Thesis Draft (October Edit)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Manufacture' of News in Teh 1993 New Zealand General Election

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. The "Manufacture" of News in the New Zealand General Election 1993 A thesis presenteJ in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Human Resource Management at Massey University Judith Helen McGregor 1995 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Associate Professor Fra11k Sligo and Professor Philip Dewe, for their continued support and assistance during the research project. The study would not have been possible without the help of Annette King, the Member of Parliament for Miramar, and the former Labour leader, Mike Moore, who allowed me inside their organizations. Annette King allowed me to use her as an action research "guinea pig" and her enthusiasm for the project motivated me throughout the research. Sue Foley and Paul Jackrnan, Mr Moore's press secretaries, provided valuable feedback and explained the context of much of the election campaign roadshow. Thanks must go, too, to Lloyd Falck, Labour Party strategist and research adviser to the Leader of the Opposition. Piet de Jong, Liz Brook and Alister Browne all helped with the action research in Miramar. Dr Ted Drawneek provided invaluable help with data analysis in the content analysis sections of the research and I acknowledge the secretarial assistance of Christine Smith. I am grateful to John Harvey for his advice about contemporary journalism and for his unstinting encouragement and support. -

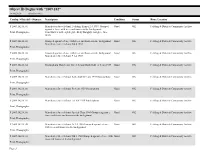

Feilding Public Library Collection

Object ID Begins with "2009.102" 14/06/2020 Matches 4033 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location P 2009.102.01.01 Manchester Street School, Feilding. Primer 2-3 1939. Grouped Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive against a fence with trees and houses in the background. Print, Photographic Front Row L to R: eighth girl - Betty Doughty, last girl - June Wells. P 2009.102.01.02 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School Std 4 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.03 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School F 1-2 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.04 Studio photo Manchester Street School Basketball A Team 1939 Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.05 Manchester Street School Basketball B Team 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.06 Manchester Street School Prefects 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.07 Manchester Street School 1st XV 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.08 Manchester Street School Special Class 1940 Grouped against a Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive fence with trees and houses in the background Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.09 Manchester Street School -

An Evolving Order the Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand 1914–2014

An Evolving Order The Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand 1914–2014 Peter Cooke An Evolving Order The Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand, 1914-2014 Peter Cooke Published by Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand, 158 The Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand © 2014 Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand The author, Peter Cooke, asserts his moral right in the work. First published 2014 This book is copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. ISBN 978-0-908960-58-3 (print copy) ISBN 978-0-908960-59-0 (electronic book) Book design by Cluster Creative CONTENTS Foreword vii Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations x Chapter 1: Beginnings 1 The arrival of New Zealand’s surveyors/engineers 1 Motivation for engineering independence 4 Local government engineers 1912 6 “One strong society” 8 Other institutions 10 Plumbers, architects, and the New Zealand Society of Civil Engineers 12 First World War 15 Chapter 2: 1920s 21 Engineers Registration Act 1924 21 Getting registered 24 The Society’s first premises 26 Perception of the Society 27 Attempting advocacy 29 What’s in a name? Early debates 30 Benevolence 32 New Zealand engineering and the Society’s history 33 Chapter 3: 1930s 37 A recurring issue: the status of engineers 37 Engineering education and qualifications 38 Earthquake engineering 40 Standardisation 42 Building bylaw 44 Professional etiquette/ethics 45 A test of ethics 47 Professional -

16. Nuclear-Free New Zealand

16 Nuclear-free New Zealand: Contingency, contestation and consensus in public policymaking David Capie Introduction On 4 June 1987, the New Zealand Parliament passed the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Act by 39 votes to 29. The legislation marked the culmination of a decades-long effort by a disparate group of peace and environmental activists to prevent nuclear weapons from entering New Zealand’s territory. More than 30 years later, the law remains in force, it has bipartisan support and it is frequently touted as a key symbol of New Zealand’s national identity. In some ways, it should be puzzling that New Zealand has come to be so closely associated with staunch opposition to nuclear arms. The country is far removed from key strategic territory and even at the height of the Cold War was one of the least likely countries anywhere to suffer a nuclear attack. The fact the adoption of the antinuclear policy led to the end of New Zealand’s alliance relationship with the United States under the Australia, New Zealand, United States Security (ANZUS) Treaty—an agreement once described as the ‘richest prize’ in New Zealand diplomacy—only adds to the puzzle (Catalinac 2010). How, then, did a group of activists 379 SUCCESSFUL PUBLIC POLICY and politicians propel an issue into the public consciousness and, despite the staunch opposition of the most powerful country in the world, work to see it enshrined in legislation? This chapter explores nuclear-free New Zealand as an example of a policy success. It does so in four parts. -

