The Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

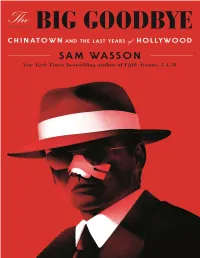

The Big Goodbye

Robert Towne, Edward Taylor, Jack Nicholson. Los Angeles, mid- 1950s. Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on the author, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For Lynne Littman and Brandon Millan We still have dreams, but we know now that most of them will come to nothing. And we also most fortunately know that it really doesn’t matter. —Raymond Chandler, letter to Charles Morton, October 9, 1950 Introduction: First Goodbyes Jack Nicholson, a boy, could never forget sitting at the bar with John J. Nicholson, Jack’s namesake and maybe even his father, a soft little dapper Irishman in glasses. He kept neatly combed what was left of his red hair and had long ago separated from Jack’s mother, their high school romance gone the way of any available drink. They told Jack that John had once been a great ballplayer and that he decorated store windows, all five Steinbachs in Asbury Park, though the only place Jack ever saw this man was in the bar, day-drinking apricot brandy and Hennessy, shot after shot, quietly waiting for the mercy to kick in. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Political Aesthetic of Irony in the Post-Racial United States Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8fd7t1ph Author Jarvis, Michael Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Political Aesthetic of Irony in the Post-Racial United States A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Michael R. Jarvis March 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jennifer Doyle, Chairperson Dr. Sherryl Vint Dr. Keith Harris Copyright by Michael R. Jarvis 2018 The Dissertation of Michael R. Jarvis is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the support of my committee, Professors Jennifer Doyle, Sherryl Vint, and Keith Harris. Thank you for reading this pile of words, for your feedback, encouragement, and activism. I am not alone in feeling lucky to have had each of you in my life as a resource, mentor, critic, and advocate. Thank you for being models of how to be an academic without sacrificing your humanity, and for always having my back. A thousand times, thank you. Sincere thanks to the English Department administration, UCR’s Graduate Division, and especially former Dean Joe Childers, for making fellowship support available at a crucial moment in the writing process. I was only able to finish because of that intervention. Thank you to the friends near and far who have stuck with me through this chapter of my life. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

6-1773 (304) 232 -1773 the Morning Fax 1 Po Bos 965

^iyj . .. S ef SJ . ,a ¡sc r2 ! .7 /y+{) lw tT q = ./<q :/ 1 «/% ( !J V S! u` + '` i_.. ÿ'. 'Ì,-.``.... MT.T;ylF Fii ti+j:. ' Jtr» 1. .:.,...50p,..1..., r'`1:yLj f¡h y:v+s.?,J I'°v'", ` `' ,;Vdlr.yt s _i .. Z? . rr1. s,;/ /:?'-yS,;"S J'>c,Z . ¿ S . r 7+ ' 2. ¡ Z. r ; / rt ' ? i i :, i4;< ydSAiNl! ._..,ti:C;A.sv3t;..;s,i,:tixtir!Vt::vr`.C3:_í?I.icäitr..:.v,;,V ,Yÿt\ ?l,`. ^}T !^.j e . v ^ >v sfie..- 7,.v+1r.Y,;ÿ( `'tZ t -1 3 SN ! ` vV ? C r ¡ S!` ?AM 5. - .T i? Ps' ..L-..,?-t . s:-}``:{ This Week v , ,s.s., .:--., z"`: - . .I' } ; We don't need no education...we don't need no thought 5 control...Rock and roll has always been about breaking rules. Radio, seeking to reflect w the music and culture, tries, . : I Q too, to rebel $ . :Q0 a^A ~ - .' 't against the , + . r-?ÿ^ S2 ry.,+ y, Fr xl ., teachings of ?i' . - `kGKA ) {ti i: /.^'i :4 -: ytÇ^^.C 1 jb^i.l.9t the pioneers, yyyéro9;:t. v5 =1Si i1t Z: j .Ky . ' *p < YC+c : '.-r^ :i ? y ^gp.7 who ' ! htiJ}.mJ those y. ,-J. ..,..: >j : jeJi`fK' r 4,:.1=oLC. came up with the first Top 40 surveys, the first rotations, the theories about playing the hits and saying what you're playing. With the massive changes that have taken place in radio in recent years, more pro- grammers are beginning to won- der: Is it time to get back to the basics? In the view of two whose views LN_ should count, it's high time. -

