Collectively Empathizing with the ‘Innocent Victim’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NPO-Fonds Presentatie Cijfers 2018

CIJFERS 2018 Gebaseerd op 1 jaar feitelijke gegevens NPO-fonds (met uitzondering van de diverse talentontwikkelingstrajecten) !1 ALGEMEEN 2018 !2 Hoeveel aanvragen zijn er in totaal bij het NPO-fonds ingediend en toegekend? 2018 !3 TOTAAL INGEDIENDE AANVRAGEN Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 160 153 140 120 100 89 81 80 72 60 47 40 42 40 30 24 15 20 10 9 0 Video drama Video documentaire Audio Totaal 2018 !4 TOTAAL TOEGEKENDE AANVRAGEN Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 100 91 90 80 70 56 60 51 50 40 40 28 28 30 22 17 20 13 7 10 5 6 0 Video drama Video documentaire Audio Totaal 2018 !5 TOTAAL SLAGINGS% Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 100% 80% 67% 67% 63% 63% 60% 59% 60% 57% 55% 54% 50% 52% 47% 40% 20% 0% Video drama Video documentaire Audio Totaal 2018 !6 Hoe is de verhouding tussen indieningen en toekenningen per omroep? 2018 !7 TOTAAL INGEDIEND PER OMROEP Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 40 34 34 35 30 25 26 25 19 18 20 15 16 16 15 13 15 12 11 9 9 10 7 8 5 4 4 4 5 1 0 1 0 EO MAX NTR VPRO HUMAN BNNVARA AVROTROS KRO-NCRV 2018 !8 TOTAAL TOEGEKEND PER OMROEP Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 25 20 19 20 18 18 15 13 9 10 10 9 9 10 7 8 7 5 6 5 3 3 5 2 1 0 0 0 0 EO MAX NTR VPRO HUMAN BNNVARA AVROTROS KRO-NCRV 2018 !9 2018 59% 52% 63% 69% Gemiddeld 60% 82% VPRO 80% 78% 81% NTR Totaal 0% 0% MAX 53% 50% Productie 56% !10 54% KRO-NCRV 50% OMROEP 56% HUMAN 56% Ontwikkeling 53% EO 60% 38% 75% TOTAAL SLAGINGS% PER 0% 50% BNNVARA 20% 71% AVROTROS 0% 20% 10% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% Hoeveel geld is er in totaal toegekend? 2018 !11 2018 € 15.978.099 € 8.927.107 € 7.251.100 -

Jarin Van Oort

Curriculum Vitae - Jarin van Oort Persoonlijke gegevens: Volledige naam en titel: ing. Jasper Christiaan (Jarin) van Oort Adres: Smidsgilde 21, 3994 BG Houten Telefoonnummer: 06-16408076 E-mail: [email protected] LinkedIn profiel: linkedin.com/in/jarin Geboortedatum: 26 november 1976 Professionele werkervaring: 2011 – heden: Leading Projects (Houten) Zelfstandig Projectmanager in ICT / Multimedia • 18 jaar achtergrond in Telecom/Broadcasting (HTS Telematica, KPN, Imtech, EO, Solcon, NPO, AVROTROS, BVN TV, KRO-NCRV, e.a.) en Universiteit Leiden • Ervaren in specialistische ICT-projecten: Streaming Video, IPTV, Multimedia, Telecom en Infrastructuur, 24/7 realtime omgevingen Recente opdrachtgevers: § KRO-NCRV (National Broadcaster) 2017 Sr. Projectmanager&Consultant Vernieuwing externe netwerk-infrastructuur KRO-NCRV (firewalls, glasvezel- infrastructuur TV / Radio / Data); Verbeteronderzoek Videomontage-workflow; Coaching teamleiders (Agile, projectleiding); Sparring partner t.b.v. ICT-manager Marktoriëntaties (Ericsson, NEP, KPN, etc.), Programma van Eisen, Aanbesteding, Implementatie § Universiteit Leiden 2014-2016 Sr. Projectmanager&Consultant Aanbesteding en implementatie Cloud Video Platform t.b.v. 30.000 users; Integratie in Blackboard (SSO); Publieke portal (video.leidenuniv.nl); SAML-integratie campus Identity Management; Migratie video content; Opstart supportorganisatie Programma van Eisen; Aanbesteding; Pilots; Leveranciersmanagement; Stuurgroep; Supportproces § AVROTROS (National Broadcaster) 2015 Consultant Onderzoek -

