Classification of the Most Luminous Compact 8 Μm Sources in the Large Magellanic Cloud Joel H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1612.03165V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 12 Sep 2017 – 2 –](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0040/arxiv-1612-03165v3-astro-ph-he-12-sep-2017-2-20040.webp)

Arxiv:1612.03165V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 12 Sep 2017 – 2 –

The second catalog of flaring gamma-ray sources from the Fermi All-sky Variability Analysis S. Abdollahi1, M. Ackermann2, M. Ajello3;4, A. Albert5, L. Baldini6, J. Ballet7, G. Barbiellini8;9, D. Bastieri10;11, J. Becerra Gonzalez12;13, R. Bellazzini14, E. Bissaldi15, R. D. Blandford16, E. D. Bloom16, R. Bonino17;18, E. Bottacini16, J. Bregeon19, P. Bruel20, R. Buehler2;21, S. Buson12;22, R. A. Cameron16, M. Caragiulo23;15, P. A. Caraveo24, E. Cavazzuti25, C. Cecchi26;27, A. Chekhtman28, C. C. Cheung29, G. Chiaro11, S. Ciprini25;26, J. Conrad30;31;32, D. Costantin11, F. Costanza15, S. Cutini25;26, F. D'Ammando33;34, F. de Palma15;35, A. Desai3, R. Desiante17;36, S. W. Digel16, N. Di Lalla6, M. Di Mauro16, L. Di Venere23;15, B. Donaggio10, P. S. Drell16, C. Favuzzi23;15, S. J. Fegan20, E. C. Ferrara12, W. B. Focke16, A. Franckowiak2, Y. Fukazawa1, S. Funk37, P. Fusco23;15, F. Gargano15, D. Gasparrini25;26, N. Giglietto23;15, M. Giomi2;59, F. Giordano23;15, M. Giroletti33, T. Glanzman16, D. Green13;12, I. A. Grenier7, J. E. Grove29, L. Guillemot38;39, S. Guiriec12;22, E. Hays12, D. Horan20, T. Jogler40, G. J´ohannesson41, A. S. Johnson16, D. Kocevski12;42, M. Kuss14, G. La Mura11, S. Larsson43;31, L. Latronico17, J. Li44, F. Longo8;9, F. Loparco23;15, M. N. Lovellette29, P. Lubrano26, J. D. Magill13, S. Maldera17, A. Manfreda6, M. Mayer2, M. N. Mazziotta15, P. F. Michelson16, W. Mitthumsiri45, T. Mizuno46, M. E. Monzani16, A. Morselli47, I. V. Moskalenko16, M. Negro17;18, E. Nuss19, T. Ohsugi46, N. Omodei16, M. Orienti33, E. -

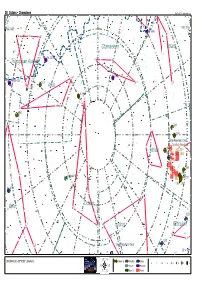

Skytools Chart

38 Octans - Chamaleon SkyTools 3 / Skyhound.com β NGC 6025 NGC 2516 IC 2448 β β ε γ Chamaeleon Volans δ ε ε PK 315-13.1 Triangulum Australe β γ 12h δ2 α ε 3195 ζ PK 325-12.1 1 α ζ 6101 5h η θ δ α Apus 09h 2 IC 4499 γ δ1 β γ ζ 6362 η 2 2210 η 2164 18h 06h Large Magellanic Cloud Tarantula Nebulaδ Mensa 2031 NGC 2014 NGC 1962 NGC 1955 ζ NGC 1874 NGC 1829 θ 1866 κ NGC 1770 1805 Collinder 411 NGC 1814 1978 1818 1783 03h 6744 21h β ε ε γ Octans Pavo ν -80° 00h ν 1559 β α δ θ Hydrus Reticulum β γ ι δ 1313 β Small Magellanic Cloud 0° 52° x 34° -7 ε ζ κ 00h00m00.0s -90°00'00" (Skymark) Globular Cl. Dark Neb. Galaxy 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Globule Planetary Open Cl. Nebula 38 Octans - Chamaleon GALASSIE Sigla Nome Cost. A.R. Dec. Mv. Dim. Tipo Distanza 200/4 80/11,5 20x60 NGC 292 Small Magellanic Cloud Tuc 00h 52m 38s +72° 48' 01” +2,80 318',0x204',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1313 Ret 03h 18m 15s -66° 29' 51” +9,70 9',5x7',2 Sbcd 13,5 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1559 Ret 04h 17m 36s -62° 47' 01" +11,00 4',2x2',1 SBc 34,0 Mly --- --- --- PGC 17223 Large Magellanic Cloud Dor 05h 23m 35s -69° 45' 22" +0,80 648',0x552',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 6744 Pav 19h 09m 46s -63° 51' 28" +9,10 17',0x10',7 SABb 21,0 Mly --- --- --- AMMASSI APERTI Sigla Nome Cost. -