The New Zealand Azette

Issue No. 191 • 4177 The New Zealand azette WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 1 NOVEMBER 1990 Contents Government Notices 4178 Authorities and Other Agencies of State Notices 4195 Land Notices 4196 Regulation Summary 4206 Using the Gazette The New Zealand Gazette, the official newspaper of the Closing time for lodgment of notices at the Gazette Office: Government of New Zealand, is published weekly on 12 noon on Tuesdays prior to publication (except for holiday Thursdays. Publishing time is 4 p.m. periods when special advice of earlier closing times will be Notices for publication and related correspondence should be given). addressed to: Notices are accepted for publication in the next available issue, Gazette Office, unless otherwise specified. Department of Internal Affairs, Notices being submitted for publication must be a reproduced P.O. Box 805, copy of the original. Dates, proper names and signatures are Wellington. Telephone (04) 738 699 to be shown clearly. A covering instruction setting out require ments must accompany all notices. Facsimile (04) 499 1865 or lodged at the Gazette Office, Seventh Floor, Dalmuir Copy will be returned unpublished if not submitted in House, 114 The Terrace, Wellington. accordance with these requirements. 4178 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 191 Availability Government Buildings, 1 George Street, Palmerston North. The New Zealand Gazette is available on subscription from GP Publications Limited or over the counter from GP Books Cargill House, 123 Princes Street, Dunedin. Limited bookshops at: Housing Corporation Building, 25 Rutland Street, Auckland. Other issues of the Gazette: 33 Kings Street, Frankton, Hamilton. Commercial Edition-Published weekly on Wednesdays. 25-27 Mercer Street, Wellington. -

Support for Third Parties Under Plurality Rule Electoral Systems : a Public Choice Analysis of Britain, Canada, New Zealand and South Korea

SUPPORT FOR THIRD PARTIES UNDER PLURALITY RULE ELECTORAL SYSTEMS : A PUBLIC CHOICE ANALYSIS OF BRITAIN, CANADA, NEW ZEALAND AND SOUTH KOREA WON-TAEK KANG Thesis presented for Ph.D. at London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U105556 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U105556 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ti-w^s& S F 7 ^ 2 7 ABSTRACT Why do parties other than major parties survive or even flourish under plurality rule electoral systems, when according to Du verger’s law we should expect them to disappear? Why should rational voters support third parties, even though their chances of being successful are often low ? Using an institutional public choice approach, this study analyses third party voting as one amongst a continuum of choices faced by electors who pay attention both to the ideological proximity of parties, and to their perceived efficacy measured against a community-wide level of minimum efficacy. The approach is applied in detailed case study chapters examining four different third parties. -

Thesis Front 2

Nuclear New Zealand: New Zealandʼs nuclear and radiation history to 1987 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History and Philosophy of Science in the University of Canterbury by Rebecca Priestley, BSc (hons) University of Canterbury August 2010 Table of contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgements 2 Chapter 1 Nuclear-free New Zealand: Reality or a myth to be debunked? 3 Chapter 2 The radiation age: Rutherford, New Zealand and the new physics 25 Chapter 3 The public are mad on radium! Applications of the new science 45 Chapter 4 Some fool in a laboratory: The atom bomb and the dawn of the nuclear age 80 Chapter 5 Cold War and red hot science: The nuclear age comes to the Pacific 110 Chapter 6 Uranium fever! Uranium prospecting on the West Coast 146 Chapter 7 Thereʼs strontium-90 in my milk: Safety and public exposure to radiation 171 Chapter 8 Atoms for Peace: Nuclear science in New Zealand in the atomic age 200 Chapter 9 Nuclear decision: Plans for nuclear power 231 Chapter 10 Nuclear-free New Zealand: The forging of a new national identity 257 Chapter 11 A nuclear-free New Zealand? The ideal and the reality 292 Bibliography 298 1 Abstract New Zealand has a paradoxical relationship with nuclear science. We are as proud of Ernest Rutherford, known as the father of nuclear science, as of our nuclear-free status. Early enthusiasm for radium and X-rays in the first half of the twentieth century and euphoria in the 1950s about the discovery of uranium in a West Coast road cutting was countered by outrage at French nuclear testing in the Pacific and protests against visits from American nuclear-powered warships. -

