Jedburgh Abbey Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Galashiels and Selkirk Almanac and Directory for 1898

UMBRELLAS Re-Covered in One Hour from 1/9 Upwards. All Kinds of Repairs Promptly Executed at J. R. FULTON'S Umbrella Ware- house, 51 HIGH STREET, Galashiels. *%\ TWENTIETH YEAR OF ISSUE. j?St masr Ok Galasbiels and Selkirk %•* Almanac and Directorp IFOIR, X898 Contains a Variety of Useful information, County Lists for Roxburgh and Selkirk, Local Institutions, and a Complete Trade Directory. Price, - - One Penny. PUBLISHED BY JOH3ST ZMZCQ-CTiEiE] INT, Proprietor of the "Scottish Border Record," LETTERPRESS and LITHOGRAPHIC PRINTER, 25 Channel Street, Galashiels. ADVERTISEMENT. NEW MODEL OF THE People's Cottage Piano —^~~t» fj i «y <kj»~ — PATERSON & SONS would draw Special Attention to this New Model, which is undoubtedly the Cheapest and Best Cottage Piano ever offered, and not only A CHEAP PIANO, but a Thoroughly Reliable Instrument, with P. & Sons' Guakantee. On the Hire System at 21s per Month till paid up. Descriptive Price-Lists on Application, or sent Free by Post. A Large Selection of Slightly-used Instruments returned from Hire will be Sold at Great Reductions. Sole Agents for the Steinway and Bechstein Pianofortes, the two Greatest Makers of the present century. Catalogues on Application. PATEESON <Sc SONS, Musicsellers to the Queen, 27 George Street, EDINBURGH. PATERSON & SONS' Tuners visit the Principal Districts of Scotland Quarterly, and can give every information as to the Purchase or Exchanne of Pianofortes. Orders left with John McQueen, "Border Record" Office, Galashiels, shall receive prompt attention. A life V'C WELLINGTON KNIFE POLISH. 1 *™ KKL f W % Prepared for Oakey's Knife-Boards and all Patent Knife- UfgWa^^""Kmm ^"it— I U Clea-iing Machines. -

Welcome to Midlothian (PDF)

WELCOME TO MIDLOTHIAN A guide for new arrivals to Midlothian • Transport • Housing • Working • Education and Childcare • Staying safe • Adult learning • Leisure facilities • Visitor attractions in the Midlothian area Community Learning Midlothian and Development VISITOr attrACTIONS Midlothian Midlothian is a small local authority area adjoining Edinburgh’s southern boundary, and bordered by the Pentland Hills to the west and the Moorfoot Hills of the Scottish Borders to the south. Most of Midlothian’s population, of just over 80,000, lives in or around the main towns of Dalkeith, Penicuik, Bonnyrigg, Loanhead, Newtongrange and Gorebridge. The southern half of the authority is predominantly rural, with a small population spread between a number of villages and farm settlements. We are proud to welcome you to Scotland and the area www.visitmidlothian.org.uk/ of Midlothian This guide is a basic guide to services and • You are required by law to pick up litter information for new arrivals from overseas. and dog poo We hope it will enable you to become a part of • Smoking is banned in public places our community, where people feel safe to live, • People always queue to get on buses work and raise a family. and trains, and in the bank and post You will be able to find lots of useful information on office. where to stay, finding a job, taking up sport, visiting tourist attractions, as well as how to open a bank • Drivers thank each other for being account or find a child-minder for your children. considerate to each other by a quick hand wave • You can safely drink tap water There are useful emergency numbers and references to relevant websites, as well as explanations in relation to your rights to work. -

