Ethics and Aesthetics in Contemporary Basque Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who in Basque Music Today

Who’s Who in Basque music today AKATZ.- Ska and reggae folk group Ganbara. recorded in 2000 at the circles. In 1998 the band DJ AXULAR.- Gipuzkoa- Epelde), accomplished big band from Bizkaia with Accompanies performers Azkoitia slaughterhouse, began spreading power pop born Axular Arizmendi accordionist associated a decade of Jamaican like Benito Lertxundi, includes six of their own fever throughout Euskadi adapts the txalaparta to invariably with local inspiration. Amaia Zubiría and Kepa songs performed live with its gifted musicians, techno music. In his second processions, and Angel Junkera, in live between 1998 and 2000. solid imaginative guitar and most recent CD he also Larrañaga, old-school ALBOKA.-Folk group that performances and on playing and elegant adds voices from the bertsolari and singer who has taken its music beyond record. In 2003 he recorded melodies. Mutriku children's choir so brilliantly combines our borders, participating a CD called "Melodías de into the mix, with traditional sensibilities and in festivals across Europe. piel." CAMPING GAZ & DIGI contributions by Mikel humor, are up to their ears Instruments include RANDOM.- Comprised of Laboa. in a beautiful, solid and alboka, accordion and the ANJE DUHALDE.- Singer- Javi Pez and Txarly Brown enriching project. Their txisu. songwriter who composes from Catalonia, the two DOCTOR DESEO.- Pop rock fresh style sets them apart. in Euskara. Former member joined forces in 1995, and band from Bilbao. They are believable, simple, ALEX UBAGO.-Donostia- of late 70s folk-rock group, have since played on and Ringleader Francis Díez authentic and, most born pop singer and Errobi, and of Akelarre. -

The Case of Eta

Cátedra de Economía del Terrorismo UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales DISMANTLING TERRORIST ’S ECONOMICS : THE CASE OF ETA MIKEL BUESA* and THOMAS BAUMERT** *Professor at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid. **Professor at the Catholic University of Valencia Documento de Trabajo, nº 11 – Enero, 2012 ABSTRACT This article aims to analyze the sources of terrorist financing for the case of the Basque terrorist organization ETA. It takes into account the network of entities that, under the leadership and oversight of ETA, have developed the political, economic, cultural, support and propaganda agenda of their terrorist project. The study focuses in particular on the periods 1993-2002 and 2003-2010, in order to observe the changes in the financing of terrorism after the outlawing of Batasuna , ETA's political wing. The results show the significant role of public subsidies in finance the terrorist network. It also proves that the outlawing of Batasuna caused a major change in that funding, especially due to the difficulty that since 2002, the ETA related organizations had to confront to obtain subsidies from the Basque Government and other public authorities. Keywords: Financing of terrorism. ETA. Basque Country. Spain. DESARMANDO LA ECONOMÍA DEL TERRORISMO: EL CASO DE ETA RESUMEN Este artículo tiene por objeto el análisis de las fuentes de financiación del terrorismo a partir del caso de la organización terrorista vasca ETA. Para ello se tiene en cuenta la red de entidades que, bajo el liderazgo y la supervisión de ETA, desarrollan las actividades políticas, económicas, culturales, de propaganda y asistenciales en las que se materializa el proyecto terrorista. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

A Comparative Study of Extremism Within Nationalist Movements

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXTREMISM WITHIN NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND SPAIN by Ashton Croft Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of History Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas 22 April 2019 Croft 1 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXTREMISM WITHIN NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND SPAIN Project Approved: Supervising Professor: William Meier, Ph.D. Department of History Jodi Campbell, Ph.D. Department of History Eric Cox, Ph.D. Department of Political Science Croft 2 ABSTRACT Nationalism in nations without statehood is common throughout history, although what nationalism leads to differs. In the cases of the United Kingdom and Spain, these effects ranged in various forms from extremism to cultural movements. In this paper, I will examine the effects of extremists within the nationalism movement and their overall effects on societies and the imagined communities within the respective states. I will also compare the actions of extremist factions, such as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA), and the Scottish National Liberation Army (SNLA), and examine what strategies worked for the various nationalist movements at what points, as well as how the movements connected their motives and actions to historical memory. Many of the groups appealed to a wider “imagined community” based on constructing a shared history of nationhood. For example, violence was most effective when it directly targeted oppressors, but it did not work when civilians were harmed. Additionally, organizations that tied rhetoric and acts back to actual histories of oppression or of autonomy tended to garner more widespread support than others. -