Journalistieke Televisie Op Youtube Een Analyse Van Drie Journalistieke NPO-Programma’S Op Youtube

Journalistieke televisie op YouTube Een analyse van drie journalistieke NPO-programma’s op YouTube Masterscriptie Jules Ruijs Jules Ruijs [email protected] Studentnummer: 11132833 Masterscriptie Jules Ruijs Universiteit van Amsterdam Journalistiek en Media Research en redactie voor audiovisuele media Scriptiebegeleider: dr. P.L.M. Vasterman Tweede lezer: E.K. Borra MSc Inleverdatum: 6 februari 2017 Aantal woorden: 22.604 Versie: Definitief Keywords: journalistiek, innovatie, YouTube, NPO, vloggers Voorwoord L.S., Dit voorwoord is het laatste officiële onderdeel dat ik schrijf als student. Na precies zeven jaar studeren in drie verschillende steden komt er een (voorlopig) einde aan deze periode. Dit is voor mij dan ook een bijzonder moment. Uiteindelijk hebben alle tegenslagen in de afgelopen zeven jaar geleid tot deze scriptie. Zonder de lessen die ik trok uit mijn moeizame bachelorscriptie, of het niet halen van tentamens tijdens mijn premaster had ik deze scriptie dan ook nooit kunnen schrijven. Daar hebben niet al die talloze docenten bij geholpen, maar ook mentoren in het werkveld. Deze scriptie was er ook zeker niet geweest zonder mijn klasgenoten van dit jaar. Ik weet nog goed hoe één van die klasgenoten in een hoekje van het redactielokaal van de UvA in zijn eentje hardop zat te lachen achter een laptop. Op die laptop een aflevering van #BOOS. Mijn interesse was gewekt. Met dit onderwerp kon ik een scriptie schrijven over journalistiek, iets dat ons allen bindt aan deze master. Maar nog leuker, ik kon een scriptie schrijven die te maken had met televisie en formatontwikkeling. De combinatie van journalistiek, televivsie en formats is een combinatie waar je me ’s nachts voor wakker mag maken. -

Jaarverslag Nederlands Letterenfonds 2018

ederlands N letterenfonds dutch foundation for literature Jaar verslag 2018 Inleiding 3 Hoofdstuk 1 4 Missie en samenwerkingsverbanden Hoofdstuk 2 7 2.1 Creatie Creatie, productie, — Regelingen 7 innovatie, zichtbaarheid — Programma’s 9 Binnenland 2.2 Productie — Regelingen 15 — Programma: Schwob 15 2.3 Innovatie — Regelingen digitale literatuur 16 — Programma: Literatuur op het Scherm 16 2.4 Zichtbaarheid — Regelingen voor festivals 17 en manifestaties — Programma’s 17 — Residenties 19 — Prijzen 20 3.1 Vertaalsubsidies 22 Hoofdstuk 3 22 3.2 Talen, genres en schrijvers in cijfers 23 Internationalisering 3.3 Activiteiten van de afdeling buitenland Buitenland — Boekenbeurzen 23 — Stedenbezoeken 24 3.4 Fellowships en bezoekersprogramma 25 3.5 Focuslanden 26 3.6 Literaire manifestaties in 30 Frankrijk en Duitsland 3.7 Auteurs naar het buitenland 33 3.8 Netwerk vertalers 34 3.9 Vertalershuis Amsterdam 34 Hoofdstuk 4 36 4.1 Communicatie 36 Communicatie, kwaliteitsbeleid 4.2 Kwaliteitsbeleid en onderzoek 37 en onderzoek Hoofdstuk 5 44 5.1 Bestuur en beheer 44 Organisatie en personeel 5.2 Bezwaar, beroep en klachten 45 5.3 Personeelsbeleid / 45 Code Culturele Diversiteit 5.4 ICT 46 5.5 Huisvesting 46 5.6 Exploitatieresultaat, financiële positie, 47 realisatie doelstellingen 5.7 Risicomanagement 47 5.8 Recoupment 48 Hoofdstuk 6 49 Vooruitzichten 2019 en verder Hoofdstuk 7 50 Samenwerking rijkscultuurfondsen Bijlagen 54 1 Verslag Raad van Toezicht 54 2 Raad van advies, externe lezers & bureau 57 3 Subsidies 2018 65 4 Literaire programma’s binnenland: 99 tournees en reeksen Fotoverantwoording & colofon 108 5 Publicaties, website, sociale media 103 en voorlichting 6 Balans & exploitatierekening 106 7 Private stichtingen 110 “Ik heb in mijn vertaalleven een groot aantal kansen gekregen, op allerlei manieren van alles mogen leren, en daarvoor ben ik dankbaar. -

