Open Clusters PAGING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

References and for Further Reading

Contents Preface. vii Acknowledgements. ix About the Author . xi Chapter 1 A Short History of Planetary Nebulae. 1 Further Discoveries. 1 The Nature of the Nebulae and Modern Catalogues . 3 Chapter 2 The Evolution of Planetary Nebulae . 7 The Lives of the Stars . 7 Stages in the Life Cycle of a Sun-like Star . 9 The Asymptotic Giant Branch . 10 Proto-Planetary Nebulae and Dust. 12 Interactive Winds. 13 Emissions from Planetary Nebulae. 14 Central Stars. 16 Planetary Envelopes . 17 Binary Stars and Magnetic Fields . 19 Lifetimes of Planetary Nebulae . 21 Conclusion . 21 Chapter 3 Observing Planetary Nebulae . 23 Telescopes and Mountings . 23 Telescope Mounts. 26 Eyepieces. 27 Limiting Magnitudes and Angular Resolution . 29 Transparency and Seeing . 31 Dark Adaptation and Averted Vision . 32 Morphology of Planetary Nebulae . 33 Nebular Filters . 35 Star Charts, Observing and Computer Programs. 38 Observing Procedures. 42 Chapter 4 Photographing Planetary Nebulae. 45 Camera Equipment . 45 Software. 48 Filters for Astrophotography . 49 Contents Shooting . 50 Conclusion . 53 xiii Chapter 5 Planetary Nebulae Catalogues . 55 Main Planetary Nebulae . 56 Additional Planetary Nebulae . 58 Chapter 6 Planetary Nebulae by Constellation. 81 Andromeda. 83 Apus. 85 Aquarius . 87 Aquila . 90 Ara . 103 Auriga . 106 Camelopardalis . 108 Canis Major . 111 Carina . 113 Cassiopeia . 119 Centaurus . 123 Cepheus. 126 Cetus . 129 Chameleon . 131 Corona Australis . 133 Corvus. 135 Cygnus. 137 Delphinus . 154 Draco . 157 Eridanus . 160 Fornax . 162 Gemini. 164 Hercules . 170 Hydra. 174 Lacerta. 178 Leo . 180 Lepus . 182 Lupus . 184 Lynx . 190 Lyra . 192 Monoceros . 195 Musca. 198 Norma . 203 Ophiuchus. 205 Orion . 211 Pegasus . 214 Perseus. 219 Puppis . -

Portrait of a Dramatic Stellar Crib 21 December 2006

Portrait of a dramatic stellar crib 21 December 2006 most massive stars known. The nebula owes its name to the arrangement of its brightest patches of nebulosity, that somewhat resemble the legs of a spider. They extend from a central 'body' where a cluster of hot stars (designated 'R136') illuminates and shapes the nebula. This name, of the biggest spiders on the Earth, is also very fitting in view of the gigantic proportions of the celestial nebula - it measures nearly 1,000 light-years across and extends over more than one third of a degree: almost, but not quite, the size of the full Moon. If it were in our own Galaxy, at the distance of another stellar nursery, the Orion Nebula (1,500 light-years away), it would cover one quarter of the sky and even be visible in daylight. One square degree image of the Tarantula Nebula and its surroundings. The spidery nebula is seen in the upper- center of the image. Slightly to the lower-right, a web of filaments harbors the famous supernova SN 1987A (see below). Many other reddish nebulae are visible in the image, as well as a cluster of young stars on the left, known as NGC 2100. Credit: ESO Known as the Tarantula Nebula for its spidery appearance, the 30 Doradus complex is a monstrous stellar factory. It is the largest emission nebula in the sky, and can be seen far down in the southern sky at a distance of about 170,000 light- years, in the southern constellation Dorado (The Swordfish or the Goldfish). -

Luminosity - Wikipedia

12/2/2018 Luminosity - Wikipedia Luminosity In astronomy, luminosity is the total amount of energy emitted by a star, galaxy, or other astronomical object per unit time.[1] It is related to the brightness, which is the luminosity of an object in a given spectral region.[1] In SI units luminosity is measured in joules per second or watts. Values for luminosity are often given in the terms of the luminosity of the Sun, L⊙. Luminosity can also be given in terms of magnitude: the absolute bolometric magnitude (Mbol) of an object is a logarithmic measure of its total energy emission rate. Contents Measuring luminosity Stellar luminosity Image of galaxy NGC 4945 showing Radio luminosity the huge luminosity of the central few star clusters, suggesting there is an Magnitude AGN located in the center of the Luminosity formulae galaxy. Magnitude formulae See also References Further reading External links Measuring luminosity In astronomy, luminosity is the amount of electromagnetic energy a body radiates per unit of time.[2] When not qualified, the term "luminosity" means bolometric luminosity, which is measured either in the SI units, watts, or in terms of solar luminosities (L☉). A bolometer is the instrument used to measure radiant energy over a wide band by absorption and measurement of heating. A star also radiates neutrinos, which carry off some energy (about 2% in the case of our Sun), contributing to the star's total luminosity.[3] The IAU has defined a nominal solar luminosity of 3.828 × 102 6 W to promote publication of consistent and comparable values in units of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luminosity 1/9 12/2/2018 Luminosity - Wikipedia the solar luminosity.[4] While bolometers do exist, they cannot be used to measure even the apparent brightness of a star because they are insufficiently sensitive across the electromagnetic spectrum and because most wavelengths do not reach the surface of the Earth. -

