Quo Vadis Open-IX?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detecting Botnets Using File System Indicators

Detecting botnets using file system indicators Master's thesis University of Twente Author: Committee members: Peter Wagenaar Prof. Dr. Pieter H. Hartel Dr. Damiano Bolzoni Frank Bernaards LLM (NHTCU) December 12, 2012 Abstract Botnets, large groups of networked zombie computers under centralised control, are recognised as one of the major threats on the internet. There is a lot of research towards ways of detecting botnets, in particular towards detecting Command and Control servers. Most of the research is focused on trying to detect the commands that these servers send to the bots over the network. For this research, we have looked at botnets from a botmaster's perspective. First, we characterise several botnet enhancing techniques using three aspects: resilience, stealth and churn. We see that these enhancements are usually employed in the network communications between the C&C and the bots. This leads us to our second contribution: we propose a new botnet detection method based on the way C&C's are present on the file system. We define a set of file system based indicators and use them to search for C&C's in images of hard disks. We investigate how the aspects resilience, stealth and churn apply to each of the indicators and discuss countermeasures botmasters could take to evade detection. We validate our method by applying it to a test dataset of 94 disk images, 16 of which contain C&C installations, and show that low false positive and false negative ratio's can be achieved. Approaching the botnet detection problem from this angle is novel, which provides a basis for further research. -

Winter 2020 Colocation Services

2020 WINTER CUSTOMER SUCCESS REPORT COLOCATION SERVICES CATEGORY COLOCATION SERVICES OVERVIEW Colocation services allow businesses to host their data in a third-party data center that has privately-owned networking equipment and servers. Instead of maintaining servers in-house, at a private data center, or in offices, enterprises can elect to co-locate their infrastructure by renting space in a colocation center. Unlike other types of hosting where clients can rent server space owned by a hosting vendor, with colocation, the client owns the server and rents the physical space needed to house it in a data center. The colocation service rents out data center space where clients can install their equipment. It also provides the cooling, IP address, bandwidth, and power systems that the customer needs to deploy their servers. 2 Customer Success Report Ranking Methodology The FeaturedCustomers Customer Success ranking is based on data from our customer reference Customer Success Report platform, market presence, web presence, & social Award Levels presence as well as additional data aggregated from online sources and media properties. Our ranking engine applies an algorithm to all data collected to calculate the final Customer Success Report rankings. The overall Customer Success ranking is a weighted average based on 3 parts: Market Leader Content Score is affected by: Vendor on FeaturedCustomers.com with 1. Total # of vendor generated customer substantial customer base & market share. references (case studies, success stories, Leaders have the highest ratio of customer testimonials, and customer videos) success content, content quality score, and social media presence relative to company size. 2. Customer reference rating score 3. -

"SOLIZE India Technologies Private Limited" 56553102 .FABRIC 34354648 @Fentures B.V

Erkende referenten / Recognised sponsors Arbeid Regulier en Kennismigranten / Regular labour and Highly skilled migrants Naam bedrijf/organisatie Inschrijfnummer KvK Name company/organisation Registration number Chamber of Commerce "@1" special projects payroll B.V. 70880565 "SOLIZE India Technologies Private Limited" 56553102 .FABRIC 34354648 @Fentures B.V. 82701695 01-10 Architecten B.V. 24257403 100 Grams B.V. 69299544 10X Genomics B.V. 68933223 12Connect B.V. 20122308 180 Amsterdam BV 34117849 1908 Acquisition B.V. 60844868 2 Getthere Holding B.V. 30225996 20Face B.V. 69220085 21 Markets B.V. 59575417 247TailorSteel B.V. 9163645 24sessions.com B.V. 64312100 2525 Ventures B.V. 63661438 2-B Energy Holding 8156456 2M Engineering Limited 17172882 30MHz B.V. 61677817 360KAS B.V. 66831148 365Werk Contracting B.V. 67524524 3D Hubs B.V. 57883424 3DUniversum B.V. 60891831 3esi Netherlands B.V. 71974210 3M Nederland B.V. 28020725 3P Project Services B.V. 20132450 4DotNet B.V. 4079637 4People Zuid B.V. 50131907 4PS Development B.V. 55280404 4WEB EU B.V. 59251778 50five B.V. 66605938 5CA B.V. 30277579 5Hands Metaal B.V. 56889143 72andSunny NL B.V. 34257945 83Design Inc. Europe Representative Office 66864844 A. Hak Drillcon B.V. 30276754 A.A.B. International B.V. 30148836 A.C.E. Ingenieurs en Adviesbureau, Werktuigbouw en Electrotechniek B.V. 17071306 A.M. Best (EU) Rating Services B.V. 71592717 A.M.P.C. Associated Medical Project Consultants B.V. 11023272 A.N.T. International B.V. 6089432 A.S. Watson (Health & Beauty Continental Europe) B.V. 31035585 A.T. Kearney B.V. -