Boletín BIBLIUGM Noviembre 2017

1 Boletín BIBLIUGM noviembre 2017 En el siguiente listado aparecen las últimas incorporaciones al fondo de la Biblioteca del Instituto Universitario «General Gutiérrez Mellado» en el mes de noviembre de 2017. En el listado no se incluyen nuevas adquisiciones ni fondos procedentes de la Biblioteca Central. Se pueden consultar con más detalle en el catálogo http://biblio15.uned.es/ o en la propia biblioteca del IUGM. 1. Adolfo Suárez, la soledad del gladiador / Carlos Asorey Brey. [Madrid] : Lacre, 2016. Materias: Suárez, Adolfo (1932-2014), Biografías, España. 2. Apuntes hacia un nuevo modelo policial : Er.N.E., jornadas celebradas en el Palacio Euskalduna de Bilbao los días 24 y 25 de abril de 2013. [Vitoria-Gasteiz] : Ertzainen Nazional Elkartasuna = Sindicato Independiente de la Policía Vasca, 2013. Materias: Policía, País Vasco. 3. Con las víctimas del terrorismo / Antonio Duplá y Javier Villanueva (coords.). [San Sebastián] : Tercera Prensa = Hirugarren Prentsa, D.L. 2009. Materias: ETA, Víctimas del terrorismo, País Vasco, España. 4. La Coordinación de elementos militares, policiales y judiciales en las misiones de reconstrucción de los Estados. [Madrid] : Ministerio de Defensa, Secretaría General Técnica, 2017. Materias: Unión Europea, Naciones Unidas, Reconstrucción posbélica, Mantenimiento de la paz, Misiones no militares, Sahel. 5. El Crimen organizado en América Latina : manifestaciones, facilitadores y reacciones / compiladoras, Carolina Sampó, Valeska Troncoso ; [autores, Alda Mejías, Sonia ... et. al.]. Madrid : Instituto Universitario General Gutiérrez Mellado - UNED, 2017. Materias: Crimen organizado, Drogas, Violencia, Política gubernamental, América Latina. 6. Democracia, nacionalismo y terrorismo en el País Vasco / [autor, Ciudadanía y Libertad ; prólogo, Florencio Domínguez Iribarren]. 2 Vitoria-Gasteiz : Ciudadanía y Libertad, 2010. -

Dur 04/06/2017

DOMINGO 4 DE JUNIO DE 2017 4 NACIONAL EN CORTO PANCRACIO LUCHA LIBRE Tamaulipas sobresale en gimnasia rítmica de ON 2017 La representación de Tamaulipas dominó y sobresalió en la gimnasia rítmica de la Olimpiada Nacional 2017, que se desarrolla en la “Sultana del Norte”. Norma Cobos, de apenas 10 años de edad, deslum- Revancha bró en las instalaciones del Gimnasio Nuevo León Gonzalitos, luego de colgarse cuatro medallas de oro gracias a su entusiasmo, gracia, calidad, armonía y belleza. Cobos Arteaga obtuvo el primer lugar por equi- entre gladiadores pos, en all around, aro y pelota, además consiguió dos metales más para ser la máxima ganadora de la com- petencia Sumó una plata en manos libres y un bron- EL UNIVERSAL ce en cuerda. CDMX El Último Guerrero siempre Montemayor y Alanís, final B en ha sido un hombre de retos Copa del Mundo de Canotaje y en varias ocasiones ha ma- nifestado su intención de ju- La dupla mexicana conformada por Maricela Montema- garse su cabellera contra yor y Karina Alanís disputarán la final B de la Copa del Atlantis quien hace tres Mundo de Canotaje, que se desarrolla en esta capital. años lo despojó de su tapa. En la modalidad de doble kayak distancia de 500 Sin embargo, en la histo- metros (K2-500) las canoístas tricolores ya no podrán ria de la lucha libre hay va- pelear medallas debido a que se colocaron en el quin- rios gladiadores que han per- to sitio dentro de la fase de semifinales, celebradas dido su capucha; luego por su este sábado. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface......................................................................................... -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

