Early Medieval Berkshire (AD410 – 1066)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Berkshire Echo 52

The Berkshire Echo Issue 52 l The Grand Tour: “gap” travel in the 18th century l Wartime harvest holidays l ‘A strange enchanted land’: fl ying to Paris, 1935 l New to the Archives From the Editor From the Editor It is at this time of year that my sole Holidays remain a status symbol Dates for Your Diary focus turns to my summer holidays. I in terms of destination and invest in a somewhat groundless belief accommodation. The modern Grand Heritage Open Day that time spent in a different location Tour involves long haul instead This year’s Heritage Open Day is Saturday will somehow set me up for the year of carriages, the lodging houses 11 September, and as in previous years, ahead. I am confi dent that this feeling and pensions replaced by fi ve-star the Record Offi ce will be running behind will continue to return every summer, exclusivity. Yet our holidays also remain the scenes tours between 11 a.m. and 1 and I intend to do nothing to prevent it a fascinating insight into how we choose p.m. Please ring 0118 9375132 or e-mail doing so. or chose to spend our precious leisure [email protected] to book a place. time. Whether you lie fl at out on the July and August are culturally embedded beach or make straight for cultural Broadmoor Revealed these days as the time when everyone centres says a lot about you. Senior Archivist Mark Stevens will be who can take a break, does so. But in giving a session on Victorian Broadmoor celebrating holidays inside this Echo, it So it is true for our ancestors. -

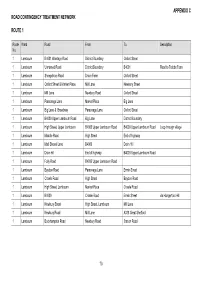

70 Appendix C Road Contingency Treatment

APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 1 Route Ward Road From To Description No. 1 Lambourn B4001 Wantage Road District Boundary Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Unnamed Road District Boundary B4001 Road to Trabbs Farm 1 Lambourn Sheepdrove Road Drove Farm Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Oxford Street & Market Place Mill Lane Newbury Street 1 Lambourn Mill Lane Newbury Road Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Parsonage Lane Market Place Big Lane 1 Lambourn Big Lane & Broadway Parsonage Lane Oxford Street 1 Lambourn B4000 Upper Lambourn Road Big Lane District Boundary 1 Lambourn High Street, Upper Lambourn B4000 Upper Lambourn Road B4000 Upper Lambourn Road Loop through village 1 Lambourn Maddle Road High Street End of highway 1 Lambourn Malt Shovel Lane B4000 Drain Hill 1 Lambourn Drain Hill End of highway B4000 Upper Lambourn Road 1 Lambourn Folly Road B4000 Upper Lambourn Road 1 Lambourn Baydon Road Parsonage Lane Ermin Street 1 Lambourn Crowle Road High Street Baydon Road 1 Lambourn High Street, Lambourn Market Place Crowle Road 1 Lambourn B4000 Crowle Road Ermin Street via Hungerford Hill 1 Lambourn Newbury Street High Street, Lambourn Mill Lane 1 Lambourn Newbury Road Mill Lane A338 Great Shefford 1 Lambourn Bockhampton Road Newbury Road Station Road 70 APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 1 (cont’d) Route Ward Road From To Description No. 1 Lambourn Edwards Hill Station Road High St, Lambourn 1 Lambourn Close End Edwards Hill End of highway 1 Lambourn Greenways Edwards Hill End of highway 1 Lambourn Baydon Road District Boundary A338 via Ermin Street 1 Lambourn Unnamed Road to Ramsbury Ermin Street District Boundary via Membury Industrial Estate 1 Lambourn B4001 B400 Ermin Street District Boundary 1 Lambourn, Newbury Road A338 Great Shefford Oxford Road via Boxford Kintbury & Speen 1 Kintbury High Street, Boxford Rood Hill B4000 Ermin Street 1 Speen Station Road A4 Grove Road 1 Speen Love Lane B4494 Oxford Road B4009 Long Lane 71 APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 2 Route Ward Road From To Description No. -