The Luminosities of Cool Supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds, and the Humphreys-Davidson Limit Revisited

This is a repository copy of The luminosities of cool supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds, and the Humphreys-Davidson limit revisited. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/130065/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Davies, B., Crowther, P.A. and Beasor, E.R. (2018) The luminosities of cool supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds, and the Humphreys-Davidson limit revisited. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 478 (3). pp. 3138-3148. ISSN 0035-8711 https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty1302 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society following peer review. The version of record Ben Davies, Paul A Crowther, Emma R Beasor, The luminosities of cool supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds, and the Humphreys–Davidson limit revisited, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 478, Issue 3, August 2018, Pages 3138–3148, is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty1302 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

The Messenger

THE MESSENGER No, 40 - June 1985 Radial Veloeities of Stars in Globular Clusters: a Look into CD Cen and 47 Tue M. Mayor and G. Meylan, Geneva Observatory, Switzerland Subjected to dynamical investigations since the beginning photometry of several clusters reveals a cusp in the luminosity of the century, globular clusters still provide astrophysicists function of the central region, which could be the first evidence with theoretical and observational problems, wh ich so far have for collapsed cores. only been partly solved. The development of photoelectric cross-corelation tech If for a long time the star density projected on the sky was niques for the determination of stellar radial velocities opened fairly weil represented by simple dynamical models, recent the door to kinematical investigations (Gunn and Griffin, 1979, N .~- .", '. '.'., .' 1 '&307 w E ,. 1~ S Fig. 1: Left: 47 Tue (NGC 104) from the Deep Blue Survey - SRC-(J). Right: Centre of 47 Tue from a near-infrared photometrie study of Lioyd Evans. The diameter ofthe large eirele eorresponds to the disk ofthe left photograph. The maximum ofthe rotation appears inside the eircle; the linear part of the rotation eurve (solid-body rotation) affeets only stars inside one areminute of the eentre. 1 Rlre J 250r;.' .;r2' -i4.:...__.....;6;.;.. .;rB. ,;.;10::....--. Tentative Time-table of Council Sessions (J lkm/5] and Committee Meetings in 1985 (.) Gen x =2. November 12 Scientific Technical Committee November 13-14 Finance Committee December 11 -12 Observing Programmes Committee December 16 Committee of Council December 17 Council 10. All meetings will take place at ESO in Garching. -

407 a Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , 351–353 Achromat

Index A Barnard 72 , 210–211 Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , Barnard, E.E. , 5, 389 351–353 Barnard’s loop , 5–8 Achromat , 365 Barred-ring spiral galaxy , 235 Adaptive optics (AO) , 377, 378 Barred spiral galaxy , 146, 263, 295, 345, 354 AGC S 373. See Abell Galaxy Cluster Bean Nebulae , 303–305 S 373 (AGC S 373) Bernes 145 , 132, 138, 139 Alnitak , 11 Bernes 157 , 224–226 Alpha Centauri , 129, 151 Beta Centauri , 134, 156 Angular diameter , 364 Beta Chamaeleontis , 269, 275 Antares , 129, 169, 195, 230 Beta Crucis , 137 Anteater Nebula , 184, 222–226 Beta Orionis , 18 Antennae galaxies , 114–115 Bias frames , 393, 398 Antlia , 104, 108, 116 Binning , 391, 392, 398, 404 Apochromat , 365 Black Arrow Cluster , 73, 93, 94 Apus , 240, 248 Blue Straggler Cluster , 169, 170 Aquarius , 339, 342 Bok, B. , 151 Ara , 163, 169, 181, 230 Bok Globules , 98, 216, 269 Arcminutes (arcmins) , 288, 383, 384 Box Nebula , 132, 147, 149 Arcseconds (arcsecs) , 364, 370, 371, 397 Bug Nebula , 184, 190, 192 Arditti, D. , 382 Butterfl y Cluster , 184, 204–205 Arp 245 , 105–106 Bypass (VSNR) , 34, 38, 42–44 AstroArt , 396, 406 Autoguider , 370, 371, 376, 377, 388, 389, 396 Autoguiding , 370, 376–378, 380, 388, 389 C Caldwell Catalogue , 241 Calibration frames , 392–394, 396, B 398–399 B 257 , 198 Camera cool down , 386–387 Barnard 33 , 11–14 Campbell, C.T. , 151 Barnard 47 , 195–197 Canes Venatici , 357 Barnard 51 , 195–197 Canis Major , 4, 17, 21 S. Chadwick and I. Cooper, Imaging the Southern Sky: An Amateur Astronomer’s Guide, 407 Patrick Moore’s Practical -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

