Why High-Speed Railway Stations Continue China's Leapfrog Urbanization?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operator's Story Case Study: Guangzhou's Story

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Case Study: Guangzhou’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from Guangzhou Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in Guangzhou, China. These notes are based upon 3 meetings on the 11th March 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece. Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. This mini case study does not attempt to provide a comprehensive picture of Guangzhou Metropolitan Corporation (GMC), but rather focuses on specific topics of interest to The Operators’ Story project. The research team thank GMC and its staff for their kind participation in this project. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and GMC. List of interviewees Meetings include the following GMC members: Mr. -

Guangzhou South Railway Station 广州南站/ South of Shixing Avenue, Shibi Street, Fanyu District

Guangzhou South Railway Station 广州南站/ South of Shixing Avenue, Shibi Street, Fanyu District, Guangzhou 广州番禹区石壁街石兴大道南 (86-020-39267222) Quick Guide General Information Board the Train / Leave the Station Transportation Station Details Station Map Useful Sentences General Information Guangzhou South Railway Station (广州南站), also called New Guangzhou Railway Station, is located at Shibi Street, Panyu District, Guangzhou, Guangdong. It has served Guangzhou since 2010, and is 17 kilometers from the city center. It is one the four main railway stations in Guangzhou. The other three are Guangzhou Railway Station, Guangzhou North Railway Station, and Guangzhou East Railway Station. After its opening, Guangzhou South Railway Station has been gradually taking the leading role of train transport from Guangzhou Railway Station, becoming one of the six key passenger train hubs of China. Despite of its easy accessibility from every corner of the city, ticket-checking and waiting would take a long time so we strongly suggest you be at the station as least 2 hours prior to your departure time, especially if you haven’t bought tickets in advance. Board the Train / Leave the Station Boarding progress at Guangzhou South Railway Station: Square of Guangzhou South Railway Station Ticket Office (售票处) at the east and northeast corner of F1 Get to the Departure Level F1 by escalator E nter waiting section after security check Buy tickets (with your travel documents) Pick up tickets (with your travel documents and booking number) Find your own waiting line according to the LED screen or your tickets TOP Wait for check-in Have tickets checked and take your luggage Walk through the passage and find your boarding platform Board the train and find your seat Leaving Guangzhou South Railway Station: Passengers can walk through the tunnel to the exit after the trains pull off. -

Download 3.94 MB

Environmental Monitoring Report Semiannual Report (March–August 2019) Project Number: 49469-007 Loan Number: 3775 February 2021 India: Mumbai Metro Rail Systems Project Mumbai Metro Rail Line-2B Prepared by Mumbai Metropolitan Development Region, Mumbai for the Government of India and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVATION ADB - Asian Development Bank ADF - Asian Development Fund CSC - construction supervision consultant AIDS - Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome EA - execution agency EIA - environmental impact assessment EARF - environmental assessment and review framework EMP - environmental management plan EMR - environmental Monitoring Report ESMS - environmental and social management system GPR - Ground Penetrating Radar GRM - Grievance Redressal Mechanism IEE - initial environmental examination MMRDA - Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority MML - Mumbai Metro Line PAM - project administration manual SHE - Safety Health & Environment Management Plan SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km - Kilometer -

Your Paper's Title Starts Here

2019 International Conference on Computer Science, Communications and Big Data (CSCBD 2019) ISBN: 978-1-60595-626-8 Problems and Measures of Passenger Organization in Guangzhou Metro Stations Ting-yu YIN1, Lei GU1 and Zheng-yu XIE1,* 1School of Traffic and Transportation, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, 100044, China *Corresponding author Keywords: Guangzhou Metro, Passenger organization, Problems, Measures. Abstract. Along with the rapidly increasing pressure of urban transportation, China's subway operation is facing the challenge of high-density passenger flow. In order to improve the level of subway operation and ensure its safety, it is necessary to analyze and study the operation status of the metro station under the condition of high-density passenger flow, and propose the corresponding improvement scheme. Taking Guangzhou Metro as the study object, this paper discusses and analyzes the operation and management status of Guangzhou Metro Station. And combined with the risks and deficiencies in the operation and organization of Guangzhou metro, effective improvement measures are proposed in this paper. Operation Status of Guangzhou Metro The first line of Guangzhou Metro opened on June 28, 1997, and Guangzhou became the fourth city in mainland China to open and operate the subway. As of April 26, 2018, Guangzhou Metro has 13 operating routes, with 391.6 km and 207 stations in total, whose opening mileage ranks third in China and fourth in the world now. As of July 24, 2018, Guangzhou Metro Line Network had transported 1.645 billion passengers safely, with an average daily passenger volume of 802.58 million, an increase of 7.88% over the same period of 2017 (7.4393 million). -

Case Study—How Could We Optimize the Energy-Efficient Design for an Extra-Large Railway Station with a Comprehensive Simulation?

