Tuomas Savonen Tuomas Savonen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PATTERSON, William

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 10-1-2015 PATTERSON, William MSRC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, MSRC, "PATTERSON, William" (2015). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 152. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/152 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCOPE NOTE The papers of William Lorenzo Patterson (1891-1980), often known as “Mr. Civil Rights,” document the life of the noted political activist, lawyer, orator, organizer, writer and Communist from San Francisco. The papers, which contain correspondence, printed materials, writings, and clippings, span the years 1919-1979. The bulk of the material covers the mid-1950s through 1979 when Patterson lived in New York. The collection measures approximately 15.5 linear feet and mostly highlights Patterson's political activism. His professional career as a lawyer can be analyzed through various cases he worked on through the Communist Party U.S.A. and the International Labor Defense. A view into his personal life can be obtained through his diaries and birthday tributes, as well as in the drafts and galleys of his autobiography, The Man Who Cried Genocide: An Autobiography. Correspondence with his third wife, Louise Thompson Patterson, their daughter, Mary Lou, and fellow activist leaders gives insight into some personal and political beliefs of Patterson, as do his writings on race relations, social injustices and the political activism of various individuals and organizations. -

Mccormick Foundation Civics Program Freedom of Speech: Clear & Present Danger

McCormick Foundation Civics Program 2010 First Amendment Summer Institute Freedom of Speech: Clear & Present Danger Shawn Healy Director of Educational Programs Civics Program Freedom of Speech o First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law…abridging…the freedom of speech…” o An historic progression of free speech tests: • Bad tendency -Rooted in English Common Law and articulated in Gitlow v. New York (1925) • Clear and present danger -First articulated by Holmes in Schenck v. U.S. (1919), and adopted by a majority of the Court in Herndon v. Lowry (1937) • Imminent lawless action -Supplants clear and present danger test in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) -Exception: speech cases in military courts Bad Tendency Test o World War I: Used as test to determine whether speech critical of government during the war and its aftermath crossed the line o Sedition Act of 1917: • Congress intended to forestall threats to military operations • The Wilson Administration used to prohibit dissenting views • Shaffer v. U.S. (9th Circuit Court of Appeals): “It is true that disapproval of war and the advocacy of peace are not crimes under the Espionage Act; but the question here is…whether the natural and probable tendency and effect of the words…are such as are calculated to produce the result condemned by the statute.” Bad Tendency Test Continued o Abrams v. U.S. (1919): • Pamphlet critical of Wilson’s decision to send troops to Russia, urging U.S. workers to strike in protest • Charged under 1918 amendment to Sedition Act prohibiting expression of disloyalty and interference with the war effort • Downplayed clear and present danger distinction: “for the language of these circulars was obviously intended to provoke and to encourage resistance to the United States and the war.” Bad Tendency Test Continued o Gitlow v. -

Dobbs on Truckers Strike Rebecca Finch, New York Socialist Workers Party Candi in New York City

FEBRUARY 22, 1974 25 CENTS VOLUME 38,1NUMBER 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE On-the-scene rel}orts Minnesota truckers vote Feb. 10 to continue strike. Reporters for the Militant aHended strike meetings around the country. For their reports, and special feature on Teamsters union and independent truckers in 1930s and today, see pages 5-9. riti m1ners• ae eat In Brief BERRIGAN REFUSED JOB AT ITHACA: 300 angry prisoners labeled "special offenders." students confronted Ithaca College President Henry Phillips Delegations from Rhode Island, Maine, and Connecti Feb. 7, demanding to know why the college withdrew an cut attended the rally, which was very spirited, despite offer of a visiting professorship to Father Daniel Berrigan. a heavy snowstorm. Speakers at the rally included Richard THIS The college made the offer last December and President Shapiro, executive director of the Prisoners Rights Project; Phillips withdrew it one month later without consulting Russell Carmichael of the New England Prisoners Associa students and faculty. tion; State Representative William Owens; and Jeanne Laf WEEK'S This was the second meeting called by students since ferty, Socialist Workers Party candidate for attorney gen a petition signed by 1,000 students failed to elicit a eral of Massachusetts. MILITANT response from the administration. The students are pro testing the arbitrary decision and demanding a full ex PUERTO RICAN POETRY FESTIVAL PLANNED: The 3 Union organizers speak planation for the withdrawal of the offer. Berrigan recently Committee for Puerto Rican Decolonization, an organiza out on fight of women criticized Israel's expansionist policies in the Mideast, which tion supporting the independence of Puerto Rico, is spon workers brought slanderous charges from pro-Zionist groups that soring a festival of Puerto Rican poetry. -

