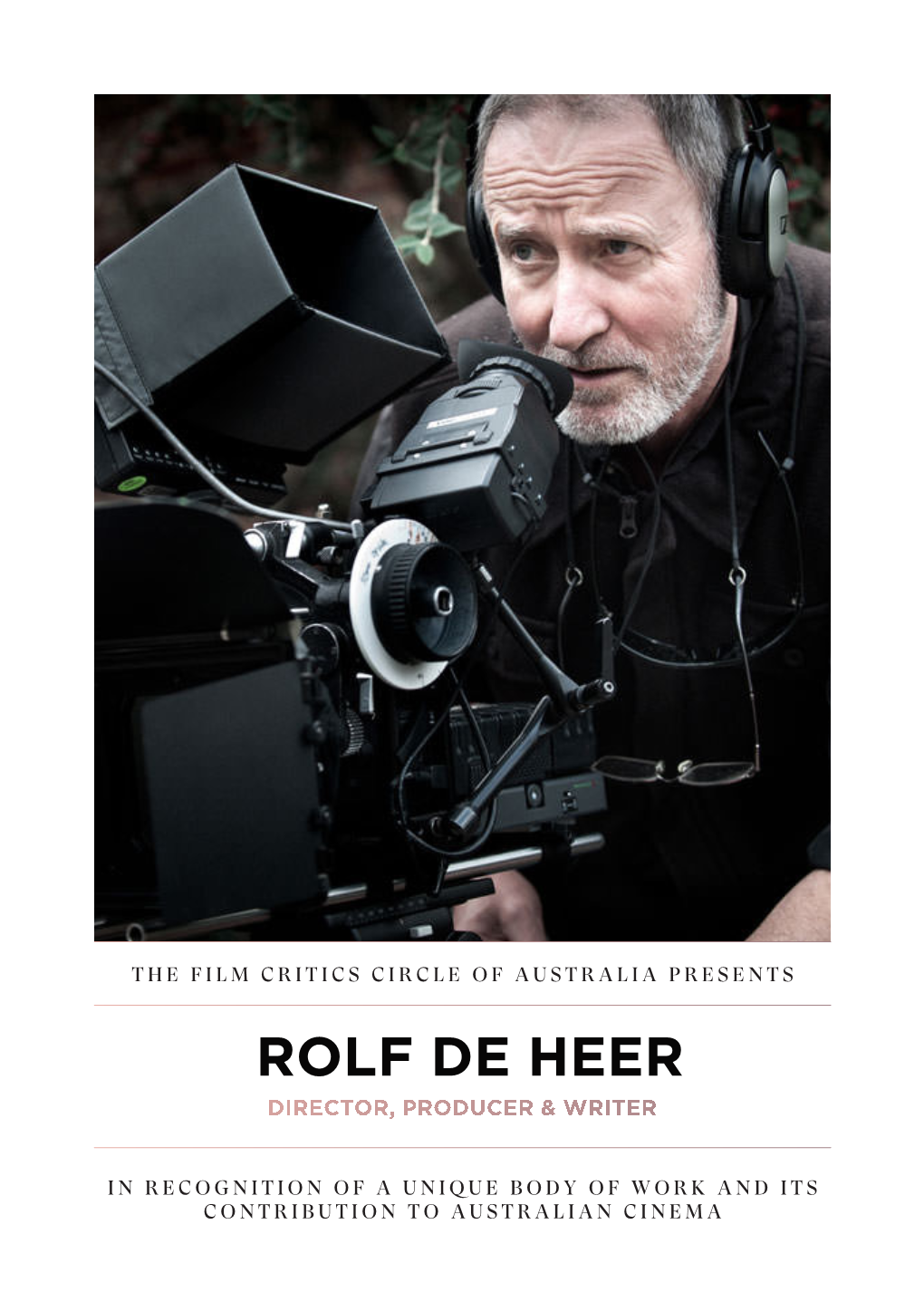

Rolf De Heer Director, Producer & Writer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download the BALANDA and the BARK CANOES

