Democracy in the Shadow of the Deep State Guardian Hybrid Regimes in Turkey and Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

ISI in Pakistan's Domestic Politics

ISI in Pakistan’s Domestic Politics: An Assessment Jyoti M. Pathania D WA LAN RFA OR RE F S E T Abstract R U T D The articleN showcases a larger-than-life image of Pakistan’s IntelligenceIE agencies Ehighlighting their role in the domestic politics of Pakistan,S C by understanding the Inter-Service Agencies (ISI), objectives and machinations as well as their domestic political role play. This is primarily carried out by subverting the political system through various means, with the larger aim of ensuring an unchallenged Army rule. In the present times, meddling, muddling and messing in, the domestic affairs of the Pakistani Government falls in their charter of duties, under the rubric of maintenance of national security. Its extra constitutional and extraordinary powers have undoubtedlyCLAWS made it the potent symbol of the ‘Deep State’. V IC ON TO ISI RY H V Introduction THROUG The incessant role of the Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, especially the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), in domestic politics is a well-known fact and it continues to increase day by day with regime after regime. An in- depth understanding of the subject entails studying the objectives and machinations, and their role play in the domestic politics. Dr. Jyoti M. Pathania is Senior Fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. She is also the Chairman of CLAWS Outreach Programme. 154 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2020 ISI IN PAKISTAN’S DOMESTIC POLITICS ISI is the main branch of the Intelligence agencies, charged with coordinating intelligence among the -

Turkey's Deep State

#1.12 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey FEATURE ARTICLES TURKEY’S DEEP STATE CULTURE INTERNATIONAL POLITICS ECOLOGY AKP’s Cultural Policy: Syria: The Case of the Seasonal Agricultural Arts and Censorship “Arab Spring” Workers in Turkey Pelin Başaran Transforming into the Sidar Çınar Page 28 “Arab Revolution” Page 32 Cengiz Çandar Page 35 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Content Editor’s note 3 ■ Feature articles: Turkey’s Deep State Tracing the Deep State, Ayşegül Sabuktay 4 The Deep State: Forms of Domination, Informal Institutions and Democracy, Mehtap Söyler 8 Ergenekon as an Illusion of Democratization, Ahmet Şık 12 Democratization, revanchism, or..., Aydın Engin 16 The Near Future of Turkey on the Axis of the AKP-Gülen Movement, Ruşen Çakır 18 Counter-Guerilla Becoming the State, the State Becoming the Counter-Guerilla, Ertuğrul Mavioğlu 22 Is the Ergenekon Case an Opportunity or a Handicap? Ali Koç 25 The Dink Murder and State Lies, Nedim Şener 28 ■ Culture Freedom of Expression in the Arts and the Current State of Censorship in Turkey, Pelin Başaran 31 ■ Ecology Solar Energy in Turkey: Challenges and Expectations, Ateş Uğurel 33 A Brief Evaluation of Seasonal Agricultural Workers in Turkey, Sidar Çınar 35 ■ International Politics Syria: The Case of the “Arab Spring” Transforming into the “Arab Revolution”, Cengiz Çandar 38 Turkey/Iran: A Critical Move in the Historical Competition, Mete Çubukçu 41 ■ Democracy 4+4+4: Turning the Education System Upside Down, Aytuğ Şaşmaz 43 “Health Transformation Program” and the 2012 Turkey Health Panorama, Mustafa Sütlaş 46 How Multi-Faceted are the Problems of Freedom of Opinion and Expression in Turkey?, Şanar Yurdatapan 48 Crimes against Humanity and Persistent Resistance against Cruel Policies, Nimet Tanrıkulu 49 ■ News from hbs 53 Heinrich Böll Stiftung – Turkey Representation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. -

Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011

Thai Netizen Network Annual Report: Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011 An annual report of Thai Netizen Network includes information, analysis, and statement of Thai Netizen Network on rights, freedom, participation in policy, and Thai internet culture in 2011. Researcher : Thaweeporn Kummetha Assistant researcher : Tewarit Maneechai and Nopphawhan Techasanee Consultant : Arthit Suriyawongkul Proofreader : Jiranan Hanthamrongwit Accounting : Pichate Yingkiattikun, Suppanat Toongkaburana Original Thai book : February 2012 first published English translation : August 2013 first published Publisher : Thai Netizen Network 672/50-52 Charoen Krung 28, Bangrak, Bangkok 10500 Thailand Thainetizen.org Sponsor : Heinrich Böll Foundation 75 Soi Sukhumvit 53 (Paidee-Madee) North Klongton, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand The editor would like to thank you the following individuals for information, advice, and help throughout the process: Wason Liwlompaisan, Arthit Suriyawongkul, Jiranan Hanthamrongwit, Yingcheep Atchanont, Pichate Yingkiattikun, Mutita Chuachang, Pravit Rojanaphruk, Isriya Paireepairit, and Jon Russell Comments and analysis in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect opinion of the Thai Netizen Network which will be stated clearly Table of Contents Glossary and Abbreviations 4 1. Freedom of Expression on the Internet 7 1.1 Cases involving the Computer Crime Act 7 1.2 Internet Censorship in Thailand 46 2. Internet Culture 59 2.1 People’s Use of Social Networks 59 in Political Movements 2.2 Politicians’ Use of Social -

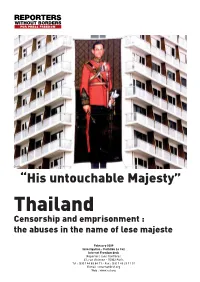

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

The Case of Said Nursi

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 The Dialectics of Secularism and Revivalism in Turkey: The Case of Said Nursi Zubeyir Nisanci Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Nisanci, Zubeyir, "The Dialectics of Secularism and Revivalism in Turkey: The Case of Said Nursi" (2015). Dissertations. 1482. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1482 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2015 Zubeyir Nisanci LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE DIALECTICS OF SECULARISM AND REVIVALISM IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF SAID NURSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN SOCIOLOGY BY ZUBEYIR NISANCI CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 Copyright by Zubeyir Nisanci, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful to Dr. Rhys H. Williams who chaired this dissertation project. His theoretical and methodological suggestions and advice guided me in formulating and writing this dissertation. It is because of his guidance that this study proved to be a very fruitful academic research and theoretical learning experience for myself. My gratitude also goes to the other members of the committee, Drs. Michael Agliardo, Laureen Langman and Marcia Hermansen for their suggestions and advice. -

27 Bangkok Indexit.Indd 339 12/15/11 11:00:18 AM 340 Index

Index 339 INDEX A amnesty, 279–83, 285, 301, 303 Abhisit Vejjajiva, 5, 7–8, 20, 25, 27, Amnuay Virawan, 17 30–31, 38–40, 43–45, 47, 72, Amsterdam, Robert, 280–81 77–80, 100, 120, 123–5, 132, 135, Anan Panyarachun, 44, 104, 169, 144, 165–66, 168, 173, 178, 182, 305–306 186, 194, 200–201, 245, 253, Ananda Mahidol, King, 73, 180 257–62, 274–76, 282–83, 285, 290, ancien régime, 287, 295 294, 298, 313, 319, 321, 323 Angkor Sentinel, military exercise, background of, 35 208 government under, 32–36, 42, 44, anti-monarchical conspiracy theory, 74, 76, 82, 102, 111, 115, 138, 74, 80 158, 169, 179, 183, 185, 195, see also “lom chao” 203, 205–207, 209–10, 267, 278, “anti-system” forces, 129 280, 305, 309, 329 anti-Thaksin media, 79 reform package proposed by, 89, 95 Anuman Ratchathon, Phraya, 2 absolute monarchy, 22, 192, 221–22, Anuphong Paochinda, 25, 33, 315 269–70 Apichatphong Weerasethakun, see also constitutional monarchy; 184–85 monarchy Appeals Court, 277 absolute poverty, 27, 156, 324 “aristocratic liberalism”, 105 Academy Fantasia, reality show, 93 Army, Thai, 21–22, 25, 35, 43–44, activist monks, 290–92 76–78, 87, 133, 139, 165, 220, agents provocateurs, 294, 299 224, 227, 293, 298, 302, 304, 307, agrarian change, waves of, 232–36 309–10, 323 “ai mong”, 78 psychological warfare unit, 237 Allende, Salvador, 50 restructured, 128 Amara Phongsaphit, 303 Arvizu, Alexander, 253 American Embassy, see U.S. Embassy ASEAN (Association of Southeast ammat (establishment), 21–22, 27, 29, Asian Nations), 166, 202, 204–205, 38, 93, 99, 135, 137–38, -

