Changing New Zealand's Electoral Law 1927

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storm in a Pee Cup Drug-Related Impairment in the Workplace Is Undoubtedly a Serious Issue and a Legitimate Concern for Employers

Mattersof Substance. august 2012 Volume 22 Issue No.3 www.drugfoundation.org.nz Storm in a pee cup Drug-related impairment in the workplace is undoubtedly a serious issue and a legitimate concern for employers. But do our current testing procedures sufficiently balance the need for accuracy, the rights of employees and the principles of natural justice? Or does New Zealand currently have a drug testing problem? CONTENTS ABOUT A DRUG Storm in 16 COVER STORY FEATURE a pee cup STORY CoveR: More than a passing problem 06 32 You’ve passed your urine, but will you pass your workplace drug test? What will the results say about your drug use and level of impairment? Feature ARTICLE OPINION NZ 22 28 NEWS 02 FEATURES Become 14 22 26 30 a member Bizarre behaviour Recovery ruffling Don’t hesitate A slug of the drug Sensible, balanced feathers across the Just how much trouble can What’s to be done about The NZ Drug Foundation has been at reporting and police work Tasman you get into if you’ve been caffeine and alcohol mixed the heart of major alcohol and other reveal bath salts are Agencies around the world taking drugs, someone beverages, the popular drug policy debates for over 20 years. turning citizens into crazy, are newly abuzz about overdoses and you call poly-drug choice of the During that time, we have demonstrated violent zombies! recovery. But do we all 111? recently post-pubescent? a strong commitment to advocating mean the same thing, and policies and practices based on the best does it matter? evidence available. -

Journal Is: (2009) 7 NZJPIL (Page)

© New Zealand Centre for Public Law and contributors Faculty of Law Victoria University of Wellington PO Box 600 Wellington New Zealand June 2009 The mode of citation of this journal is: (2009) 7 NZJPIL (page) The previous issue of this journal is volume 6 number 2, December 2008 ISSN 11763930 Printed by Geon, Brebner Print, Palmerston North Cover photo: Robert Cross, VUW ITS Image Services CONTENTS SPECIAL CONFERENCE ISSUE: MMP AND THE CONSTITUTION Foreword Dean R Knight...........................................................................................................................vii "Who's the Boss?": Executive–Legislature Relations in New Zealand under MMP Ryan Malone............................................................................................................................... 1 The Legal Status of Political Parties under MMP Andrew Geddis.......................................................................................................................... 21 Experiments in Executive Government under MMP in New Zealand: Contrasting Approaches to MultiParty Governance Jonathan Boston and David Bullock........................................................................................... 39 MMP, Minority Governments and Parliamentary Opposition André Kaiser............................................................................................................................. 77 Public Attitudes towards MMP and Coalition Government Raymond Miller and Jack Vowles.............................................................................................. -

Martyn Finlay Memorial Scholarship

Martyn Finlay Memorial Scholarship Code: 366 Faculty: Law Applicable study: LLB Part III Closing date: 31 August Tenure: One year For: Financial Assistance Number on offer: One Offer rate: Annually Value: Up to $2,400 Description In memory of the late Hon Dr Allan Martyn Finlay QC, Member of Parliament for the North Shore 1946–1949, Vice President of the New Zealand Labour Party from 1956–1958, President from 1958–1963, Member for Waitakere 1963–1978, Attorney General and Minister of Justice in the Labour Government of 1972–1975 and in 1973-1974 led the New Zealand case against the French nuclear testing at Muroroa. He was a long time member of the University of Auckland Council. The main purpose of the Scholarship is to enable academically able students who are demonstrably suffering financial hardship to continue their undergraduate Law studies in Part Three at the University of Auckland. Selection process - Application is made to the Scholarships Office - A Selection Committee assesses the applications - The Scholarship is awarded by the University of Auckland Council on the recommendation of the Selection Committee Regulations 1. The Scholarship will be known as the Martyn Finlay Memorial Scholarship. 2. One Scholarship will be awarded each year for a period of one year and will be of the value of $2,400. 3. The Scholarship will be awarded to a candidate who is enrolled in Part III of an undergraduate Law Degree and has paid the fees, or arranged to pay the fees, for full-time study. 4. Selection will be based on academic merit, demonstrable financial hardship and commitment to the community. -

The Politics of Post-War Consumer Culture

New Zealand Journal of History, 40, 2 (2006) The Politics of Post-War Consumer Culture THE 1940s ARE INTERESTING YEARS in the story of New Zealand’s consumer culture. The realities of working and spending, and the promulgation of ideals and moralities around consumer behaviour, were closely related to the political process. Labour had come to power in 1935 promising to alleviate the hardship of the depression years and improve the standard of living of all New Zealanders. World War II intervened, replacing the image of increasing prosperity with one of sacrifice. In the shadow of the war the economy grew strongly, but there remained a legacy of shortages at a time when many sought material advancement. Historical writing on consumer culture is burgeoning internationally, and starting to emerge in New Zealand. There is already some local discussion of consumption in the post-war period, particularly with respect to clothing, embodiment and housing.1 This is an important area for study because, as Peter Gibbons points out, the consumption of goods — along with the needs they express and the desires they engender — deeply affects individual lives and social relationships.2 A number of aspects of consumption lend themselves to historical analysis, including the economic, the symbolic, the moral and the political. By exploring the political aspects of consumption and their relationships to these other strands, we can see how intense contestation over the symbolic meaning of consumption and its relationship to production played a pivotal role in defining the differences between the Labour government and the National opposition in the 1940s. -