Aotearoa/New Zealand Peace Foundation History the First 20 Years

Aotearoa/New Zealand Peace Foundation History The First 20 Years Contents: Foreword by Kate Dewes………………………………………………………………….....3 Introduction by Katherine Knight and Wendy John……………………………………….4 Chapter One: In the Beginning…………………………………………………………….6 Chapter Two: The Way Forward……………………………………………………….....16 Chapter Three: Responding to International Tension……………………………......26 Chapter Four: International Year of Peace and Nuclear Free New Zealand……....37 Chapter Five: Adjusting the Focus………………………………………………..……..43 Chapter Six: Peace Education in the Schools……………………………………...…53 Chapter Seven: After the Reforms………………………………………………….…….64 Chapter Eight: A Chair of Peace Studies in Tertiary Institutions……………….….70 Chapter Nine: The Media Peace Prize (Awards)…………………………………….....77 Chapter Ten: The Annual Peace Lecture………………………………………………..85 Chapter Eleven: 1995 – 2000 Expansion and Change……………………...…………93 Postscript: Christchurch and Wellington Offices by Kate Dewes………………...…96 2 Foreword This history of the Peace Foundation’s first 20 years was drafted by Katherine Knight and Wendy John between 1994 and 2010 in the hope that it could be published as a book. Sadly, during that time Kath died and Wendy left the Peace Foundation. Now, in 2018, as I head towards formal retirement, it falls to me as one of the few original Peace Foundation members with an historical overview of the organisation, and the draft documents and photos still on my computer system, to edit and publish this history online for future generations. My understanding is that a University of Auckland MA student, Martin Wilson, did the primary research and helped draft chapters during 1994-5. He sought input from a range of members around the country. The draft was not completed in places, so I have tried to fill in the gaps using my fairly extensive Christchurch Peace Foundation archives. -

Hobbling the News

Hobbling the News A study of loss of freedom of information as a presumptive right for public-interest journalists in Aotearoa New Zealand Greg Treadwell 2018 School of Communication Studies A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Primary Supervisor: Associate Professor Verica Rupar Secondary Supervisor: Associate Professor Donald Matheson ii Abstract Public-interest journalism is widely acknowledged as critical in any attempt at sustaining actually-existing democracy and is reliant on access to State-held information for its effectiveness. The success of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Official Information Act 1982 contributed to domestic and international constructions of the nation as among the most politically transparent on Earth. Early narratives, partially heroic in character and woven primarily by policy and legal scholars, helped sophisticate early understanding of the notably liberal disclosure law. However, they came to stand in stark contrast to the powerful stories of norm-based newsroom culture, in which public-interest journalists making freedom-of-information (FOI) requests bemoaned an impenetrable wall of officialdom. Set against a literature that validates its context, inquiry and method, this thesis explores those practice-based accounts of FOI failures and their implications for public-interest journalism, and ultimately political transparency, in Aotearoa New Zealand. It reconstructs FOI as a human right, defines its role in democracy theory and traverses the distance between theory and actually-existing FOI. The research employs field theory in its approach to FOI as a site of inter-field contestation, revealing that beyond the constitutional niceties of disclosure principles, agents of the omnipotent field of political power maintain their status through, in part, the suppression of those principles. -

"2009.204" and Accession# Less Than Or Equal to "2009.224" 14/06/2020 Matches 4090