Proceedings of Building Simulation 2011: 12th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association, Sydney, 14-16 November. CASE STUDY—HOW COULD WE OPTIMIZE THE ENERGY-EFFICIENT DESIGN FOR AN EXTRA-LARGE RAILWAY STATION WITH A COMPREHENSIVE SIMULATION? Jiagen Liu1, Borong Lin1, Yufeng Zhang2, Qunfei Zhu2, Yinxin Zhu1 1Tsinghua University, People’s Republic of China 2Beijing Institute of Architecture Design, People’s Republic of China large building which contains three floors: the ground ABSTRACT floor is for arrivals, the second floor is for departures, As a famous large-scale transportation hub in China, and the third floor consists of waiting areas and the Nanjing South Railway Station (NSRS) is a huge shops. 2 building of 380,000 m and 50 meters high, with In order to meet both functional demands and complex vertical route organization and aesthetic requirements, modern station buildings are comprehensive function zones. Because of its large usually designed with high and large spaces with few façade, skylight, and huge air infiltration, the NSRS physical partitions between different areas. In has encountered many difficulties in terms of HVAC addition, in order to guarantee adequate illumination (heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning) design, and visibility, vitreous barriers and skylights are especially in calculating the most accurate heating usually employed. Another characteristic of these and cooling loads during air infiltration. In order to stations is that they serve high-density crowds that address these issues, DeST (Designer’s Simulation fluctuate significantly. Due to the enormous number Toolkit), a building energy simulation tool developed of people who use these stations, the entry and exit by Tsinghua University, was combined with other doors are always kept open, leading to a huge amount tools to simulate the NSRS’s HVAC load for an of air infiltration that greatly increases the air entire year. -

(Presentation): Improving Railway Technologies and Efficiency

RegionalConfidential EST Training CourseCustomizedat for UnitedLorem Ipsum Nations LLC University-Urban Railways Shanshan Li, Vice Country Director, ITDP China FebVersion 27, 2018 1.0 Improving Railway Technologies and Efficiency -Case of China China has been ramping up investment in inner-city mass transit project to alleviate congestion. Since the mid 2000s, the growth of rapid transit systems in Chinese cities has rapidly accelerated, with most of the world's new subway mileage in the past decade opening in China. The length of light rail and metro will be extended by 40 percent in the next two years, and Rapid Growth tripled by 2020 From 2009 to 2015, China built 87 mass transit rail lines, totaling 3100 km, in 25 cities at the cost of ¥988.6 billion. In 2017, some 43 smaller third-tier cities in China, have received approval to develop subway lines. By 2018, China will carry out 103 projects and build 2,000 km of new urban rail lines. Source: US funds Policy Support Policy 1 2 3 State Council’s 13th Five The Ministry of NRDC’s Subway Year Plan Transport’s 3-year Plan Development Plan Pilot In the plan, a transport white This plan for major The approval processes for paper titled "Development of transportation infrastructure cities to apply for building China's Transport" envisions a construction projects (2016- urban rail transit projects more sustainable transport 18) was launched in May 2016. were relaxed twice in 2013 system with priority focused The plan included a investment and in 2015, respectively. In on high-capacity public transit of 1.6 trillion yuan for urban 2016, the minimum particularly urban rail rail transit projects. -

Evaluation on Transfer Reliability of Wuhan Comprehensive Transport Hub Based on Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Hao Zhang1,A

3rd International Conference on Mechatronics, Robotics and Automation (ICMRA 2015) Evaluation on Transfer Reliability of Wuhan Comprehensive Transport Hub Based on Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Hao Zhang1,a *, Xifu Wang2,b 1School of Traffic and Transportation, Beijing Jiaotong University, 100044, China 2School of Traffic and Transportation, Xifu Wang, Beijing Jiaotong University,100044, China [email protected], [email protected] Key Words: Comprehensive transport hub; Reliability Evaluation; Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation ABSTRACT:Urban Comprehensive transport hub transfer system is an important part of urban public transport network. It's functionality and high level of service is not only the needs of urban modernization, but also one of the important means to attract travelers to use public transportation to ease road congestion. The evaluation of traffic transfer system will help city managers recognize the weaknesses in city traffic and make the appropriate improvements. In this paper, we mainly discussed the urban public transportation transfer, defined the definition of reliability, and analyzed composition and the factors influence its reliability. Before analyze the public transportation transfer in Wuhan city, it's important to statistics which Urban transport hubs are involved. After that, we should build an evaluation system. Then, according to the evaluation system, we collected the relevant data and analyzed them. Finally ,through Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation, we will get the evaluation result. Introduction In the city that public transport is the main mode of transportation, comprehensive transport hub is an important node of public transportation network. It provides the transfer and combinations of traveling ways, distribution travelers. The main function of comprehensive transport hub including the following two aspects[1]. -