The Balanda and the Bark Canoes A documentary about making Ten Canoes May, 2005 Central Arnhem Land, Australia ‘We are making a movie. The story is their story, those that live on this land, in their language, and set a long time before the coming of the Balanda, as we white people are known. For the people of the Arafura Swamp, this film is an opportunity, maybe a last chance to hold on to the old ways. For all of us, the challenges are unexpected, the task beyond anything imagined. For me, it is the most difficult film I have made, in the most foreign land I've been to...and it is Australia.’ – Rolf de Heer Directors’ Q & A Q: What was the inspiration behind this documentary? And/or how did it come about? The documentary is a companion to the feature film Ten Canoes. Ten Canoes is an in-language indigenous tragi-comedy set in the historical (pre-white settlement) and mythical past of the Ganalbingu (Yolngu) people. It is a cautionary tale of love, lust and revenge gone wrong. Although financed, the film spent three years in the development phase. There were a number of reasons why but one of them included consolidating the early rapport and trust between Rolf, his team and the community. During this time, Rolf began visiting the communities regularly and would return with new sets of working challenges and with stories full of adventure. It became apparent that a compelling documentary could be made in its own right. Rolf approached SBS Independent, investors in the feature film Ten Canoes, about documenting the already crazy yet exhilarating journey. -

Rolf De Heer

Rolf de Heer Film handler om sproget, barnet og den fremmede for Rolf de Heer, hvis hovedværk er den kulsorte komedie Bad Boy Bubby, og få andre instruktører har fokuseret så vedholdende på sproget som den hollandsk fødte australske instruktør Sproget er fundamentalt for enhver kom gentage, hvad andre siger. Hans eksperi munikation mellem mennesker, men det menter med åndedrætssystemet er hidtil er ikke nok i Rolf de Heers (f. 1951) film, gået ud over Kat, Flo og Pop og har givet hvor sproget både er fundament og alt, så ham tilnavnet The Cling Wrap Killer, hvil når Rolf de Heers film kredser om spro ket bringer ham i fængsel og senere igen get, siger de ikke bare noget om forholdet ud til en virkelighed, der ikke har plads til mellem mennesker eller om sproget i sig personer som Bubby. I stedet tager han til selv. Opmærksomheden kastes naturligt bage til barndomshjemmet, hvor han slår tilbage på filmens eget sprog. Bubby ihjel og forvandler sig til Pop. Rolf de Heers optagethed af sproget Udrustet med en ny identitet og et større føres i to retninger. Mod på den ene side erfaringsgrundlag drager han påny ud for uskylden og det barnlige og på den anden at erobre verden og blive et rigtigt menne side outsiderens perspektiv. I begge ret ske. ninger handler det om at se på det vante I virkeligheden er den 30-årige Bubby et udefra med friske øjne. barn, der for første gang skal opleve ver den uden sin mor og måske mere fatalt Den barnlige uskyld. 1 hovedværket Bad uden et sprog. -

David Gulpilil, AM

David Gulpilil, AM Born 1953, Gulparil, near Ramingining, Northern Territory. Lives Darwin, N.T. David Gulpilil’s full name is David Gulpilil Ridjimiraril Dalaithngu. Gulpilil is also spelt Gulparil, which is the name of his Country near Ramingining, central Arnhem Land, N.T. When, as a seventeen year-old, David Gulpilil lit up the cinema screen in the film, Walkabout, he did more than play a role. The performance was so strong, so imbued with a new type of graceful naturalism, that it re-defined perceptions of Aboriginality, especially in the field of screen acting. Over the next decade, David became the iconic Aboriginal actor of his generation, paving the way in the resurgence of the Australian film industry for more parts to be written for Aboriginal people, for more Aboriginal stories to be told. His charismatic, engaging and unforgettable performances in films like Storm Boy (1976, dir. Henri Safran), The Last Wave (1977, dir. Peter Weir) and Crocodile Dundee (1986, dir. Peter Faiman) helped bring Aboriginality into the mainstream of the screen arts. In his later work, including Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002, dir. Philip Noyce), The Tracker (2002, dir. Rolf de Heer), Australia (2008, dir. Baz Luhrmann) and the soon to be released Charlie's Country (2013, dir. Rolf de Heer), Gulpilil has brought tremendous dignity to the depiction of what it is to be Aboriginal. Through his art he has brought an incalculable amount of self-esteem to his community. Since the early 1970s, Gulpilil has earned more than 30 film credits, and performed alongside Dennis Hopper, Jack Thompson, Miles Davis, Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman, Kenneth Branagh, William Hurt, Richard Chamberlain, Guy Pearce, Paul Hogan, and Ernie Dingo, under acclaimed directors such as Peter Weir, Baz Lurhman, Philip Noyce, Wim Wenders and Rolf de Heer. -

