Draft Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Disaster Recovery of Public Housing in Galveston, Texas: an Opportunity for Whom?

2019 INQUIRY CASE STUDY STUDY CASE INQUIRY Post-Disaster Recovery of Public Housing in Galveston, Texas: An Opportunity for Whom? JANE RONGERUDE AND SARA HAMIDEH LINCOLN INSTITUTE OF LAND POLICY LINCOLN INSTITUTE OF LAND POLICY 1 TOPICS Disaster Recovery, Social Vulnerability Factors, Post-Disaster Planning, Public Housing Replacement Strategies TIMEFRAME 2008–2014 LEARNING GOALS • Understand the concept of social vulnerability and the role of its factors in shaping post-disaster recovery outcomes • Analyze examples to identify post-disaster recovery goals and to explain disparities in recovery outcomes among both public housing residents and units • Develop criteria for evaluating post-disaster recovery planning strategies to ensure fairness and inclusiveness • Analyze the goals and strategies for replacing affordable housing after disasters from different stakeholders’ perspectives PRIMARY AUDIENCE Planning students and housing officials PREREQUISITE KNOWLEDGE This case study assumes that readers have a foundational understanding of the concept of social vulnerability, which provides a framework for evaluating a community’s resilience and for understanding the ability of particular groups to anticipate, withstand, and recover from shocks such as natural disasters. This concept acknowledges that disaster risk is not distributed evenly across a population or a place. Because poor neighborhoods overall have fewer resources and more limited social and political capital than their more affluent counterparts, they face greater challenges in post-disaster recovery. Damage due to natural disasters is modulated by social factors such as income, race, ethnicity, religion, age, health, and disability status. Because poor people are more likely to live in low-quality housing, they are at greater risk for damage from high winds, waves, flooding, or tremors (Peacock et al. -

Wasn't That a Mighty Day Galveston Hurricane Song Prompt Folk Song

Wasn’t That a Mighty Day Galveston Hurricane Song Prompt Folk song lyrics are often flawed with respect to facts. This results from generations passing along verses which, though fraught with emotion, are sometimes lacking facts. Also, needing rhyming words may inject error into historical accuracy. The purpose of this prompt is to assess the accuracy of the lyrics of a popular song about the 1900 Galveston hurricane, Wasn’t That a Mighty Day? There are at least six errors/exaggerations among the verses listed below. After reading the account below, write a one page double-spaced essay describing your findings. I remember one September, When storm winds swept the town; The high tide from the ocean, Lord, Put water all around. Chorus: Wasn't that a mighty day, A mighty day A mighty day, Great God, that morning When the storm winds swept the town! There was a sea-wall there in Galveston To keep the waters down, But the high tide from the ocean, Lord, Put water in the town. The trumpets warned the people, 'You'd better leave this place!' But they never meant to leave their homes Till death was in their face. The trains they all were loaded With people leaving town; The tracks gave way to the ocean, Lord, And the trains they went on down. Great Galveston Storm Article Paraphrased from Wikipedia Information At the end of the 19th century, the city of Galveston, Texas was a booming city with a population of approximately 38,000 residents. Its position on the natural harbor of Galveston Bay along the Gulf of Mexico made it the center of trade and the biggest city in the state of Texas. -