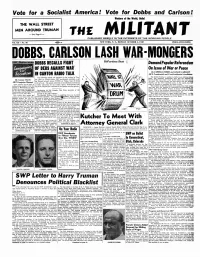

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

The Volunteer the Volunteer

“...and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” ABRAHAM LINCOLN TheThe VVolunteerolunteer JOURNAL OF THE VETERANS OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN BRIGADE Vol. XXI, No. 4 Fall 1999 MONUMENTAL! Madison Dedicates Memorial ZITROM C to the Volunteers for Liberty ANIEL D By Daniel Czitrom PHOTOS Brilliant sunshine, balmy autumn weather, a magnificent setting Veteran Clarence Kailin at the Madison on Lake Mendota, an enthusiastic crowd of 300 people, and the Memorial dedication reminding spectators presence of nine Lincoln Brigade veterans from around the of the Lincolns’ ongoing commitment to social justice and the importance of pre- nation—all these helped turn the dedication of the nation's sec- serving historical memory. ond memorial to the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, in Madison, More photos page12 Wisconsin on October 31, into a joyful celebration. The two hour program combined elements of a political rally, family reunion, Continued on page 12 Letters to ALBA Sept 11th, 1999 who screwed up when there was still time for a peaceful Comrades, solution—negotiations moderated by Netherland arbiters. I cannot stomach the publication of that fucking I know there are some 60 vets, and maybe you as well, wishy-washy Office resolution on Kosovo, while [some] who will say, “But what about the people getting killed?” boast of the “democratic” vote that endorsed it. What the Good question. What about ‘em? They voted Slobodan in; hell was democratic about the procedure when only that they stood by him and his comrades re Croatia and Bosnia, resolution was put up for voting? No discussion, no they cheered him on in Kosovo . -

October 14, 1976 I Yol.Xll, No

-v who liked our music a lot and some who new album (and other alternative didn't tike it at ¿ll) and after struggling a.lbums). Their letters tell incredible life with the question of oubeach vs. slories, sharing their eicitement, their compromise among ourselves, we fear, their discoveries, their risks. Being decided to do ourthird album on Red- a small company, they figured I might wood, once again. I am telieved that I'm gettheirletters. And I dol There is the not having to deal with the pressure of joy that must match the disappointment the industry but I'm sad when I think of in nof reaching all the women who don't all the people who don't have (oreven have access to an FM radio or altetnative October 14, 1976 I Yol.Xll, No. 34 know about) any optigns. So they watch concerts or womens' records etc. Alice Coopei whip a woman in one of his Right now Redwood Records is only on shocking displays recently performed on the distributing arm for the records and 4. Continental Walk Converges certainly bad news the Billboard Rock Music Awards. songbooks produced to date. We are not Washington / Crace Hedemann for the Portuguese Undet current conditions "energizing- working class, since it means, atbest, capital" can only be accomplishedby How are we going to get options to going to do any new things fot a while. and Murray Rosenblith But we hope that you will continue to the maintenance of the status quo. How- speedups, cutting real'rvages and people? Some people ate working within 6. -

Atio'nal Anti-Imperialist Conference Solidarity with African Liberation October 19,20,21,1973 at Du Bar Vocational High School 30Th and Dr

TO AFRO-AMERICANS OF EVERY STRATA: LABOR, CHU CH, POLITICAL, STUDE T, CULTURAL, CIVIC, AND COMMUNITY ATIO'NAL ANTI-IMPERIALIST CONFERENCE SOLIDARITY WITH AFRICAN LIBERATION OCTOBER 19,20,21,1973 AT DU BAR VOCATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 30TH AND DR. ARTIN LUTHER KING DRIVE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS PARTIAL LIST OF SPONSORS Rev. Ralph Abernathy - National President O'Dell Franklin - Secretary-Treasurer, SCLC ' Local #10 International Longshore and Rev. Forest Adams - Tucker Baptist Church Warehousemen's Union ~~'racuse, New York ' Hoyt Fuller - Editor, Black World Afro-American History and Cultural Society, Inc. Emily Gibson - Los Angeles Sentinel, Columnist Lerone Bennett - Senior Editor, Ebony Jesse Gray- New York State Assembly Black American Law Students Association man; National Tenants Organization Depauw University Chapter ' Dick Gregory-Chicago, Illinois Black.Women and Men - Los Angeles, CaHfornia Odela Griffin - Southern Committee to Free All Political Prisoners' Carl Bloice - Editor, Peoples World Irving Hamer - Urban League; Harlem Walter Boags - Kentucky Political Prison Street Academy ers Committee Edward Bragg - New York Black Trade Jack Hart-International Representative Unionists of the United Electrical, Radio and Professor Dennis Brutus - Northwestern Machine Workers of America University, Sec., Infl. C mpaign Against Professor Freddye Hill-Northwestern Racism In Sports, President, South University African Non-Racial Olympic Committee Esther Jackson - Managing Editor, Professor George Bunch - Afro-American Freedomways Studies, Syracuse, New York Hulbert James - President of the Board Haywood Burns- Executive Director, Pan-African Skills Program, New York National Conference of Black Lawyers Minerva Johnican - Democratic Coalition, Margaret Burroughs- Founder, DuSable Memphis, Tennessee Museum, Chicago, Illinois Professor Leon Johnson - Trenton State Father Robert Chapman - Former Director College of Social Justice, National Council of . -