Miptv 2020 Producers to Watch Contents

MIPTV 2020 PRODUCERS TO WATCH CONTENTS DOC & FACTUAL 3 DRAMA / FICTION 36 FORMATS 112 KIDS & TEENS 149 DOC & FACTUAL DOC & FACTUAL PRODUCERS LISTED BY COUNTRY AUSTRIA FINLAND HUNGARY SOUTH AFRICA COLLABORATE: IDEAS & IMAGES GS FILM FILM-& FERNSEHPRODUKTION AITO MEDIA SPEAKEASY PROJECT HOMEBREW FILMS Lauren Anders Brown E.U. Erna AAlto László Józsa Jaco Loubser EMPORIUM PRODUCTIONS Gernot Stadler GIMMEYAWALLET PRODUCTIONS OKUHLE MEDIA Emma Read Phuong Chu Suominen IRELAND Pulane Boesak IMPOSSIBLE DOC & FACTUAL BELGIUM RAGGARI FILMS FELINE FILMS Adam Luria CLIN D’ŒIL Minna Dufton Jessie Fisk SPAIN WOODCUT MEDIA Hanne Phlypo BRUTAL MEDIA Matthew Gordon FRANCE JAPAN Raimon Masllorens BELGIUM COLLABORATION INC 4TH DOC & FACTUAL TAMBOURA FILMS UNITED STATES EKLEKTIK PRODUCTION Bettina Hatami Toshikazu Suzuki Xaime Barreiro CREATIVE HEIGHTS ENTERTAINMENT Tatjana Kozar Jaswant Dev Shrestha BLEU KOBALT KOREA ZONA MIXTA CANADA Florence Sala GINA DREAMS PRODUCTION Robert Fonollosa GALAXIE Sunah Kim DBCOM MEDIA SWITZERLAND Nicolas Boucher Thierry Caillibot GEDEON PROGRAMMES PERU SLASH PRODUCTION TORTUGA Jean-Christophe Liechti Adam Pajot Gendron Maya Lussier Seguin PACHA FILMS URBANIA MÉDIAS HAUTEVILLE PRODUCTIONS Luis Del Valle UNITED KINGDOM Philippe Lamarre Karina Si Ahmed POLAND ALLEYCATS ILLEGITIME DEFENSE Desmond Henderson CHINA Arnaud Xainte KIJORA FILM Anna Gawlita BIG DEAL FILMS - UNSCRIPTED DA NENG CULTURE MEDIA YUZU PRODUCTIONS Thomas Stogdon Hengyi Zhi Christian Popp PORTUGAL CHALKBOARD TV ENCOUNTER MEDIA Simon Cooper Qi Zhao PANAVIDEO Diana Nunes SHUTTER BUG STUIO(BEIJING) Hongmiao Yu GS FILM FILM-& FERNSEHPRODUKTION E.U. AUSTRIA My previous works & partners : We have produced over 70 documentaries/docu-dramas and documentary series on various topics such as human interest, history, culture and nature. -

Cabrillo Festival of Contemporarymusic of Contemporarymusic Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor Marin Alsop Music Director |Conductor 2015