2019 Holiday Programming.Pdf

PICK UP YOUR HOLIDAY BROCHURES AND POSTERS AT PARK BOARD PLAZA OR CALL 409.797.5151. November 15, 2019 - January 12, 2020 ONGOING HOLIDAY EVENTS AN EVENING WITH WILLIE CHARLES DICKENS’ A SANTA HUSTLE HALF NELSON & FAMILY AT THE CHRISTMAS CAROL AT THE MARATHON & 5K SANTA SIGHTINGS ISLAND ETC PRESENTS: A TUNA GRAND GRAND Dec 15 CHRISTMAS Nov 19 Dec 6 – 7 PHOTOS WITH SANTA AT Nov 8 – 30 THE 5 BROWNS – HOLIDAY AT MOODY GARDENS VIENNA BOYS CHOIR – VICTORIAN HOLIDAY HOMES THE GRAND Nov 16 – Dec 24 GALVESTON RAILROAD CHRISTMAS IN VIENNA AT THE TOUR Dec 21 MUSEUM PRESENTS THE POLAR GRAND Dec 6 SANTA AT THE GRAND 1894 EXPRESS™ TRAIN RIDE Nov 22 DON’T DROP THE BALL! NEW OPERA HOUSE (EDNA’S ROOM Nov 15 – Dec 29 PIPE ORGAN EXTRAVAGANZA AT YEAR’S CELEBRATION AT HOLIDAY ART MARKET) JASTON WILLIAMS IN BLOOD & TRINITY EPISCOPAL CHURCH ROSENBERG LIBRARY Nov 30 FREE HOLIDAY IN THE GARDENS HOLLY – CHRISTMAS WEST OF Dec 7 Dec 26 FREE Nov 16 – Jan 12 THE PECOS AT THE GRAND SUNDAY BRUNCH WITH SANTA OLIVER’S ALLEY, AT DICKEN’S RUDOLPH, THE RED-NOSED AT HOTEL GALVEZ MOODY GARDENS ICE LAND: Nov 23 – 24 ON THE STRAND SPONSORED REINDEER AT THE GRAND Dec 1, 8, 15 & 22 CHRISTMAS AROUND THE HOTEL GALVEZ HOLIDAY BY GALVESTON CHILDREN’S Dec 28 WORLD LIGHTING CELEBRATION MUSEUM FAMILY FREE NIGHT WITH Nov 16 – Jan 12 Nov 29 FREE Dec 7 – 8 HAPPY NEW YEAR, VIENNA SANTA AT THE GALVESTON STYLE! GALVESTON SYMPHONY CHILDREN’S MUSEUM MOODY GARDENS FESTIVAL ARTWALK FAMILY DAY AT THE OCEAN ORCHESTRA AT THE GRAND Dec 5 OF LIGHTS Nov 30 FREE STAR DRILLING RIG MUSEUM Jan 5 FREE Nov -

(Handsome Johnny) Roselli Part 6 of 12

FEDERAL 1-OF TNVEESTIGAFHON JOHN ROSELLI EXCERPTS! PART 2 OF 5 e --. K3 ,~I FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION Q Form No. 1 _ 4. Tr-us castORIGINATED AT §'fA,3H_[_NG1D1qiQ: FILE ]_]& NO. IIOITHADIAT . '1.. ' » 'DATIWHINMADI I PERIOD!-ORWHICH MADE E I 1, ' Is, TENT!sss 10-s-4'? 110- I. - CHARACTIR OF CA-BE %I LOUISc%:mAc1n., was,er AL sznssar P1'".ROLE TQTTER _ ___ . ._ . est . SYNOPSIS OF FACTS: Judge T. sasBEa92t*ILsoN statesletters received from priests and citizens in Chicago recommending subjects be paroled were accepted in good faith, and inquiries were not made relative to character and reputation of persons from whom letters received. states EldVi5eIS for_§ll five subjects were investigated by Chief Pro- bation Officer, Chicago, Illinois. Judge WILSONdenies knogng adviers. Judge WIISONhad been contacted by a I I if I I .- numhbr of Congressmen relative to paroling of prisoners, buttas not contacted by any Congressmanin instant ' I -» '-1,. ._ . case. Judge WILSON had been contacted by officials in e Department regarding paroling of prisoners, but was=not contacted by anyone in the Department in con- nec¬Eon with the subjects of this case. Judge'WllSON states that whenever recommendations of Congressmen and officials of Department were not inconsistent with facts and merits of case under consideration, he went along with their suggestions. Judge WILSON emphasized, however, that his decision.with respect to the paroling of any individual had never been influenced by a Con- gressman, an official of the Department, or anyone else. -