The Berkshire Echo 96

July 2021 l Abbey versus town l Hammer and chisel: Reading Abbey after the Dissolution l New to the Archives The Berkshire Echo WHAT’S ON From the Editor after a drawing by Paul Sandby (1731-1809) (D/EX2807/37/11) South ‘A Top: Prospect of the Abbey-Gate at Reading’, by Michael Angelo Rooker (c.1743-1801) Welcome to the Summer edition of the When the Abbey’s founder, Henry I, Where Smooth Waters Glide Berkshire Echo where we take a look died in Normandy in 1136, his body Take a look at our fantastic online into the history of Reading Abbey as was brought from there to be buried exhibition on the history of the River it celebrates its 900th anniversary in front of the high altar in the abbey Thames to mark 250 years of caring for this year. The abbey was founded in church. Unfortunately, as we discover the river at thames250exhibition.com June 1121 by Henry I and became one of in ‘Hammer and chisel’: Reading Abbey the richest and most important religious after the Dissolution, his coffin was institutions of medieval England. not handled very well later in the Pilgrims travelled to Reading to see nineteenth century. the hand of St James, a relic believed But how did it come to pass that the to have miraculous powers. The abbey resting place of a Royal was treated also has a place in the history of both this way? Well, it stems from another music and the English language, as royal – Henry VIII. After declaring it is believed to be the place where himself the Supreme Head of the the song ‘Summer is icumen in’ was Church of England in 1534, Henry VIII composed in the 13th century – the first disbanded monasteries across England, known song in English. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

The Berkshire Echo 44

The Berkshire Echo Issue 44 l 60 Years of BRO l County Archivist Hall of Fame l Choosing Favourites l From the Archives From the Editor From the Editor What made 1948 a special year? For Today we have over fi ve miles of shelving Dates for Your Diary some people doubtless it was the full of documents, between fi ve and six Heritage Open Day London Olympics, for others the thousand visitors annually, and several BRO will open its doors for tours founding of the National Health Service. thousand more enquiries by telephone, of both the public areas and But among the many events of that year, letter and e-mail. behind-the-scenes on 13 one, little noticed at the time, had a September, as part of the Heritage special signifi cance in the Royal County So this autumn we celebrate our sixtieth Open Days. If you would like of Berkshire, and that was the opening of birthday – sixty years of collecting to come along, please ask at the Berkshire Record Offi ce. and preserving records, sixty years of reception to book a place. welcoming visitors and encouraging That Berkshire needed a Record Offi ce research into the history of Berkshire Crime Festival had been recognised a decade earlier; and its people. Many thousands of Peter Bedford, Coroner for but war intervened, and it was not people have passed through our Berkshire, will be giving a talk until August 1948 that the fi rst County doors; many hundreds of books, in the Wroughton Room at BRO Archivist, Dr Felix Hull, was appointed. -

The Influence of Old Norse on the English Language

Antonius Gerardus Maria Poppelaars HUSBANDS, OUTLAWS AND KIDS: THE INFLUENCE OF OLD NORSE ON THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE HUSBANDS, OUTLAWS E KIDS: A INFLUÊNCIA DO NÓRDICO ANTIGO NA LÍNGUA INGLESA Antonius Gerardus Maria Poppelaars1 Abstract: What have common English words such as husbands, outlaws and kids and the sentence they are weak to do with Old Norse? Yet, all these examples are from Old Norse, the Norsemen’s language. However, the Norse influence on English is underestimated as the Norsemen are viewed as barbaric, violent pirates. Also, the Norman occupation of England and the Great Vowel Shift have obscured the Old Norse influence. These topics, plus the Viking Age, the Scandinavian presence in England, as well as the Old Norse linguistic influence on English and the supposed French influence of the Norman invasion will be described. The research for this etymological article was executed through a descriptive- qualitative approach. Concluded is that the Norsemen have intensively influenced English due to their military supremacy and their abilities to adaptation. Even the French-Norman French language has left marks on English. Nowadays, English is a lingua franca, leading to borrowings from English to many languages, which is often considered as invasive. But, English itself has borrowed from other languages, maintaining its proper character. Hence, it is hoped that this article may contribute to a greater acknowledgement of the Norse influence on English and undermine the scepticism towards the English language as every language has its importance. Keywords: Old Norse Loanwords, English Language, Viking Age, Etymology. Resumo: O que têm palavras inglesas comuns como husbands, outlaws e kids e a frase they are weak a ver com os Nórdicos? Todos esses exemplos são do nórdico antigo, a língua dos escandinavos. -

