Dutch & Native American Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Newsletter

“Let’s talk it over at Mohonk Mohonk.” DECEMBER Consultations 2018 The beauty of the natural surroundings at Mohonk, along with its Quaker traditions of peaceful inclusiveness, provide a unique atmosphere for exchanging ideas and creating solutions. 2018 was a year of community building. Mohonk Consultations has helped communities face challenges and find solutions since our beginning in 1980. Our non-profit organization engages and convenes a diverse group of Hudson Valley residents to collaborate on regional issues with global significance. Our past conferences, forums, award ceremonies, and publications have focused on agriculture and food security, water resources, land conservation, social justice, peace building, and climate change. Mohonk Consultations’ mission has remained the same—to foster a clearer awareness of the interrelationship of all life on earth and help develop practical solutions. Throughout 2018, Mohonk Consultations kept its attention on building community, conservation, landscape connectivity, and sustainable agriculture in the Hudson Valley. We focused on pressing issues facing our local area while also incorporating national and global perspectives. Embraced by the inspiring venue of Mohonk Mountain House, our attendees shared their viewpoints, expertise, and experiences. As we look back, it’s worth recapping our final conference of 2017 that served as the foundation for our first 2018 event. On Monday, November 6, 2017 a sold-out conference, Nature Across Boundaries: Keeping Lands and Waters Connected was held in the Mohonk Mountain House Conference Center. Speakers and attendees came from throughout our region. Laura Heady, Mohonk Consultations board member and Conservation and Land Use Program Coordinator at the NYSDEC Hudson River Estuary Program kicked off the conference, putting “connectivity” into a Hudson Valley context. -

Journal of the Holland Society of New York Fall 2015 the Holland Society of New York

de Halve Maen Journal of The Holland Society of New York Fall 2015 The Holland Society of New York GIFT ITEMS for Sale www.hollandsociety.org “Beggars' Medal,” worn by William of Orange at the time of his assassination and adopted by The Holland Society of New York on March 30, 1887 as its official badge The medal is available in: Sterling Silver 14 Carat Gold $2,800.00 Please allow 6 weeks for delivery - image is actual size 100% Silk “Necktie” $85.00 “Self-tie Bowtie” $75.00 “Child's Pre-tied Bowtie” $45.00 “Lapel Pin” Designed to be worn as evidence of continuing pride in membership. The metal lapel pin depicts the Lion of Holland in red enamel upon a golden field. Extremely popular with members since 189 when adoped by the society. $45.00 Make checks payable to: The Holland Society of New York “Rosette” and mail to: 20 West 44th Street, Silk moiré lapel pin in orange, a New York, NY 10036 color long associated with the Dutch $25.00 Or visit our website and pay with Prices include shipping The Holland Society of New York 20 WEST 44TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10036 de Halve Maen President Magazine of the Dutch Colonial Period in America Robert R. Schenck Treasurer Secretary VOL. LXXXVIII Fall 2015 NUMBER 3 John G. Nevius R. Dean Vanderwarker III Domine IN THIS ISSUE: Rev. Paul D. Lent Advisory Council of Past Presidents 46 Editor’s Corner Roland H. Bogardus Kenneth L. Demarest Jr. Colin G. Lazier Rev. Louis O. Springsteen Peter Van Dyke W. -

Town of Wappinger Recommended Model Development Principles

Town of Wappinger Recommended Model Development Principles for Conservation of Natural Resources in the Hudson River Estuary Watershed Consensus of the Local Site Planning Roundtable A partnership among: Town of Wappinger, Dutchess County, New York Dutchess County Environmental Management Council Wappinger Creek Watershed Intermunicipal Council NYSDEC Hudson River Estuary Program Center for Watershed Protection, Maryland June 2006 Table of Contents Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary and Highlights ............................................................................................... 3 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 5 Membership Statement of Support .................................................................................................8 Recommended Model Development Principles.............................................................................. 9 Residential Streets, Parking and Lot Development............................................................... 9 Principle #1: Street Width....................................................................................................... 9 Principle #2: Street Length ................................................................................................... 10 Principle #3: Right-of-Way Width....................................................................................... -

