Camera Focal Length and the Perception of Pictures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panoramas Shoot with the Camera Positioned Vertically As This Will Give the Photo Merging Software More Wriggle-Room in Merging the Images

P a n o r a m a s What is a Panorama? A panoramic photo covers a larger field of view than a “normal” photograph. In general if the aspect ratio is 2 to 1 or greater then it’s classified as a panoramic photo. This sample is about 3 times wider than tall, an aspect ratio of 3 to 1. What is a Panorama? A panorama is not limited to horizontal shots only. Vertical images are also an option. How is a Panorama Made? Panoramic photos are created by taking a series of overlapping photos and merging them together using software. Why Not Just Crop a Photo? • Making a panorama by cropping deletes a lot of data from the image. • That’s not a problem if you are just going to view it in a small format or at a low resolution. • However, if you want to print the image in a large format the loss of data will limit the size and quality that can be made. Get a Really Wide Angle Lens? • A wide-angle lens still may not be wide enough to capture the whole scene in a single shot. Sometime you just can’t get back far enough. • Photos taken with a wide-angle lens can exhibit undesirable lens distortion. • Lens cost, an auto focus 14mm f/2.8 lens can set you back $1,800 plus. What Lens to Use? • A standard lens works very well for taking panoramic photos. • You get minimal lens distortion, resulting in more realistic panoramic photos. • Choose a lens or focal length on a zoom lens of between 35mm and 80mm. -

Chapter 3 (Aberrations)

Chapter 3 Aberrations 3.1 Introduction In Chap. 2 we discussed the image-forming characteristics of optical systems, but we limited our consideration to an infinitesimal thread- like region about the optical axis called the paraxial region. In this chapter we will consider, in general terms, the behavior of lenses with finite apertures and fields of view. It has been pointed out that well- corrected optical systems behave nearly according to the rules of paraxial imagery given in Chap. 2. This is another way of stating that a lens without aberrations forms an image of the size and in the loca- tion given by the equations for the paraxial or first-order region. We shall measure the aberrations by the amount by which rays miss the paraxial image point. It can be seen that aberrations may be determined by calculating the location of the paraxial image of an object point and then tracing a large number of rays (by the exact trigonometrical ray-tracing equa- tions of Chap. 10) to determine the amounts by which the rays depart from the paraxial image point. Stated this baldly, the mathematical determination of the aberrations of a lens which covered any reason- able field at a real aperture would seem a formidable task, involving an almost infinite amount of labor. However, by classifying the various types of image faults and by understanding the behavior of each type, the work of determining the aberrations of a lens system can be sim- plified greatly, since only a few rays need be traced to evaluate each aberration; thus the problem assumes more manageable proportions. -

Ground-Based Photographic Monitoring

United States Department of Agriculture Ground-Based Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Photographic General Technical Report PNW-GTR-503 Monitoring May 2001 Frederick C. Hall Author Frederick C. Hall is senior plant ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Natural Resources, P.O. Box 3623, Portland, Oregon 97208-3623. Paper prepared in cooperation with the Pacific Northwest Region. Abstract Hall, Frederick C. 2001 Ground-based photographic monitoring. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-503. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 340 p. Land management professionals (foresters, wildlife biologists, range managers, and land managers such as ranchers and forest land owners) often have need to evaluate their management activities. Photographic monitoring is a fast, simple, and effective way to determine if changes made to an area have been successful. Ground-based photo monitoring means using photographs taken at a specific site to monitor conditions or change. It may be divided into two systems: (1) comparison photos, whereby a photograph is used to compare a known condition with field conditions to estimate some parameter of the field condition; and (2) repeat photo- graphs, whereby several pictures are taken of the same tract of ground over time to detect change. Comparison systems deal with fuel loading, herbage utilization, and public reaction to scenery. Repeat photography is discussed in relation to land- scape, remote, and site-specific systems. Critical attributes of repeat photography are (1) maps to find the sampling location and of the photo monitoring layout; (2) documentation of the monitoring system to include purpose, camera and film, w e a t h e r, season, sampling technique, and equipment; and (3) precise replication of photographs. -