Galveston, Texas

Galveston, Texas 1 TENTATIVE ITINERARY Participants may arrive at beach house as early as 8am Beach geology, history, and seawall discussions/walkabout Drive to Galveston Island State Park, Pier 21 and Strand, Apffel Park, and Seawolf Park Participants choice! Check-out of beach house by 11am Activities may continue after check-out 2 GEOLOGIC POINTS OF INTEREST Barrier island formation, shoreface, swash zone, beach face, wrack line, berm, sand dunes, seawall construction and history, sand composition, longshore current and littoral drift, wavelengths and rip currents, jetty construction, Town Mountain Granite geology Beach foreshore, backshore, dunes, lagoon and tidal flats, back bay, salt marsh wetlands, prairie, coves and bayous, Pelican Island, USS Cavalla and USS Stewart, oil and gas drilling and production exhibits, 1877 tall ship ELISSA Bishop’s Palace, historic homes, Pleasure Pier, Tremont Hotel, Galveston Railroad Museum, Galveston’s Own Farmers Market, ArtWalk 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS • Barrier Island System Maps • Jetty/Breakwater • Formation of Galveston Island • Riprap • Barrier Island Diagrams • Town Mountain Granite (Galveston) • Coastal Dunes • Source of Beach and River Sands • Lower Shoreface • Sand Management • Middle Shoreface • Upper Shoreface • Foreshore • Prairie • Backshore • Salt Marsh Wetlands • Dunes • Lagoon and Tidal Flats • Pelican Island • Seawolf Park • Swash Zone • USS Stewart (DE-238) • Beach Face • USS Cavalla (SS-244) • Wrack Line • Berm • Longshore Current • 1877 Tall Ship ELISSA • Littoral Zone • Overview -

National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works English and Technical Communication 01 Jan 2005 Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933 Kathleen Morgan Drowne Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/eng_teccom_facwork Part of the Business and Corporate Communications Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Drowne, Kathleen. "Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933." Columbus, Ohio, The Ohio State University Press, 2005. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page i SPIRITS OF DEFIANCE Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iii Spirits of Defiance NATIONAL PROHIBITION AND JAZZ AGE LITERATURE, 1920–1933 Kathleen Drowne The Ohio State University Press Columbus Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iv Copyright © 2005 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drowne, Kathleen Morgan. Spirits of defiance : national prohibition and jazz age literature, 1920–1933 / Kathleen Drowne. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–8142–0997–1 (alk. paper)—ISBN 0–8142–5142–0 (pbk. -

FRIENDS of THC BOARD of DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P

FRIENDS OF THC BOARD OF DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P. Almond 342 Wilkens San TX 78210 210-532-3212 512-532-3212 [email protected] Avenue Antonio Peggy Cope Bailey 3023 Chevy Houston TX 77019 713-523-4552 713-301-7846 [email protected] Chase Drive Jane Barnhill 4800 Old Brenham TX 77833 979-836-6717 [email protected] Chappell Hill Road Jan Felts Bullock 3001 Gilbert Austin TX 78703 512-499-0624 512-970-5719 [email protected] Street Diane D. Bumpas 5306 Surrey Dallas TX 75209 214-350-1582 [email protected] Circle Lareatha H. Clay 1411 Pecos Dallas TX 75204 214-914-8137 [email protected] [email protected] Street Dianne Duncan Tucker 2199 Troon Houston TX 77019 713-524-5298 713-824-6708 [email protected] Road Sarita Hixon 3412 Houston TX 77027 713-622-9024 713-805-1697 [email protected] Meadowlake Lane Lewis A. Jones 601 Clark Cove Buda TX 78610 512-312-2872 512-657-3120 [email protected] Harriet Latimer 9 Bash Place Houston TX 77027 713-526-5397 [email protected] John Mayfield 3824 Avenue F Austin TX 78751 512-322-9207 512-482-0509 512-750-6448 [email protected] Lynn McBee 3912 Miramar Dallas TX 75205 214-707-7065 [email protected] [email protected] Avenue Bonnie McKee P.O. Box 120 Saint Jo TX 76265 940-995-2349 214-803-6635 [email protected] John L. Nau P.O. Box 2743 Houston TX 77252 713-855-6330 [email protected] [email protected] Virginia S. -