'Pot Trucks' May Be on the Move After New Year

+ PLUS >> Outrage at the VA, Opinion 4A. COMMUNITY LOCAL SPORTS Armed Training Top notch Forces the Trainer swim team a family on global returns for affair logistics ‘14 season See Page 8A See Page 5A See Page 1B THURSDAY, JULY 31, 2014 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM EUGENE JEFFERSON: Wife active in campaign for the upcom- voters in recent weeks, Horne on voter rolls, Florida statute Despite indictment, Betty Jefferson has ing primary, said, and the calls are perfectly requires an absentee ballot be helped voters request absentee ballots. Supervisor of legal. mailed to that address. Elections Liz “She calls and gets us on the Horne did not accuse Jefferson By ROBERT BRIDGES Horne said line for them,” Horne said. of wrongdoing. [email protected] alleged voter fraud involving Wednesday. The elections worker asks the “That’s the law,” she said. absentee ballots during the 2010 Betty Jefferson voter his or her name, address Jefferson and another E. Jefferson A city councilman’s wife, election, has been helping res- has been calling and date of birth. though under indictment for idents request absentee ballots Horne’s office on behalf of city If the answers match data CAMPAIGN continued on 7A Suddenly, Lake City a magnet for new business Eateries, more now looking to Tax holiday this weekend locate here. By SARAH LOFTUS | [email protected] By TONY BRITT Back to school [email protected] Ashton Hoy, like many Columbia County residents, plans to take advan- Signs of a growing tage of the back-to-school tax-free economy are sprouting weekend starting Friday. -

Control Biológico De Insectos: Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada Un Enfoque Agroecológico

Control biológico de insectos: Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada un enfoque agroecológico Control biológico de insectos: un enfoque agroecológico Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada Ciencia y Tecnología Editorial Universidad de Antioquia Ciencia y Tecnología © Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada © Editorial Universidad de Antioquia ISBN: 978-958-714-186-3 Primera edición: septiembre de 2008 Diseño de cubierta: Verónica Moreno Cardona Corrección de texto e indización: Miriam Velásquez Velásquez Elaboración de material gráfico: Ana Cecilia Galvis Martínez y Alejandro Henao Salazar Diagramación: Luz Elena Ochoa Vélez Coordinación editorial: Larissa Molano Osorio Impresión y terminación: Imprenta Universidad de Antioquia Impreso y hecho en Colombia / Printed and made in Colombia Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial, por cualquier medio o con cualquier propósito, sin autorización escrita de la Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. Editorial Universidad de Antioquia Teléfono: (574) 219 50 10. Telefax: (574) 219 50 12 E-mail: [email protected] Sitio web: http://www.editorialudea.com Apartado 1226. Medellín. Colombia Imprenta Universidad de Antioquia Teléfono: (574) 219 53 30. Telefax: (574) 219 53 31 El contenido de la obra corresponde al derecho de expresión del autor y no compromete el pensamiento institucional de la Universidad de Antioquia ni desata su responsabilidad frente a terceros. El autor asume la responsabilidad por los derechos de autor y conexos contenidos en la obra, así como por la eventual información sensible publicada en ella. Nicholls Estrada, Clara Inés Control biológico de insectos : un enfoque agroecológico / Clara Inés Nicholls Estrada. -- Medellín : Editorial Universidad de Antioquia, 2008. 282 p. ; 24 cm. -- (Colección ciencia y tecnología) Incluye glosario. Incluye bibliografía e índices. -

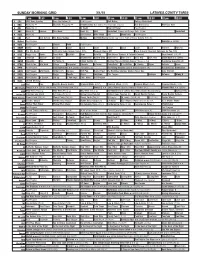

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.