Hudson Valley Community College

A.VII.4 Articulation Agreement: Hudson Valley Community College (HVCC) to College of Staten Island (CSI) Associate in Science in Business Administration (HVCC) to Bachelor of Science: International Business Concentration (CSI) THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ARTICULATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE AND COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND A. SENDING AND RECEIVING INSTITUTIONS Sending Institution: Hudson Valley Community College Department: Program: School of Business and Liberal Arts Business Administration Degree: Associate in Science (AS) Receiving Institution: College of Staten Island Department: Program: Lucille and Jay Chazanoff School of Business Business: International Business Concentration Degree: Bachelor of Science (BS) B. ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS FOR SENIOR COLLEGE PROGRAM Minimum GPA- 2.5 To gain admission to the College of Staten Island, students must be skill certified, meaning: • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in a credit-bearing mathematics course of at least 3 credits • Have earned a grade of 'C' or better in freshmen composition, its equivalent, or a higher-level English course Total transfer credits granted toward the baccalaureate degree: 63-64 credits Total additional credits required at the senior college to complete baccalaureate degree: 56-57 credits 1 C. COURSE-TO-COURSE EQUIVALENCIES AND TRANSFER CREDIT AWARDED HUDSON VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND Credits Course Number & Title Credits Course Number & Title Credits Awarded CORE RE9 UIREM EN TS: ACTG 110 Financial Accounting 4 -

Nimham Article Images Final

The Sherwood House in Yonkers is an example of what a typical tenant farmer house in the Hudson Valley might have looked like. (Image Credit: Yonkers Historical Society) Statue of Chief Nimham by local sculptor Michael Keropian. Michael based the likeness on careful research and correspondence with Nimham relatives. (Image Credit: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/Sachem_Daniel_Nimham.jpg/1200px- Sachem_Daniel_Nimham.Jpg) Memorial to Chief Nimham in Putnam County Veterans Park in Kent, NY. Sculpture by Michael Keropian. (Image Credit: Artist Michael Keropian) Recently issued Putnam County Veteran’s Medal by Sculptor Michael Keropian (Image Credit: Artist Michael Keropian) Sketch of Stockbridge Indians by Captain Johann Ewald. Ewald was in a Hessian Jager unit involved in the ambush of Nimham and his men in 1778. His sketch was accompanied by a vivid description of the Stockbridge fighters in his journal: “Their costume was a shirt of coarse linen down to the knees, long trousers also of linen down to the feet, on which they wore shoes of deerskin, and the head was covered with a hat made of bast. Their weapons were a rifle or a musket, a quiver with some twenty arrows, and a short battle-axe which they know how to throw very skillfully. Through the nose and in the ears they wore rings, and on their heads only the hair of the crown remained standing in a circle the size of a dollar-piece, the remainder being shaved off bare. They pull out with pincers all the hairs of the beard, as well as those on all other parts of the body.” (Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stockbridge_Militia) Portrait of Landlord Beverly Robinson, landlord of approximately 60,000 acres in Putnam County. -

Putnam Sheriff Releases Three Defendants Under Bail Law Cell

Reader-Supported News for Philipstown and Beacon Don Alter Show Page 9 JANUARY 10, 2020 Support us at highlandscurrent.org/join Cell Tower Settlement Draws Crowds Some Nelsonville residents urge board to fight on By Liz Schevtchuk Armstrong elsonville residents packed Village Hall twice this week to express N their dismay, frustration and, in some cases, support for a proposed settle- ment to lawsuits filed by telecommunica- tions firms after the village rejected plans for a cell tower on a ridge above the Cold Spring Cemetery. Lawyers for Nelsonville and the tele- com companies negotiated the settle- ment, which would allow a 95-foot tower disguised as a fir tree. The debate spread across Monday and CALL TO ARMS — Mame Diba led the Haldane boys' varsity basketball team with 19 points in a victory over league rival North Salem Wednesday nights (Jan. 6 and 8) as the on Jan. 4. The Blue Devils (6-2) will play Beacon on Jan. 17 in the first Battle of the Tunnel. For more, see Page 20. Photo by Amy Kubik mayor and four trustees heard feedback on an agreement that would end federal lawsuits filed by Homeland Towers and its partner, Verizon Wireless, and AT&T Beacon to Hold Forums on Development Mobility, which intends to use the Home- ning Board and Zoning Board of Appeals. City Administrator Anthony Ruggiero land-Verizon tower. Proposed by new mayor at The City Council, which also has two said he would come to the council’s next The companies sued in June 2018 after his first meeting new members — Air Rhodes and Dan workshop on Jan. -