To the Student Exhibitors

2014 Galveston County Science and Engineering Fair co-sponsored by Galveston College Texas A&M University at Galveston & The University of Texas Medical Branch TO THE STUDENT EXHIBITORS AND TEACHERS HOST INSTITUTION: Texas A&M University at Galveston EXHIBITION AREA: TAMUG-Mitchell Campus, Physical Education Facility/Gym (Bldg. 3018) 200 Seawolf Parkway on Pelican Island in Galveston. Friday, Feb. 07, 2014 CHECK-IN: The exhibition area in Physical Education Facility/Gym (Bldg. 3018) will be open on Friday, Feb. 07, from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. for science fair project set-up. Registration check-in, held in the gym, generally takes about 30 minutes, and you may want to have transportation wait. Students should check-in and proceed to their designated space. The exhibit area will be closed and locked Friday night. MAP & DIRECTIONS: Directions to Texas A&M University at Galveston (Mitchell campus): From Houston / Interstate 45 1. Take I-45 South from Houston across the Causeway to Galveston. 2. Exit 1C: Teichman Road. 3. Turn left at the stop light onto Harborside, go under the over-pass & continue straight at the second stop light. 4. Continue ahead through the third stoplight. At the fourth light, at the top of an overpass, turn left at the light (Seawolf Pkwy) & continue across the Causeway to Pelican Island. 5. The TAMUG/Mitchell Campus- main entrance will be on your right. From San Luis Pass & on Galveston Island 1. Take FM 3005; this will become Seawall Blvd. 2. Turn left at 61st street light. Stay in the rigtht lane. 3. -

Hurricane Guide

HOUSTON/GALVESTON HURRICANE GUIDE CAUTION HURRICANE SEASON > TROPICAL STORM BILL 2015 ©2016 CenterPoint Energy 161174 55417_txt_opt_205.06.2016 08:00 AMM Introduction Index of Pages Hurricanes and tropical storms have brought damaging winds, About the Hurricane devastating storm surge, flooding rains and tornadoes to Southeast Page 3 Texas over the years. The 1900 Galveston Hurricane remains the Storm Surge deadliest natural disaster on record for the United States with an Page 4 - 5 estimated 8000 deaths. In 2008 Hurricane Ike brought a deadly storm Zip Zone Evacuation surge to coastal areas and damaging winds that led to extended Pages6-7 power loss to an estimated 3 million customers in southeast Texas. A Winds, Flooding, and powerful hurricane will certainly return but it is impossible to predict Tornadoes Pages8-9 when that will occur. The best practice is to prepare for a hurricane landfall ahead of each hurricane season every year. Preparing Your Home, Business and Boat Pages10-11 This guide is designed to help you prepare for the hurricane season. For Those Who Need There are checklists on what to do before, during and after the storm. Assistance Each hurricane hazard will be described. Maps showing evacuation Page 12 zones and routes are shown. A hurricane tracking chart is included in Preparing Pets and Livestock the middle of the booklet along with the names that will be used for Page 13 upcoming storms. There are useful phone numbers for contacting the Insurance Tips local emergency manager for your area and web links for finding Page 14 weather and emergency information. -