David Stratton's Stories of Australian Cinema

David Stratton’s Stories of Australian Cinema With thanks to the extraordinary filmmakers and actors who make these films possible. Presenter DAVID STRATTON Writer & Director SALLY AITKEN Producers JO-ANNE McGOWAN JENNIFER PEEDOM Executive Producer MANDY CHANG Director of Photography KEVIN SCOTT Editors ADRIAN ROSTIROLLA MARK MIDDIS KARIN STEININGER HILARY BALMOND Sound Design LIAM EGAN Composer CAITLIN YEO Line Producer JODI MADDOCKS Head of Arts MANDY CHANG Series Producer CLAUDE GONZALES Development Research & Writing ALEX BARRY Legals STEPHEN BOYLE SOPHIE GODDARD SC SALLY McCAUSLAND Production Manager JODIE PASSMORE Production Co-ordinator KATIE AMOS Researchers RACHEL ROBINSON CAMERON MANION Interview & Post Transcripts JESSICA IMMER Sound Recordists DAN MIAU LEO SULLIVAN DANE CODY NICK BATTERHAM Additional Photography JUDD OVERTON JUSTINE KERRIGAN STEPHEN STANDEN ASHLEIGH CARTER ROBB SHAW-VELZEN Drone Operators NICK ROBINSON JONATHAN HARDING Camera Assistants GERARD MAHER ROB TENCH MARK COLLINS DREW ENGLISH JOSHUA DANG SIMON WILLIAMS NICHOLAS EVERETT ANTHONY RILOCAPRO LUKE WHITMORE Hair & Makeup FERN MADDEN DIANE DUSTING NATALIE VINCETICH BELINDA MOORE Post Producers ALEX BARRY LISA MATTHEWS Assistant Editors WAYNE C BLAIR ANNIE ZHANG Archive Consultant MIRIAM KENTER Graphics Designer THE KINGDOM OF LUDD Production Accountant LEAH HALL Stills Photographers PETER ADAMS JAMIE BILLING MARIA BOYADGIS RAYMOND MAHER MARK ROGERS PETER TARASUIK Post Production Facility DEFINITION FILMS SYDNEY Head of Post Production DAVID GROSS Online Editor -

TAJEMNICA ALEKSANDRY Pressbook

Tajemnica Aleksandry (Alexandra’s Project) RE ŻYSERIA ROLF DE HEER W KINACH OD 23 STYCZNIA 2004 DYSTRYBUCJA W POLSCE ul. Zamenhofa 1, 00-153 Warszawa tel.: (+4822) 536 92 00, fax: (+4822) 635 20 01 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.gutekfilm.pl re żyseria Rolf de Heer scenariusz Rolf de Heer zdj ęcia Ian Jones muzyka Graham Tardif monta ż Tania Nehme dźwi ęk James Currie scenografia Ian Jobson Phil MacPherson kostiumy Beverley Freeman wyst ępuj ą Gary Sweet Steve Helen Buday Aleksandra Bogdan Koca Bill Samantha Knigge Emma Jack Christie Sam Eillen Darley Christine Geoff Revell Rodney producenci Julie Ryan Dominco Procacci Rolf de Heer film wyprodukowany przez Fandango Australia Palace Films Hendon Studios South Australian Film Corporation Vertigo Productions Pty. Ltd. Australian Film Commission nagrody Montréal World Film Festival 2003 – Golden Zenith za najlepszy film z Oceanii Australia rok produkcji: 2003 czas trwania: 103 minuty kolor – Dolby Digital – 1:1,85 Tajemnica Aleksandry to thriller psychologiczo-erotyczny, opowiadaj ący w przewrotny sposób o instytucji mał żeństwa i odwiecznej wojnie płci. Dzi ęki klaustrofobicznym uj ęciom, niepokoj ącej ście żce d źwi ękowej oraz realistycznej grze aktorów, de Heerowi udało si ę uzyska ć nastrój znany z ostatnich filmów Davida Lyncha. Światowa premiera Tajemnicy Aleksandry miała miejsce w konkursie festiwalu filmowego w Berlinie w 2003. Film radykalnie podzielił publiczno ść i sprowokował burzliw ą dyskusj ę na temat współczesnego mał żeństwa, a tak że relacji mi ędzy męż czyzn ą i kobiet ą. Urodziny Steve’a (Gary Sweet), przeci ętnego czterdziestolatka zajmuj ącego kierownicze stanowisko w wielkiej korporacji, zapowiadaj ą si ę wyj ątkowo. -