Accession# Greater than or equal to "2009.204" and Accession# Less than or equal to "2009.224" 14/06/2020 Matches 4090 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location A 2009.204.01 A Postcard View of The Old Post Office side of the Square, Fair OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Feilding, with the Clock Tower on the Post Office. (no date). The Postcard Memorial in the Centre of The Square commemorates the Boer War. The View shows several other businesses and some of the Gardens in the Square. L 2009.204.02 Book - Feilding Agricultural High School war memorial volume / Good OK FDCA Library compiled by Feilding Agricultural High School Old Pupils' Book Association. published in Feilding for Subscribers by Feilding Agricultural High School Old Pupils' Association, 1948. Foreword signed by President of F.A.H.S.O.P.A. Tui Mayo. Memorial to the forty-six Old Boys who gave their lives in World War Two. A total of 441 old pupils served overseas in the War, including seven Old Girls. Extracts from letters received by the school. Printed by Coulls Somerville Wilkie Ltd Dunedin. Foreword by T. A. Mayo President F.A.H.S.O.P.A. 16 June 1948. Armed forces, Correspondence, Letters, Memorial works, Memorials, Missing in action, Rolls of Honour, Schools, Schools, Boarding, War, casualties, World War II P 2009.204.03 Black and white photograph of the Old pupils from Manchester Excellent OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Street School 1925-1934 taken at the 90th Jubilee. Some names on Print, Photographic back of photo: Right-Left: Back Row 1. -

Changing New Zealand's Electoral Law 1927

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Consensus Gained, Consensus Maintained? Changing New Zealand’s Electoral Law 1927 – 2007 A Thesis Submitted to Victoria University of Wellington In Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science James Christmas 2010 To JMC 2 Acknowledgments In submitting this work, I acknowledge a substantial debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Elizabeth McLeay, for her guidance, constant attention and interest. For their encouragement, I thank my parents. For his patience, this thesis is dedicated to James. James Christmas Christchurch 2010 3 Contents Abstract 5 List of Tables and 6 Figures Chapter One Introduction 7 Chapter Two The Electoral Law in Context 15 Chapter Three Milestones: Three Eras of Electoral 27 Amendment? Chapter Four Parliament and Electoral Rules 49 Chapter Five Boundaries, Franchise and Registration 70 Chapter Six Election Administration and Electioneering 92 Chapter Seven Assessing Trends and Motivations 112 Chapter Eight Conclusion 132 Appendix A Acts Affecting the Electoral Law 1927 – 2007 135 (in chronological order) Appendix B Unsuccessful Electoral Reform Bills, 1927 – 154 2007 (in chronological order) Bibliography 162 4 Abstract In the eighty years between the passage of New Zealand’s first unified Electoral Act in 1927, and the passage of the Electoral Finance Act 2007, the New Zealand Parliament passed 66 acts that altered or amended New Zealand’s electoral law. One central assumption of theories of electoral change is that those in power only change electoral rules strategically, in order to protect their self-interest. -

Mmp and the Constitution

© New Zealand Centre for Public Law and contributors Faculty of Law Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand June 2009 The mode of citation of this journal is: (2009) 7 NZJPIL (page) The previous issue of this journal is volume 6 number 2, December 2008 ISSN 11763930 Printed by Geon, Brebner Print, Palmerston North Cover photo: Robert Cross, VUW ITS Image Services CONTENTS SPECIAL CONFERENCE ISSUE: MMP AND THE CONSTITUTION Foreword Dean R Knight...........................................................................................................................vii "Who's the Boss?": Executive–Legislature Relations in New Zealand under MMP Ryan Malone............................................................................................................................... 1 The Legal Status of Political Parties under MMP Andrew Geddis.......................................................................................................................... 21 Experiments in Executive Government under MMP in New Zealand: Contrasting Approaches to MultiParty Governance Jonathan Boston and David Bullock........................................................................................... 39 MMP, Minority Governments and Parliamentary Opposition André Kaiser............................................................................................................................. 77 Public Attitudes towards MMP and Coalition Government Raymond Miller and Jack Vowles..............................................................................................