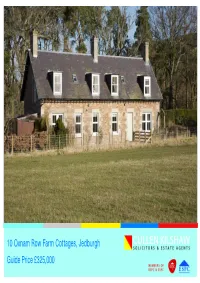

10 Oxnam Row.Pmd

10 Oxnam Row Farm Cottages, Jedburgh Guide Price £325,000 10 Oxnam Row is a well-presented detached cottage which LOCATION DIRECTIONS sits amidst stunning Scottish Borders countryside above Oxnam is an attractive small Borders village set amidst rolling From the A68 heading north take the right turn in Camptown, Oxnam Water and within easy reach of the historic market farmland yet just a short distance from Jedburgh. The mainly just before the bridge over Jed Water. Follow this road for 3.4 residential village offers an active community-owned village town of Jedburgh. The property was originally two miles and then turn right into the driveway and the entrance hall. A short drive away is the popular market town of Jedburgh gates for number 10 Oxnam Row will be straight ahead. cottages which have been combined to provide a bright where there is a good range of amenities including a wide and spacious home with high-quality fixtures and fittings range of shops, professional services, schools, health centre, supermarket, restaurants, cafes and a wide range of leisure including handmade solid oak doors. The front door opens amenities. Jedburgh is one of the most historic towns in the into an entrance hall which has a large storage cupboard Scottish Borders with many fine buildings including the Abbey. and stairs to the upper floor. The bright, dual aspect The main A68 is a short distance from the property which makes many of the surrounding Borders towns and villages within easy reception hall has two window seats offering stunning open commuting distance and providing access to Edinburgh and rural views; this room has flexible use as either a second Newcastle. -

Invitation and Itinerary

The Scotland Borders England July 17-23, 2009 Invitation and Itinerary We hope you can join us in Scotland and England for exploration by bike of "The Borders" region of southern Scotland and northern England. In the guidebook Scotland the Best, The Borders is ranked as the #1 place to bike in Scotland. Touring by bike is the best venue we know for combining the outdoors, exercise, camaraderie among fellow cyclists, deliberately slow travels, and a dash of serendipitous adventure. We hold the fellowship and good times on past international tours as very special memories. Veterans and first time adventurers are encouraged to join us as we travel to an as yet undiscovered cycling paradise, before the word gets out! Mary and Allen Turnbull In 2009 Scotland will host its first ever Homecoming year which has been created to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns. This will be a special year for Scots, those of Scotch ancestry, and all those who love Scotland. It will be fantastic year to "come home." www.homecomingscotland2009.com What is the best way to participate in this countrywide celebration? By bike, of course! So in July we will bike by ancient abbeys, castles, baronial mansions, gently flowing rivers, and picturesque villages as we start in western Scotland and end in England at the North Sea. The Borders include the four shires of Peebles, Berwick, Selkirk, and Roxburgh in Scotland, plus Northumberland in England. Insight Guides says "It [The Borders] is one of Europe’s last unspoilt areas." One morning we’ll put on our walking shoes and hike the Four Abbeys Way as we make a 21st Century pilgrimage to Jedburgh Abbey. -

Denholm Hall Farm East Draft Planning Brief

This page is intentionally blank. Denholm Hall Farm East Development Brief Contents Introduction 2 Local context 3 Policy context 4 Background 6 Site analysis 6 Opportunities & constraints 7 Development vision 9 Development contributions 11 Submission requirements 12 Contacts 14 Alternative format/language paragraph 16 Figure 1 Denholm Hall Farm East Site 2 Figure 2 Local context 3 Figure 3 Site analysis of key issues 5 Figure 4 Development vision 8 1 Denholm Hall Farm East Development Brief Introduction This brief sets out the main objectives and issues to be addressed in the development of two adjacent housing sites: - Denholm Hall Farm (RD4B); and - Denholm Hall Farm East (ADENH001) The sites are located on the north east edge of Denholm Village and the boundaries are shown on the aerial photograph in Figure 1. The brief provides a framework for the future development of the sites which are allocated for housing in the Consolidated Scottish Borders Local Plan 2011. The brief identifies where detailed attention to specific issues is required and where developer contributions will be sought. The brief should be read alongside relevant national, strategic and local planning guidance, a selection of which is provided on page 4, and should be a material consideration for any planning application submitted for the site. The development brief should be read in conjunction with the developer guidance in Annex A ???? Figure 1—Denholm Hall Farm East housing site - aerial view 2 Denholm Hall Farm East Development Brief Local context Figure 2—Local Context Denholm is situated in the central Borders, mid-way between Hawick and Jedburgh on the A698. -