Sound in the Films of Rolf De Heer

AURAL AUTEUR: SOUND IN THE FILMS OF ROLF DE HEER. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Published Papers in the Creative Industries Faculty at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, Australia. Supervisors: Ms. Helen Yeates Lecturer, Film and TV, Creative Industries Faculty, QUT. Dr. Vivienne Muller Lecturer, Creative Writing and Literary Studies, Creative Industries Faculty, QUT. Associate Professor Geoff Portmann Discipline Leader, Film and TV, Creative Industries Faculty, QUT. Written and submitted by David Bruno Starrs BSc (ANU), PGDipHlthSc (Curtin), BTh (Hons) (JCU), MFTV (Bond), MCA (Melb). Self-archived publications available at: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/view/person/Starrs,_D._Bruno.html January 2009. Aural Auteur: Sound in the Films of Rolf de Heer. 2 Aural Auteur: Sound in the Films of Rolf de Heer. ABSTRACT. Aural Auteur: Sound in the Films of Rolf de Heer. An interpretative methodology for understanding meaning in cinema since the 1950s, auteur analysis is an approach to film studies in which an individual, usually the director, is studied as the author of her or his films. The principal argument of this thesis is that proponents of auteurism have privileged examination of the visual components in a film-maker’s body of work, neglecting the potentially significant role played by sound. The thesis seeks to address this problematic imbalance by interrogating the creative use of sound in the films written and directed by Rolf de Heer, asking the question, “Does his use of sound make Rolf de Heer an aural auteur?” In so far as the term ‘aural’ encompasses everything in the film that is heard by the audience, the analysis seeks to discover if de Heer has, as Peter Wollen suggests of the auteur and her or his directing of the visual components (1968, 1972 and 1998), unconsciously left a detectable aural signature on his films. -

Ricerca Film Per Tematica

RICERCA FILM PER TEMATICA 10/2019 TEMATICA TITOLO E COLLOCAZIONE ADOLESCENZA • A tutta velocità – 710. • Amarcord – 564. • Anche libero va bene – 827. • Caterina va in città – 532. • Cielo d’ottobre – 787. • Coach Carter - 1619 • Corpo celeste – 1469. • Così fan tutti – 535. • Cuore selvaggio – 755. • L’albero di Natale – 183. • Detachment, Il distacco – 1554. • Diciassette anni –1261 – 1344. • Edward mani di forbice – 559. • Elephant – 449. • Emporte moi – 943. • Fidati – 197. • Flashdance – 376. • Fratelli d’Italia – 1467. • Fuga dalla scuola media – 107. • Gente comune – 237 – 287 – 446. • Harold e Maude – 399. • Il calamaro e la balena – 981. • Il club degli imperatori – 503 – 1030. • Il diario di Anna Frank – 292 – 528. • Il figlio – 275 – 345 – 840. • Il ladro di bambini – 68 – 152 – 847. • Il laureato – 150. • Il lungo giorno finisce – 57. • Il ribelle – 452 – 641. • Il ritorno – 378. • Il segreto di Esma – 949. • Il sogno di Calvin – 738. • Io ballo da sola – 227 – 450. • J’ai tué ma mère – 1753 - 1765. • Juno – 1303. • Kids – 123. • L’attimo fuggente – 35 – 35a – 269 – 683. • L’India raccontata da James Ivory – 696. • L’occhio del diavolo – 515 – 581. • L’ospite d’inverno – 101 – 102 – 119. • La città dei ragazzi – 308 – 1465. • La classe – 1229 – 1370. • La luna – 804. • La scuola – 55 – 524. • La zona - 1476 • Le ricamatrici – 658. • Lolita – 138. • Luna nera – 708. • Maddalena… zero in condotta – 499 – 1470. • Making off – 1283. • MarPiccolo – 1466. • Mask – 851. • Mean creek – 1126. • Mignon è partita – 597 – 665. • Munyurangabo – 1276. • Niente velo per Jasira – 1358. • No’I Albinoi – 649. • Noi i ragazzi delle zoo di Berlino – 569 – 958. • Non è giusto – 281. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

