HIST 111 Sheet 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spring and Autumn Period & the Warring States Period

http://www.purpleculture.net CHINESE MUSIC Pentatonic scale friend Zhong Ziqi by Playing “Sanfen Sunyi” method It is the collective name of This was one of the ancient five musical scales: do, re, mi, the Qin have their roots in this Chinese Lü generation sol and la. All the traditional methods. Guan Zhong in the Chinese scale forms included period, which fully reflects the Spring and Autumn Period the said five scales. Various improved musical instrument invented the Sanfen Sunyi modes might be formed Method that was used to based on each tone that is playing and composing skills figure out the length of Lü considered the principal tone for the pentatonic scale. The in a sequence of music tones and the enhanced music same or similar Lü generation consisting of the pentatonic methods also appeared in scale. According to the scale appreciation skills as well. As for ancient Greek and Arabic names of the principal tones, countries. Based on length modes could fall into different playing the ancient qin, ancient of the vibrating bodies, categories, such as do-mode, qin players also attributed the Sanfen Sunyi method re-mode, mi-mode, sol-mode included two aspects: “sanfen and la-mode. superb qin performance to true sunyi” and “sanfen yiyi.” Cutting one-third from a and deep feelings. According certain chord meant “sanfen sunyi,” which could result in to historical records, the singing of famous musician the upper fifth of the chord Qin Qing in the Zhou Dynasty could “shock the trees tone; And increasing the chord by one-third meant and stop clouds from moving,” and the singing of the “sanfen yiyi,” which generated the lower quarter of the folk singer Han E could “linger in the mind for a long chord tone. -

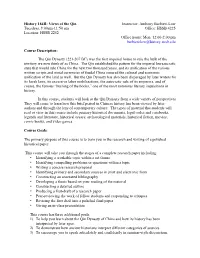

Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00Am-11:50 Am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office Hours: Mon

History 184R: Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00am-11:50 am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office hours: Mon. 12:00-2:00 pm [email protected] Course Description: The Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC) was the first imperial house to rule the bulk of the territory we now think of as China. The Qin established the pattern for the imperial bureaucratic state that would rule China for the next two thousand years, and its unification of the various written scripts and metal currencies of feudal China ensured the cultural and economic unification of the land as well. But the Qin Dynasty has also been disparaged by later writers for its harsh laws, its excessive labor mobilizations, the autocratic rule of its emperors, and of course, the famous “burning of the books,” one of the most notorious literary inquisitions in history. In this course, students will look at the Qin Dynasty from a wide variety of perspectives. They will come to learn how this brief period in Chinese history has been viewed by later authors and through the lens of contemporary culture. The types of material that students will read or view in this course include primary historical documents, legal codes and casebooks, legends and literature, historical essays, archaeological materials, historical fiction, movies, comic books, and video games. Course Goals: The primary purpose of this course is to train you in the research and writing of a polished historical paper. This course will take you through the stages of a complete research paper -

Chapter Three – the Zhou Dynasty and the Warring States

CHAPTER THREE – THE ZHOU DYNASTY AND THE WARRING STATES THE OVERTHROW OF THE SHANG As our archaeological record has proven, outside of Shang territory there existed a myriad of other kingdoms and peoples – some were allied to the Shang, others were hostile. Between the Shang capital at Anyang and the territory of the Qiang peoples, was a kingdom named Zhou. A nomadic peoples who spoke an early form of the Tibetan language, the Qiang tribes were often at war with the Shang kingdom. Serving as a buffer zone against the Qiang, this frontier kingdom of Zhou shared much of the Shang’s material culture, such as its bronze work. In 1045 BCE, however, the Zhou noble family of Ji rebelled against and overthrew the Shang rulers at Anyang. In doing so, they laid the foundations for the Zhou dynasty, China’s third. In classical Chinese history, three key figures are involved in the overthrow of the Shang. They are King Wen, who originally expanded the Zhou realm, his son King Wu, who conquered the Shang, and King Wu’s brother, known as the duke of Zhou, who secured Zhou authority while serving as regent for King Wu’s heir. The deeds of these three men are recorded in China’s earliest transmitted text, The Book of Documents.The text portrays the Shang kings as corrupt and decadent, with the Zhou victory recorded as a result of their justice and virtue. The Zhou kings shifted the Shang system of religious worship away from Di, who was a personified supreme first ancestor figure and towards Tian, which was Heaven itself. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

The King's Power Dominating Society—A Re-Examination of Ancient Chinese

The King's Power Dominating Society—A Re-examination of Ancient Chinese Society Liu Zehua Abstract In terms of social formation, the most important characteristic of traditional Chinese society was how the king’s power dominated the society. Ever since the emergence of written records, we see that ancient China has had a most prominent interest group, that of the nobility and high officials, centered around the king (and later the emperor). Of all the kinds of power exerted on Chinese society, the king’s was the ultimate power. In the formation process of kingly power, a corresponding social structure was also formed. Not only did this central group include the king or emperor, the nobles, and the bureaucratic landlords, but the “feudal landlord ecosystem” which was formed within that group also shaped the whole society in a fundamental way. As a special form of economic redistribution, corruption among officials provided the soil for the growth of bureaucratic landlords. At the foundation of this entire bureaucratic web was always the king and his authority. In short, ancient Chinese society is a power-dependent structure centered on the king’s power. The major social conflict was therefore the conflict between the dictatorial king’s power and the rest of society. Keywords king’s power; landlord; social classes; despotism; social form Society of Imperial Power: Reinterpreting China’s “Feudal Society” Feng Tianyu 1 Abstract To call the period from Qin Dynasty to Qing Dynasty a “feudal society” is a misrepresentation of China’s historical reality. The fengjian system only occupied a secondary position in Chinese society from the time of Qin. -