4 Pleasants Steading

4 Pleasants Steading Oxnam, Jedburgh, TD8 6QZ Wonderful Architecturally Designed Home In The Picturesque Hamlet Of Pleasants. Impressive Room Sizes Exquisitely Presented Throughout. Panoramic Rolling Hillside Views This Is Country Living At Its Best THE PROPERTY secondary school. The historical Royal Burgh of Jedburgh lies just ten COUNCIL TAX An individual architect designed property which has a modern interior, miles north of the border with England, and is well situated with swift Band F. but externally remains sympathetic to its rural surroundings road links to both major airports at Edinburgh and Newcastle, with . the main East Coast railway 35 miles distant at Berwick upon Tweed. ENERGY EFFICIENCY This detached stone built home is in immaculate condition with an Ideal for a commuter lying just off the A68 providing easy travel to Rating C. interior layout which gives great attention to natural light and the use further Border towns and the recently opened Borders railway just 25 of space. There are understated elements of quality from the stone minutes away. FLOORSPACE frontage and double doors to the oak flooring to the hall, lounge and Total floorspace 165sq.m. stairway. The plot is exceptionally generous with a well stocked wrap ACCOMMODATION LIST around garden and large graveled drive. Reception Hall, Living & Dining Room, Breakfasting Kitchen, Shower Room, Two Double Bedrooms, Both Ensuite. VIDEO TOUR AVAILABLE There is a natural flow through the ground floor of theoper pr ty, from https://youtu.be/up6GG45TXKU the impressive reception hall and sweeping stairway, double doors HIGHLIGHTS connect to the extensive living and dining area. This is complemented by the contemporary breakfast kitchen and a modern downstairs • Premier semi-rural location. -

Dryburgh Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 141 Designations: Scheduled Monuent (90103); Listed building (LB15114); Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00145) Taken into State care: 1919 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2011 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DRYBURGH ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DRYBURGH ABBEY SYNOPSIS Dryburgh Abbey comprises the ruins of a Premonstratensian abbey, founded in 1150 by Hugh de Morville, constable of Scotland. The upstanding remains incorporate fine architecture from the 12th, 13th and 15th centuries. Following the Protestant Reformation (1560) the abbey passed through several secular hands, until coming into the possession of David Erskine, 11th earl of Buchan, who recreated the ruin as the centrepiece of a splendid Romantic landscape. Buchan, Sir Walter Scott and Field-Marshal Earl Haig are all buried here. While a greater part of the abbey church is now gone, what does remain - principally the two transepts and west front - is of great architectural interest. The cloister buildings, particularly the east range, are among the best preserved in Scotland. The chapter house is important as containing rare evidence for medieval painted decoration. The whole site, tree-clad and nestling in a loop of the River Tweed, is spectacularly beautiful and tranquil. -

Jedburgh Tow Ur H Town T N Trail

je d b u r gh t ow n t ra il . jed bu rgh tow n tr ail . j edburgh town trail . jedburgh town trail . jedburgh town trail . town trail . jedb urgh tow n t rai l . je dbu rgh to wn tr ail . je db ur gh to wn tra il . jedb urgh town trail . jedburgh town jedburgh je db n trail . jedburgh town trail . jedburgh urg gh tow town tr h t jedbur ail . jed ow trail . introductionburgh n tr town town ail . burgh trail jedb il . jed This edition of the Jedburgh Town Trail has be found within this leaflet.. jed As some of the rgh urgh tra been revised by Scottish Borders Council sites along the Trail are houses,bu rwe ask you to u town tra rgh town gh tow . jedb il . jedbu working with the Jedburgh Alliance. The aim respect the owners’ privacy. n trail . je n trail is to provide the visitor to the Royal Burgh of dburgh tow Jedburgh with an added dimension to local We hope you will enjoy walking Ma rk et history and to give a flavour of the town’s around the Town Trail P la development. and trust that you ce have a pleasant 1 The Trail is approximately 2.5km (1 /2 miles) stay in Jedburgh long. This should take about two hours to complete but further time should be added if you visit the Abbey and the Castle Jail. Those with less time to spare may wish to reduce this by referring to the Trail map which is found in the centre pages. -