Student Life and Student Services

Student Life and Student Services STUDENT ACTIVITIES Purposes and General Information: Student Activities emphasizes the holistic development of students through co- curricular experiential involvement, as well as provides professional advising support and resources for recognized student clubs and organizations at Galveston College. Membership Requirements: Information about participation in any student organization may be obtained through the Student Activities Office located in the Cheney Student Center, Room 100. Requirements and procedures for establishing a new student organization, student organization rules and regulations, and student organization advisory guidelines are also available in the Student Activities Office. The development of student organizations is determined by student interest and faculty sponsorship. Categories of organizations include: Co-curricular organizations which are pertinent to the educational goals and purposes of the College. Social organizations which provide an opportunity for friendships and promote a sense of community among students. Service organizations which promote student involvement in the community. Pre-professional and academic organizations which contribute to the development of students in their career fields. Student Clubs and Organizations Student Government Association Arabesque Cosmotology Club African American Alliance Art and Soul Club Chef’s RUS Club Computer Science Club Criminal Justice Club Cross F.I.T. Campus Ministry Club Electrical Electronics Club Film Club -

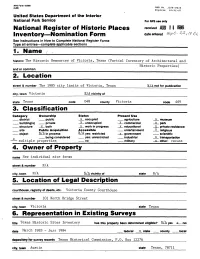

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1. Name

NFS Form 10-900 (3-82) 0MB Wo. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received AUG I I Inventory Nomination Form date entered [ri <5( See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections__________________________ 1. Name ________________________ historic The Historic Resources of Victoria, Texas (Partial Inventory of Architectural and Historic Properties) and or common____________________•__________________________ 2. Location street & number The 1985 city limits of Victoria, Texas N/A not for publication city, town Victoria N/A vicinity of state Texas code 048 county Victoria code 469 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture x museum building(s) private x unoccupied x commercial x park structure x both X work in progress x educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object N/A in process N/A yes: restricted x government scientific being considered .. yes: unrestricted __ industrial x transportation multiple properties __ "no military x other: vacant 4. Owner off Property name See individual site forms street & number N/A city, town N/A I/A vicinity of state N/A 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Victoria County Courthouse street & number 101 North Bridge Street city, town Victoria state Texas 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Texas Historic Sites Inventory has this property been determined eligible? N/A yes z_ no date March 1983 - June 1984 federal x state county local depository for survey records Texas Historical Commission, P.O. -

An Assessment of Trends and Post-Ike Plans Report One -- Prepared for the Galveston Housing Authority

Housing Galveston’s Future An Assessment of Trends and Post-Ike Plans Report One -- Prepared for the Galveston Housing Authority By Deirdre Oakley and Erin Ruel Georgia State University With assistance from Alexa Goidal Christopher Pell Brittney Terry GSU Urban Health Initiative September 2010 Deirdre Oakley, phone: 404-413-6511, email: [email protected]; Erin Ruel, phone: 404-413-6530, email: [email protected]. All photographs in the report were taken by Deirdre Oakley. Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Background 6 Galveston's History 9 Analysis of Media and Public Hearing Discourse 12 Demographic and Economic Trends 15 Analysis of Housing Trends and Reports 23 The Spatial Organization and Neighborhood Characteristics of Housing 31 Cost-Benefit Analysis of Post-Ike Plans 36 Conclusions and Recommendations 50 2 1.0 Executive Summary When Hurricane Ike struck the City of Galveston on September 12, 2008 it destroyed almost 60 percent (569 units) of the Island’s public housing, leaving the residents with few personal belongings and no home to return to. The Galveston Housing Authority (GHA) was able to secure subsidized private-market housing for the displaced public housing residents, as well as thousands of other renters who had never lived in public housing. Yet, the demand for housing assistance continued to outstrip the supply, in part because of the pervasive storm damage. Even prior to the storm, Galveston had a waiting list of about 3,000 households in need of subsidized rental housing. Nonetheless, when the GHA announced plans last year to rebuild the 569 units destroyed by Ike (390 on the same footprints of the original housing and 179 scatter-site) it encountered public opposition.