The Transition of Inner Asian Groups in the Central Plain During the Sixteen Kingdoms Period and Northern Dynasties

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Fangyi Cheng University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cheng, Fangyi, "Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2781. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2781 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remaking Chineseness: The Transition Of Inner Asian Groups In The Central Plain During The Sixteen Kingdoms Period And Northern Dynasties Abstract This dissertation aims to examine the institutional transitions of the Inner Asian groups in the Central Plain during the Sixteen Kingdoms period and Northern Dynasties. Starting with an examination on the origin and development of Sinicization theory in the West and China, the first major chapter of this dissertation argues the Sinicization theory evolves in the intellectual history of modern times. This chapter, in one hand, offers a different explanation on the origin of the Sinicization theory in both China and the West, and their relationships. In the other hand, it incorporates Sinicization theory into the construction of the historical narrative of Chinese Nationality, and argues the theorization of Sinicization attempted by several scholars in the second half of 20th Century. The second and third major chapters build two case studies regarding the transition of the central and local institutions of the Inner Asian polities in the Central Plain, which are the succession system and the local administrative system. -

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China with a Focus on the Dao

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China With a focus on the Dao An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE By: Bryan Benson Ryan Coran Alberto Ramirez Date: 04/27/2017 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 4 Individual Participation 7 Authorship 8 1. Abstract 10 2. Introduction 11 3. Historical Background 12 3.1 Fall of Han dynasty/ Formation of the Three Kingdoms 12 3.2 Wu 13 3.3 Shu 14 3.4 Wei 16 3.5 Warfare and Relations between the Three Kingdoms 17 3.5.1 Wu and the South 17 3.5.2 Shu-Han 17 3.5.3 Wei and the Sima family 18 3.6 Weaponry: 18 3.6.1 Four traditional weapons (Qiang, Jian, Gun, Dao) 18 3.6.1.1 The Gun 18 3.6.1.2 The Qiang 19 3.6.1.3 The Jian 20 3.6.1.4 The Dao 21 3.7 Rise of the Empire of Western Jin 22 3.7.1 The Beginning of the Western Jin Empire 22 3.7.2 The Reign of Empress Jia 23 3.7.3 The End of the Western Jin Empire 23 3.7.4 Military Structure in the Western Jin 24 3.8 Period of Disunity 24 4. Materials and Manufacturing During the Period of Disunity 25 2 Table of Contents (Cont.) 4.1 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Han Dynasty 25 4.2 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Period of Disunity 26 5. -

Early Chinese Thought (Part 1) 1

Early Chinese Thought (part 1) 1. Fall of the Western Zhou 2. Eastern Zhou period 3. Changes in the nature of state and ruler 4. New social forces and rise of the shi 5. Expansion of Zhou cultural world Western Zhou aristocratic lineage system patrilineage dynasty Son of Heaven (tianzi) Eastward migration of Zhou court 771 BCE invaders Luo Zhou rong 戎 "invaders" Timeline of Zhou dynasty (1045 – 256 BCE) Bronze Age ca. 2000-600 BCE Western Zhou 1045 – 771 BCE Eastern Zhou Classical Period 770 – 256 BCE ca. 600-200 BCE Early Imperial Period ca. 200 BC-AD 600 1. Fall of the Western Zhou 2. Eastern Zhou period 3. Changes in the nature of state and ruler 4. New social forces and rise of the shi 5. Expansion of Zhou cultural world Timeline of Zhou dynasty (1045 – 256 BCE) Bronze Age ca. 2000-600 BCE Western Zhou 1045 – 771 BCE Eastern Zhou Spring and Autumn period Classical Period 770 – 256 BCE (Chunqiu 春秋), 770-403 BCE ca. 600-200 BCE Warring States period (Zhanguo 戰國), 403-221 BCE Early Imperial Period ca. 200 BCE-600 CE Spring and Autumn Annals Chunqiu 春秋 chronicle of the state of Lu, 722-481 BCE Intrigues of the Warring States Zhanguo ce 戰國策 entries for 454-221 BCE Zuo Chronicle Zuo Zhuan 左傳 commentary on Spring and Autumn Annals Duke of Jin 晉文公 Chong'er 重耳 (Double Ears) hegemon ba 霸 Major states of the Warring States Period 403-221 BCE ca. 400 BCE All-under-Heaven tianxia 天下 Qin 221 BCE Chariot burial Zhou Dynasty 1. -

The Warring States Period (453-221)

