Silenced Voices: Music of Soviet Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underserved Communities

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2016 Spring Grant Announcement Artistic Discipline/Field Listings Project details are accurate as of April 26, 2016. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Click the grant area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. 1. Art Works grants Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts 2. State & Regional Partnership Agreements 3. Research: Art Works 4. Our Town 5. Other Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of April 26, 2016. Arts Education Number of Grants: 115 Total Dollar Amount: $3,585,000 826 Boston, Inc. (aka 826 Boston) $10,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. High school students from underserved communities will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book and provided free to students. Visiting authors, illustrators, and graphic designers will support the student writers and book design and 826 Boston staff will collaborate with teachers to develop a standards-based curriculum that meets students' needs. Abada-Capoeira San Francisco $10,000 San Francisco, CA To support a capoeira residency and performance program for students in San Francisco area schools. Students will learn capoeira, a traditional Afro-Brazilian art form that combines ritual, self-defense, acrobatics, and music in a rhythmic dialogue of the body, mind, and spirit. -

Fernando Laires

Founded in 1964 Volume 32, Number 2 Founded in 1964 Volume 32, Number 2 Founded in 1964 Volume 32, Number 2 An officiIn AMemoriam:l publicAtion of the AmericFernandoAn liszt society, Laires inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 January 1925 – 9 September 2016 1 In Memoriam: Fernando Laires In Memoriam: Fernando Laires TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 January 1925 – 9 September 2016 2 President's Message In Memoriam: Fernando Laires TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 January 1925 – 9 September 2016 31 LetterIn Memoriam: from the FernandoEditor Laires 1 42In Memoriam:"APresident's Tribute toMessage Fernando Fernando Laires Laires," by Nancy Lee Harper 2 3President's Letter from Message the Editor 5 More Tributes to Fernando Laires 3 4Letter "A fromTribute the to Editor Fernando Laires," 7 Membershipby Nancy Lee Updates, Harper Etc. 4 "A Tribute to Fernando Laires," 85by NancyInvitationMore TributesLee to Harper the to 2017 Fernando ALS FestivalLaires in Evanston/Chicago 5 7More Membership Tributes to Updates, Fernando Etc. Laires 10 "Los Angeles International Liszt Competition Overview" 7 8Membership byInvitation Éva Polgár Updates, to the 2017 Etc. ALS Festival in Evanston/Chicago 8 InvitationIn Memoriam to the 2017 ALS Festival in Evanston/Chicago 10 JALS"Los AngelesUpdate International Liszt Competition Overview" 10 "Losby Angeles Éva Polgár International Liszt 11 Competition Chapter News Overview" In Memoriam by Éva Polgár 12 Member News In MemoriamJALS Update 1511JALS FacsimileChapter Update News Frontispiece of Liszt's "Dante" Symphony Fernando Laires with his wife and fellow pianist, Nelita True, in 2005. Photo: Rochester NY Democrat & Chronicle Staff Photographer Carlos Ortiz: http://www. 11 12Chapter Member News News democratandchronicle.com/story/lifestyle/music/2016/10/02/fernando-laires-eastman-liszt- 16 Picture Page obituary/91266512, accessed on November 12, 2016. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova

Compiled by Irina Kuzmina Marina Medkova English version Olga Perevezentseva Dmitry Osipenko Digital version Dmitry Osipenko Graphic Design Lilia Garifullina Theatre Union of the Russian Federation Strastnoy Blvd., 10, Moscow, 107031, Russia Tel: +7 (495) 6502846 Fax: +7 (495) 6500132 e-mail: [email protected] www.stdrf.ru Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova. Moscow, Theatre Union of Russia, April 2016 A reference book with information about the structure, locations, addresses and contacts of organisers of theatre festivals of all disciplines in the Russian Federation as of April, 2016. The publication is addressed to theatre professionals, bodies managing culture institutions of all levels, students and lecturers of theatre educational institutions. In Russian and English. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. The publisher is very thankful to all the festival managers who are being in constant contact with Theatre Union of Russia and who continuously provide updated information about their festivals for publication in electronic and printed versions of this Guide. The publisher is particularly grateful for the invaluable collaboration efforts of Sergey Shternin of Theatre Information Technologies Centre, St. Petersburg, Ekaterina Gaeva of S.I.-ART (Theatrical Russia Directory), Moscow, Dmitry Rodionov of Scena (The Stage) Magazine and A.A.Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum. 3 editors' notes We are glad to introduce you to the third edition of the Russian Theatre Festival Guide. -