![Arxiv:1802.01597V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 5 Feb 2018 Born 1991)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6522/arxiv-1802-01597v1-astro-ph-ga-5-feb-2018-born-1991-1726522.webp)

Arxiv:1802.01597V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 5 Feb 2018 Born 1991)

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. AA_2017_32084 c ESO 2018 February 7, 2018 Mapping the core of the Tarantula Nebula with VLT-MUSE? I. Spectral and nebular content around R136 N. Castro1, P. A. Crowther2, C. J. Evans3, J. Mackey4, N. Castro-Rodriguez5; 6; 7, J. S. Vink8, J. Melnick9 and F. Selman9 1 Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, 1085 S. University Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1107, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Hounsfield Road, Sheffield, S3 7RH, UK 3 UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh, EH9 3HJ, UK 4 Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 31 Fitzwilliam Place, Dublin, Ireland 5 GRANTECAN S. A., E-38712, Breña Baja, La Palma, Spain 6 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, E-38205 La Laguna, Spain 7 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, E-38205 La Laguna, Spain 8 Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, Northern Ireland, UK 9 European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Cordova 3107, Santiago, Chile February 7, 2018 ABSTRACT We introduce VLT-MUSE observations of the central 20 × 20 (30 × 30 pc) of the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud. The observations provide an unprecedented spectroscopic census of the massive stars and ionised gas in the vicinity of R136, the young, dense star cluster located in NGC 2070, at the heart of the richest star-forming region in the Local Group. Spectrophotometry and radial-velocity estimates of the nebular gas (superimposed on the stellar spectra) are provided for 2255 point sources extracted from the MUSE datacubes, and we present estimates of stellar radial velocities for 270 early-type stars (finding an average systemic velocity of 271 ± 41 km s−1). -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

Giant Stellar Arcs in the Large Magellanic Cloud: a Possible Link with Past Activity of the Milky Way Nucleus

Giant stellar arcs in the Large Magellanic Cloud: a possible link with past activity of the Milky Way nucleus Yuri N. Efremov* Sternberg Astronomical Institute of the Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow 119992, Russia Accepted 2012 November 1. Received 2012 November 1; in original form 2012 September 7 ABSTRACT The origin of the giant stellar arcs in the LMC remains a controversial issue, discussed since 1966. No other star/cluster arc is so perfect a segment of a circle; moreover, there is another similar arc near-by. Many hypotheses were advanced to explain these arcs, and all but one of these were disproved. It was proposed in 2004 that origin of these arcs was due to the bow shock from the jet, which is intermittently fired by the Milky Way nucleus – and during the last episode of its activity the jet was pointed to the LMC. Quite recently evidence for such a jet has really appeared. We suppose it was once energetic enough to trigger star formation in the LMC, and if the jet opening angle was about 2°, it could push out HI gas from the region of about 2 kpc in size, forming a cavity LMC4, - but also squeezed two dense clouds, which occurred in the same area, causing the formation of stars along their surfaces facing the core of the MW. In result, spherical segments of the stellar shells might arise, visible now as the arcs of Quadrant and Sextant, the apices of which point to the center of the MW. This orientation of both arcs can be the key to unlocking their origin. -