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 2.1 THE WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221) Introduction The Warring States period resembles the Spring and Autumn period in many ways. The multi-state structure of the Chinese cultural sphere continued as before, and most of the major states of the earlier period continued to play key roles. Warfare, as the name of the period implies, continued to be endemic, and the historical chronicles continue to read as a bewildering list of armed conflicts and shifting alliances. In fact, however, the Warring States period was one of dramatic social and political changes. Perhaps the most basic of these changes concerned the ways in which wars were fought. During the Spring and Autumn years, battles were conducted by small groups of chariot-driven patricians. Managing a two-wheeled vehicle over the often uncharted terrain of a battlefield while wielding bow and arrow or sword to deadly effect required years of training, and the number of men who were qualified to lead armies in this way was very limited. Each chariot was accompanied by a group of infantrymen, by rule seventy-two, but usually far fewer, probably closer to ten. Thus a large army in the field, with over a thousand chariots, might consist in total of ten or twenty thousand soldiers. With the population of the major states numbering several millions at this time, such a force could be raised with relative ease by the lords of such states. During the Warring States period, the situation was very different. -

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the Leader of the Zhou

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the leader of the Zhou (Chou), a subject people living in the west of the Chinese kingdom, overthrew the last king of the Shang Dynasty. King Wu died shortly after this victory, but his family, the Ji, would rule China for the next few centuries. Their dynasty is known as the Zhou Dynasty. The Mandate of Heaven After overthrowing the Shang Dynasty, the Zhou propagated a new concept known as the Mandate of Heaven. The Mandate of Heaven became the ideological basis of Zhou rule, and an important part of Chinese political philosophy for many centuries. The Mandate of Heaven explained why the Zhou kings had authority to rule China and why they were justified in deposing the Shang dynasty. The Mandate held that there could only be one legitimate ruler of China at one time, and that such a king reigned with the approval of heaven. A king could, however, loose the approval of heaven, which would result in that king being overthrown. Since the Shang kings had become immoral—because of their excessive drinking, luxuriant living, and cruelty— they had lost heaven’s approval of their rule. Thus the Zhou rebellion, according to the idea, took place with the approval of heaven, because heaven had removed supreme power from the Shang and bestowed it upon the Zhou. Western Zhou After his death, King Wu was succeeded by his son Cheng, but power remained in the hands of a regent, the Duke of Zhou. The Duke of Zhou defeated rebellions and established the Zhou Dynasty firmly in power at their capital of Fenghao on the Wei River (near modern-day Xi’an) in western China. -

Serfdom and Slavery 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SERFDOM AND SLAVERY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M L Bush | 9781317887485 | | | | | Serfdom and Slavery 1st edition PDF Book Thus, the manorial system exhibited a degree of reciprocity. In Early Modern France, French nobles nevertheless maintained a great number of seigneurial privileges over the free peasants that worked lands under their control. Villeins generally rented small homes, with a patch of land. German History. Hull Domesday Project. Encyclopedia of Human Rights: Vol. Cosimo, Inc. State serfs were emancipated in Why was the abbot so determined to keep William in prison? Book of Winchester. Clergy Knowledge worker Professor. With the growing profitability of industry , farmers wanted to move to towns to receive higher wages than those they could earn working in the fields, [ citation needed ] while landowners also invested in the more profitable industry. Admittedly, after that strong stance the explanation in the textbooks tends to get a bit hazy, and for good reason. Furthermore, the increasing use of money made tenant farming by serfs less profitable; for much less than it cost to support a serf, a lord could now hire workers who were more skilled and pay them in cash. The land reforms in northwestern Germany were driven by progressive governments and local elites [ citation needed ]. Hidden categories: Wikipedia articles incorporating a citation from the Encyclopaedia Britannica with Wikisource reference All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from December Articles with unsourced statements from June Wikipedia articles needing clarification from December All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from December Vague or ambiguous geographic scope from April Articles with unsourced statements from May Articles with unsourced statements from May In such a case he could strike a bargain with a lord of a manor. -

Spring and Autumn China (771-453)

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 1.7 SPRING AND AUTUMN CHINA (771-453) The history of the Spring and Autumn period was traditionally pictured as a narrative in which the major actors were states, their rulers, and certain high ministers and colorful figures. The narrative generally was shaped by writers to convey ethical points. It was, on the largest scale, a “true” story, but its drama was guided by a moral rationale. In these pages, we will survey the events of this long period. Our narrative will combine a selective recounting of major events with an attempt to illustrate the political variety that developed among the patrician states of the time. It embeds also certain stories from traditional sources, which are intended to help you picture more vividly and so recall more easily major turning points. These tales (which appear in italics) are retold here in a way that eliminates the profusion of personal and place names that characterize the original accounts. There are four such stories and each focuses on a single individual (although the last and longest has a larger cast of characters). The first two stories, those of Duke Huan of Qi and Duke Wen of Jin, highlight certain central features of Spring and Autumn political structures. The third tale, concerning King Ling of Chu, illustrates the nature of many early historical accounts as cautionary tales. The last, the story of Wu Zixu, is one of the great “historical romances” of the traditional annals. It is important to bear in mind that the tales recounted here are parts of a “master narrative” of early China, crafted by literary historians.