The Cranagh Ancrum Jedburgh TD8 6XA

The Cranagh Ancrum Jedburgh TD8 6XA .co.uk Therightmove UK’s number one property website Ref GC1023 The Cranagh Ancrum, Jedburgh, TD8 6XA A contemporary home set in a quiet backwater within the very popular village of Local facilities include schools for all age groups including the Grammar school at Master Bedroom Ancrum and enjoying far reaching views over open farmland Jedburgh, a wide range of shopping outlets in the neighbouring market towns of 6.13m x 3.75m (20’2”x 12’4”) Gaslashiels, Kelso and Hawick and the area is renown for its recreational and Located to the rear and overlooking mature wooded area and farmland. Range of • Two large reception rooms sporting facilities. modern wood finish wardrobes and sliding doors. Exposed beam ceiling and • Five Bedrooms (2 En suite) halogen spot lighting. • Large fitted kitchen Accommodation • Integral double garage En Suite Shower room Entrance Hall Ceramic tiled floor, Fully fitted shower screen and shower unit with part fully tiled Description Attractive slate floor, recessed ceiling lighting, walk in storage cupboard. Deep walls. Modern flat styled wash basin, low suite wc. The Cranagh is set in a slightly elevated position within a generous plot and has built in hall robe with central heating control panel, feature pine central staircase. been designed with the main reception rooms at first floor level to take full Radiator. Ground Floor advantage of the beautiful open views. Built in 2006 to a generous floor plan, the Rear Hall leading to house has underfloor central heating complimented by double glazing and there Galleried Landing are many unusual features incorporated into the design. -

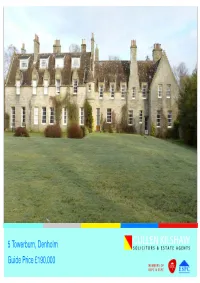

5 Towerburn, Denholm Guide Price £190,000

5 Towerburn, Denholm Guide Price £190,000 Set within generous grounds this impressive LOCATION DIRECTIONS Towerburn is located just outside the popular Borders village Travelling towards Denholm on the A698 from the Jedburgh and spacious Mansion House apartment of Denholm and lies around 7 miles from both Jedburgh and (A68) direction, turn left where signposted for Bedrule and would be ideal as main residence or indeed Hawick, enjoying easy access to the main A68 trunk road follow the road until a Y junction and veer right, signposted for as a second home. Accessed by a sweeping through the Borders. The village of Denholm is very picturesque Towerburn. Continue along this road until a turning on the offering a range of day to day facilities including a primary right through stone pillars into Towerburn. tree lined driveway, it is set within beautifully school, pubs, cafe, restaurant and village shop with a wider For Sat Nav users the post code is TD9 8TB. landscaped, extensive grounds well stocked selection of facilities available in Jedburgh and Hawick. The village has a very active community and is ideally placed for with mature trees and shrubs, providing a those who enjoy country pursuits. The new Waverley rail link lovely tranquil setting with superb views over to Edinburgh from Tweedbank can be reached in around 30 minutes from Towerburn. the surrounding Borders countryside. The property of fers a spacious and versatile layout, presented in immaculate order throughout and benefits from an abundance of attractive features. Viewing recommended to fully appreciate. SHARED ENTRANCE HALL LOUNGE KITCHEN THREE BEDROOMS BATHROOM BEAUTIFUL GARDEN GROUNDS CELLAR PARKING Guide Price £190,000 . -

