August 26, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in Paper and Models Mari Lending*

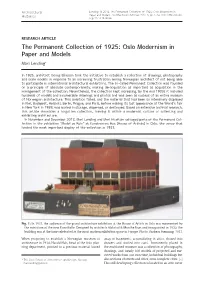

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Lending, M 2014 The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in +LVWRULHV Paper and Models. Architectural Histories, 2(1): 3, pp. 1-14, DOI: http://dx.doi. org/10.5334/ah.be RESEARCH ARTICLE The Permanent Collection of 1925: Oslo Modernism in Paper and Models Mari Lending* In 1925, architect Georg Eliassen took the initiative to establish a collection of drawings, photography and scale models in response to an increasing frustration among Norwegian architect of not being able to participate in international architectural exhibitions. The so-called Permanent Collection was founded on a principle of absolute contemporaneity, making de-acquisition as important as acquisition in the management of the collection. Nevertheless, the collection kept increasing. By the mid 1930s it included hundreds of models and innumerable drawings and photos and was seen as nucleus of an entire museum of Norwegian architecture. This ambition failed, and the material that had been so intensively displayed in Kiel, Budapest, Helsinki, Berlin, Prague, and Paris, before making its last appearance at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939, was buried in storage, dispersed, or destroyed. Based on extensive archival research, this article chronicles a forgotten collection, framing it within a modernist culture of collecting and exhibiting architecture. In November and December 2013, Mari Lending and Mari Hvattum salvaged parts of the Permanent Col- lection in the exhibition “Model as Ruin” at Kunstnernes Hus (House of Artists) in Oslo, the venue that hosted the most important display of the collection in 1931. Fig. 1: In 1931, the audience of the grand architecture exhibition at the House of Artists in Oslo was mesmerized by the miniature of the new Kunsthalle. -

Future Nordic Concrete Architecture

Future Nordic Concrete Architecture Future Nordic Concrete Architecture Introduction Through the 20th century concrete has become the most used building material in the world. The usage of concrete has led to a new architecture which exploits the isotopic properties of concrete to generate new shapes. Despite the considerable amount of concrete used in architecture, the concrete is surprisingly little visible. Often concrete is only used as the material for the load‐bearing structures and afterwards hidden behind other facade‐materials. But concrete has a big unexploited potential in order to create beautiful shapes with spectacular textures on the surface. This potential has been explored through a number of buildings which can be characterized as concrete architecture. In this context concrete architecture is defined as: - Architecture where concrete is used as a dominating and visible material and/or - Architecture where concrete is expressed through the geometry. In the following, a number of projects characterized as Nordic concrete architecture is presented together with a description of the epochs of the history of concrete architecture to which they belong. Nordic Concrete Architecture In Scandinavia, conditions different from the most other places in the world prevail. The Nordic climate causes significant changing weather conditions during the 4 seasons. This results in significant fewer hours with sun. Add to this that the sun stands low in the sky – especially in the winter season. This condition has had great influence on the architecture combined with the cultural development in Scandinavia. The style of building has always been inspired of the neighbours in the south – but always with a local interpretation and the usage of local building materials. -

Generelt Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Rjukan

Områdevis beskrivelse Generelt Innholdsfortegnelse 1 Rjukan .............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Rjukan – bakgrunn, framvekst og særpreg ............................................................................. 2 1.2 Byformingsidealer omkring 1900 ............................................................................................ 3 1.2.1 Company towns og hagebybevegelsen ........................................................................... 3 1.2.2 «Egne-hjem» ................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Teoretisk byplanteori – noen begreper ................................................................................... 5 1.4 Arkitektur - Typiske stiltrekk fra perioden 1905 – 1920 .......................................................... 6 1.4.1 Nasjonal byggeskikk ........................................................................................................ 6 1.4.2 Jugendstilen ..................................................................................................................... 7 1.4.3 Nyklassisismen ................................................................................................................. 7 1.4.4 Sveitserstil: 1840 - 1920 .................................................................................................. 8 1.5 Landskaps- og naturmessige forutsetninger på Rjukan: -