Media-Watch-On-Hate-Speech-May

Media Watch on Hate Speech & Discriminatory Language May - August 2013 Report Hrant Dink Foundation Halaskargazi Cad. Sebat Apt. No. 74 D. 1 Osmanbey-Şişli 34371 Istanbul/TURKEY Phone: 0212 240 33 61 Fax: 0212 240 33 94 E-mail: [email protected] www.nefretsoylemi.org www.hrantdink.org Media Watch on Hate Speech Project Coordinators Nuran Gelişli – Zeynep Arslan Part I : Monitoring Hate Speech in the National and Local Press in Turkey İdil Engindeniz Part II: Discriminatory Discourse in Print Media Gözde Aytemur Nüfuscu Translator Melisa Akan Contributors Berfin Azdal Rojdit Barak Azize Çay İbrahim Erdoğan Eda Güldağı Merve Nebioğlu Günce Keziban Orman (statistic data analysis) Nazire Türkoğlu Yunus Can Uygun Media Watch on Hate Speech Project is funded by Friedrich Naumann Foundation, Global Dialogue, the British Embassy and Danida. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders. CONTENTS MONITORING HATE SPEECH IN THE MEDIA 1 MONITORING HATE SPEECH IN THE NATIONAL AND LOCAL PRESS IN TURKEY 2 PART I: HATE SPEECH IN PRINT MEDIA 5 FINDINGS 6 NEWS ITEMS IDENTIFIED DURING THE PERIOD MAY-AUGUST 2013 16 EXAMPLES BY CATEGORY 24 1) ENMITY / WAR DISCOURSE Masons, communists and Jews! – Abdurrahman Dilipak 24 From EMPATHY to YOUPATHY! – Dursen Özalemdar 26 2) EXAGGERATION / ATTRIBUTION / DISTORTION German violence to the Turk – Dogan News Agency 28 ‘Do not be treacherous!’ - News Center 30 3) BLASPHEMY/ INSULT/ DENIGRATION Unwavering hatred and grudge - C. Turanlı 31 No such cowardice was ever seen before -

HC Dissertation Final

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ________________ Date A Muslim Humanist of the Ottoman Empire: Ismail Hakki Bursevi and His Doctrine of the Perfect Man By Hamilton Cook Doctor of Philosophy Islamic Civilizations Studies _________________________________________ Professor Vincent J. Cornell Advisor _________________________________________ Professor Ruby Lal Committee Member _________________________________________ Professor Devin J. Stewart Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date A Muslim Humanist of the Ottoman Empire: Ismail Hakki Bursevi and His Doctrine of the Perfect Man By Hamilton Cook M.A. Brandeis University, 2013 B.A., Brandeis University, 2012 Advisor: Vincent J. Cornell, Ph.D. -