CABRILLO FESTIVAL OFOF CONTEMPORARYCONTEMPORARY MUSICMUSIC 2015 MARINMARIN ALSOPALSOP MUSICMUSIC DIRECTOR DIRECTOR | | CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR SANTA CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM CRUZ CIVIC AUDITORIUM SANTA BAUTISTA MISSION SAN JUAN PROGRAM GUIDE art for all OPEN<STUDIOS ART TOUR 2015 “when i came i didn’t even feel like i was capable of learning. i have learned so much here at HGP about farming and our food systems and about living a productive life.” First 3 Weekends – Mary Cherry, PrograM graduate in October Chances are you have heard our name, but what exactly is the Homeless Garden Project? on our natural Bridges organic 300 Artists farm, we provide job training, transitional employment and support services to people who are homeless. we invite you to stop by and see our beautiful farm. You can Good Times pick up some tools and garden along with us on volunteer + September 30th Issue days or come pick and buy delicious, organically grown vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers. = FREE Artist Guide Good for the community. Good for you. share the love. homelessgardenproject.org | 831-426-3609 Visit our Downtown Gift store! artscouncilsc.org unique, Local, organic and Handmade Gifts 831.475.9600 oPen: fridays & saturdays 12-7pm, sundays 12-6 pm Cooper House Breezeway ft 110 Cooper/Pacific Ave, ste 100G AC_CF_2015_FP_ad_4C_v2.indd 1 6/26/15 2:11 PM CABRILLO FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC SANTA CRUZ, CA AUGUST 2-16, 2015 PROGRAM BOOK C ONTENT S For information contact: www.cabrillomusic.org 3 Calendar of Events 831.426.6966 Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary -

Jaarverslag 2019 Vereniging Investeer in Human

Jaarverslag 2019 Vereniging Investeer in Human Vereniging Investeer in Human | Handelsnaam: Human Zetel (statutaire vestigingsplaats): Hilversum Feitelijk gevestigd: Wim T. Schippersplein 1 | 1217 WD Hilversum | KvK nummer: 57906289 Inhoudsopgave Bestuursverslag Voorwoord 4 Human algemeen 6 Media-aanbod met impact 8 Op weg naar volledige erkenning 18 Vereniging Investeer in Human 21 Bedrijfsvoering 24 Realisatie 2019 28 Begrotingsjaar 2020 29 Uitgangspunten financieel beleid 30 Risicomanagement, compliance en governance 31 Coronacrisis en toekomst 41 Verklaring governance en interne beheersing 43 Jaarrekening Balans per 31 december 2019 (na resultaatbestemming) 45 Exploitatierekening 2019 volgens de categoriale indeling 47 Toelichting op de exploitatierekening over 2019 per kostendrager (Model IV) 48 Toelichting op nevenactiviteiten per cluster 2019 (Model VI) 50 Kasstroomoverzicht over 2019 51 Sponsorbijdragen en bijdragen van derden 2019 (Model VII) 52 Sponsorbijdragen en bijdragen van derden 2019 via buitenproducenten 52 Programmakosten per domein per platform 2019 (Model IX) 54 Grondslagen voor waardering van activa en passiva en resultaatbepaling 55 Toelichting op de balans per 31 december 2019 59 Toelichting op de exploitatierekening 2019 65 Gebeurtenissen na balansdatum 73 Overige gegevens 74 Resultaatbestemming 74 Goedkeuring Raad van Toezicht 75 Controleverklaring onafhankelijke accountant 76 Jaarverslag 2019 | 2 Bestuursverslag Jaarverslag 2019 | 3 Voorwoord 2019 was in meerdere opzichten een belangrijk jaar voor Human. Op 14 juni maakte minister Slob in zijn ‘Visie toekomst publiek omroepbestel: waarde voor het publiek’ bekend dat het kabinet voornemens is het minimumaantal leden voor de huidige aspirant-omroepen te verlagen van 150.000 naar 50.000 betalende leden. In het vertrouwen dat de maatregel in 2020 wettelijk verankerd wordt, is hiermee in één klap de kans groot dat de Vereniging Investeer in Human in 2022 als volwaardige omroep toetreedt tot het publieke omroepbestel. -

2021 Country Profiles

Eurovision Obsession Presents: ESC 2021 Country Profiles Albania Competing Broadcaster: Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSh) Debut: 2004 Best Finish: 4th place (2012) Number of Entries: 17 Worst Finish: 17th place (2008, 2009, 2015) A Brief History: Albania has had moderate success in the Contest, qualifying for the Final more often than not, but ultimately not placing well. Albania achieved its highest ever placing, 4th, in Baku with Suus . Song Title: Karma Performing Artist: Anxhela Peristeri Composer(s): Kledi Bahiti Lyricist(s): Olti Curri About the Performing Artist: Peristeri's music career started in 2001 after her participation in Miss Albania . She is no stranger to competition, winning the celebrity singing competition Your Face Sounds Familiar and often placed well at Kënga Magjike (Magic Song) including a win in 2017. Semi-Final 2, Running Order 11 Grand Final Running Order 02 Australia Competing Broadcaster: Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) Debut: 2015 Best Finish: 2nd place (2016) Number of Entries: 6 Worst Finish: 20th place (2018) A Brief History: Australia made its debut in 2015 as a special guest marking the Contest's 60th Anniversary and over 30 years of SBS broadcasting ESC. It has since been one of the most successful countries, qualifying each year and earning four Top Ten finishes. Song Title: Technicolour Performing Artist: Montaigne [Jess Cerro] Composer(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer Lyricist(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer About the Performing Artist: Montaigne has built a reputation across her native Australia as a stunning performer, unique songwriter, and musical experimenter. She has released three albums to critical and commercial success; she performs across Australia at various music and art festivals. -