AG-AF100 28Mm Wide Lens

Contents 1. What change when you use the different imager size camera? 1. What happens? 2. Focal Length 2. Iris (F Stop) 3. Flange Back Adjustment 2. Why Bokeh occurs? 1. F Stop 2. Circle of confusion diameter limit 3. Airy Disc 4. Bokeh by Diffraction 5. 1/3” lens Response (Example) 6. What does In/Out of Focus mean? 7. Depth of Field 8. How to use Bokeh to shoot impressive pictures. 9. Note for AF100 shooting 3. Crop Factor 1. How to use Crop Factor 2. Foal Length and Depth of Field by Imager Size 3. What is the benefit of large sensor? 4. Appendix 1. Size of Imagers 2. Color Separation Filter 3. Sensitivity Comparison 4. ASA Sensitivity 5. Depth of Field Comparison by Imager Size 6. F Stop to get the same Depth of Field 7. Back Focus and Flange Back (Flange Focal Distance) 8. Distance Error by Flange Back Error 9. View Angle Formula 10. Conceptual Schema – Relationship between Iris and Resolution 11. What’s the difference between Video Camera Lens and Still Camera Lens 12. Depth of Field Formula 1.What changes when you use the different imager size camera? 1. Focal Length changes 58mm + + It becomes 35mm Full Frame Standard Lens (CANON, NIKON, LEICA etc.) AG-AF100 28mm Wide Lens 2. Iris (F Stop) changes *distance to object:2m Depth of Field changes *Iris:F4 2m 0m F4 F2 X X <35mm Still Camera> 0.26m 0.2m 0.4m 0.26m 0.2m F4 <4/3 inch> X 0.9m X F2 0.6m 0.4m 0.26m 0.2m Depth of Field 3. -

Choosing Digital Camera Lenses Ron Patterson, Carbon County Ag/4-H Agent Stephen Sagers, Tooele County 4-H Agent

June 2012 4H/Photography/2012-04pr Choosing Digital Camera Lenses Ron Patterson, Carbon County Ag/4-H Agent Stephen Sagers, Tooele County 4-H Agent the picture, such as wide angle, normal angle and Lenses may be the most critical component of the telescopic view. camera. The lens on a camera is a series of precision-shaped pieces of glass that, when placed together, can manipulate light and change the appearance of an image. Some cameras have removable lenses (interchangeable lenses) while other cameras have permanent lenses (fixed lenses). Fixed-lens cameras are limited in their versatility, but are generally much less expensive than a camera body with several potentially expensive lenses. (The cost for interchangeable lenses can range from $1-200 for standard lenses to $10,000 or more for high quality, professional lenses.) In addition, fixed-lens cameras are typically smaller and easier to pack around on sightseeing or recreational trips. Those who wish to become involved in fine art, fashion, portrait, landscape, or wildlife photography, would be wise to become familiar with the various types of lenses serious photographers use. The following discussion is mostly about interchangeable-lens cameras. However, understanding the concepts will help in understanding fixed-lens cameras as well. Figures 1 & 2. Figure 1 shows this camera at its minimum Lens Terms focal length of 4.7mm, while Figure 2 shows the110mm maximum focal length. While the discussion on lenses can become quite technical there are some terms that need to be Focal length refers to the distance from the optical understood to grasp basic optical concepts—focal center of the lens to the image sensor. -