World Architecture 1900-2000: a Critical Mosaic Volume 3

WORLD ARCHITECTURE 1900-2000: A CRITICAL MOSAIC VOLUME 3 NORTHERN EUROPE, CENTRAL EUROPE AND WESTERN EUROPE General Editor: Kenneth Frampton Volume Editor: Wilfried Wang bifid 3225 CHINA ARCHITECTURE & BUILDING PRESS SpringerWienNewYork CONTENTS Complimentary Remarks by Sara Topelson de Grinberg, Past President of the International Union of Architects (UIA) XI Complimentary Remarks by Vassilis Sgoutas, President of the International Union of Architects (UIA) XII Complimentary Remarks by Ye Rutang, President of the Architectural Society of China (ASC) - A Recrord of 20th Century World Architecture XII General Introduction by Kenneth Frampton XIV Introductory Essay by Wilfried Wang XVH Selected Buildings (in chronological order of years of design) 1900-1919 The Stock Exchange, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1885, 1898-1903, arch. Hendrik P. Berlage 4 House of the People, Brussels, Belgium, 1895-1899, arch. Victor Horta 6 Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow, Scotland, 1896-1899, West Wing 1907-1909, arch. Charles Rennie Mackintosh Ernst Ludwig House, Darmstadt, Germany, 1899-1900, arch. Josef Maria Olbrich Hvittrask House, Kikkonummi, Finland, 1901-1903, arch. H. Gesellius, A. Lindgren, E. Saannen St. John's Cathedral, Tampere, Finland, 1902-1907, arch. Lars Sonck Town Hall, Stockholm, Sweden, 1902, 1908-1923, arch. Ragnar Ostberg Post Office Savings Bank, Vienna, Austria, 1903-1906, 1910-1912, arch. Otto Wagner Railway Station, Helsinki, Finland, 1904, 1911-1919, arch. Eliel Saarinen Balasz Villa, Budapest, Hungary, 1905 , arch. Odon Lechner Palais Stoclet, Brussels, Belgium, 1905, 1906-1911, arch. Josef Hoffmann AEG Factory, Berlin, Germany, 1908-1909, arch. Peter Behrens Emile Jaques-Dalcroze Institute for Rhythmic Gymnastics, Hellerau, Germany, 1910, 1911-1912, arch. Heinrich Tessenow Fagus Works, Alfeld, Germany, 1911-1913, arch. -

Rdhusutkastet I Bergen 1951-1953

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Erling Viksjøs rådhusutkast i Bergen 1951-1953 Sett i en monografisk og typologisk sammenheng Berit Johanne Henjum Masteroppgave i kunsthistorie, IFIKK UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Høst 2008 I Forord For å finne noe eller for å finne noe nytt, må man ofte lete grundig eller på nye steder. Dette var bakgrunnen for at jeg, ved valg av Erling Viksjø som tema for masteroppgaven, bestemte meg for å ta utgangspunkt i rådhuset i Bergen fremfor mer kjente verk som Regjeringskvartalet eller Norsk Hydro. Selve utformingen av oppgaven samt beslutningen om å skrive om norsk etterkrigsarkitektur skyldes erfaringer fra faget KUN4132 ”Norsk arkitektur og design 1950-70”. I arbeidet med semesteroppgave i dette faget, gikk det opp for meg at jeg i grunn trivdes godt med å undersøke gammelt arkivmateriale og tidsskrifter. Jeg ønsket derfor å ta med meg denne erfaringen videre i arbeidet med masteroppgaven. I arbeidet med oppgaven har jeg fått god hjelp særlig i forbindelse med arkivsøk. I den forbindelse vil jeg takke følgende bidragsytere: Bergen byarkivs avdeling for formidling og publikumstjenester, firmaet Aas-Jakobsen og Viksjøs arkitektkontor AS. Ved Nasjonalmuseet for arkitektur har Bente Aas Solbakken vært behjelpelig med å finne frem materiale fra arkivene etter Viksjøs arkitektkontor og Nasjonalmuseets fotosamling. Takk også til Tone Viksjø Grøstad, Randi Viksjø og Herman Rolfsen for å ha tatt seg tid til å fortelle meg om arkitekten og privatpersonen Erling Viksjø. Til slutt vil jeg takke min veileder Espen Johnsen for innspill og kommentarer underveis i arbeidet. -

