The Red and the Black the Russian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raya Dunayevskaya Papers

THE RAYA DUNAYEVSKAYA COLLECTION Marxist-Humanism: Its Origins and Development in America 1941 - 1969 2 1/2 linear feet Accession Number 363 L.C. Number ________ The papers of Raya Dunayevskaya were placed in the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in J u l y of 1969 by Raya Dunayevskaya and were opened for research in May 1970. Raya Dunayevskaya has devoted her l i f e to the Marxist movement, and has devel- oped a revolutionary body of ideas: the theory of state-capitalism; and the continuity and dis-continuity of the Hegelian dialectic in Marx's global con- cept of philosophy and revolution. Born in Russia, she was Secretary to Leon Trotsky in exile in Mexico in 1937- 38, during the period of the Moscow Trials and the Dewey Commission of Inquiry into the charges made against Trotsky in those Trials. She broke politically with Trotsky in 1939, at the outset of World War II, in opposition to his defense of the Russian state, and began a comprehensive study of the i n i t i a l three Five-Year Plans, which led to her analysis that Russia is a state-capitalist society. She was co-founder of the political "State-Capitalist" Tendency within the Trotskyist movement in the 1940's, which was known as Johnson-Forest. Her translation into English of "Teaching of Economics in the Soviet Union" from Pod Znamenem Marxizma, together with her commentary, "A New Revision of Marxian Economics", appeared in the American Economic Review in 1944, and touched off an international debate among theoreticians. -

The Arts of Resistance in the Poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson1

Revista África e Africanidades - Ano 3 - n. 11, novembro, 2010 - ISSN 1983-2354 www.africaeafricanidades.com The arts of resistance in the poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson1 Jair Luiz França Junior2 Resumo: Este artigo analisa insubordinação e resistência manifestas na poesia pós-colonial contemporânea como forma de subverter os discursos dominantes no ocidente. Mais especificamente, a análise centra-se em estratégias textuais de resistência no trabalho do poeta britânico-jamaicano Linton Kwesi Johnson (também conhecido como LKJ). A qualidade sincretista na obra desse poeta relaciona-se com diáspora, hibridismo e crioulização como formas de re[escre]ver discursos hegemônicos com bases (neo)coloniais. Críticas pós- coloniais, em geral, irão enquadrar esta análise de estratégias de dominação e resistência, mas algumas discussões a partir do domínio de história, sociologia e estudos culturais também poderão entrar no debate. Neste sentido, há uma grande variedade de teorias e argumentos que lidam com as contradições e incongruências na questão das relações de poder interligada à dominação e resistência. Para uma visão geral do debate, este estudo compõe uma tarefa tríplice. Primeiramente, proponho-me a fazer um breve resumo autobiográfico do poeta e as preocupações sócio-políticas em sua obra. Em seguida, apresento algumas leituras críticas de seus poemas a fim de embasar teorias que lidam com estratégias de dominação e resistência no âmbito da literatura. Por fim, investigo como estratégias de resistência diaspórica e hibridismo cultural empregados na poesia de Linton Kwesi Johnson podem contribuir para o distanciamento das limitações de dicotomias e também subverter o poder hegemônico. Além disso, este debate está preocupado com a crescente importância de estudos acadêmicos voltado às literaturas pós-coloniais. -

The Arts of Resistance in the Poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson

THE ARTS OF RESISTANCE IN THE POETRY OF LINTON KWESI JOHNSON AS ARTES DA RESISTÊNCIA NA POESIA DE LINTON KWESI JOHNSON JLFrança Junior* Resumo Este artigo analisa insubordinação e resistência manifestas na poesia pós-colonial contemporânea como forma de subverter os discursos dominantes no ocidente. Mais especificamente, a análise centra-se em estratégias textuais de resistência no trabalho do poeta britânico-jamaicano Linton Kwesi Johnson. A qualidade sincretista em sua obra relaciona-se com diáspora, hibridismo e crioulização como formas de re[escre]ver discursos hegemônicos com bases (neo)coloniais. Críticas pós-coloniais, em geral, irão enquadrar esta análise. Este estudo está organizado em três debates fundamentais: um breve relato biográfico do autor e a contextualização sociopolítica em que sua obra se insere, alguns exames críticos da poesia de LKJ e um estudo das estratégias de resistência diaspórica e hibridismo cultural empregados na sua poesia. Este artigo visa, portanto, a fazer uma análise literária de poemas pós-coloniais como técnicas estratégicas de descentramento da retórica ocidental dominante, a qual tenta naturalizar desigualdades e injustiças em ambos os contextos local e global. Palavras-chave: Poesia Contemporânea, Crítica Pós-colonial, Diáspora, Crioulização, Resistência. Abstract This paper analyses insubordination and resistance manifested in contemporary postcolonial poetry as ways of subverting dominant Western discourses. More specifically, I focus my analysis on textual strategies of resistance in the works of the British-Jamaican poet Linton Kwesi Johnson. The syncretistic quality in his oeuvre is related to diaspora, hybridity and creolisation as forms of writ[h]ing against (neo)colonially-based hegemonic discourses. Thus postcolonial critiques at large will frame this analysis. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