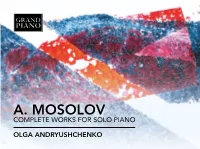

A. Mosolov Complete Works for Solo Piano

A. MOSOLOV COMPLETE WORKS FOR SOLO PIANO OLGA ANDRYUSHCHENKO 1 ALEXANDER MOSOLOV (1900-1973) COMPLETE WORKS FOR SOLO PIANO OLGA ANDRYUSHCHENKO, piano Catalogue number: GP703-04 Recording Dates: 19-22 February 2015 Recording Venue: CMS Studio, Moscow, Russia (CD1) Sovetskij Kompositor, Moscow (1 and 5), Universal Edition, Wien (2) Triton, Leningrad (1928) (3-4) (CD2) Sovetskij Kompositor, Moscow (1 and 3) Universal Edition, Wien (2) Producer and Editor: Galina Katunina Mastering Engineer: Slava Poprugin Engineer: Sergey Solodovnikov Piano Technician: Artjom Deev Piano: Steinway D Booklet Notes: Anthony Short German translation by Cris Posslac Artist photograph: Nicola Christov Composer portrait: Inna Barsova Cover Art: Tony Price: Moissac Abstract Study 4 www.tonyprice.org 2 CD 1 1 PIANO SONATA NO. 1 IN C MINOR, OP. 3 (1924) 10:55 2 NOCTURNES, OP. 15 (1925-26) 06:56 2 No. 1 Elegiaco, poco stentato 03:28 3 No. 2 Adagio 03:28 3 SMALL PIECES, OP. 23A (1927) 02:25 4 No. 1 00:55 5 No. 2 00:47 6 No. 3 00:43 2 DANCES, OP. 23B (1927) 04:17 7 No. 1 Allegro molto, sempre marcato 02:02 8 No. 2 Allegretto 02:15 PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN B MINOR, OP. 4 “FROM OLD NOTEBOOKS” (1923-24) 23:35 9 I. Sonata 10:28 0 II. Adagio 06:38 ! III. Final 06:29 TOTAL TIME: 48:06 3 CD 2 1 PIANO SONATA NO. 4, OP. 11 (1925) 11:46 TURKMENIAN NIGHTS – PHANTASY FOR PIANO (1929) 11:41 2 I. Andante con moto 04:07 3 II. Lento 05:15 4 III. -

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One 1 Ballade, Op. 49 (1939, rev. 1958)* 9:40 Romantic Episodes, Op. 88 (1962) 19:39 15 No. 1 Moderato 1:38 Four Narratives, Op. 48 (1939)* 11:25 16 No. 2 Allegro molto 1:15 2 No. 1 Andante 3:12 17 No. 3 Sostenuto, severo 3:35 3 No. 2 ‘What the sea spoke about 18 No. 4 Andantino, molto grazioso during the storm’: e rubato 0:57 Allegro impetuoso 2:00 19 No. 5 Allegro 0:49 4 No. 3 ‘What the sea spoke of on the 20 No. 6 Adagio, cantabile 3:19 morning after the storm’: 21 No. 7 Andante 1:48 Andantino, un poco con moto 3:48 22 No. 8 Allegro giocoso 2:47 5 No. 4 ‘In memory of A. M. Dianov’: 23 No. 9 Sostenuto, lugubre 1:35 Andante, molto cantabile 2:25 24 No. 10 Tempestoso e maestoso 1:56 Piano Sonata No. 8 in B flat, Op. 50 TT 71:01 (1939–44)** 15:00 6 I Allegretto giocoso 4:21 Kyung-Ah Noh, piano 7 II Andante cantabile e pensieroso 3:24 8 III Energico. Con moto assai 7:15 *FIRST RECORDING; **FIRST RECORDING ON CD Echoes of the Theatre, Op. 60 (mid-1940s)* 14:59 9 No. 1 Aria: Adagio molto cantabile 2:27 10 No. 2 Galliarde and Pavana: Vivo 3:20 11 No. 3 Chorale and Polka: Andante 2:57 12 No. 4 Waltz: Tempo di valse tranquillo 1:32 13 No. 5 Dances in the Square and Siciliana: Quasi improvisata – Allegretto 2:24 14 No. -

INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SOUND, TECHNOLOGY, AND MODERNISM TECHNOLOGY, SOUND, THOMAS PATTESON THOMAS FOR NEW MUSIC NEW FOR INSTRUMENTS INSTRUMENTS PATTESON | INSTRUMENTS FOR NEW MUSIC Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserv- ing and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribu- tion to this book provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Curtis Institute of Music, which is committed to supporting its faculty in pursuit of scholarship. Instruments for New Music Instruments for New Music Sound, Technology, and Modernism Thomas Patteson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activi- ties are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2016 by Thomas Patteson This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY- NC-SA license. To view a copy of the license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses. -