1930 Is Year Zero in Modern Scandinavian River Gravel, the Stern Concrete of Modernism Has Won More Prices Than Them

Norway: 80 years of modernism evident in the early post war period. Viksjø Two of the most infl uential post war archi- was faithful towards the teachings of Le tects in Norway have been Kjell Lund (b. 1927) Ulf Grønvold Corbusier, but with the aid of his invention, and Nils Slaatto (1923-2001). They set up their «natural concrete», a construction method in practice together in 1958. They had a huge which façades were livened up with exposed production of high quality. Only Sverre Fehn 1930 is Year Zero in Modern Scandinavian river gravel, the stern concrete of modernism has won more prices than them. Architecture. The famous Stockholm Exhibi- was refi ned into «stone architecture» and In the 1960s, Lund & Slaatto7 designed tion that year, with Gunnar Asplund as its Norwegian nature appeared on walls after they compact buildings that often took on cubic or main architect, introduced a new world to a were sandblasted. pyramidal shape. In the 1970s, they developed broad mass audience. The white buildings This was a golden compromise that many a structuralistic mode of operation that was along shores of Djurgårdsbrunnsviken con- found appealing. Among them were Christian redeveloped in the 1980s to accommodate vinced the general public that this future was Norberg-Schulz and PAGON (Progressive new assignments and urban environments. a very desirable world. After that, Modernism, Architects Group Oslo Norway), which in They have been instrumental in renewing or Functionalism as it was called, was the the 1950s represented a more unadulter- Norwegian wood architecture and their church dominant building style in the Nordic countries. -

Villa Ditlev-Simonsen (1936-37)

Villa Ditlev-Simonsen (1936-37) En studie av den visuelle fremstillingen av Ove Bangs moderne villa gjennom tegneprosess og fotografi Malene Borghild Helgeland Masteroppgave i kunsthistorie Institutt for filosofi, idé- og kunsthistorie og klassiske språk Det humanistiske fakultet Veileder: Espen Johnsen UNIVERSITET I OSLO Våren 2014 II Sammendrag Denne masteroppgaven er en arkitekturhistorisk prosessuell undersøkelse av Ove Bangs Villa Ditlev-Simonsen. Oppgavens mål har vært å kartlegge Ove Bangs prosessuelle arbeid med villaen, fra han fikk oppdraget og utarbeidet skisser og utkast frem til villaen ble fotografert og bebodd av familien. Men det har også vært et mål å belegge og diskutere fotograf Karl Teigens fotografier av det ferdige bygget. Villa Ditlev-Simonsen ble tegnet av Ove Bang og oppført i årene 1936-1937 og er et av den norske funksjonalismens mer kjente verk. Både i tegninger og fotografier av verket kommer nærheten mellom arkitektur og landskap godt frem. Det er interessant at trær og planter får så stor plass i bildet som primært ofte skal vise det arkitektoniske verket, særlig i fotografiene. Derfor har jeg vært opptatt av å studere dette aspektet av Villa Ditlev-Simonsen og knytte det til Bangs mulige forbilder. En meget sentral kilde for denne undersøkelsen har vært arkitekturtegninger, fotografier og dokumenter fra arkitekten Ove Bangs arkiv hos Nasjonalmuseet - Arkitektur. En samling med uregistrerte fotografier i Bangs arkiv er den største kilden til ny informasjon om modeller av villaen og om Bangs forberedelser av materiale til utstilling. Flere fotografier av Villa Ditlev-Simonsen, tatt av Teigen, var også å finne hos DEXTRA Photo på Teknisk Museum. -