The Literati “ Mail Us at [email protected] 10

Vol : 02 From the desk of COO On the forefront and in alignment with the fabric of our organization we have initiated a massive online subject specific training for all educators PAN India which has reflected a great effectiveness in terms of enrolment of educators and using the strategies during the online Mr. Raju Babu Sinha teaching by our educators. Chief Operating Officer Zee Learn Limited We will keep you fully occupied with academic events and cultural extravaganzas and ensure that you will have all the ingredients with which to create one of the I hope you are well and safe during this most magical and exponentially rewarding experiences uncertain time ! of your life at MLZS. As we embark on studying from home , I wanted to You may be feeling a range of emotions with this abrupt let you know a few things ZLL is doing to provide change to your learning and the disruption in your life. I extensive support. This is an unprecedented event understand that your emotions may have turned into and we’re working to be as agile as possible in uncertainty, stress or sadness. The most important getting our students, parents, and educators the message I want to send you is this- all of us at ZLL want resources and guidance they need through our you to feel supported. The trusted team who know you in learning portals. your school are going to provide you the academic and Our team is communicating on a regular basis with socio-emotional supports you may need. all members of our schools via our website, email, Let’s all be kind to one another, patient, and proactive video and phone calls about the updates on the about our own health. -

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

Peter Fraser

N E \V z_E A L A N D S T U D I E S 1!!J BOOK 'RJVIEW by SiiiiOII sheppard Peter Fraser: Master Politician Fraser made more important decisions in more interesting times Margaret Clark (Ed), The Dunmore Press, 1998, $29.95 than Holyoake ever did. ARL!ER THIS YEAR I con International Relations at Victoria Congratulations are due to the E ducted a survey among University, the book is derived from organisers of the conference for academics and other leaders in their a conference held in August 1997, their diligence in assembling a fields asking them to give their part of a series being conducted by roster of speakers capable of appraisal of New Zealand's providing such a broad Prime Ministers according spectrum of perspectives on to the extent to which they Fraser. This multi-faceted made a positive contribu approach pays dividends in tion to the history of the that it reflects the depth of country. From the replies I Fraser's character and the was able to establish a breadth of his contribution to ranking of the Prime New Zealand history. Ministers, from greatest to The first three phases of least effective. Fraser's political career are It was no surprise that discussed; from early Richard Seddon finished in socialist firebrand, to key first place. But I was lieutenant in the first Labour intrigued by the runner up. Government, to wartime It was not the beloved Prime Minister and interna Michael Joseph-Savage, nor tional statesman at the the inspiring Norman Kirk, founding of the United or the long serving Sir Keith Nations. -

Regional Transport Committee Agenda June 2019

Regional Transport Committee Wednesday 12 June 2019 11.00am Taranaki Regional Council, Stratford Regional Transport Committee - Agenda Agenda for the meeting of the Regional Transport Committee to be held in the Taranaki Regional Council chambers, 47 Cloten Road, Stratford, on Wednesday 12 June 2019 commencing at 11.00am. Members Councillor C S Williamson (Committee Chairperson) Councillor M J McDonald (Committee Deputy Chairperson) Mayor N Volzke (Stratford District Council) Mayor R Dunlop (South Taranaki District Council) Mr R I'Anson (Acting NZ Transport Agency) Apologies Councillor H Duynhoven (New Plymouth District Council) Notification of Late Items Item Page Subject Item 1 3 Confirmation of Minutes Item 2 8 Minutes of the Regional Transport Advisory Group Item 3 19 Notes of SH3 Working Party Item 4 39 Request to Vary the RLTP Item 5 49 Regional Road Safety Update Item 6 65 NZTA regional report Item 7 75 Enhanced drug impaired driver testing Item 8 85 Renewal of Regional Public Transport Plan (RPTP) Item 9 90 Passenger Transport Operational Update to 30 March 2019 Item 10 104 Correspondence and information items 2 Regional Transport Committee - Confirmation of Minutes Agenda Memorandum Date 12 June 2019 Memorandum to Chairperson and Members Regional Transport Committee Subject: Confirmation of Minutes – 27 March 2019 Approved by: M J Nield, Director-Corporate Services B G Chamberlain, Chief Executive Document: 2270559 Resolve That the Regional Transport Committee of the Taranaki Regional Council: a) takes as read and confirms the minutes and resolutions of the Regional Transport Committee meeting of the Taranaki Regional Council held in Taranaki Regional Council chambers, 47 Cloten Road, Stratford, on Wednesday 27 March 2019 at 11.00am b) notes the recommendations therein were adopted by the Taranaki Regional Council on 9 April 2019. -