Linton Kwesi Johnson: Poetry Down a Reggae Wire

LINTON KWESI JOHNSON: POETRY DOWN A REGGAE WIRE by Robert J. Stewart for "Poetry, Motion, and Praxis: Caribbean Writers" panel XVllth Annual Conference CARIBBEAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION St. George's, Grenada 26-29 May, 1992 LINTON KWESI JOHNSON: POETRY DOWN fl RE66flE WIRE Linton Kwesi Johnson had been writing seriously for about four years when his first published poem appeared in 1973. There had been nothing particularly propitious in his experience up to then to indicate that within a relatively short period of time he would become an internationally recognized writer and performer. Now, at thirty-nine years of age, he has published four books of poetry, has recorded seven collections of his poems set to music, and has appeared in public readings and performances of his work in at least twenty-one countries outside of England. He has also pursued a parallel career as a political activist and journalist. Johnson was born in Chapelton in the parish of Clarendon on the island of Jamaica in August 1952. His parents had moved down from the mountains to try for a financially better life in the town. They moved to Kingston when Johnson was about seven years old, leaving him with his grandmother at Sandy River, at the foot of the Bull Head Mountains. He was moved from Chapelton All-Age School to Staceyville All-Age, near Sandy River. His mother soon left Kingston for England, and in 1963, at the age of eleven, Linton emigrated to join her on Acre Lane in Brixton, South London.1 The images of black and white Britain immediately impressed young Johnson. -

The Volunteer the Volunteer

“...and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” ABRAHAM LINCOLN TheThe VVolunteerolunteer JOURNAL OF THE VETERANS OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN BRIGADE Vol. XXI, No. 4 Fall 1999 MONUMENTAL! Madison Dedicates Memorial ZITROM C to the Volunteers for Liberty ANIEL D By Daniel Czitrom PHOTOS Brilliant sunshine, balmy autumn weather, a magnificent setting Veteran Clarence Kailin at the Madison on Lake Mendota, an enthusiastic crowd of 300 people, and the Memorial dedication reminding spectators presence of nine Lincoln Brigade veterans from around the of the Lincolns’ ongoing commitment to social justice and the importance of pre- nation—all these helped turn the dedication of the nation's sec- serving historical memory. ond memorial to the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, in Madison, More photos page12 Wisconsin on October 31, into a joyful celebration. The two hour program combined elements of a political rally, family reunion, Continued on page 12 Letters to ALBA Sept 11th, 1999 who screwed up when there was still time for a peaceful Comrades, solution—negotiations moderated by Netherland arbiters. I cannot stomach the publication of that fucking I know there are some 60 vets, and maybe you as well, wishy-washy Office resolution on Kosovo, while [some] who will say, “But what about the people getting killed?” boast of the “democratic” vote that endorsed it. What the Good question. What about ‘em? They voted Slobodan in; hell was democratic about the procedure when only that they stood by him and his comrades re Croatia and Bosnia, resolution was put up for voting? No discussion, no they cheered him on in Kosovo . -