Biographyelizabethbentley.Pdf

Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 1 of 284 QUEEN RED SPY Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 2 of 284 3 of 284 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet RED SPY QUEEN A Biography of ELIZABETH BENTLEY Kathryn S.Olmsted The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 4 of 284 © 2002 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet The University of North Carolina Press All rights reserved Set in Charter, Champion, and Justlefthand types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Olmsted, Kathryn S. Red spy queen : a biography of Elizabeth Bentley / by Kathryn S. Olmsted. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-8078-2739-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Bentley, Elizabeth. 2. Women communists—United States—Biography. 3. Communism—United States— 1917– 4. Intelligence service—Soviet Union. 5. Espionage—Soviet Union. 6. Informers—United States—Biography. I. Title. hx84.b384 o45 2002 327.1247073'092—dc21 2002002824 0605040302 54321 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 5 of 284 To 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet my mother, Joane, and the memory of my father, Alvin Olmsted Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 6 of 284 7 of 284 Contents Preface ix 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet Acknowledgments xiii Chapter 1. -

Women and the Presidency

Women and the Presidency By Cynthia Richie Terrell* I. Introduction As six women entered the field of Democratic presidential candidates in 2019, the political media rushed to declare 2020 a new “year of the woman.” In the Washington Post, one political commentator proclaimed that “2020 may be historic for women in more ways than one”1 given that four of these woman presidential candidates were already holding a U.S. Senate seat. A writer for Vox similarly hailed the “unprecedented range of solid women” seeking the nomination and urged Democrats to nominate one of them.2 Politico ran a piece definitively declaring that “2020 will be the year of the woman” and went on to suggest that the “Democratic primary landscape looks to be tilted to another woman presidential nominee.”3 The excited tone projected by the media carried an air of inevitability: after Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, despite receiving 2.8 million more popular votes than her opponent, ever more women were running for the presidency. There is a reason, however, why historical inevitably has not yet been realized. Although Americans have selected a president 58 times, a man has won every one of these contests. Before 2019, a major party’s presidential debates had never featured more than one woman. Progress toward gender balance in politics has moved at a glacial pace. In 1937, seventeen years after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Gallup conducted a poll in which Americans were asked whether they would support a woman for president “if she were qualified in every other respect?”4 * Cynthia Richie Terrell is the founder and executive director of RepresentWomen, an organization dedicated to advancing women’s representation and leadership in the United States. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Reviews / Comptes Rendus

Document generated on 09/29/2021 1:23 p.m. Labour/Le Travailleur Reviews / Comptes Rendus Volume 48, 2001 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/llt48rv01 See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Committee on Labour History ISSN 0700-3862 (print) 1911-4842 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article (2001). Reviews / Comptes Rendus. Labour/Le Travailleur, 48, 265–348. All rights reserved © Canadian Committee on Labour History, 2001 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ REVIEWS/COMPTES RENDUS Beverly Boutilier and Alison Prentice, religious and social convictions, and a eds. Creating Historical Memory: Eng study of the Ontario Women's Institutes' lish-Canadian Women and the Work of involvement in writing local histories. History, (Vancouver: UBC Press 1997) Despite differences, they shared a com mon interest in creating a history that BRINGING TOGETHER a collection of es would inspire Canadians to greater feel says highlighting the lives and works of ing for their country. women engaged in the writing and teach The second section, "Transitions," pro ing of history over the century spanning files historians who, through study and the 1870s to the 1970s, Beverly Boutilier adoption of professional historical re and Alison Prentice address the creation search methods, bridged the gap between of historical memory both inside and out "amateur" and "professional" history, side the academy.