Villa Ditlev-Simonsen

Villa Ditlev-Simonsen Introduksjon Villa Ditlev-Simonsen i Hoffsjef Løvenskiolds vei 32 på Ullern i Oslo er tegnet av Ove Bang etter bestilling fra Johan I. Ditlev-Simonsen. Bygningen stod ferdig i 1937 og er i dag residensen til den amerikanske ministerråd. Beskrevet av Sigfried Giedion som “like godt som Le Corbusier”, etablerte Villa Ditlev-Simonsen Bang som en av 1930-årenes fremste villa-arkitekter, og den internasjonalt anerkjente bygningen er blitt stående som et hovedverk innen norsk modernisme, eller “funksjonalisme” som retningen ofte blir kalt i en nordisk kontekst.1 Ove Bang (1895-1942), arkitekt Arkitekt Ove Bang studerte ved arkitekturavdelingen på Høyskolen i Trondheim (NTNU) i perioden 1913 til 1917. Etter uteksaminering, begynte Bang som assistent hos Magnus Poulsson (1881-1958) før han i 1919 flyttet til Rjukan for å arbeide for Norsk Hydro ved Rjukan byanlegg. I 1922 etablerte han her sin egen praksis, og bygningene han tegnet mens han bodde på Rjukan inkluderer en rekke eneboliger samt sorenskrivergården, politimesterboligen og fjellbanens stasjonsbygning. Bangs arkitektur fra tiden hos Poulsson og på Rjukan er en blanding av nyklassisisme og nasjonale tradisjoner, som var de dominerende stilretningene i norsk arkitektur i de første tjue årene av 1900-tallet. For Bang endret dette seg da han på en studiereise til Nederland med Arkitektforeningen i 1928 fikk oppleve de modernistiske byggene til Willem Marinus Dudok (1884-1974), J. J. P. Oud (1890-1963), Johannes Brinkman (1902-1949) og Leendert van der Vlugt (1894-1936). I følge hans samtidige biografer, arkitektene Gudolf Blakstad og Herman Munthe-Kaas, betydde turen et gjennombrudd for Bangs arkitektoniske visjon.2 Det var de hollandske arkitektenes klare og enkle volumer og rene, dekorfrie fasader som tiltrakk Bang. -

Architectural Competitions NORDISK ARKITEKTURFORSKNING NORDIC JOURNAL of ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH

NORDISK ARKITEKTURFORSKNING NORDIC JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH N2/3.2009 A Architectural Competitions NORDISK ARKITEKTURFORSKNING NORDIC JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH 2/3.2009 ARTIKLENE ER GRANSKET AV MINST TO AV FØLGENDE FORSKERE: GERD BLOXHAM ZETTERSTEN, Associate Professor Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Institute of Art and Cultural Studies, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen YLVA DAHLMAN, PhD, Senior Lecture Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala ROLF JOHANSSON, Professor Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala REZA KAZEMIAN, Associate professor Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm PETER THULE KRISTENSEN, Lecture Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art, Copenhagen STEN GROMARK, Professor Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg SATU LAUTAMÄKI, Eon PhD Design Center MUOVA, Vasa HANS LIND, Professor Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm MAGNUS RÖNN, Associate professor Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm BRIGITTA SVENSSON, Professor Stockholm University, Stockholm INGA BRITT WERNER, Associate professor Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm ÖRJAN WIKFORSS, Professor Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm LEIF ÖSTMAN, PhD Swedish Polytechnic, Vasa KOMMENDE TEMA I NORDISK ARKITEKTURFORSKNING: Architecture, Climate and Energy Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2/3-2009 Innhold: Vol. 21, No 2/3.2009 NORDISK ARKITEKTURFORSKNING – NORDIC JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH TEMA: ARCHITECTURAL COMPETITIONS 4 In memory – Minneord 5 Architectural Competition – Editors’ notes JONAS E ANDERSSSON, -

De Padre a Hijo Dos Cabañas En Portør

De padre a hijo Dos cabañas en Portør Elisa Ricoy Castro De padre a hijo. Dos cabañas en Portør Elisa Ricoy Castro Tutora Graziella Trovato Departamento de Composición Arquitectónica Aula TFG 4 Jorge Sainz Avia, coordinador Ángel Martínez Díaz, adjunto Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Resumen El presente trabajo destaca la importancia de una arquitectura domés- tica de carácter modesto, que parece querer esconderse entre la naturaleza, resultando casi invisible, con el deseo de unirse a ella y así formar un hogar para el ser humano. De esta forma, la exploración y el entendimiento del Ge- nius loci de la costa sur de Noruega se hace imprescindible para entender el lenguaje empleado por Knut y Bengt Knutsen, padre e hijo respectivamente, en sus cabañas de Portør. Ambas viviendas de verano, conside-radas obras maestras de la arquitectura nórdica, se convierten en la arquitectura más íntima construida por y para los Knutsen. Con el fin de entender la heren- cia de un pensamiento que surge en respuesta a un marco histórico, físico y teórico específico se analiza la relación entre ambas cabañas. Knut Knutsen, Espen Knutsen, Christian Norberg-Schulz, domesticidad, ca- baña, Noruega, lugar Abstract This work highlights the importance of a modest domestic architectu- re, which tries to hide among nature, transforming itself into something almost invisible and thus be-coming a home for the human being. In this way, the analysis and understanding of the Genius loci of the south coast of Norway becomes essential in order to understand the architectural langua- ge used by Knut and Bengt Knutsen -father and son respec-tively- in their cabins in Portør. -

