloon Station → Wuhan Railway Station] To hotel: Recommend to stay in a hotel by the river in Wuchang District. Metro: From Wuhan Railway Hotel for reference: Station, take Metro Line 4 The Westin Wuhan Wuchang Hotel towards Huangjinkou. Address: 96 Linjiang Boulevard, Wuchang District, Wuhan Change to Line 2 at Hongshan Square Station towards Tianhe International Airport. Get off at Jiyuqiao Station and walk for about 7 minutes. (Total travel time about 46 minutes) Taxi: About 35 minutes. Enjoy lunch near the hotel On foot: Walk for about 5 minutes Restaurant for reference: Zhen Bafang Hot Pot from the hotel. Address: No. 43 & 44, Building 12-13, Qianjin Road, Wanda Plaza, Jiyu Bridge, Wuchang District, Wuhan Stand the Test of Time: Yellow Crane Tower Bus: Walk for about 4 minutes from the restaurant to Jiyuqiao Metro Station. Take bus 804 towards Nanhu Road Jiangnan Village. Get off at Yue Ma Chang Station and walk for about 6 minutes. (Total travel time about 37 minutes) Taxi: About 15 minutes. Known as “The No. 1 Tower in the World”, the Yellow Crane Tower is a landmark for Wuhan City and Hubei Province and a must-see attraction. The tower was built in the Three Kingdoms era and was named after its erection on Huangjiji, a submerged rock. Well-known ancient characters such as Li Bai, Bai Juyi, Lu You and Yue Fei had all referenced the tower in their poetry works. -

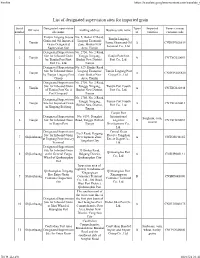

List of Designated Supervision Sites for Imported Grain

Firefox https://translate.googleusercontent.com/translate_f List of designated supervision sites for imported grain Serial Designated supervision Types Imported Venue (venue) Off zone mailing address Business unit name number site name of varieties customs code Tianjin Lingang Jiayue No. 5, Bohai 37 Road, Tianjin Lingang Grain and Oil Imported Lingang Economic 1 Tianjin Jiayue Grain and Oil A CNDGN02S619 Grain Designated Zone, Binhai New Terminal Co., Ltd. Supervision Site Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port First 2 Tianjin A CNTXG020051 by Tianjin Port First Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Co., Ltd. Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 529, Hunhe Road, Site for Inbound Grain Lingang Economic Tianjin Lingang Port 3 Tianjin A CNDGN02S620 by Tianjin Lingang Port Zone, Binhai New Group Co., Ltd. Group Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 4 Tianjin A CNTXG020448 of Tianjin Port No. 4 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Company Tianjin No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Designated Supervision Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 5 Tianjin Site for Imported Grain A CNTXG020413 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. in Xingang Beijiang Tianjin Tianjin Port Designated Supervision No. 6199, Donghai International Sorghum, corn, 6 Tianjin Site for Inbound Grain Road, Tanggu District, Logistics B CNTXG020051 sesame in Tianjin Port Tianjin Development Co., Ltd. Designated Supervision Central Grain No.9 Road, Haigang Site for Inbound Grain Reserve Tangshan 7 Shijiazhuang Development Zone, A CNTGS040165 at Jingtang Port Grocery Direct Depot Co., Tangshan City Terminal Ltd. -

Circuity Analyses of HSR Network and High-Speed Train Paths in China

RESEARCH ARTICLE Circuity analyses of HSR network and high- speed train paths in China Xinlei Hu1, Shuo Zhao1, Feng Shi1*, Jie Huang2, Xinghua Shan3 1 School of Traffic and Transportation Engineering, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China, 2 Key Laboratory of Regional Sustainable Development Modeling, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 3 Institute of Computing Technologies, China Academy of Railway Sciences, Beijing, China * [email protected] Abstract a1111111111 Circuity, defined as the ratio of the shortest network distance to the Euclidean distance a1111111111 between one origin±destination (O-D) pair, can be adopted as a helpful evaluation method a1111111111 a1111111111 of indirect degrees of train paths. In this paper, the maximum circuity of the paths of oper- a1111111111 ated trains is set to be the threshold value of the circuity of high-speed train paths. For the shortest paths of any node pairs, if their circuity is not higher than the threshold value, the paths can be regarded as the reasonable paths. With the consideration of a certain relative or absolute error, we cluster the reasonable paths on the basis of their inclusion relationship OPEN ACCESS and the center path of each class represents a passenger transit corridor. We take the high- speed rail (HSR) network in China at the end of 2014 as an example, and obtain 51 passen- Citation: Hu X, Zhao S, Shi F, Huang J, Shan X (2017) Circuity analyses of HSR network and high- ger transit corridors, which are alternative sets of train paths. Furthermore, we analyze the speed train paths in China. -

RCI Needs Assessment, Development Strategy, and Implementation Action Plan for Liaoning Province