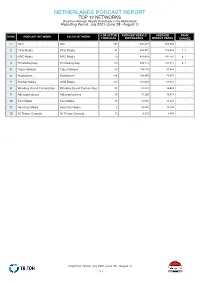

NETHERLANDS PODCAST REPORT TOP 12 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads in the Netherlands Reporting Period: July 2021 (June 28 - August 1)

NETHERLANDS PODCAST REPORT TOP 12 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads in the Netherlands Reporting Period: July 2021 (June 28 - August 1) RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES NETWORK # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE PODCASTS DOWNLOADS WEEKLY USERS CHANGE 1 NPO Ster 385 1,683,887 580,259 - 2 DPG Media DPG Media 81 690,475 339,039 2 3 NRC Media NRC Media 10 450,899 192,791 1 4 FD Mediagroep FD Mediagroep 110 349,214 142,321 1 5 Talpa Network Talpa Network 65 238,328 97,649 - 6 Audioboom Audioboom 146 138,899 70,097 - 7 Stitcher Media SXM Media 121 121,839 53,972 - 8 Wondery Brand Partnerships Wondery Brand Partnerships 81 41,312 16,639 - 9 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 25 37,266 15,079 - 10 Kast Media Kast Media 29 27,901 14,438 - 11 Next Day Media Next Day Media 5 18,526 12,499 - 12 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 12 8,242 4,385 - Reporting Period: July 2021 (June 28 - August 1) 1 of 5 NETHERLANDS PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS BY DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the Netherlands Reporting Period: July 2021 (June 28 - August 1) # OF NEW AVERAGE AVERAGE RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK EPISODES WEEKLY WEEKLY CATEGORY DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 NRC Vandaag NRC Media 25 287,017 123,854 News - 2 In Het Wiel DPG Media 72 199,393 67,796 Sports 9 3 NOS Met het Oog op Morgen NPO Radio 1 / NOS 43 127,976 36,715 News 1 Religion & 4 Eerst dit NPO Radio 5 / EO / IZB 26 118,617 45,681 Spirituality 1 5 NU.nl Dit wordt het nieuws DPG Media 49 115,035 76,460 News Debut 6 De Dag NPO Radio 1 / NOS 24 108,774 38,700 News 4 7 De Taghi -

Overzicht Registers Nevenfuncties Journalistieke Functionarissen

Index registers nevenfuncties journalistieke functionarissen Peildatum 25-04-19 In januari 2019 publiceerde CIPO haar zienswijze op de toepassing van artikel 2.10 van de Governancecode Publieke Omroep 2018 voor zover het gaat over het openbaar maken van nevenfuncties van belangrijke journalistieke functionarissen. Omdat de code geen definitie van het begrip journalistiek bevat, vindt CIPO het werkbaar als mediaorganisaties voor de toepassing van het artikel aansluiten bij het systeem van de zogenoemde CCC-codes. In de registers moeten daarom in ieder geval de nevenfuncties worden vermeld van de presentatoren (of van bijvoorbeeld hoofd- of eindredacteuren) van de als journalistieke uiting aangemerkte programma’s. In aansluiting op die publicatie inventariseerde CIPO of de media-instellingen en de NPO aan artikel 2.10 toepassing hebben gegeven. In onderstaand overzicht zijn webadressen van (en een beschrijving van de routes naar) deze openbare registers opgenomen. Uit de geïnventariseerde registers blijkt dat alle twaalf mediaorganisaties (zes omroepverenigingen, drie aspirant-omroepen, twee taakomroepen en de stichting NPO) op hun websites nevenfuncties openbaar maken, dan wel er op wijzen dat met opdrachtnemers afspraken zijn gemaakt ter voorkoming van het verrichten van functies die voor de mediaorganisatie -mede gelet op de code- ongewenst zijn. Mediaorganisaties zijn primair zelf verantwoordelijk voor het naleven van de Governancecode. CIPO toetst de naleving daarvan periodiek. AVROTROS www.avrotros.nl Topfunctionarissen: Verantwoording -