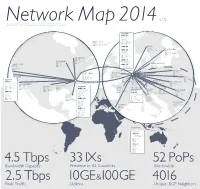

Network Map 2014 Leaseweb Master V1.5

v.1.5 NeThis network is owned and operated by FiberRing B.tV. FiberRing wois a sister company of LeaseWeb, which togetherr with DataXenkter Map 2014 and EvoSwitch constitute the OCOM Group. Please visit the legal section of the LeaseWeb website for more detailed information DATA CENTERS: AMS-01 J.W. Lucasweg 35, 2031BE Haarlem PoP AMS - 01 PNI 200 Gbps PoP Point of Presence IXP 200 Gbps AMS-IX PNI Private Network Interconnection IXP 20 Gbps NL-IX IXP Internet Exchange Point BGP 624 BGP Border Gateway Protocol AMS-02 OSLO s p 2015 Expansion Plan b PoP OSL -10 G PNI 0 Gbps 1 s STOCKHOLM AMS-10 IXP 1 Gbps NIX.NO bp G PoP STO-10 Kuiperbergweg 13, BGP 22 20 1101AE Zuidoost PNI 1 0 Gbps IXP 20 Gbps NETNOD PoP AMS -10 BGP 61 PNI 160 Gbps IXP 100 Gbps AMS-IX TORONTO BGP 473 PoP T OR -10 PNI 0 Gbps AMS-11 Boeing Avenue 271, CHICAGO IXP 1 0 Gbps TORIX 1119PD Schiphol-Rijk PoP CHI -10 BGP 54 1 COPENHAGEN PNI 0 s 0 Gbps 1 p b PALO ALTO G 0 AMS-12 G PoP C PH -10 IXP 10 Gbps Equinix b 1 PoP SFO -10 p G 30 Gbps Capronilaan 2, s b PNI 0 Gbps BGP 45 PNI 20 Gbps p 1119NR Schiphol-Rijk s IXP 1 Gbps DIX IXP 10 Gbps Equinix BGP 22 BGP 118 AMSTERDAM 30 Gbps WARSAW PoP WAR -10 s p LONDON 140 Gbps DÜSSELDORF PNI 30 Gbps 10 G b NEW YORK 20 Gbp bps G PoP LON -10 PoP DUS -10 IXP 20 Gbps PLIX s 0 PoP NYC -10 3 PNI 40 Gbps PNI 40 Gbps 10 Gbps PNI 30 Gbps BGP 218 IXP 60 Gbps LINX 40 G IXP 20 Gbps ECIX SAN JOSÉ IXP 10 Gbps Equinix bps KIEV BGP 350 BGP 84 IXP 10 Gbps NYIIX BRUSSELS PoP KBP-10 PoP BRU -10 DATA CENTER: BGP 154 PNI 10 Gbps PNI 1 Gbps 1 Gb IXP 10Gbps DTEL 10 Gbps 2 PRAGUE ps SFO -11 bps IXP 20 Gbps BNIX LUXEMBOURG 0 G BGP 44 11 Great Oaks Blvd 60 G 2 bps PoP PRA-10 BRATISLAVA ps BGP 35 PoP LUX -10 00 10 Gb bps WASHINGTON D.C. -