Newbury & Pangbourne

Autumn 2012 Newbury & Pangbourne 12_Newbury_and_Pangbourne_v2.indd 1 17/09/2012 13:51 &homes Newbury elcome to your property update for WNewbury & Pangbourne. We’re delighted to share with you some of the diverse properties that your local Strutt & Parker team has to o er, as well as our expert insight into your local In summer 2012, property market. For an innovative way to access Strutt & Parker saw a a large and enthusiastic pool of potential buyers, 64% or easily view a wide range of houses, contact us increase in instruction numbers and for details of Strutt & Parker’s upcoming Open 14.6 % House Day, taking place on Saturday 6 October. increase in exchange levels, compared with 2011. And from May 2011 to ‘There’s no doubt that June 2012, across the regions we produced there is an appetite’ on average The best phrase to sum up the As a national firm, Strutt & 2.75% current market in Newbury Parker attracts buyers from all IN EXCESS and Pangbourne is ‘tricky but over the UK and, increasingly, of our clients’ tradeable’. There is no doubt from overseas – not just expectations on price that there is an appetite to buy from London. We know our – as long as the property is marketplace, and target buyers well-presented and sensibly who we believe will be suitable priced – and over the past six for a property. In fact, we ‘The 12-month outlook for months we have agreed an recently agreed the private sale the UK property market impressive list of sales. of an attractive period property is muddled. -

Hatch Gate, Burghfield

Hatch Gate, Burghfield County: Berkshire Surveyor: James Moore Date: 2017-10-31 Branch: Reading & Mid-Berks GBG editions: Town/village: Burghfield Licensee: Marnie and Christopher Henke type: tie: District: Owner: Greene King Operator: Name: Hatch Gate LocalAuthority:West Berkshire Council (Burghfield & Mortimer) Listing: Protection: ACV: no Alt Name: Comment: Previous name: Real fire ✔ Station nearby 0 m ( ) Street: The Hatch Quiet pub Metro nearby m ( ) Postcode: RG30 3TH 0 Post Town: Underground nearby 0 m ( ) OS ref: Family friendly Bus stop nearby✔ 0 m ( 2, 143, 148, 149 ) Directions: Garden ✔ Camping nearby 0 m Opening times: 11.30-4.30, 5.30-11.30 Mon-Sat; Accommodation ✔ Real cider 12-4.30, 5.30-11.30 Sun Lunchtime meals ✔ WiFi✔ Meal times: 12-2, 6-9; 12-2.30, 6-9.30 Fri & Sat; Evening meals ✔ Car parking✔ 12-4 Sun Restaurant ✔ Function room Telephone: (0118) 983 2059 Separate bar ✔ Lined glasses Website: http://www.thehatchgateinn.co.uk/ ✔ Email: [email protected] Disabled access Uses misleading dispense Facebook: BurghfieldSpicesHatchGateInn Traditional games Uses cask breather Twitter: Smoking area Club allows CAMRA visitors Premises type: P comment Member discounts Historic interest: Premises status: O comment Live music✔ Fortnightly Sports TV✔ Open/close data: 0000-00-00 Newspapers Dog friendly LocAle Events Beer Fest Regular beers:Greene King IPA[H]; Greene King Abbot[H]; []; []; []; [] Typically from Number of changing real ales: 0 Description Two-roomed low-beamed pub, offering Indian food and Greene King beer, -

Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA EQUESTRIAN DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY at UPPER LAMBOURN Maddle Road, Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA

EQUESTRIAN DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Maddle Road, Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA EQUESTRIAN DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY AT UPPER LAMBOURN Maddle Road, Upper Lambourn, Berkshire RG17 8RA Lambourn 2 miles | Wantage 11 miles Marlborough 16 miles Newbury 17 miles | Oxford 27 miles (distances are approximate) A fantastic opportunity to purchase a greenfield site with planning consent for a new training yard in a prime location within the Valley of the Racehorse SITE ON MADDLE ROAD, UPPER SITUATION LAMBOURN The site is situated on the western fringe of the The Property for sale is a green field site with village of Upper Lambourn enjoying far reaching planning consent for a new training yard comprising views over the countryside whilst being only 8 miles a four-bedroom trainers house, 40 boxes, an eight- from the M4 Wickham Interchange. The location on bedroom hostel, storage barn, horse walker and a the edge of Upper Lambourn puts the property at office all set within approximately 2.45 acres (0.99 the heart of the racing community in the area and hectares). Once complete the Property will provide within easy reach of the Jockey Club Estates first superb training facilities in a prime location within class training grounds. the Valley of the Racehorse. The site is near to the village of Lambourn which Planning consent has been granted under provides a range of services including the Valley reference: 19/02596/FULD and permits the Equine Hospital, doctors surgery, a primary construction of the new equestrian training centre school along with various pubs, restaurants and in this prime location. The site affords excellent local shops. -