Jedburgh Abbey Church: the Romanesque Fabric Malcolm Thurlby*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 125 (1995), 793-812 Jedburgh Abbey church: the Romanesque fabric Malcolm Thurlby* ABSTRACT The choir of the former Augustinian abbey church at Jedburgh has often been discussed with specific reference to the giant cylindrical columns that rise through the main arcade to support the gallery arches. This adaptation Vitruvianthe of giant order, frequently associated with Romsey Abbey, hereis linked with King Henry foundationI's of Reading Abbey. unusualThe designthe of crossing piers at Jedburgh may also have been inspired by Reading. Plans for a six-part rib vault over the choir, and other aspects of Romanesque Jedburgh, are discussed in association with Lindisfarne Priory, Lastingham Priory, Durham Cathedral MagnusSt and Cathedral, Kirkwall. The scale church ofthe alliedis with King David foundationI's Dunfermlineat seenis rivalto and the Augustinian Cathedral-Priory at Carlisle. formee e choith f Th o rr Augustinian abbey churc t Jedburgha s oftehha n been discussee th n di literature on Romanesque architecture with specific reference to the giant cylindrical columns that rise through the main arcade to support the gallery arches (illus I).1 This adaptation of the Vitruvian giant order is most frequently associated with Romsey Abbey.2 However, this association s problematicai than i e gianl th t t cylindrical pie t Romsea r e th s use yi f o d firse y onlth ba t n yi nave, and almost certainly post-dates Jedburgh. If this is indeed the case then an alternative model for the Jedburgh giant order should be sought. Recently two candidates have been put forward. -

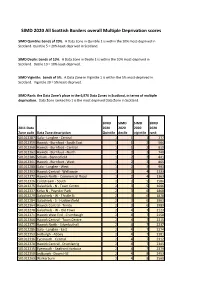

SIMD 2020 All Scottish Borders Overall Multiple Deprivation Scores

SIMD 2020 All Scottish Borders overall Multiple Deprivation scores SIMD Quintile: bands of 20%. A Data Zone in Quintile 1 is within the 20% most-deprived in Scotland. Quintile 5 = 20% least-deprived in Scotland. SIMD Decile: bands of 10%. A Data Zone in Decile 1 is within the 10% most-deprived in Scotland. Decile 10 = 10% least-deprived. SIMD Vigintile: bands of 5%. A Data Zone in Vigintile 1 is within the 5% most-deprived in Scotland. Vigintile 20 = 5% least-deprived. SIMD Rank: the Data Zone's place in the 6,976 Data Zones in Scotland, in terms of multiple deprivation. Data Zone ranked No 1 is the most deprived Data Zone in Scotland. SIMD SIMD SIMD SIMD 2011 Data 2020 2020 2020 2020 Zone code Data Zone description Quintile decile vigintile rank S01012287 Gala - Langlee - Central 1 1 1 277 S01012359 Hawick - Burnfoot - South East 1 1 2 564 S01012360 Hawick - Burnfoot - Central 1 1 2 619 S01012362 Hawick - Burnfoot - North 1 2 3 740 S01012386 Selkirk - Bannerfield 1 2 3 841 S01012361 Hawick - Burnfoot - West 1 2 3 865 S01012288 Gala - Langlee - West 1 2 3 993 S01012363 Hawick Central - Wellogate 1 2 4 1233 S01012372 Hawick North - Commercial Road 1 2 4 1363 S01012326 Coldstream - South 2 3 5 1586 S01012275 Galashiels - N - Town Centre 2 3 5 1696 S01012337 Kelso N - Poynder Park 2 3 6 1868 S01012279 Galashiels - W - Thistle St 2 3 6 1878 S01012284 Galashiels - S - Huddersfield 2 3 6 1963 S01012364 Hawick Central - Trinity 2 3 6 1989 S01012278 Galashiels - W - Old Town 2 4 7 2123 S01012371 Hawick West End - Crumhaugh 2 4 7 2158 S01012366