Child Abuse Images and Cleanfeeds: Assessing Internet Blocking Systems

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Child Abuse Images and Cleanfeeds: Assessing Internet Blocking Systems Authors(s) McIntyre, T.J. Publication date 2013 Publication information Brown, I. (eds.). Research Handbook on Governance of the Internet Publisher Edward Elgar Link to online version www.e-elgar.com/shop/research-handbook-on-governance-of-the-internet Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/7594 Publisher's statement Edward Elgar Publishing is the source and copyright holder of the work, and the article cannot be used for any other purpose elsewhere. The chapter is for private use only. Downloaded 2020-01-30T19:55:05Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Child Abuse Images and Cleanfeeds: Assessing Internet Blocking Systems 1 Child Abuse images and Cleanfeeds: Assessing Internet Blocking Systems TJ McIntyre1 School of Law, University College Dublin [email protected] To appear in: Ian Brown, ed., Research Handbook on Governance of the Internet (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, forthcoming) 1. Introduction One of the most important trends in internet governance in recent years has been the growth of internet blocking as a policy tool, to the point where it is increasingly becoming a global norm. This is most obvious in states such as China where blocking is used to suppress political speech; however, in the last decade blocking has also become more common in democracies, usually as part of attempts to limit the availability of child abuse images. -

The Phoenix Market Special Report

Special Report The Phoenix Market Written by Rich Miller Photo courtesy Data Center Frontier A view of the mountains in Mesa, Arizona, as seen from the Elliott Road Technology Corridor. brought to you by © 2021 Data Center Frontier Phoenix Market SPECIAL REPORT Contents Introduction................................................ 2 CyrusOne ................................................ 8 About Data Center Frontier ........................... 2 Cyxtera .................................................. 9 About datacenterHawk ................................ 2 DataBank (zColo) ........................................ 9 Market Overview & Analysis .............................. 3 Digital Realty ..........................................10 What’s Hot About Phoenix? ............................ 4 EdgeConneX ............................................10 Trends in Demand ....................................... 5 EdgeCore ...............................................11 Trends in Supply ......................................... 6 Flexential ..............................................11 Business Environment .................................... 7 H5 Data Centers ........................................11 Connectivity ............................................. 7 INAP .....................................................12 Power ..................................................... 7 Iron Mountain Data Centers .........................12 Hazard Risk Overview .................................. 7 PhoenixNAP ............................................12 -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Annual Report 2011 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Annual Report 2011 About the Association 4 Profile 4 Mission 4 Foreword by the Chairman of the Board 5 Foreword by the Director of the Association 6 Members in 2011 8 Changes in 2011 8 List of members as of 31st December 2011 9 Customers in 2011 10 Changes in 2011 10 List of customers as of 31st December 2011 10 List of TLD customers as of 31st December 2011 10 Statutory Bodies in 2011 11 Board of Directors 11 Table of Supervisory Board 11 Presentation 12 History 12 Contents Main events of 2011 13 Development of connected ports 14 Technical solution 15 Topology 15 Employees in 2011 16 Financial Data 18 Balance sheet 19 Profit and loss statement 20 Independent Auditor’s Report 21 Strategic goals for 2012 22 Registered Office and Contact Details 23 Annual Report 2011 3 About the Association Profile NIX.CZ, z.s.p.o. (Professional Association of Legal Entities) is a company associating Czech and foreign Internet related businesses in order to mutually interconnect their networks (so called peering). The Association was founded on 1st October 1996 by eight companies. The main reason for establishing the association was to simplify the system of interconnecting individual Internet networks and to save resources associated with such interconnections. At present, NIX.CZ associates 83 members and 25 customers and its maximum data traffic exceeds the amount of 200 Gbps. The Association provides stable and reliable exchange of approximately two thirds of all data flow within the Czech Republic. -