5G for Trains

5G for Trains Bharat Bhatia Chair, ITU-R WP5D SWG on PPDR Chair, APT-AWG Task Group on PPDR President, ITU-APT foundation of India Head of International Spectrum, Motorola Solutions Inc. Slide 1 Operations • Train operations, monitoring and control GSM-R • Real-time telemetry • Fleet/track maintenance • Increasing track capacity • Unattended Train Operations • Mobile workforce applications • Sensors – big data analytics • Mass Rescue Operation • Supply chain Safety Customer services GSM-R • Remote diagnostics • Travel information • Remote control in case of • Advertisements emergency • Location based services • Passenger emergency • Infotainment - Multimedia communications Passenger information display • Platform-to-driver video • Personal multimedia • In-train CCTV surveillance - train-to- entertainment station/OCC video • In-train wi-fi – broadband • Security internet access • Video analytics What is GSM-R? GSM-R, Global System for Mobile Communications – Railway or GSM-Railway is an international wireless communications standard for railway communication and applications. A sub-system of European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS), it is used for communication between train and railway regulation control centres GSM-R is an adaptation of GSM to provide mission critical features for railway operation and can work at speeds up to 500 km/hour. It is based on EIRENE – MORANE specifications. (EUROPEAN INTEGRATED RAILWAY RADIO ENHANCED NETWORK and Mobile radio for Railway Networks in Europe) GSM-R Stanadardisation UIC the International -

Research Article Coordination Optimization of the First and Last Trains’ Departure Time on Urban Rail Transit Network

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Advances in Mechanical Engineering Volume 2013, Article ID 848292, 12 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/848292 Research Article Coordination Optimization of the First and Last Trains’ Departure Time on Urban Rail Transit Network Wenliang Zhou, Lianbo Deng, Meiquan Xie, and Xia Yang School of Traffic and Transportation Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410075, China Correspondence should be addressed to Meiquan Xie; [email protected] Received 17 August 2013; Revised 11 October 2013; Accepted 6 November 2013 Academic Editor: Wuhong Wang Copyright © 2013 Wenliang Zhou et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Coordinating the departure times of different line directions’ of first and the last trains contributes to passengers’ transferring. In this paper, a coordination optimization model (i.e., M1) referring to the first train’s departure time is constructed firstly to minimize passengers’ total originating waiting time and transfer waiting time for the first trains. Meanwhile, the other coordination optimization model (i.e., M2) of the last trains’ departure time is built to reduce passengers’ transfer waiting time for the last trains and inaccessible passenger volume of all origin-destination (OD) and improve passengers’ accessible reliability for the last trains. Secondly, two genetic algorithms, in which a fixed-length binary-encoding string is designed according to the time interval between the first train departure time and the earliest service time of each line direction or between the last train departure time and the latest service time of each line direction, are designed to solve M1 and M2, respectively. -

Understanding Land Subsidence Along the Coastal Areas of Guangdong, China, by Analyzing Multi-Track Mtinsar Data

remote sensing Article Understanding Land Subsidence Along the Coastal Areas of Guangdong, China, by Analyzing Multi-Track MTInSAR Data Yanan Du 1 , Guangcai Feng 2, Lin Liu 1,3,* , Haiqiang Fu 2, Xing Peng 4 and Debao Wen 1 1 School of Geographical Sciences, Center of GeoInformatics for Public Security, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou 510006, China; [email protected] (Y.D.); [email protected] (D.W.) 2 School of Geosciences and Info-Physics, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China; [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (H.F.) 3 Department of Geography, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221-0131, USA 4 School of Geography and Information Engineering, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-020-39366890 Received: 6 December 2019; Accepted: 12 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: Coastal areas are usually densely populated, economically developed, ecologically dense, and subject to a phenomenon that is becoming increasingly serious, land subsidence. Land subsidence can accelerate the increase in relative sea level, lead to a series of potential hazards, and threaten the stability of the ecological environment and human lives. In this paper, we adopted two commonly used multi-temporal interferometric synthetic aperture radar (MTInSAR) techniques, Small baseline subset (SBAS) and Temporarily coherent point (TCP) InSAR, to monitor the land subsidence along the entire coastline of Guangdong Province. The long-wavelength L-band ALOS/PALSAR-1 dataset collected from 2007 to 2011 is used to generate the average deformation velocity and deformation time series. Linear subsidence rates over 150 mm/yr are observed in the Chaoshan Plain. -

