Derrida's Kafka and the Imagined Boundary of Legal Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic

ISSN 1393-614X Minerva - An Internet Journal of Philosophy 11 (2007): 128-152 ____________________________________________________ The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic Abstract In order to show that both Derrida’s epistemology and his ethics can be understood in terms of his logic of writing and giving, I consider his conversation with Searle in Limited Inc. I bring out how a deconstruction that is implied by the dissemination of writing and giving makes a difference that accounts for the creative and responsible decisions that undecidability makes possible. Limited Inc has four parts and I will interpret it in terms of the four main concepts of Derrida. I will relate signature, event, context to Derrida’s notion of dissemination and show how he differs from Austin and Searle concerning the notion of the signature of the one who writes and gives. Next, I will show how in his reply to Derrida, entitled, “Reiterating the Differences”, Searle overlooks Derrida’s thought about the communication of intended meaning that has to do with Derrida’s distinction between force and meaning and his notion of differance. Here I will show that Searle cannot even follow his own criteria for doing philosophy. Then by looking at Limited Inc, I show how Derrida differs from Searle because repeatability is alterability. Derrida has an ethical intent all along to show that it is the ethos of alterity that is called forth by responsibility and accounted for by dissemination and difference. Of course, comments on comments, criticisms of criticisms, are subject to the law of diminishing fleas, but I think there are here some misconceptions still to be cleared up, some of which seem to still be prevalent in generally sensible quarters. -

Pedagogies of Justice : Critical Approaches to Public Legal Education

BIROn - Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Pedagogies of justice : critical approaches to public legal education https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/44178/ Version: Full Version Citation: Wintersteiger, Lisa (2020) Pedagogies of justice : critical ap- proaches to public legal education. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through BIROn is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Pedagogies of justice Critical approaches to public legal education Lisa Wintersteiger School of Law Birkbeck, University of London. Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy for the University of London August 2019 Declaration I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own, except where explicit reference is made to the work of others. 2 Abstract Public legal education is generally understood as a set of informal educational practices aimed at improving access to justice and social cohesion that predominantly focus on marginalised or disadvantaged populations. Public knowledge of law and its associated informational and educational practices provide a decisive locus for the legitimizing function of the normative ideal of the rule of law with its underpinning assumptions of security and stability. These ideals occlude a legacy of violence and political oppression that haunt the legal order, an erasure that is perpetuated when legal education is inattentive to its political- philosophical underpinnings. The pivotal role of public legal knowledge also carries the possibility of alternative critical engagements with justice systems that fundamentally interrogate the juridical-political order. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

The Law Is Not a Thing: Kafkan (Im)Materialism and Imitation Jam

Law Text Culture Volume 23 Legal Materiality Article 14 2019 The Law is Not a Thing: Kafkan (Im)materialism and Imitation Jam James R. Martel San Francisco State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Martel, James R., The Law is Not a Thing: Kafkan (Im)materialism and Imitation Jam, Law Text Culture, 23, 2019, 240-261. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol23/iss1/14 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Law is Not a Thing: Kafkan (Im)materialism and Imitation Jam Abstract In this article, I look at the question of how the law continually refounds itself in relationship to the material world by borrowing from that materiality a sense of its own tangibility (which it otherwise does not have) even as it in turn draws material orbits into its object lending them a certain sense of power and nobility (which they otherwise do not have either). This exchange suggests an unexpected vulnerability for the law insofar as it needs the material world to exist at all while the material world does not require an association with the law per se (and arguably is worse off in terms of the exchange it engages with the law insofar as it becomes complicit, at least by association, with law and it various forms of violence). To demonstrate a bit of that vulnerability I look at a US supreme course case 62 Cases of Jam v. -

Derrida in the University, Or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction / C

Derrida in the University, or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction / C. Kelly 49 CSSHE SCÉES Canadian Journal of Higher Education Revue canadienne d’enseignement supérieur Volume 42, No. 2, 2012, pages 49-66 Derrida in the University, or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction Colm Kelly St. Thomas University ABSTRACT Derrida’s account of Kant’s and Schelling’s writings on the origins of the mod- ern university are interpreted to show that theoretical positions attempting to oversee and master the contemporary university find themselves destabilized or deconstructed. Two examples of contemporary attempts to install the lib- eral arts as the guardians and overseers of the contemporary university are examined. Both examples fall prey to the types of deconstructive displace- ments identified by Derrida. The very different reasoning behind Derrida’s own institutional intervention in the modern French university is discussed. This discussion leads to concluding comments on the need to defend pure re- search in the humanities, as well as in the social and natural sciences, rather than elevating the classical liberal arts to a privileged position. RÉSUMÉ Le compte-rendu de Derrida sur les écrits de Kant et de Schelling portant sur les origines de l’université moderne démontre que des positions théoriques tentant de surveiller et de gouverner l’université contemporaine se trouvent déstabilisées et déconstruites. L’auteur étudie deux exemples de tentatives contemporaines visant à donner aux arts libéraux le statut de gardiens et de surveillants de l’université contemporaine. Les deux exemples en question ne tiennent pas la route devant les substitutions déconstructives identifiées par Derrida. -