Pdf / Companies in Grey Were Spotted in the Herbivore Packet Analysis

COMPANIES USAGE TYPE DESCRIPTION WEBSITE A.C. Nielsen Company (COM) Commercial global marketing research firm http://www.nielsen.com/us/en.html ADForm A/S (COMP) Company/T1 global digital media advertising technology company. Based in Copenhagen http://site.adform.com/ American multinational computer software company. The company is Adobe Systems Inc. (COM) Commercial headquartered in San Jose, California, United States. http://www.adobe.com/about-adobe.html CLOUD/ leading content delivery network (CDN) services provider for media Akamai Technologies Inc. (CDN) Content Delivery Network and software delivery, and cloud security solutions. https://www.akamai.com/ Amazon Technologies, Inc. operates as a subsidiary of Amazon.com Inc. Amazon Technologies Inc. (DCH) Data Center/Web Hosting/Transit Engaged in the provision of services for engineering projects, and environmental feasibility and techno-economic studies. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_(company) Amazon.com, Inc., doing business as Amazon, is an American electronic Amazon.com Inc. (DCH) Data Center/Web Hosting/Transit commerce and cloud computing company based in Seattle, Washington that was founded by Jeff Bezos on July 5, 1994. https://www.amazon.com/p/feature/rzekmvyjojcp6uc AOL is a web portal and online service provider based in New York. It is a AOL Inc. (ISP) Fixed Line ISP brand marketed by Oath, a subsidiary of Verizon Communications. https://www.aol.com/ American multinational technology company headquartered in Cupertino, Apple Inc. (COM) Commercial California that designs, develops, and sells consumer electronics, computer software, and online services. https://www.apple.com/sitemap/ internet technology company that powers the real-time sale and purchase of Appnexus Inc (COM) Commercial digital advertising https://www.appnexus.com/en Content delivery network, DDoS mitigation, Internet security services and CloudFlare Inc. -

Dutch Data Centers

2016 State of the Dutch Data Centers The new foundation 2 | © 2016 Dutch Datacenter Association Dutch Data Center Report 2016 State of the Dutch Data Centers The new foundation © 2016 Dutch Datacenter Association | 3 COLOPHON The Dutch Data Center Report 2016: State of the Dutch Data Centers is published by the Dutch Datacenter Association. Edition Editor-in-Chief State of the Dutch Data Centers 2016: Stijn Grove June 2016, year 2 Managing Director Dutch Datacenter Association Contributions Dutch Datacenter Association (Stijn Grove, Noor van den Marketing & artwork Bogaard, Luuk ter Weeme) Noor van den Bogaard (DDA) PB7 Research (Peter Vermeulen) Michiel Cazemier, Gaby Dam, CBRE Data Centre Solutions (Mitul Patel) Wouter Pegtel (Splend) Research by Print quantity Peter Vermeulen First release, 14 Jun 2016: 100 Principal Analyst PB7 Availability Our publications are free to download on Mitul Patel www.dutchdatacenters.nl Associate Director CBRE DDA thanks all people who made this report possible. A special thanks to Simon Besteman, Micky van Vollenhoven and Marc Gauw. © 2016 Dutch Datacenter Association TERMS OF USE AND DISCLAIMER The Dutch Data Center Report 2016: State of the Dutch Data Centers (iii) accept no liability for any use of the said Data or reliance placed on it, (herein: “Report”) presents information and data that were compiled and/ in particular, for any interpretation, decisions, or actions based on the Data or collected by the Dutch Datacenter Association (all information and data in this Report. referred herein as “Data”). Data in this Report is subject to change without notice. Other parties may have ownership interests in some of the Data contained in this Report. -

I-Root-Src-Analysis 2013.Key

www.netnod.se I.ROOT-SERVERS.NET Analysis of Query SRC and Anycast locations 2013 version! APRICOT2013, Singapore, Kurt Erik Lindqvist ([email protected]) www.netnod.se i.root-servers.net One of thirteen DNS root-servers Operated by non-profit Netnod in Stockholm, SE (also operates the Internet Exchanges) Anycast at +40 locations around the world APRICOT2013, Singapore, Kurt Erik Lindqvist ([email protected]) www.netnod.se The root-servers APRICOT2013, Singapore, Kurt Erik Lindqvist ([email protected]) Source: www.root-servers.org www.netnod.se The root-servers All have different hardware / software architecture, choices etc. Diversity is Good! All have different deployment strategies •Some are unicast, some are anycast •Some are anycast at IXPs some are inside carrier networks •Some have few global nodes, and the rest are local nodes APRICOT2013, Singapore, Kurt Erik Lindqvist ([email protected]) www.netnod.se i.root deployments Most locations are at IXPs, a few inside Tier-1 networks, a few locations are where no IXP exists Global / local distinction per peer (using no-export) Most peers are local APRICOT2013, Singapore, Kurt Erik Lindqvist ([email protected]) www.netnod.se i.root-servers.net APRICOT2013, Singapore, Kurt Erik Lindqvist ([email protected]) www.netnod.se Peerings Approx. +3000 peerings with approx 650 ASNs Incudes route-servers at some of the larger IXPs We are always looking for more peerings! [email protected] http://as8674.peeringdb.com APRICOT2013, Singapore, Kurt Erik Lindqvist ([email protected]) www.netnod.se Analysis -