An Empirical Formula for the Mass-Loss Rates of Dust-Enshrouded

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 2555text July 29, 2018 (DOI: will be inserted by hand later) An empirical formula for the mass-loss rates of dust-enshrouded red supergiants and oxygen-rich Asymptotic Giant Branch stars⋆ Jacco Th. van Loon1, Maria-Rosa L. Cioni2,3, Albert A. Zijlstra4, Cecile Loup5 1 Astrophysics Group, School of Physical & Geographical Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire ST5 5BG, UK 2 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild Straße 2, D-85748 Garching bei M¨unchen, Germany 3 Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ, UK 4 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, Sackville Street, P.O.Box 88, Manchester M60 1QD, UK 5 Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 98bis Boulevard Arago, F-75014 Paris, France Received date; Accepted date Abstract. We present an empirical determination of the mass-loss rate as a function of stellar luminosity and effective temperature, for oxygen-rich dust-enshrouded Asymptotic Giant Branch stars and red supergiants. To this aim we obtained optical spectra of a sample of dust-enshrouded red giants in the Large Magellanic Cloud, which we complemented with spectroscopic and infrared photometric data from the literature. Two of these turned out to be hot emission-line stars, of which one is a definite B[e] star. The mass-loss rates were measured through modelling of the spectral energy distributions. We thus obtain the mass-loss rate formula log M˙ = −5.65 + 1.05 log(L/10, 000 L⊙) − 6.3 log(Teff /3500 K), valid for dust-enshrouded red supergiants and oxygen-rich AGB stars. -

Spitzer Analysis of HII Region Complexes in the Magellanic

DRAFT VERSION AUGUST 16, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 04/20/08 SPITZER ANALYSIS OF H II REGION COMPLEXES IN THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS: DETERMINING A SUITABLE MONOCHROMATIC OBSCURED STAR FORMATION INDICATOR B. LAWTON1,K.D.GORDON1,B.BABLER2,M.BLOCK3,A.D.BOLATTO4,S.BRACKER2,L.R.CARLSON5,C.W.ENGELBRACHT3, J. L. HORA6,R.INDEBETOUW7,S.C.MADDEN8,M.MEADE2,M.MEIXNER1,K.MISSELT3,M.S.OEY9,J.M.OLIVEIRA10, T. ROBITAILLE6,M.SEWILO1,B.SHIAO1 U. P. VIJH11 , AND B. WHITNEY12 Draft version August 16, 2018 ABSTRACT H II regionsare the birth places of stars, and as such they providethe best measure of current star formation rates (SFRs) in galaxies. The close proximity of the Magellanic Clouds allows us to probe the nature of these star forming regions at small spatial scales. To study the H II regions, we compute the bolometric infrared flux, or total infrared (TIR), by integrating the flux from 8 to 500 µm. The TIR provides a measure of the obscured star formation because the UV photons from hot young stars are absorbed by dust and re-emitted across the mid-to-far-infrared(IR) spectrum. We aim to determine the monochromatic IR band that most accurately traces the TIR and produces an accurate obscured SFR over large spatial scales. We present the spatial analysis, via aperture/annulusphotometry, of 16 Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and 16 Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) H II region complexes using the Spitzer Space Telescope’s IRAC (3.6, 4.5, 8 µm) and MIPS (24,70, 160 µm) bands. -

The Luminosities of Cool Supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds, and the Humphreys-Davidson Limit Revisited

MNRAS 000, 1–10 (2017) Preprint 19 April 2018 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The luminosities of cool supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds, and the Humphreys-Davidson limit revisited Ben Davies,1?, Paul A. Crowther2 and Emma R. Beasor1 1Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool Science Park ic2, 146 Brownlow Hill, Liverpool, L3 5RF, UK 2Dept of Physics & Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Hounsfield Rd, Sheffield S3 7RH, UK Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT The empirical upper luminosity boundary Lmax of cool supergiants, often referred to as the Humphreys-Davidson limit, is thought to encode information on the general mass-loss be- haviour of massive stars. Further, it delineates the boundary at which single stars will end their lives stripped of their hydrogen-rich envelope, which in turn is a key factor in the rela- tive rates of Type-II to Type-Ibc supernovae from single star channels. In this paper we have revisited the issue of Lmax by studying the luminosity distributions of cool supergiants (SGs) in the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds (LMC/SMC). We assemble samples of cool SGs in each galaxy which are highly-complete above log L/L =5.0, and determine their spectral energy distributions from the optical to the mid-infrared using modern multi-wavelength sur- vey data. We show that in both cases Lmax appears to be lower than previously quoted, and is in the region of log L/L =5.5. There is no evidence for Lmax being higher in the SMC than in the LMC, as would be expected if metallicity-dependent winds were the dominant factor in the stripping of stellar envelopes.