High Speed Rail: Wuhan Urban Garden 5-Day Trip

High Speed Rail: Wuhan Urban Garden 5-Day Trip Day 1 Itinerary Suggested Transportation Hong Kong → Wuhan High Speed Rail [Hong Kong West Kowloon Station → Wuhan Railway Station] To hotel: Recommend to stay in a hotel by the river in Wuchang District. Metro: From Wuhan Railway Hotel for reference: Station, take Metro Line 4 The Westin Wuhan Wuchang Hotel towards Huangjinkou. Address: 96 Linjiang Boulevard, Wuchang District, Wuhan Change to Line 2 at Hongshan Square Station towards Tianhe International Airport. Get off at Jiyuqiao Station and walk for about 7 minutes. (Total travel time about 46 minutes) Taxi: About 35 minutes. Enjoy lunch near the hotel On foot: Walk for about 5 minutes Restaurant for reference: Zhen Bafang Hot Pot from the hotel. Address: No. 43 & 44, Building 12-13, Qianjin Road, Wanda Plaza, Jiyu Bridge, Wuchang District, Wuhan Stand the Test of Time: Yellow Crane Tower Bus: Walk for about 4 minutes from the restaurant to Jiyuqiao Metro Station. Take bus 804 towards Nanhu Road Jiangnan Village. Get off at Yue Ma Chang Station and walk for about 6 minutes. (Total travel time about 37 minutes) Taxi: About 15 minutes. Known as “The No. 1 Tower in the World”, the Yellow Crane Tower is a landmark for Wuhan City and Hubei Province and a must-see attraction. The tower was built in the Three Kingdoms era and was named after its erection on Huangjiji, a submerged rock. Well-known ancient characters such as Li Bai, Bai Juyi, Lu You and Yue Fei had all referenced the tower in their poetry works. -

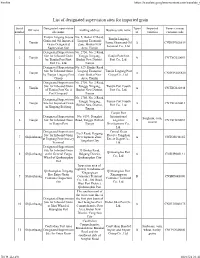

List of Designated Supervision Sites for Imported Grain

Firefox https://translate.googleusercontent.com/translate_f List of designated supervision sites for imported grain Serial Designated supervision Types Imported Venue (venue) Off zone mailing address Business unit name number site name of varieties customs code Tianjin Lingang Jiayue No. 5, Bohai 37 Road, Tianjin Lingang Grain and Oil Imported Lingang Economic 1 Tianjin Jiayue Grain and Oil A CNDGN02S619 Grain Designated Zone, Binhai New Terminal Co., Ltd. Supervision Site Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port First 2 Tianjin A CNTXG020051 by Tianjin Port First Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Co., Ltd. Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 529, Hunhe Road, Site for Inbound Grain Lingang Economic Tianjin Lingang Port 3 Tianjin A CNDGN02S620 by Tianjin Lingang Port Zone, Binhai New Group Co., Ltd. Group Area, Tianjin Designated Supervision No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Site for Inbound Grain Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 4 Tianjin A CNTXG020448 of Tianjin Port No. 4 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. Port Company Tianjin No. 2750, No. 2 Road, Designated Supervision Tanggu Xingang, Tianjin Port Fourth 5 Tianjin Site for Imported Grain A CNTXG020413 Binhai New District, Port Co., Ltd. in Xingang Beijiang Tianjin Tianjin Port Designated Supervision No. 6199, Donghai International Sorghum, corn, 6 Tianjin Site for Inbound Grain Road, Tanggu District, Logistics B CNTXG020051 sesame in Tianjin Port Tianjin Development Co., Ltd. Designated Supervision Central Grain No.9 Road, Haigang Site for Inbound Grain Reserve Tangshan 7 Shijiazhuang Development Zone, A CNTGS040165 at Jingtang Port Grocery Direct Depot Co., Tangshan City Terminal Ltd.