QUT Digital Repository

QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Starrs, D. Bruno (2007) Sounds of silence: an interview with Rolf de Heer. Metro Magazine(152):pp. 18-21. © Copyright 2007 D. Bruno Starrs Sounds of Silence: An Interview with Rolf de Heer. By D. Bruno Starrs. Rolf de Heer’s twelfth feature film, “Dr. Plonk” (starring Nigel Lunghi, Paul Blackwell and Magda Szubanski), premiered on closing night of the 2007 Adelaide Film Festival recently. Already feted as South Australian of the Year, De Heer received the Don Dunstan award on opening night to rapturous applause from his home town crowd. D. Bruno Starrs interviewed Australia’s most successful non- mainstream film-maker about the black and white, silent slap-stick comedy three days before its inaugural screening. D. Bruno Starrs: With “Dr. Plonk” you’ve made an ostensibly silent film. Do you think audiences don’t care about sound? Rolf de Heer: They care enormously about sound. Sound is, from my point of view, 60% of the emotional content of a film. So they do, enormously. Why, then, have you made a silent film? (Laughing) Because I thought I’d enjoy doing so. Look, it’s a funny one, and it’s not what I expected to do … In fact, I hit upon it at the time James Currie and I had just finished the “Ten Canoes” mix and, literally, just about to have a drink to celebrate and that’s when I discovered that I would be doing a silent film. And I said, “Sorry, Jim, you’re not working on the next one”. -

EDAV (Educazione Audiovisiva) Sussidio Mensile Di «Lettura» Dei Media E D’Uso Dei Loro Linguaggi Fondato Da NAZARENO TADDEI S.J

EDAV (Educazione Audiovisiva) sussidio mensile di «lettura» dei media e d’uso dei loro linguaggi fondato da NAZARENO TADDEI S.J. diretto dal luglio 2006 da Andrea Fagioli edito dal CiSCS Centro internazionale dello Spettacolo e della Comunicazione Sociale - Roma (*) Indice di indici di 37 anni dal 1972-73 al 2009 a cura di Bruno Michelon INDICE ...ARGUTA PUBBLICITÀ..., [figura], n. 85, p. 1 ...FIORI... di NaT, [foto di copertina], n. 216, p. 1-2 ...LASSA STAR I SANTI, (pubblicità che crea mentalità), [vetrinetta dei media (a cura di Nazareno Taddei S.J.) – pubblicità], n. 296, p. 18 ?BERLUSCONI? di NaT, [foto di copertina], n. 223, p. 1-2 «...ED È ANCORA AMORE» (DA UN CALENDARIO DI GIANNI BELLESIA) di Achille Abramo Saporiti, [foto di copertina – lettura foto], n. 326, pp. 1-2 «‖IN ALTUM‖ LEGGENDO I FILM» di Nazareno Taddei S.J., [studio]: 1. LA SITUAZIONE: MA PERCHÉ?, n. 286, pag. 2 2. USCIRE DALLA NEBBIA, n. 287, pag. 6 3. ANCORA DELLA MENTALITÀ… E NON SOLO, n. 288, pag. 3 4. «NUOVI MODI DI COMUNICARE», n. 289-90, pag. 3 5. LA «LETTURA (STRUTTURALE)» È UNA POSSIBILE SOLUZIONE, n. 291, p. 3 6. «LEGGERE FILM PER FORMARE LA PERSONA»: 1° L‘ASPETTO TEORICO, n. 292, p. 3 Appendice: a) I FILM CHE PIACEVANO A LUCIANO TAGLIAVINI di Eugenio Bicocchi, [studio], n. 292, p. 7 b) THELMA E LOUISE di Ridley Scott (n. 1937), (Olinto Brugnoli), [lettura – film], n. 292, p. 8 7. «LEGGERE FILM PER FORMARE LA PERSONA: 2° L‘ASPETTO METODOLOGICO», n. 294, p. 7 8. «LEGGERE FILM PER FORMARE LA PERSONA: APPENDICE», n. -