Lambourn Woodlands Church Plan

LAMBOURN WOODLANDS ST. MARY’S MARCH 2021 CHURCH PLAN Part A - Current Report Part B - Survey Results of our open survey conducted in Summer and Autumn 2020, canvassing all community contacts for their reaction to Part A. The survey remains open and available at this location. Please feel free to repeat your survey response or complete the survey for the first time. Part C - Community Recommendations Minutes of any community meetings held to discuss the information available in other parts of the Church Plan. Part D - Action Plan Details of any actions agreed through Community Recommendations, assigned to community participants, Churches Conservation Trust staff, or to the Churches Conservation Trust Local Community Officer specifically. Part A - Current Report Church Introduction & Statement of Significance St Mary's Church is a redundant Anglican church in the hamlet of Lambourn Woodlands in the English county of Berkshire. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II listed building, and is under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust. The church stands on the south side of the B4000 road, some 2 miles (3 km) south of Lambourn. The church was built in 1852 and designed by the architect Thomas Talbot Bury, a pupil of Augustus Charles Pugin, in Gothic Revival style. It was declared redundant on 1 June 1990, and was vested in the Churches Conservation Trust on 24 July 1991. St Mary's is constructed in flint with stone dressings, and has slate roofs. Its plan is simple, consisting of a three-bay nave, a north aisle and a chancel. -

West Berkshire

West Berkshire Personal Details: Name: Sarah Logan E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Comment text: Please can we stop wasting money on this sort of rubbish? Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded 10/6/2017 Local Government Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal West Berkshire Personal Details: Name: a markham E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Comment text: It is a good idea to have three councillor wards.The reason for this is that the constituents will have a cho ce as to wh ch councillor they contact. Furthermore it may well be the case that these members are of different political persuasions so mthe constituent again will have more cho ce. This is more democrat c abnd more efficient.. Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded https://consultation.lgbce.org.uk/node/print/informed-representation/10632 1/1 West Berkshire Personal Details: Name: Sarah Marshman E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Comment text: The Basildon and Compton Ward states it shall have 2 councillors. I would like to query why the ward should be made so large and then given two councillors - what is the benefit of this rather than making it two smaller wards with an individual councillor in each? It is a not-insignificant distance from the western to the eastern boundaries of this ward and it looks to me that the suggested ward could be split roughly in half, assigning one councillor to each ward. Uploaded Documents: None Uploaded West Berkshire Personal Details: Name: James Mathieson E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Comment text: This submission is in response to the most recent draft recommendations by LGBCE regarding the future composition of West Berkshire Council and the future geographic boundaries of individual wards. -

The Orchard Beenham

The Orchard • Beenham • Berkshire The Orchard • Beenham • Berkshire Theale train station 5 miles ● Newbury 9 miles ● Pangbourne 7 miles (all distances approximate) An individually designed 4 bedroom detached country house, set in this Sought-after, family orientated village. Walking distance to the village pub, hall and village green. 2,661 sq ft / 247 m² Gardens extending to 0.24 acre (all measurements are approximate) Your attention is drawn to the important notice on page 7 An outstanding, individually designed detached 4 bedroom country house, facing Quooker hot tap, polished quartz silestone worksurfaces. Walkthrough access to fields to both front and rear on the edge of this sought after, family orientated village. the garden room, utility room and dining room, with Karndean flooring which extends to the garden room The Orchard is in splendid order throughout, enjoying a large sunny plot on high ● Utility room has plumbing for washing machine and space for a tumble dryer ground, constructed approx. 25 years ago. This is a spacious, light family house with a ● Sitting room has a brick feature fireplace with old Bessamer beam fitted across, and galleried landing with window overlooking the front gardens and enjoying fine views, fitted with an oil-fired stove in the style of a wood burning stove over natural countryside. ● High ceilings with ancient exposed beams introduced in the sitting room, dining In excellent decorative order, having been updated to include replacement room, reception hall windows, the family bathroom and kitchen/breakfast room, and the principal bed- ● High level terrace dining areas to both front and rear room enjoying a dressing room with fitted wardrobes and a large ensuite shower ● Large excellent garden room overlooking the rear gardens, with French doors room.