Yo Yo Ma Discography Free Download

yo yo ma discography free download Grand Funk Railroad – Discography (1969 – 2002) Grand Funk Railroad – Discography (1969 – 2002) EAC Rip | 56xCD | FLAC/WV Tracks & Image + Cue + Log | Full Scans Included Total Size: 21.3 GB | 3% RAR Recovery STUDIO ALBUMS | LIVE ALBUMS | COMPILATIONS Label: Various | Genre: Hard Rock, Blues Rock. One of the 1970s’ most successful hard rock bands in spite of critical pans and somewhat reluctant radio airplay (at first), Grand Funk Railroad built a devoted fan base with constant touring, a loud, simple take on the blues-rock power trio sound, and strong working-class appeal. The band was formed by Flint, MI, guitarist/songwriter Mark Farner and drummer Don Brewer, both former members of a local band called Terry Knight & the Pack. They recruited former ? & the Mysterians bassist Mel Schacher in 1968, and Knight retired from performing to become their manager, naming the group after Michigan’s well-known Grand Trunk Railroad. They performed for free at the 1969 Atlanta Pop Festival, and their energetic, if not technically proficient, show led Capitol Records to sign them at once. While radio shied away from Grand Funk Railroad, the group’s strong work ethic and commitment to touring produced a series of big- selling albums over the next few years; five of their eight releases from 1969 to 1972 went platinum, and the others all went gold. Meanwhile, Knight promoted the band aggressively, going so far as to rent a Times Square billboard to advertise Closer to Home, which turned out to be the band’s first multi-platinum album in spite of a backlash from the rock press. -

Μ Ziq 13Th Floor Elevators Adam F Add N to X Aerial M Aimee Man Air Air

Intérprete µ Ziq 13th Floor Elevators Adam F Add N To X Aerial M Aimee Man Air Air Air Air Akufen Al Green Alex Gopher Alfie Alpha Alpha Alphaville Amon Düül II Amon Tobin Animals That Swim Anna Karina Annie Ross Anton Webern Antonio Carlos Jobin and Friends April March April March AR Kane Arab Strap Arnold Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Arthur Lyman Astor Piazzola & Gery Mulligan Astrud Gilberto Astrud Gilberto Audioweb Bach Barbara Morgenstern Barry Adamson Barry Adamson Barry White Bebel Gilberto Beethoven Benny Carter Benny Carter Benny Goodman Benny Goodman Bernard Herrman Bertha Hope Trio Beth Gibbons & Rustin Man Betty Page Bil Evans & Jim Hall Bill Evans Billie Holiday Billie Holiday Billie Holiday Björk Björk Björk Black Box Recorder Black Box Recorder Blue Note Bluebird Bobby Darin Bobby Vinton Bobby Womack Boris Vian Bowery Electric Brad Mehldau Brenda Lee Brian Wilson Brigitte Bardot Brigitte Fontaine Bryan Ferry Bryan Ferry / Roxy Music Bud Powell Burt Bacharach Burt Bacharach Burt Bacharach Cabaret Voltaire Call and Response Can Can Cannonball Audrey Carla Bruni Carmen Mc Rae Cassandra Wilson Cassius Centurions Charles Mingus Charles Mingus Charles Mingus Charles Trenet Charlie Parker Charly Garcia Chet Baker Chet Baker Chet Baker Chick Corea Chopin Chopin Clan of Xymox The Clash Claude Debussy Clinic Cloudberry Jam Coldplay Coleman Hawkins Coleman Hawkins Combustible Edison Va Connie Francis Console Console Console Cornelius Cornelius Count Basie Creation -