Wadu Matyidi

WADU MATYIDI Press Kit Enquiries: Marjo Stroud Mob: 0432 504 037 [email protected] Sonja Vivienne Mob: 0418 660 908 [email protected] 0 Contents Audience Blurbs and Synopsis 2 Behind the Scenes (documentaries) 3 Location 5 Production Overview 6 Adnyamathanha Ngawarla Glossary 8 Production Team 9 Visual References 12 1 General Audience Blurb – Wadu Matyidi (War-do Mudgee-dee) breaks new ground in Indigenous animation. This eight minute dramatization brings the past to life through the imagination of a talented Adnyamathanha language revival class. It is accompanied by back-story documentaries featuring students of the class and their community. Child Audience Blurb – Imagine it! Non-stop fun and games with cheeky little brother in a totally awesome, adult-free, adventure playground. Throw in some supernatural creature possibilities, well-timed burps and farts and some seriously bad weather and anything could happen! Synopsis Wadu Matyidi – A Time Long Gone In this short animated film we’re taken back to pre-contact times (early 1800s) when Adnyamathanha children of the Flinders Ranges were inspired, schooled and entertained by their interactions with ‘country’. The characters in the story are three adventurous Adnyamathanha kids who set out for a day of exploration near their camp. The children play traditional games and spook one another with tales of the ancient creatures of their country. They see unusual tracks that set their hearts and imaginations racing. Then, unexpectedly they make a discovery that changes their lives forever. Unlike many animations with an Aboriginal theme, Wadu Matyidi diverges from Dreaming story traditions. Almost like an ancestral memory, this story set two hundred years in the past has arisen from the imaginations of students attending an Adnyamathanha Ngawarla (language) class from 2008 to 2010. -

Annual Report 2009-10

New Zealand Film Commission Annual Report 2010 G19 Report of the New Zealand Film Commission for the year ended 30 June 2010 In accordance with Sections 150 to 157 of the Crown Entities Act 2004, on behalf of the New Zealand Film Commission we present the Annual Report covering the activities of the NZFC for the 12 months ended 30 June, 2010. Patsy Reddy Andrew Cornwell Chair Board Member PO Box 11-546 Wellington www.nzfilm.co.nz Funded by the New Zealand Government through the Ministry for Culture and Heritage and by the Lottery Grants Board Highlights The NZFC committed production financing to nine new feature films and eight short films during the financial year. It also supported the completion of 16 digital features. The NZFC provided strategic, logistical and financial support in the form of prints and advertising grants for seven new NZ features released in New Zealand cinemas during the year. Taika Waititi’s Contents feature filmBoy premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. It was awarded the Grand Prix award in the Generation Section of the Berlin Film Festival in February 2010 and went on to become the highest grossing NZ film of all time with a box office of more than $9 million. Gaylene Preston’s filmHome By Christmas enjoyed a highly successful cinematic release reaching $1.15 million box office. The film was nominated for 10 Qantas Film Awards. Independently financed feature documentaryThis Way of Life, directed by Tom Burstyn and produced by Sumner Burstyn, received a Special Mention in the Generation Section at the Berlin Film Festival.