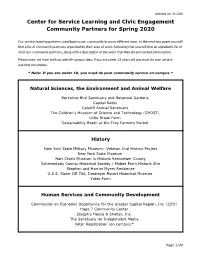

Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020

Updated Jan 16 2020 Center for Service Learning and Civic Engagement Community Partners for Spring 2020 Our service learning partners contribute to our community in many different ways. In the next two pages you will find a list of community partners organized by their area of work. Following that you will find an alphabetic list of all of our community partners, along with a description of the work that they do and contact information. Please note, we have both on and off-campus sites. If you are under 18 years old you must do your service learning on campus. * Note: If you are under 18, you must do your community service on-campus * Natural Sciences, the Environment and Animal Welfare Berkshire Bird Sanctuary and Botanical Gardens Capital Roots Catskill Animal Sanctuary The Children’s Museum of Science and Technology (CMOST) Little Brook Farm Sustainability Booth at the Troy Farmers Market History New York State Military Museum– Veteran Oral History Project New York State Museum Hart Cluett Museum in Historic Rensselaer County Schenectady County Historical Society / Mabee Farm Historic Site Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence U.S.S. Slater DE 766, Destroyer Escort Historical Museum Yates Farm Human Services and Community Development Commission on Economic Opportunity for the Greater Capital Region, Inc. (CEO) Hope 7 Community Center Joseph’s House & Shelter, Inc. The Sanctuary for Independent Media Voter Registration (on campus)* Page 1/20 Updated Jan 16 2020 Literacy and adult education English Conversation Partners Program (on campus)* Learning Assistance Center (on campus)* Literacy Volunteers of Rensselaer County The RED Bookshelf Daycare, school and after-school programs, children’s activities Albany Free School Albany Police Athletic League (PAL), Inc. -

The Erie Canal in Cohoes

SELF GUIDED TOUR THE ERIE CANAL IN COHOES Sites of the Enlarged Erie Canal Sites of the Original Erie Canal Lock 9 -In George Street Park, north oF Lock 17 -Near the intersection oF John Old Juncta - Junction of the Champlain Alexander Street. and Erie Sts. A Former locktender’s house, and Erie Canals. Near the intersection of Lock 10 -Western wall visible in George now a private residence, is located to the Main and Saratoga Sts. Street Park. A towpath extends through west of the lock. A well-preserved section the park to Lock 9 and Alexander Street. of canal prism is evident to the north of Visible section of “Clinton’s Ditch” southwest of the intersection of Vliet and Lock 11 -Northwest oF the intersection oF the lock. N. Mohawk Sts. Later served as a power George Street and St. Rita’s Place. Lock 18 -West oF North Mohawk Street, canal for Harmony Mill #2; now a park. Lock 12 -West oF Sandusky Street, north of the intersection of North Mohawk partially under Central Ave. Firehouse. and Church Sts. Individual listing on the Old Erie Route - Sections follow Main National Register of Historic Places. and N. Mohawk Streets. Some Lock 13 - Buried under Bedford Street, structures on Main Street date from the south of High Street. No longer visible. early canal era. Lock 14 - East of Standish Street, The Pick of the Locks connected by towpath to Lock 15. A selection of sites for shorter tours Preserving Cohoes Canals & Lock 15 - Southeast of the intersection of Locks Spindle City Historic Vliet and Summit Streets. -

Dutch Influences on Law and Governance in New York

DUTCH INFLUENCES 12/12/2018 10:05 AM ARTICLES DUTCH INFLUENCES ON LAW AND GOVERNANCE IN NEW YORK *Albert Rosenblatt When we talk about Dutch influences on New York we might begin with a threshold question: What brought the Dutch here and how did those beginnings transform a wilderness into the greatest commercial center in the world? It began with spices and beaver skins. This is not about what kind of seasoning goes into a great soup, or about European wearing apparel. But spices and beaver hats are a good starting point when we consider how and why settlers came to New York—or more accurately—New Netherland and New Amsterdam.1 They came, about four hundred years ago, and it was the Dutch who brought European culture here.2 I would like to spend some time on these origins and their influence upon us in law and culture. In the 17th century, several European powers, among them England, Spain, and the Netherlands, were competing for commercial markets, including the far-east.3 From New York’s perspective, the pivotal event was Henry Hudson’s voyage, when he sailed from Holland on the Halve Maen, and eventually encountered the river that now bears his name.4 Hudson did not plan to come here.5 He was hired by the Dutch * Hon. Albert Rosenblatt, former Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, is currently teaching at NYU School of Law. 1 See COREY SANDLER, HENRY HUDSON: DREAMS AND OBSESSION 18–19 (2007); ADRIAEN VAN DER DONCK, A DESCRIPTION OF NEW NETHERLAND 140 (Charles T. -