The DIT Examiner: the Newspaper of the Dublin Institute of Technology Students' Union October, 1997

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin DIT Student Union Dublin Institute of Technology 1997 The DIT Examiner: the Newspaper of the Dublin Institute of Technology Students' Union October, 1997 DIT Students's Union Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ditsu Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation DIT Students' Union: The DIT Examiner, October, 1997. DIT, 1997 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Dublin Institute of Technology at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in DIT Student Union by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License the DITExaminer So apart from being the largest DITSU, DIT Kevin Street, Kevin St., Dublin 8. Pb:402 4636 students' union in the country Fax: 478 3154 What has Dffsu ever done for me? Well we organise and provide: + FRESHERS/ARTS/WELFARE/RAG WEEKS + COMPREHENSIVE SUBSIDISED ENTS. + FREE WELFARE ADVICE + FREE FINANCIAL ADVICE + HELP WITH COURSE PROBLEMS VOTE + HELP WITH GRANT PROBLEMS + HELP AND RESOURCES FOR CLUBS AND SOCIETIES + FREE STUDENT NEWSPAPERS AND MAGAZINES + REPRESENTATION WITHIN THE COLLEGE, WITHIN OIT GOVERNING BODY AND NATIONALLY + CAMPAIGNS ON ISSUES LIKE STUDENT HARDSHIP, ACCOMMODATION AND SAFETY, LIBRARY FACILITIES, CATERING + RAISES THOUSANDS FOR CHARITY THROUGH RAG WEEK + 2ND HAND BOOK SERVICE + PUBLISHES FREE YEARLY HANDBOOK AND WELFARE MANUAL + DETAILED ACCOMMODATION LIST AT START OF EVERY YEAR + INTEREST FREE WELFARE LOANS + USIT CARDS + CHEAP PHOTOCOPYING + SU SHOP WITH WIDE RANGE OF PRODUCTS AT COMPETITIVE PRICES + SECRETARIAL SERVICE, PAST EXAM PAPERS AND FAX SERVICE + POOL TABLES AND VIDEO GAMES + PAYPHONE IN SU OFFICE + CONDOM MACHINES IN TOILETS + FRESHERS, HALLOWEEN, CHRISTMAS, RAG, EASTER, LAST CHANCE BALLS + FASHION SHOW :": . -

Ejesus LIZARD $

S t ? te 0 A Au 0 30 Ile t AMP GUIDED BY VOICES CM Bee Thousand •Scat-Matador 111 WORLD SAXOPHONE QUARTET neel tcath Of Life •Elektra Nonesuch °II. VELOCITY GIRL i,S11111)(1IiCO! • Still 1)011 WARREN G Regulate... G Funk Era • Violator/ RAL-PG VOL. 39 NO. 1 • ISSUE #384 VNIJ! report .; FRANK BLACK eJESUS LIZARD SURE THING ! $ JESUS LIZARD INSIDE I Bad Livers On Page 3 I Guest Dialogue From Hammerhead the new album: featuring "hypocrite" Produced by Mike Hedges and Lush Management: Howard Gough ,:.)1994 4•A•O Page 3• .• V; BAD LIVERS DOING THEIR OWN THING: MAKING BAD LIVER MUSIC They ore particularly pleased with the outcome of their latest record, Horses In The Mines. Banjo player Danny Barnes describes it as "a slice of life," to which Rubins adds, "it's just a picture of what we were doing that week, like a Although Austin, Texas' Bad Livers are often pigeonholed after the first pluck of grainy snapshot." The record was recorded in a shed, using on-site analog the banjo, the band's inspirations go beyond the obvious influence of bluegrass. "What inspired me to be a musician in the first place is what is historically recording techniques, and incorporated impromptu bits (such as Judy the won- referred to as the hardcore/punk rock scene of the early '80s," says stand-up der dog barking (singing?) on "New Bad Liver Singer"). This record best cap- tures what the band does live. "The idea was to make a more organic record," bassist Mark Rubins.