Confirmed 2021 Buyers / Commissioners

As of April 13th Doc & Drama Kids Non‐Scripted COUNTRY COMPANY NAME JOB TITLE Factual Scripted formats content formats ALBANIA TVKLAN SH.A Head of Programming & Acq. X ARGENTINA AMERICA VIDEO FILMS SA CEO XX ARGENTINA AMERICA VIDEO FILMS SA Acquisition ARGENTINA QUBIT TV Acquisition & Content Manager ARGENTINA AMERICA VIDEO FILMS SA Advisor X SPECIAL BROADCASTING SERVICE AUSTRALIA International Content Consultant X CORPORATION Director of Television and Video‐on‐ AUSTRALIA ABC COMMERCIAL XX Demand SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS AUSTRALIA Head of Business Development XXXX AUSTRALIA SPECIAL BROADCASTING SERVICE AUSTRALIA Acquisitions Manager (Unscripted) X CORPORATION SPECIAL BROADCASTING SERVICE Head of Network Programming, TV & AUSTRALIA X CORPORATION Online Content AUSTRALIA ABC COMMERCIAL Senior Acquisitions Manager Fiction X AUSTRALIA MADMAN ENTERTAINMENT Film Label Manager XX AUSTRIA ORF ENTERPRISE GMBH & CO KG content buyer for Dok1 X Program Development & Quality AUSTRIA ORF ENTERPRISE GMBH & CO KG XX Management AUSTRIA A1 TELEKOM AUSTRIA GROUP Media & Content X AUSTRIA RED BULL ORIGINALS Executive Producer X AUSTRIA ORF ENTERPRISE GMBH & CO KG Com. Editor Head of Documentaries / Arts & AUSTRIA OSTERREICHISCHER RUNDFUNK X Culture RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE BELGIUM Head of Documentary Department X COMMUNAUTE FRANCAISE BELGIUM BE TV deputy Head of Programs XX Product & Solutions Team Manager BELGIUM PROXIMUS X Content Acquisition RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE BELGIUM Content Acquisition Officer X COMMUNAUTE FRANCAISE BELGIUM VIEWCOM Managing -

Bijlage Raad Voor Cultuur Advies Omroeperkenningen

Prins Willem Alexanderhof 20 2595 BE Den Haag t 070 3106686 [email protected] www.raadvoorcultuur.nl Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap T.a.v. de heer drs. A. Slob Postbus 16375 2500 BJ Den Haag Den Haag, 28 april 2021 Kenmerk: RVC 2021 1649 Betreft: Advies omroeperkenningen Geachte heer Slob, In uw brief van 4 februari jl. vraagt u de NPO, het Commissariaat van de Media en de Raad voor Cultuur om advies over de door u ontvangen erkenningsaanvragen voor de verzorging van media-aanbod door de landelijke publieke omroepen voor de concessieperiode 2022-2026. Hierbij treft u aan het advies van de Raad voor Cultuur. 1. Inleiding De raad richt zich in zijn advies met name op de stromingseis (die u vraagt licht te toetsen), het programmabeleid van de omroepen en hun respectieve bijdragen aan de publieke mediaopdracht. Over de administratieve en juridische vereisten (notariële akten, bestuurlijke structuur, naleving Mediawet, e.d.) heeft u advies gevraagd aan het Commissariaat voor de Media. De raad heeft voor het opstellen van dit advies een commissie ingesteld onder voorzitterschap van het raadslid Erwin van Lambaart. Andere leden van de commissie waren Joop Daalmeijer, Annemarie van Gaal, Henk Hagoort, John Olivieira, Farid Tabarki en Gamila Ylstra. De commissie heeft voor haar beoordeling van de erkenningsaanvragen met alle omroepdirecties gesproken en alle ingediende plannen bestudeerd en getoetst aan de relevante bepalingen van de Mediawet en het gestelde in de adviesaanvraag. De raad deelt de conclusies die de commissie op basis van deze toetsing heeft getrokken. 1 Het advies begint met een schets van het toetsingskader.