MEMORIAL Leningrad Were Buried During World War II

NO. 3 1795 САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ-ТАЙМС WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 29, 2014 WWW.SPTIMES.RU DMITRY LOVETSKY / AP LOVETSKY DMITRY Valentina Kiseleva, 76, who remained in Leningrad during the blockade, walks past a wreath at the Piskaryovskoye Cemetery where most victims of the Siege of MEMORIAL Leningrad were buried during World War II. More than 1 million people died during the 872-day siege, which was finally lifted on Jan. 27, 1944. SOCHI BUSINESS Billion-Dollar Postal Blues LOCAL Doubts Linger Blockade Over Games Survivors Honored With less than ten days to go The Boris Eifman before they start, the Sochi troupe honors Olympics are still dividing Consumers caught up in battle veterans. Page 3. local opinion. Page 8. over e-commerce. Page 6. LocalNews www.sptimes.ru | Wednesday, January 29, 2014 ❖ 2 Local Activists Protest in Kiev VK Founder Durov By Sergey Chernov THE ST. PETERSBURG TIMES Sells Stake in Website St. Petersburg’s liberal and left-wing ac- tivists have offered their support to the RIA NOVOSTI said it was probably based on the protests currently taking place in Pavel Durov, the founder of company’s value of $3-4 billion. Ukraine with one-man rallies and pick- VKontakte, said on Jan. 24 that he Previous media reports said ets, a vigil and visits to Kiev. Pickets had sold his stake in the immensely that Durov and his VKontakte have been held near the Consulate Gen- popular social-networking website team were planning to quit and eral of Ukraine and on Nevsky Prospekt that has often been dubbed “Rus- engage in a new project, but his since mid-week while on Jan. -

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 69, February, 2015 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089-4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740-2735 Fax: (213) 740-8550; E: [email protected] website: http://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the sixty-ninth biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in August of last year. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the fall and winter of 2014. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2013 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 for overseas airmail). RUSSIA. Instead of the customary editorial note, we are pleased to publish this nostalgic reminiscence by Alexander Zholkovsky, professor of Slavic languages and literatures at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. The Gift I'm not very good at giving presents. Nobody taught me to do this at an early age and I still don't know how to. Taking along a bottle of wine or, worst case scenario, a box of chocolates for the hostess, not to mention presenting colleagues with copies of my books, well, that's not a problem. But offering bouquets of flowers or perfumes to ladies of the heart, well, I could count such cases on one hand alone and, in any case, such affairs do bear an increasingly foreign fragrance. -

Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Koenig Books Isbn 978-3-86560-706-5 Early 20Th Century Russia · Andrey Smirnov

SOUND IN Z Russia, 1917 — a time of complex political upheaval that resulted in the demise of the Russian monarchy and seemingly offered great prospects for a new dawn of art and science. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, artists and enthusiasts developed innumerable musical and audio inventions, instruments and ideas often long ahead of their time – a culture that was to be SOUND IN Z cut off in its prime as it collided with the totalitarian state of the 1930s. Smirnov’s account of the period offers an engaging introduction to some of the key figures and their work, including Arseny Avraamov’s open-air performance of 1922 featuring the Caspian flotilla, artillery guns, hydroplanes and all the town’s factory sirens; Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre; Alexei Gastev, the polymath who coined the term ‘bio-mechanics’; pioneering film maker Dziga Vertov, director of the Laboratory of Hearing and the Symphony of Noises; and Vladimir Popov, ANDREY SMIRNO the pioneer of Noise and inventor of Sound Machines. Shedding new light on better-known figures such as Leon Theremin (inventor of the world’s first electronic musical instrument, the Theremin), the publication also investigates the work of a number of pioneers of electronic sound tracks using ‘graphical sound’ techniques, such as Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, Nikolai Voinov, Evgeny Sholpo and Boris Yankovsky. From V eavesdropping on pianists to the 23-string electric guitar, microtonal music to the story of the man imprisoned for pentatonic research, Noise Orchestras to Machine Worshippers, Sound in Z documents an extraordinary and largely forgotten chapter in the history of music and audio technology. -

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS a Discography Of

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers H-P GAGIK HOVUNTS (see OVUNTS) AIRAT ICHMOURATOV (b. 1973) Born in Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia. He studied clarinet at the Kazan Music School, Kazan Music College and the Kazan Conservatory. He was appointed as associate clarinetist of the Tatarstan's Opera and Ballet Theatre, and of the Kazan State Symphony Orchestra. He toured extensively in Europe, then went to Canada where he settled permanently in 1998. He completed his musical education at the University of Montreal where he studied with Andre Moisan. He works as a conductor and Klezmer clarinetist and has composed a sizeable body of music. He has written a number of concertante works including Concerto for Viola and Orchestra No1, Op.7 (2004), Concerto for Viola and String Orchestra with Harpsicord No. 2, Op.41 “in Baroque style” (2015), Concerto for Oboe and Strings with Percussions, Op.6 (2004), Concerto for Cello and String Orchestra with Percussion, Op.18 (2009) and Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op 40 (2014). Concerto Grosso No. 1, Op.28 for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, Piano and String Orchestra with Percussion (2011) Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp (2009) Elvira Misbakhova (viola)/Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + Concerto Grosso No. 1 and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) ARSHAK IKILIKIAN (b. 1948, ARMENIA) Born in Gyumri Armenia. -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No.