+Tuhinga 27-2016 Vi:Layout 1

27 2016 2016 TUHINGA Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa The journal of scholarship and mätauranga Number 27, 2016 Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is a peer-reviewed publication, published annually by Te Papa Press PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand TE PAPA ® is the trademark of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Papa Press is an imprint of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga is available online at www.tepapa.govt.nz/tuhinga It supersedes the following publications: Museum of New Zealand Records (1171-6908); National Museum of New Zealand Records (0110-943X); Dominion Museum Records; Dominion Museum Records in Ethnology. Editorial board: Catherine Cradwick (editorial co-ordinator), Claudia Orange, Stephanie Gibson, Patrick Brownsey, Athol McCredie, Sean Mallon, Amber Aranui, Martin Lewis, Hannah Newport-Watson (Acting Manager, Te Papa Press) ISSN 1173-4337 All papers © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2016 Published June 2016 For permission to reproduce any part of this issue, please contact the editorial co-ordinator,Tuhinga, PO Box 467, Wellington. Cover design by Tim Hansen Typesetting by Afineline Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Number 27, 2016 Contents A partnership approach to repatriation: building the bridge from both sides 1 Te Herekiekie Herewini and June Jones Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments and corrections 10 Jeremy Coote Response to ‘Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments 20 and corrections’ Chris D. -

The New Zealand Azette

Issue No. 132 • 2729 The New Zealand azette WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 2 AUGUST 1990 [contents Vice Regal 2730 Parliamentary Summary 2730 Government Notices 2732 Authorities and Other Agencies of State Notices 2741 Land Notices 2742 Regulation Summary 2749 General Section .. 2750 Using the Gazette The New Zealand Gazette, the official newspaper of the Closing time for lodgment of notices at the Gazette Office: Government of New Zealand, is published weekly on 12 noon on Tuesdays prior to publication (except for holiday Thursdays. Publishing time is 4 p.m. periods when special advice of earlier closing times will be Notices for publication and related correspondence should be given) . addressed to: Notices are accepted for publication in the next available issue, Gazette Office, unless otherwise specified . Department of Internal Affairs, P.O. Box 805, Notices being submitted for publication must be a reproduced Wellington. copy of the original. Dates, proper names and signatures are Telephone (04) 738 699 to be shown clearly. A covering instruction setting out require Facsimile (04) 499 1865 ments must accompany all notices. or lodged at the Gazette Office, Seventh Floor, Dalmuir Copy will be returned unpublished if not submitted in House, 114 The Terrace, Wellington. accordance with these requirements. 2730 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 132 Availability Government Buildings, 1 George Street, Palmerston North. The New Zealand Gazette is available on subscription from the Government Printing Office Publications Division or over the Cargill House, 123 Princes Street, Dunedin. counter from Government Bookshops at: Housing Corporation Building, 25 Rutland Street, Auckland. Other issues of the Gazette: 33 Kings Street, Frankton, Hamilton. -

The 'Manufacture' of News in Teh 1993 New Zealand General Election

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. The "Manufacture" of News in the New Zealand General Election 1993 A thesis presenteJ in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Human Resource Management at Massey University Judith Helen McGregor 1995 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Associate Professor Fra11k Sligo and Professor Philip Dewe, for their continued support and assistance during the research project. The study would not have been possible without the help of Annette King, the Member of Parliament for Miramar, and the former Labour leader, Mike Moore, who allowed me inside their organizations. Annette King allowed me to use her as an action research "guinea pig" and her enthusiasm for the project motivated me throughout the research. Sue Foley and Paul Jackrnan, Mr Moore's press secretaries, provided valuable feedback and explained the context of much of the election campaign roadshow. Thanks must go, too, to Lloyd Falck, Labour Party strategist and research adviser to the Leader of the Opposition. Piet de Jong, Liz Brook and Alister Browne all helped with the action research in Miramar. Dr Ted Drawneek provided invaluable help with data analysis in the content analysis sections of the research and I acknowledge the secretarial assistance of Christine Smith. I am grateful to John Harvey for his advice about contemporary journalism and for his unstinting encouragement and support. -

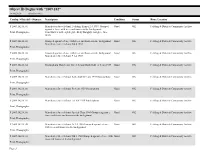

Feilding Public Library Collection

Object ID Begins with "2009.102" 14/06/2020 Matches 4033 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location P 2009.102.01.01 Manchester Street School, Feilding. Primer 2-3 1939. Grouped Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive against a fence with trees and houses in the background. Print, Photographic Front Row L to R: eighth girl - Betty Doughty, last girl - June Wells. P 2009.102.01.02 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School Std 4 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.03 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School F 1-2 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.04 Studio photo Manchester Street School Basketball A Team 1939 Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.05 Manchester Street School Basketball B Team 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.06 Manchester Street School Prefects 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.07 Manchester Street School 1st XV 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.08 Manchester Street School Special Class 1940 Grouped against a Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive fence with trees and houses in the background Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.09 Manchester Street School