As a Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, from 1915 He Gave Well

The absolute monarchy was abolished almost As a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, Postscript: a glimpse to nordic by the king himself in 1849, and 1901’s change from 1915 he gave well-attended lectures in traditions in political systems was equally peaceful. In the history of art and architecture. Witnesses all areas there is a belief in evolution. People explain that it provided them with a holistic should accept the new. That was in the spirit vision. His book: The Aesthetic Perception of of Grundtvig. There was no tabula rasa in Dan- Art (1906) was read by everyone. Wanscher Antonio Millán-Gómez ish architecture, but on the contrary a will to especially accentuated Italian baroque, and his innovate, which resembles several European infl uence can be sensed already in Faaborg Few things are so scarce in Architecture as models such as C.F.A. Voysey’s speech on Museum, but also in Fisker’s Hornbækhus proper acts, coherent with the essence of styles at “the Design Club” in 1911, Le Cor- (Hornbæk House) 1922, in the inner yards of things. And few as needed as the enthused busier’s writings, and the Design-development Politigården (The Police Headquarters) 1924, glance to their authentic contexts, which in and social commitment of the Bauhaus School. in relation to which Aage Rafn play a crucial Nordic Architecture are dialogues, inseparable Everything was to be digested and in the part, and in the ny Scene (new Stage) at The from a way of life caring for nature and an ele- words of Jensen-Klint: “…since the beauty of Royal Theatre 1929 by Holger Jacobsen gance based on lightness. -

Armert Betong Sprenger Seg Plass På Fredningslista Siktlinja

RIKSANTIKVARENS MAGASIN ALLE TIDERS Ingierstrand Stupetårnet ferdig restaurert. Side 7 På kanten – Fysisk fostring er like viktig som kulturbygg. Jan Erik Vold Side 16 – Jeg fant, jeg fant! Marcus var en av 80 unger på leit etter skålgroper fra steinalderen. Side 30 Ta del i middel- alderens klosterliv Spillet om Hovedøya i eget bilag Armert betong sprenger seg plass på fredningslista SIKTLINJA ETT ÅR SOM RIKSANTIKVAR Det har vært et begivenhetsrikt, lærerikt Joakim Krøvel/www.krovel.com Foto: og utfordrende første år for meg som riksantikvar. I løpet av dette året er det særlig ett aspekt som slår meg. Kulturminner er som tomme hylstre uten historiene. Historiene om oss, historien om menneskene i tilknytning til husmannsplassen, maskinanlegget eller fartøyet, må fortelles sammen. I dette nummeret av Alle tiders har arkitektur og materialet betong fått stor plass. Labora- torieblokka på Ullevål sykehus, som er avbildet på forsiden, gjorde sterkt inntrykk på meg da jeg så den første gang på slutten av 70-tallet. Den er ikke bare brutal og majestetisk, den forteller også en historie om velferdsstatens utvikling inn i modernismen. Kulturminner der ute i alle kommuner forteller unike historier om oss. Disse historiene har vi ansvaret for å fortelle til kommende generasjoner. Riksantikvaren har et ansvar, men også fylkeskommunene og kommunene selv. Det reelle kulturminnevernet har i for stor grad vært overlatt til eierne av fredede kultur- minner, men også noen ildsjeler og de frivillige. Det offisielle vernet oppfattes i noen tilfeller som et fjernt og stivt saksbehandlingsvesen. I en sak ble eieren av et fredet våningshus fra 1820 nektet av fylkeskonservatoren å utvide et tilbygg fra 1920 med èn meter for at barna skulle få et soverom.