Humour As Resistance a Brief Analysis of the Gezi Park Protest

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS 2 PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS David and Toktamış (eds.) In May and June of 2013, an encampment protesting against the privatisation of an historic public space in a commercially vibrant square of Istanbul began as a typical urban social movement for individual rights and freedoms, with no particular political affiliation. Thanks to the brutality of the police and the Turkish Prime Minister’s reactions, the mobilisation soon snowballed into mass opposition to the regime. This volume puts together an excellent collection of field research, qualitative and quantitative data, theoretical approaches and international comparative contributions in order to reveal the significance of the Gezi Protests in Turkish society and contemporary history. It uses a broad spectrum of disciplines, including Political Science, Anthropology, Sociology, Social Psychology, International Relations, and Political Economy. Isabel David is Assistant Professor at the School of Social and Political Sciences, Universidade de Lisboa (University of Lisbon) , Portugal. Her research focuses on Turkish politics, Turkey-EU relations and collective ‘Everywhere Taksim’ action. She is currently working on an article on AKP rule for the Journal of Contemporary European Studies. Kumru F. Toktamış, PhD, is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Depart- ment of Social Sciences and Cultural Studies of Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY. Her research focuses on State Formation, Nationalism, Ethnicity and Collective Action. In 2014, she published a book chapter on ‘Tribes and Democratization/De-Democratization in Libya’. Edited by Isabel David and Kumru F. Toktamış ‘Everywhere Taksim’ Sowing the Seeds for a New Turkey at Gezi ISBN: 978-90-8964-807-5 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 0 8 9 6 4 8 0 7 5 ‘Everywhere Taksim’ Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. -

Copenhagen School and Securitization of Cyberspace in Turkey

Propósitos y Representaciones Jan. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(1), e850 ISSN 2307-7999 Special Number: Educational practices and teacher training e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.850 RESEARCH ARTICLES Copenhagen school and securitization of cyberspace in Turkey Escuela de copenhague y titulización del ciberespacio en turquía Didem Aydindag University of Kyrenia, Turkey ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4752-5037 Received 08-12-20 Revised 09-30-20 Accepted 10-13-20 On line 01-12-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Aydindag, D. (2021). Copenhagen school and securitization of Email: [email protected] cyberspace in turkey. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9 (SPE1), e850. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.e850 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2021. This article is distributed under license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/) Copenhagen school and securitization of cyberspace in Turkey Summary With a particular rise since the turn of the millennium, cyber-security become one of the most important security sector in contemporary security politics. Despite this, the convergence of cyberspace and security has mostly been analyzed within the context of technical areas and had been neglected in the political realm and international relations academia. The article argues that in line with developments in the domestic and international arena, the AKP government shifted towards the securitization of cyberspace. Secondly the article argues that there seems to be two waves of securitization and desecuritization within the case. The first wave starts from 2006 through the end of 2017 whereby cyber securitization took place within the subunit level and very much connected to political and societal sectors. -

Biographies of Political Leaders of the Turkish Republic

Biographies of Political Leaders of the Turkish Republic RECEP TAYYIP ERDOĞAN Israeli President, has given him heroic status among the general Middle Eastern public. Recently, at the Council of Prime Minister of the Turkish Republic since 2003 Europe Parliamentary Assembly, Erdoğan responded, with strong and clearly critical remarks to the questions of European Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who is originally from Rize, a Black Sea parliamentarians about sensitive issues in Turkey, for example coastal city, was born on 26 February 1954 in Istanbul. In relations with Armenia, freedom of the press, and the ten 1965 he completed his primary education at the Kasımpaşa percent vote barrier. While Erdoğan’s rebukes tend to surprise Piyale Elementary School and, in 1973, graduated from the the international public, Turkish people are accustomed to his Istanbul Religious Vocational High School (İmam Hatip Lisesi). style. Moreover, many people believe that this belligerent style He also received a diploma from Eyüp High School since, at is the key to his success and popularity. the time, it was not possible for the graduates of religious vocational high schools to attend university. He eventually studied Business Administration at the Marmara University, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences (which was then known as Aksaray School of Economics and Commercial Complete version of the Biography of Recep Tayyip Sciences) and received his degree in 1981. Erdogan at: In his youth, Erdoğan played amateur football from 1969 www.cidob.org/es/documentacion/biografias_lideres_ to 1982 in local football clubs. This was also a socially and politicos/europa/turquia/recep_tayyip_erdogan politically active period in his life.