ADB Project Document TA–1234: Strategy for Liaoning North Yellow Sea Regional Cooperation and Development RCI Needs Assessment, Development Strategy, and Implementation Action Plan for Liaoning Province February L2MN This report was prepared by David Roland-Holst, under the direction of Ying Qian and Philip Chang. Primary contributors to the report were Jean Francois Gautrin, LI Shantong, WANG Weiguang, and YANG Song. We are grateful to Wang Jin and Zhang Bingnan for implementation support. Special thanks to Edith Joan Nacpil and Zhuang Jian, for comments and insights. Dahlia Peterson, Wang Shan, Wang Zhifeng provided indispensable research assistance. Asian Development Bank 4 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City MPP2 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org © L2MP by Asian Development Bank April L2MP ISSN L3M3-4P3U (Print), L3M3-4PXP (e-ISSN) Publication Stock No. WPSXXXXXX-X The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Note: In this publication, the symbol “$” refers to US dollars. Printed on recycled paper 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 10 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Baseline Assessment .................................................................................................. 3 A. -

METROS/U-BAHN Worldwide

METROS DER WELT/METROS OF THE WORLD STAND:31.12.2020/STATUS:31.12.2020 ّ :جمهورية مرص العرب ّية/ÄGYPTEN/EGYPT/DSCHUMHŪRIYYAT MISR AL-ʿARABIYYA :القاهرة/CAIRO/AL QAHIRAH ( حلوان)HELWAN-( المرج الجديد)LINE 1:NEW EL-MARG 25.12.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmr5zRlqvHY DAR EL-SALAM-SAAD ZAGHLOUL 11:29 (RECHTES SEITENFENSTER/RIGHT WINDOW!) Altamas Mahmud 06.11.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6xG3hZccyg EL-DEMERDASH-SADAT (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 12:29 Mahmoud Bassam ( المنيب)EL MONIB-( ش ربا)LINE 2:SHUBRA 24.11.2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UCJA6bVKQ8 GIZA-FAYSAL (LINKES SEITENFENSTER/LEFT WINDOW!) 02:05 Bassem Nagm ( عتابا)ATTABA-( عدىل منصور)LINE 3:ADLY MANSOUR 21.08.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t7m5Z9g39ro EL NOZHA-ADLY MANSOUR (FENSTERBLICKE/WINDOW VIEWS!) 03:49 Hesham Mohamed ALGERIEN/ALGERIA/AL-DSCHUMHŪRĪYA AL-DSCHAZĀ'IRĪYA AD-DĪMŪGRĀTĪYA ASCH- َ /TAGDUDA TAZZAYRIT TAMAGDAYT TAỴERFANT/ الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطيةالشعبية/SCHA'BĪYA ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵣⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ : /DZAYER TAMANEỴT/ دزاير/DZAYER/مدينة الجزائر/ALGIER/ALGIERS/MADĪNAT AL DSCHAZĀ'IR ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵏⴻⵖⵜ PLACE DE MARTYRS-( ع ني نعجة)AÏN NAÂDJA/( مركز الحراش)LINE:EL HARRACH CENTRE ( مكان دي مارت بز) 1 ARGENTINIEN/ARGENTINA/REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA: BUENOS AIRES: LINE:LINEA A:PLACA DE MAYO-SAN PEDRITO(SUBTE) 20.02.2011 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfUmJPEcBd4 PIEDRAS-PLAZA DE MAYO 02:47 Joselitonotion 13.05.2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lJAhBo6YlY RIO DE JANEIRO-PUAN 07:27 Así es BUENOS AIRES 4K 04.12.2014 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PoUNwMT2DoI -

Exploring the Hierarchical Structure of China's Railway Network from 2008 to 2017

sustainability Article Exploring the Hierarchical Structure of China’s Railway Network from 2008 to 2017 Shiwei Lu 1,2,*, Yaping Huang 1,2, Zhiyuan Zhao 3,4 and Xiping Yang 5,6 ID 1 School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] 2 Hubei Engineering and Technology Research Center of Urbanization, Wuhan 430074, China 3 National & Local Joint Engineering Research Center of Geo-spatial Information Technology, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350002, China; [email protected] 4 Key Laboratory of Spatial Data Mining & Information Sharing of MOE, Fuzhou 350002, China 5 School of Geography and Tourism, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an 710119, China; [email protected] 6 Geomatics Technology and Application key Laboratory of Qinghai Province, Xining 810001, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-27-8754-2156 Received: 19 July 2018; Accepted: 31 August 2018; Published: 5 September 2018 Abstract: The analysis of transport networks is an important component of urban and regional development and planning. Based on the four main stages of China’s railway development from 2008 to 2017, this paper analyzes the hierarchical and spatial heterogeneity distribution of train flows. We found a high degree of spatial matching with the distribution of China’s main railway corridors. Then, using a classical community detection algorithm, this paper attempts to describe the functional structure and regional effects of China’s railway network. We also explore the impacts of construction policies and changes to train operations on the spatial organizing pattern and evolution of network hierarchies. The results of this empirical study reveal a clear pattern of independent communities, which in turn indicates the existence of a hierarchical structure in China’s railway network. -