Franz Kafka, Lawrence Joseph, and the Possibilities of Jurisprudential Literature

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2011 Franz Kafka, Lawrence Joseph, and the Possibilities of Jurisprudential Literature Patrick J. Glen Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 11-22 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/967 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1768093 21 S. Cal. Interdisc. L.J. 47-94 (2011) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Courts Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Society Commons FRANZ KAFKA, LAWRENCE JOSEPH, AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF JURISPRUDENTIAL LITERATURE PATRICK J. GLEN* I. INTRODUCTION What does a tubercular Czech Jew, born and raised in Prague, who died in June 1924, have in common with a Maronite Catholic of mixed Lebanese and Syrian descent, born and raised in Detroit during the 1950s and 1960s, and who currently haunts the streets of twenty-first century New York City? If the Czech Jew is Franz Kafka and the Maronite Detroiter is Lawrence Joseph, there are far more similarities than one may expect considering the expanse of time and space separating their lives and experiences.1 Both studied and eventually practiced law: Kafka in the context of insurance, employment, and workers compensation, and Joseph with the international law firm of Shearman & Sterling.2 Kafka was a short story writer and novelist while Joseph is an acclaimed poet and novelist.3 In both of their literary works, law and legal themes are often at the center of their writings. -

Jacques Derrida Law As Absolute Hospitality

JACQUES DERRIDA LAW AS ABSOLUTE HOSPITALITY JACQUES DE VILLE NOMIKOI CRITICAL LEGAL THINKERS Jacques Derrida Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality presents a comprehensive account and understanding of Derrida’s approach to law and justice. Through a detailed reading of Derrida’s texts, Jacques de Ville contends that it is only by way of Derrida’s deconstruction of the metaphysics of presence, and specifi cally in relation to the texts of Husserl, Levinas, Freud and Heidegger, that the reasoning behind his elusive works on law and justice can be grasped. Through detailed readings of texts such as ‘To Speculate – on Freud’, Adieu, ‘Declarations of Independence’, ‘Before the Law’, ‘Cogito and the History of Madness’, Given Time, ‘Force of Law’ and Specters of Marx, de Ville contends that there is a continuity in Derrida’s thinking, and rejects the idea of an ‘ethical turn’. Derrida is shown to be neither a postmodernist nor a political liberal, but a radical revolutionary. De Ville also controversially contends that justice in Derrida’s thinking must be radically distinguished from Levinas’s refl ections on ‘the Other’. It is the notion of absolute hospitality – which Derrida derives from Levinas, but radically transforms – that provides the basis of this argument. Justice must, on de Ville’s reading, be understood in terms of a demand of absolute hospitality which is imposed on both the individual and the collective subject. A much needed account of Derrida’s infl uential approach to law, Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality will be an invaluable resource for those with an interest in legal theory, and for those with an interest in the ethics and politics of deconstruction. -

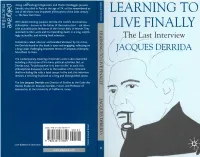

Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally the Last Interview

ZJ ~T~} 'Along with Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, Jacques Q, Qj Derrida, who died in Paris at the age of 74, will be remembered as —— one of the three most important philosophers of the 20th century.' LEARNING TO >*J — The New York Times r— ^-» With death looming, Jacques Derrida, the world's most famous __ *T\ philosopher - known as the father of 'deconstruction' - sat down ~' with journalist Jean Birnbaum of the French daily Le Monde. They LIVE FINALLY revisited his life's work and his impending death in a long, surpris• ingly accessible, and moving final interview. The Last Interview Sometimes called 'obscure' and branded 'abstruse' by his critics, the Derrida found in this book is open and engaging, reflecting on a long career challenging important tenets of European philosophy 'ACOUES DERRIDA from Plato to Marx. The contemporary meaning of Derrida's work is also examined, including a discussion of his many political activities. But, as Derrida says, 'To philosophize is to learn to die'; as such, this philosophical discussion turns to the realities of his imminent death-including life with a fatal cancer. In the end, this interview remains a touching final look at a long and distinguished career. The late Jacques Derrida was Director of Studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, France, and Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine. ISBN 978-0-230-53785-9 9 780230 537859 Cover illustration © Carol Hayes Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally The Last Interview Jacques Derrida An Interview with Jean Birnbaum Translated by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas With a bibliography by Peter Krapp All rights reserved. -