Raya Dunayevskaya's Intersectional Marxism Race, Class, Gender, and the Dialectics of Liberation

palgrave.com Political Science and International Relations : Political Theory Anderson, K.B., Durkin, K., Brown, H.A. (Eds.) Raya Dunayevskaya's Intersectional Marxism Race, Class, Gender, and the Dialectics of Liberation Presents the first edited collection on Dunayevskaya, a significant yet understudied figure in 20th century thought Covers the entirety of Dunayevskaya’s writings, thematically separated into four areas Features chapters from a diverse and global array of Humanist Marxists scholars Raya Dunayevskaya is one of the twentieth century’s great but underappreciated Marxist and Palgrave Macmillan feminist thinkers. Her unique philosophy and practice of Marxist-Humanism—as well as her 1st ed. 2021, XXI, 350 p. 1 grasp of Hegelian dialectics and the deep humanism that informs Marx’s thought—has much 1st illus. to teach us today. From her account of state capitalism (part of her socio-economic critique of edition Stalinism, fascism, and the welfare state), to her writings on Rosa Luxemburg, Black and women’s liberation, and labor, we are offered indispensable resources for navigating the perils of sexism, racism, capitalism, and authoritarianism. This collection of essays, from a diverse Printed book group of writers, brings to life Dunayevskaya’s important contributions. Revisiting her rich Hardcover legacy, the contributors to this volume engage with her resolute Marxist-Humanist focus and her penetrating dialectics of liberation that is connected to Black, labor, and women’s liberation Printed book and to struggles over alienation and exploitation the world over. Dunayevskaya’s Marxist- Hardcover Humanism is recovered for the twenty-first century and turned, as it was with Dunayevskaya ISBN 978-3-030-53716-6 herself, to face the multiple alienations and de-humanizations of social life. -

Nationality Issue in Proletkult Activities in Ukraine

GLOKALde April 2016, ISSN 2148-7278, Volume: 2 Number: 2, Article 4 GLOKALde is official e-journal of UDEEEWANA NATIONALITY ISSUE IN PROLETKULT ACTIVITIES IN UKRAINE Associate Professor Oksana O. GOMENIUK Ph.D. (Pedagogics), Pavlo TYchyna Uman State Pedagogical UniversitY, UKRAINE ABSTRACT The article highlights the social and political conditions under which the proletarian educational organizations of the 1920s functioned in the context of nationalitY issue, namelY the study of political frameworks determining the status of the Ukrainian language and culture in Ukraine. The nationalitY issue became crucial in Proletkult activities – a proletarian cultural, educational and literary organization in the structure of People's Commissariat, the aim of which was a broad and comprehensive development of the proletarian culture created by the working class. Unlike Russia, Proletkult’s organizations in Ukraine were not significantlY spread and ceased to exist due to the fact that the national language and culture were not taken into account and the contact with the peasants and indigenous people of non-proletarian origin was limited. KeYwords: Proletkult, worker, culture, language, policY, organization. FORMULATION OF THE PROBLEM IN GENERAL AND ITS CONNECTION WITH IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL TASKS ContemporarY social transformations require detailed, critical reinterpreting the experiences of previous generations. In his work “Lectures” Hegel wrote that experience and history taught that peoples and governments had never learnt from history and did not act in accordance with the lessons that historY could give. The objective study of Russian-Ukrainian relations require special attention that will help to clarify the reasons for misunderstandings in historical context, to consider them in establishing intercommunication and ensuring peace in the geopolitical space. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

Second Generation Return Migrants: the New Face of Brain Circulation in the Caribbean?

Second Generation Return Migrants: The New Face of Brain Circulation in the Caribbean? Claudette Russell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s of Arts in Globalization and International Development School of International Development and Global Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Claudette Russell, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 (ii) Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgement Acronyms List of figures and tables Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Research questions 1.2 How this research could be used 1.3 Structure of the thesis Chapter 2: Background/Context ..................................................................................... 7 2.1 Historical context 2.2 Current social, economic, and political context 2.3 Regional integration 2.4 Development opportunities and global positioning Chapter 3: Caribbean labour migration patterns ......................................................... 22 3.1 Migration and development 3.2 Push-pull factors – Explaining the migration process 3.3 Key migration patterns in the Caribbean 3.4 Brain drain effect Chapter 4: Methodology ................................................................................................ 36 Chapter 5: Literature review on return migration including SGRM to the Caribbean ... 44 5.1 Return migration 5.2 Circular migration and transnational movements 5.3 Review of literature on second generation return migration -

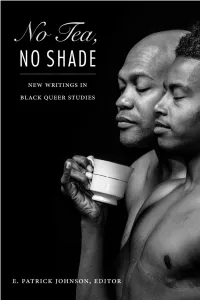

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M.