Leaseweb Schakelt Snel Met Bandbreedte En Apparatuur

LeaseWeb schakelt snel met bandbreedte en apparatuur Professionele hosting LeaseWeb levert diensten zoals colocatie, dedicated servers, server virtualisatie, streaming, webhosting en domeinnaam registratie. Onze engineers zorgen 24x7 voor kennisintensieve support. groeikracht LeaseWeb heeft de filosofie om altijd twee keer zoveel bandbreedtecapaciteit in het hostingnetwerk aan te houden als klanten verbruiken. Ook binnen onze datacenteromgeving hebben wij veel groeimogelijkheden. Daarnaast hebben wij standaard veel apparatuur op voorraad. Hiermee is uw webomgeving altijd verzekerd van hosting met groeikracht. scherPe Prijs Wij bieden hoge kwaliteit hostingoplossingen tegen zeer scherpe prijzen. Om die reden zijn de producten van LeaseWeb aantrekkelijk voor eindgebruikers, maar ook voor resellers en internetprofessionals die complexe hostingoplossingen in de markt zetten. Ons continue streven naar “LeaseWeb heeft ons schaalvergroting zorgt ervoor dat wij die scherpe prijzen ook in de toekomst kunnen waarmaken. een prachtige groene hostingoplossing groene hosting LeaseWeb heeft 2.000 racks beschikbaar in CO2-neutraal datacenter geboden. Wij hebben EvoSwitch (www.evoswitch.com). Dit ‘next generation’ datacenter is het ook voor LeaseWeb eerste datacenter in Nederland dat energiezuinig en volledig klimaatneutraal gekozen omdat zij ruime opereert. LeaseWeb kan er dus voor zorgen dat uw hostingomgeving volledig ‘groen’ wordt ingericht. ervaring hebben op het gebied van Microsoft, Als klant van LeaseWeb kunt u het label Linux en VMware.” The Green Fan (www.thegreenfan.com) op uw website plaatsen, om de maatschappij te EdWin van VOOrbErGEn laten zien dat u investeert in terugdringing Projectmanager ICT van de CO2-uitstoot. bij Joh. Enschedé IT & Consultancy MEER WETEN? Heeft u interesse in de hostingdiensten van LeaseWeb, kijk dan op www.leaseweb.nl. -

Leading Hosting Provider Required Innovative Advanced Server Load Balancing Solution

CASE STUDY Leading Hosting Provider Required Innovative Advanced Server Load Balancing Solution Company: • LeaseWeb Our internal test procedures proved A10 products performed up to and Industry: “ above our requirements. We have installed many A10 appliances and we • Service Provider plan to implement more once the need arises. Critical Issues: “ Bastiaan Spandaw, • Hosting provider required high performing Lead Architect, advanced SLB solution with no licensing LeaseWeb fees and a plethora of features to satisfy customizable customer solutions. Selection Criteria: Introduction • Performance test results surpassed LeaseWeb is a growing provider of hosted infrastructure solutions, which include a expectations and all-inclusive feature set portfolio that spans from traditional dedicated server hosting to cloud and colocation model. solutions, or hybrid solutions. As a prominent subsidiary of Ocom Group, LeaseWeb Benefits: has been offering world class hosting solutions that support mission critical websites, • Easy Adoption Internet applications, email servers, security and storage services since 1997. In addition • Greener Choice to a network uptime of 99.999%, LeaseWeb currently offers its customers an available • Improved Security bandwidth of more than 2.3 Tbps. LeaseWeb currently hosts some of the largest and most • Feature Rich respected enterprises in Europe and in North America, spanning six data centers across the • No Licensing Netherlands, Germany and the United States. Similar to A10 Networks® “Customer Driven Results: Innovation”, LeaseWeb has a customer focused philosophy, which centers on commitment to customers of all sizes, from the very smallest user to the largest global customer, with • Proven reliability and flexibility to provide LeaseWeb with exclusive customer industry surpassing customer service. requirements in addition to excellent Advanced Server Load Balancing Solution with No Licensing Fees customer support.