As a Foreign Language: Rereading Deleuze and Derrida

Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics 12(1), 29-46 The Becoming-Philosophy as a Foreign Language: Rereading Deleuze and Derrida Immanuel Kim University of California, Riverside Kim, I. (2008). The becoming-philsophy as a foreign language: Rereading Deleuze and Derrida. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 12(1), 29-46. This paper will revisit French theorists, Gilles Deleuze and Jacques Derrida, on the notion of the future of philosophy. Although their approaches to the future (devenir [to become] for Deleuze and á venir [to come] for Derrida) of philosophy may differ, I will argue that their differences allow for a space of congruence and continuity in the not only the field of philosophy but in every academic field. The question of the future of philosophy needs to be addressed because of the “crisis” that each academic department seems to face with every new faculty appointment, influx in student registration, applying for funding, etc. Each and every department in the university context seems to have the need to “justify” and validate the purpose of that discipline. I am not proposing another theory for theory’s sake, but a call to deeply reconsider and re-evaluate the philosophy of and in each department. After all, faculty members who are not even “involved” in the philosophy department still possess a PhD. Key Words: Deleuze, Derrida, philosophy 1 An Attempt to Find a Place for Philosophy Where does [philosophy] find today its most appropriate place? (Derrida, 2002, p.3) Where would we begin to reread these two thinkers? From what point should we begin? Would a rereading proffer an ethical reading of their respective philosophies? What can these thinkers offer to the field of linguistics? What relationship does philosophy (especially with these French thinkers) have with applied linguistics? What are the pragmatics of philosophy in the field research of applied linguistics? I will attempt to find a “place” where philosophy can enter even in the field of linguistics in order to iterate the importance of pragmatic research. -

Taboo As a Means of Accessing the Law in Kafka's Works Taylor

Taboo as a Means of Accessing the Law in Kafka’s Works Taylor Sullivan Professor Flenga Ramapo College of New Jersey In a number of Franz Kafka’s works exists a totemic trend—a trend, which involves sexualized gestures carried out between exclusively male characters. The characters’ gestures attempt to achieve fulfillment; however, all are stopped short. Their indefinite impotence, their inability to arrive, mocks a parallel inability on their part to penetrate the law. The mirrored relationships of Kafka’s male characters with sexual fulfillment and nonphysical penetration culminate in “In The Penal Colony.” This short story confirms that Kafka’s male characters exist permanently as the countryman in “Before the Law”—outside of the door, unaware of and 1 unable to access what lies beyond. Such exclusively homoerotic relationships though ignore women. Kafka’s male characters, through gestures that confirm their gender’s unchanging position, leave the positioning of women to question. What Kafka eventually reveals is that if men remain indefinitely before the law, women exist outside of the law entirely. The guiltless attitudes of his female characters confirm their role as permanent outlaws. The root of Kafka’s totemic trend lies in the relationship between the law and prohibition. 2 In his essay, “Before the Law,” Derrida explains that the law is “a prohibited place.” In this 3 4 way, “to not gain access to the law” is “to obey the law.” Conversely, to gain access to the law 5 would be to transgress the very law to which one is gaining access; “the law is prohibition.” Paradoxically then, what the countryman seeks is as much the law as it is prohibition—synonymous beings that exist beyond the door. -

Violence and Life in the Work of Jacques Derrida and Theodor Adorno

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2012 Critical ecologies: Violence and life in the work of Jacques Derrida and Theodor Adorno Richard L. Elmore II DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Elmore, Richard L. II, "Critical ecologies: Violence and life in the work of Jacques Derrida and Theodor Adorno" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 117. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEPAUL UNIVERSITY Chicago, Illinois CRITICAL ECOLOGIES: VIOLENCE AND LIFE IN THE WORK OF JACQUES DERRIDA AND THEODOR ADORNO A dissertation completed in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Rick Elmore 2011 Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………. 2 2. Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………. 3 3. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 4 4. Chapter One: Violence in the Work of Jacques Derrida……………………….. 13 i. Originary Reparations: The “Violence” Before “Violence”……. 14 ii. Lévi-Strauss and The Violence of Ethnocentrism ………………. 27 iii. Four Characteristics of Reparatory Violence …………………... 34 5. Chapter Two: Derrida and the Critique of Non-Violence ……………………... 43 i. Philosophy at the Threshold of Death: Levinas, Violence, and Subjectivity ………………………………………………………... 44 ii. -

Authority, Autonomy, and Choice: the Role of Consent in the Moral and Political Visions of Franz Kafka and Richard Posner

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 1985 Authority, Autonomy, and Choice: The Role of Consent in the Moral and Political Visions of Franz Kafka and Richard Posner Robin West Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 11-04 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/489 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1737920 99 Harv. L. Rev. 384 (1985-1986) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons AUTHORITY, AUTONOMY, AND CHOICE: THE ROLE OF CONSENT IN THE MORAL AND POLITICAL VISIONS OF FRANZ KAFKA AND RICHARD POSNER Robin West* Law-and-economics theorist Richard Posner has argued that principles of consent support wealth maximization as a rule of judicial decisionmaking. According to Posner, wealth-maximizing consensual transactions are morally desirable because they promote both well-being and autonomy. In this Ar- ticle, Professor West draws on Franz Kakfa's depictions of human motivation to dispute the empirical basis of both justificatory prongs of Posner's thesis. Kafka's characters, she argues, suggest that when individuals consent to transactions,they often do so because of a desire to submit to authority, and not to maximize well-being or autonomy. Thus, Professor West concludes, Posner's identification of consent as the moral justification of wealth max- imization rests on an inadequate view of human motivation.