Upper Hudson Basin

UPPER HUDSON BASIN Description of the Basin The Upper Hudson Basin is the largest in New York State (NYS) in terms of size, covering all or part of 20 counties and about 7.5 million acres (11,700 square miles) from central Essex County in the northeastern part of the State, southwest to central Oneida County in north central NYS, southeast down the Hudson River corridor to the State’s eastern border, and finally terminating in Orange and Putnam Counties. The Basin includes four major hydrologic units: the Upper Hudson, the Mohawk Valley, the Lower Hudson, and the Housatonic. There are about 23,000 miles of mapped rivers and streams in this Basin (USGS Watershed Index). Major water bodies include Ashokan Reservoir, Esopus Creek, Rondout Creek, and Wallkill River (Ulster and Orange Counties) in the southern part of the Basin, Schoharie Creek (Montgomery, Greene, and Schoharie Counties) and the Mohawk River (from Oneida County to the Hudson River) in the central part of the Basin, and Great Sacandaga Lake (Fulton and Saratoga Counties), Saratoga Lake (Saratoga County), and Schroon Lake (Warren and Essex Counties) in the northern part of the Basin. This region also contains many smaller lakes, ponds, creeks, and streams encompassing thousands of acres of lentic and lotic habitat. And, of course, the landscape is dominated by one of the most culturally, economically, and ecologically important water bodies in the State of New York - the Hudson River. For hundreds of years the Hudson River has helped bolster New York State’s economy by sustaining a robust commercial fishery, by providing high value residential and commercial development, and by acting as a critical transportation link between upstate New York/New England and the ports of New York City. -

GUIDE to the SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS SCENIC BYWAY and REGION Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Access Map

GUIDE TO THE SHAWANGUNK MOUNTAINS SCENIC BYWAY AND REGION Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Access Map Shawangunk Mountain Scenic Byway Other State Scenic Byways G-2 How To Get Here Located in the southeast corner of the State, in southern Ulster and northern Orange counties, the Shawangunk Mountains Scenic Byway is within an easy 1-2 hour drive for people from the metro New York area or Albany, and well within a day’s drive for folks from Philadelphia, Boston or New Jersey. Access is provided via Interstate 84, 87 and 17 (future I86) with Thruway exits 16-18 all good points to enter. At I-87 Exit 16, Harriman, take Rt 17 (I 86) to Rt 302 and go north on the Byway. At Exit 17, Newburgh, you can either go Rt 208 north through Walden into Wallkill, or Rt 300 north directly to Rt 208 in Wallkill, and you’re on the Byway. At Exit 18, New Paltz, the Byway goes west on Rt. 299. At Exit 19, Kingston, go west on Rt 28, south on Rt 209, southeast on Rt 213 to (a) right on Lucas Turnpike, Rt 1, if going west or (b) continue east through High Falls. If you’re coming from the Catskills, you can take Rt 28 to Rt 209, then south on Rt 209 as above, or the Thruway to Exit 18. From Interstate 84, you can exit at 6 and take 17K to Rt 208 and north to Wallkill, or at Exit 5 and then up Rt 208. Or follow 17K across to Rt 302. -

Episodes from a Hudson River Town Peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’S 4,200-Foot Slide Mountain, May Have Poked up out of the Frozen Terrain

1 Prehistoric Times Our Landscape and First People The countryside along the Hudson River and throughout Greene County always has been a lure for settlers and speculators. Newcomers and longtime residents find the waterway, its tributaries, the Catskills, and our hills and valleys a primary reason for living and enjoying life here. New Baltimore and its surroundings were formed and massaged by the dynamic forces of nature, the result of ongoing geologic events over millions of years.1 The most prominent geographic features in the region came into being during what geologists called the Paleozoic era, nearly 550 million years ago. It was a time when continents collided and parted, causing upheavals that pushed vast land masses into hills and mountains and complementing lowlands. The Kalkberg, the spiny ridge running through New Baltimore, is named for one of the rock layers formed in ancient times. Immense seas covered much of New York and served as collect- ing pools for sediments that consolidated into today’s rock formations. The only animals around were simple forms of jellyfish, sponges, and arthropods with their characteristic jointed legs and exoskeletons, like grasshoppers and beetles. The next integral formation event happened 1.6 million years ago during the Pleistocene epoch when the Laurentide ice mass developed in Canada. This continental glacier grew unyieldingly, expanding south- ward and retreating several times, radically altering the landscape time and again as it traveled. Greene County was buried. Only the highest 5 © 2011 State University of New York Press, Albany 6 / Episodes from a Hudson River Town peak of the Catskills, Ulster County’s 4,200-foot Slide Mountain, may have poked up out of the frozen terrain.