47Th ISOCARP Congress Wuhan, PR China, 24-28 October 2011

47 th ISOCARP Congress Wuhan, PR China, 24-28 October 2011 PRELIMINARY CONGRESS BROCHURE PARTNERS and SPONSORS 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Words of Welcome 6 Introduction by the General Rapporteur 12 Provisional Congress Programme 16 Congress Team and Local Organising Committee 18 Congress Venue 19 Keynote Speakers 21 Technical Seminars 22 Exhibition 23 Young Planning Professionals’ Programme 25 Registration: Congress Fees and Cancellation Procedures 28 Social Events 29 Technical Tours 29 Companions’ Tours 30 Pre-Congress Tour 32 Post Congress Tours 37 Accommodation 38 General Information, incl. visa 40 About Wuhan 41 About ISOCARP, International Society of City and Regional Planners 42 About UPSC, Urban Planning Society of China 2 WELCOME by the President of ISOCARP Ismael Fernández Mejía Dear Friends and Colleagues, Just as in our previous forty-six congresses ISOCARP has put forward a subject for analysis which, today, is at the very forefront of global, political and scientific discussions. Following the analytic process that has been the conducting thread in the last few years, ISOCARP Congresses have been looking at the sustainability problem and how it was and is still affecting the planet from many different professional perspectives. In Dalian, 2008, we looked at urban sprawl, in Porto 2009 we concentrated on Low Carbon Cities in respect of the developed world, in Nairobi 2010, the subject matter focused on sustainability in developing economies. In Wuhan 2011, the overall concept is to attempt to understand how the different alternatives and initiatives can now be blended together with careful attention being paid to all of the policies that have already been discussed in our previous Congresses. -

Emerging City Market Report - Wuhan Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Tyler Babcock Prepared By: ATO Shanghai

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 3/12/2018 GAIN Report Number: CH178043 China - Peoples Republic of Post: Shanghai ATO Emerging City Market Report - Wuhan Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Tyler Babcock Prepared By: ATO Shanghai Report Highlights: The data and analyses shown in this report are the result of a market research project conducted by Euromonitor on the behalf of the Agricultural Trade Office in Shanghai. The data and analyses in this report are not the position of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rather, the data and analyses are information collected from in-field research to give the Agricultural Trade Office in Shanghai further insight into the local market. Disclaimer: The data and analyses shown in this report are the result of a market research project conducted by Euromonitor on the behalf of the Agricultural Trade Office in Shanghai. The data and analyses in this report are not the position of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rather, the data and analyses are information collected from in-field research to give the Agricultural Trade Office in Shanghai further insight into the local market. City Profiling Study of China Wuhan City A custom report compiled by Euromonitor International for USDA FAS November 2016 Contents 0. Research Background............................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 0.1 Research Objective ......................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 0.2 Research Coverage .......................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 0.3 Research Methodology ................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 0.4 Forecast Assumptions .................................................... -

Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 1: Introduction 7

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Place-making around high-speed railway stations in China Dai, G. Publication date 2015 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dai, G. (2015). Place-making around high-speed railway stations in China. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 5 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 6 Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 1: Introduction 7 Ourdoor dancing at Wuhan Railway Station, Photo: Author, 2011 8 Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 1: Introcuction 9 Introduction Lingering under the streamlined roof of the brand-new Wuhan Railway Station, one would be amazed by its magnificent scale (114602m2) and avant-garde architectural design. It might remind passengers of some works of star architects in Europe, such as the Euralille by OMA (1994) or Liège-Guillemins Railway Station by Santiago Calatrava (2009). -

China City Profiles 2012 an Overview of 20 Retail Locations

China City Profiles 2012 An Overview of 20 Retail Locations joneslanglasalle.com.cn China Retail Profiles 2012 The China market presents a compelling opportunity for retailers. China’s retail sector has long been firmly underpinned by solid demand fundamentals–massive population, rapid urbanization and an emerging consumer class. Annual private consumption has tripled in the last decade, and China is on track to become the world’s second largest consumer market by 2015. China’s consumer class will more than double from 198 million people today to 500 million by 2022, if we define it as people earning over USD 5,000 per annum in constant 2005 dollars. It is never too late to enter the China market. China’s economic growth model is undergoing a shift from investment- led growth to consumption-led growth. It is widely recognized that government-led investment, while effective in the short term, is not the solution to long-term growth. With its massive accumulated household savings and low household debt levels, China’s domestic consumption offers immense headroom for growth. China’s leaders are acutely aware of the urgency to effect changes now and are more eager than ever before to tap its consumers for growth. Already, the government has set in motion a comprehensive range of pro-consumption policies to orchestrate a consumption boom. Broadly, the wide-ranging policies include wage increases, tax adjustments, strengthening of the social safety net, job creation, promotion of urbanization and affordable housing. While the traditional long-term demand drivers–urbanization, rising wealth and robust income growth–remain firmly intact, China’s retail story has just been given a structural boost.