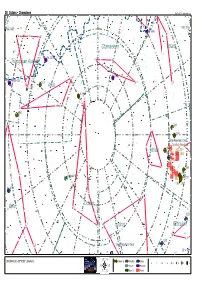

Skytools Chart

38 Octans - Chamaleon SkyTools 3 / Skyhound.com β NGC 6025 NGC 2516 IC 2448 β β ε γ Chamaeleon Volans δ ε ε PK 315-13.1 Triangulum Australe β γ 12h δ2 α ε 3195 ζ PK 325-12.1 1 α ζ 6101 5h η θ δ α Apus 09h 2 IC 4499 γ δ1 β γ ζ 6362 η 2 2210 η 2164 18h 06h Large Magellanic Cloud Tarantula Nebulaδ Mensa 2031 NGC 2014 NGC 1962 NGC 1955 ζ NGC 1874 NGC 1829 θ 1866 κ NGC 1770 1805 Collinder 411 NGC 1814 1978 1818 1783 03h 6744 21h β ε ε γ Octans Pavo ν -80° 00h ν 1559 β α δ θ Hydrus Reticulum β γ ι δ 1313 β Small Magellanic Cloud 0° 52° x 34° -7 ε ζ κ 00h00m00.0s -90°00'00" (Skymark) Globular Cl. Dark Neb. Galaxy 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Globule Planetary Open Cl. Nebula 38 Octans - Chamaleon GALASSIE Sigla Nome Cost. A.R. Dec. Mv. Dim. Tipo Distanza 200/4 80/11,5 20x60 NGC 292 Small Magellanic Cloud Tuc 00h 52m 38s +72° 48' 01” +2,80 318',0x204',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1313 Ret 03h 18m 15s -66° 29' 51” +9,70 9',5x7',2 Sbcd 13,5 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1559 Ret 04h 17m 36s -62° 47' 01" +11,00 4',2x2',1 SBc 34,0 Mly --- --- --- PGC 17223 Large Magellanic Cloud Dor 05h 23m 35s -69° 45' 22" +0,80 648',0x552',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 6744 Pav 19h 09m 46s -63° 51' 28" +9,10 17',0x10',7 SABb 21,0 Mly --- --- --- AMMASSI APERTI Sigla Nome Cost. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

A&A 496, 153–176 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:200811096 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics A census of molecular hydrogen outflows and their sources along the Orion A molecular ridge Characteristics and overall distribution C. J. Davis1, D. Froebrich2,T.Stanke3,S.T.Megeath4,M.S.N.Kumar5,A.Adamson1,J.Eislöffel6,R.Gredel7, T. Khanzadyan8,P.Lucas9,M.D.Smith2, and W. P. Varricatt1 1 Joint Astronomy Centre, 660 North A’ohok¯ u¯ Place, University Park, Hilo, Hawaii 96720, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 Centre for Astrophysics & Planetary Science, School of Physical Sciences, University of Kent, Canterbury CT2 7NR, UK 3 European Southern Observatory, Garching, Germany 4 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH 43606-3390, USA 5 Centro de Astrofisica da Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas s/n 4150-762 Porto, Portugal 6 Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg, Sternwarte 5, 07778 Tautenburg, Germany 7 Max Plank Institute für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 8 Centre for Astronomy, Department of Experimental Physics, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland 9 Centre for Astrophysics Research, Science & Technology Research Institute, University of Hertfordshire, College Lane, Hatfield AL10 9AB, UK Received 6 October 2008 / Accepted 16 December 2008 ABSTRACT Aims. A census of molecular hydrogen flows across the entire Orion A giant molecular cloud is sought. With this paper we aim to associate each flow with its progenitor and associated molecular core, so that the characteristics of the outflows and outflow sources can be established. Methods. We present wide-field near-infrared images of Orion A, obtained with the Wide Field Camera, WFCAM, on the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope. -

On the Effects of Subvirial Initial Conditions and the Birth

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 24 October 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) On the Effects of Subvirial Initial Conditions and the Birth Temperature of R136 Daniel P. Caputo1⋆, Nathan de Vries1 and Simon Portegies Zwart1 1Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands 24 October 2018 ABSTRACT We investigate the effect of different initial virial temperatures, Q, on the dynamics of star clusters. We find that the virial temperature has a strong effect on many aspects of the resulting system, including among others: the fraction of bodies escaping from the system, the depth of the collapse of the system, and the strength of the mass segregation. These differences deem the practice of using “cold” initial conditions no longer a simple choice of convenience. The choice of initial virial temperature must be carefully considered as its impact on the remainder of the simulation can be profound. We discuss the pitfalls and aim to describe the general behavior of the collapse and the resultant system as a function of the virial temperature so that a well reasoned choice of initial virial temperature can be made. We make a correction to the previous theoretical estimate for the minimum radius, Rmin, of the cluster at the deepest (−1/3) moment of collapse to include a Q dependency, Rmin ≈ Q+N , where N is the number of particles. We use our numericalresults to infer more aboutthe initial conditions of the young cluster R136. Based on our analysis, we find that R136 was likely formed with a rather cool, but not cold, initial virial temperature (Q ≈ 0.13). -

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and Astrophysical Phenomena Therein

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and astrophysical phenomena therein No. 135 — 1 June 2015 http://www.astro.keele.ac.uk/MCnews Editor: Jacco van Loon Editorial Dear Colleagues, It is my pleasure to present you the 135th issue of the Magellanic Clouds Newsletter. From magnetism and galactic structure and interaction, to variable, massive, (post-)AGB and exploding stars, and more on star cluster content – there’s something for everyone. Hope to see you at the IAU General Assembly in August, or in Baltimore in October! The next issue is planned to be distributed on the 1st of August. Editorially Yours, Jacco van Loon 1 Refereed Journal Papers Photometric identification of the periods of the first candidate extragalactic magnetic stars Ya¨el Naz´e1, Nolan R Walborn2, Nidia Morrell3, Gregg A Wade4 and MichaÃl K. Szyma´nski5 1University of LI`ege, Belgium 2STScI, USA 3Las Campanas Observatory, Chile 4Royal Military College, USA 5Warsaw University, Poland Galactic stars belonging to the Of?p category are all strongly magnetic objects exhibiting rotationally modulated spectral and photometric changes on timescales of weeks to years. Five candidate Of?p stars in the Magellanic Clouds have been discovered, notably in the context of ongoing surveys of their massive star populations. Here we describe an investigation of their photometric behaviour, revealing significant variability in all studied objects on timescales of one week to more than four years, including clearly periodic variations for three of them. Their spectral characteristics along with these photometric changes provide further support for the hypothesis that these are strongly magnetized O stars, analogous to the Of?p stars in the Galaxy. -

Astronomy Magazine Special Issue

γ ι ζ γ δ α κ β κ ε γ β ρ ε ζ υ α φ ψ ω χ α π χ φ γ ω ο ι δ κ α ξ υ λ τ μ β α σ θ ε β σ δ γ ψ λ ω σ η ν θ Aι must-have for all stargazers η δ μ NEW EDITION! ζ λ β ε η κ NGC 6664 NGC 6539 ε τ μ NGC 6712 α υ δ ζ M26 ν NGC 6649 ψ Struve 2325 ζ ξ ATLAS χ α NGC 6604 ξ ο ν ν SCUTUM M16 of the γ SERP β NGC 6605 γ V450 ξ η υ η NGC 6645 M17 φ θ M18 ζ ρ ρ1 π Barnard 92 ο χ σ M25 M24 STARS M23 ν β κ All-in-one introduction ALL NEW MAPS WITH: to the night sky 42,000 more stars (87,000 plotted down to magnitude 8.5) AND 150+ more deep-sky objects (more than 1,200 total) The Eagle Nebula (M16) combines a dark nebula and a star cluster. In 100+ this intense region of star formation, “pillars” form at the boundaries spectacular between hot and cold gas. You’ll find this object on Map 14, a celestial portion of which lies above. photos PLUS: How to observe star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies AS2-CV0610.indd 1 6/10/10 4:17 PM NEW EDITION! AtlAs Tour the night sky of the The staff of Astronomy magazine decided to This atlas presents produce its first star atlas in 2006. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

The Messenger

THE MESSENGER No, 40 - June 1985 Radial Veloeities of Stars in Globular Clusters: a Look into CD Cen and 47 Tue M. Mayor and G. Meylan, Geneva Observatory, Switzerland Subjected to dynamical investigations since the beginning photometry of several clusters reveals a cusp in the luminosity of the century, globular clusters still provide astrophysicists function of the central region, which could be the first evidence with theoretical and observational problems, wh ich so far have for collapsed cores. only been partly solved. The development of photoelectric cross-corelation tech If for a long time the star density projected on the sky was niques for the determination of stellar radial velocities opened fairly weil represented by simple dynamical models, recent the door to kinematical investigations (Gunn and Griffin, 1979, N .~- .", '. '.'., .' 1 '&307 w E ,. 1~ S Fig. 1: Left: 47 Tue (NGC 104) from the Deep Blue Survey - SRC-(J). Right: Centre of 47 Tue from a near-infrared photometrie study of Lioyd Evans. The diameter ofthe large eirele eorresponds to the disk ofthe left photograph. The maximum ofthe rotation appears inside the eircle; the linear part of the rotation eurve (solid-body rotation) affeets only stars inside one areminute of the eentre. 1 Rlre J 250r;.' .;r2' -i4.:...__.....;6;.;.. .;rB. ,;.;10::....--. Tentative Time-table of Council Sessions (J lkm/5] and Committee Meetings in 1985 (.) Gen x =2. November 12 Scientific Technical Committee November 13-14 Finance Committee December 11 -12 Observing Programmes Committee December 16 Committee of Council December 17 Council 10. All meetings will take place at ESO in Garching.