Digital Photography Basics for Beginners

DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY BASICS FOR BEGINNERS by Robert Berdan [email protected] www.canadiannaturephotographer.com These notes are free to use by anyone learning or teaching photography. 1. Choosing a camera - there are 2 main types of compact cameras A) Point and Shoot Camera (some have interchangeable lenses most don't) - you view the scene on a liquid crystal display (LCD) screen, some cameras also offer viewfinders. B) Single Lens Reflex (SLR) - cameras with interchangeable lenses let you see the image through the lens that is attached to the camera. What you see is what you get - this feature is particularly valuable when you want to use different types of lenses. Digital SLR Camera with Interchangeable zoom lens 1 Point and shoot cameras are small, light weight and can be carried in a pocket. These cameras tend to be cheaper then SLR cameras. Many of these cameras offer a built in macro mode allowing extreme close-up pictures. Generally the quality of the images on compact cameras is not as good as that from SLR cameras, but they are capable of taking professional quality images. SLR cameras are bigger and usually more expensive. SLRs can be used with a wide variety of interchangeable lenses such as telephoto lenses and macro lenses. SLR cameras offer excellent image quality, lots of features and accessories (some might argue too many features). SLR cameras also shoot a higher frame rates then compact cameras making them better for action photography. Their disadvantages include: higher cost, larger size and weight. They are called Single Lens Reflex, because you see through the lens attached to the camera, the light is reflected by a mirror through a prism and then the viewfinder. -

A Theoretical and Practical Introduction to Optics a Theoretical and Practical Introduction to Optics

White Paper A Theoretical and Practical Introduction to Optics A Theoretical and Practical Introduction to Optics Be honest: do you really know how to calculate the focal length of a lens? If so, you are an exception to the rule and can stop reading here !! For the rest of you, here is a second chance. Back to square one "Piece of broken glass starts forest fire"– a common headline during the summer. But how could this have happened? Due to the enormous distance between the Earth and the Sun, the Sun only appears as a tiny point emitting parallel rays of light (figure 1a) Should these parallel rays pass through a lens (or a piece of glass, which has similar characteristics) the rays would meet behind the lens at what is called the focal point. But what happens if our point of light is so near to the lens that we can not assume to have parallel rays of light? They cross each other behind the focal point (figure 1b). If we take a look at the image of our point of light at the focal points position we will see a unclear blurred spot. And so the question arises- "what is focusing?". Focusing is to increase the distance between the focal plane and the lens until the focal plane and the junction of the rays overlap each other (figure 1c). Thus, for single points of light the situation is quite simple. But what happens to the image of screws, PCBs or plates of steel? From points of light to images A point of light does not necessarily originate directly from the sun, candles or lamps, it can also result from a reflection. -

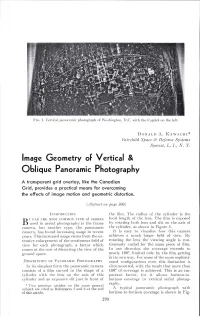

Image Geometry of Vertical & Oblique Panoramic Photography

FIG. 1. Vertical panoramic photograph of Washington, D.C. with the Capitol on the left. DONALD A. KAWACHI* Fairchild Space & Defense Systems Syosset, L. I., N. Y. Image Geometry of Vertical & Oblique Panoramic Photography A transparent grid overlay, like the Canadian Grid, provides a practical means for overcoming the effects of image motion and geometric distortion. (Abstract on page 300) INTRODUCTION the fil m. The radius of the cylinder is the y FAR THE MOST COMMON TYPE of camera focal length of the lens. The fil m is exposed B used in aerial photography is the frame by rotating both lens and slit on the axis of camera, but another type, the panoramic the cylinder, as shown in Figure 3. camera, has found increasing usage in recent I t is easy to visualize how this camera years. This increased usage stems from the ex achieves a much larger field of view. By tensive enlargement of the continuous field of rotating the lens the viewing angle is con view for each photograph, a factor which tinuously varied for the same piece of film. comes at the cost of distorting the view of the In one direction the coverage extends to ground space. nearly 180°, limited only by the film getting in its own way. For some of the more sophisti DESCRIPTION OF PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY cated configurations even this limitation is In its simplest form the panoramic camera circumvented, with the result that more than consists of a film curved in the shape of a 180° of coverage is achieved. This is an im cylinder with the lens on the axis of this portant factor, for it allows horizon-to cylinder and an exposure slit just in front of horizon coverage in vertical aerial photog raphy. -

The F-Word in Optics

The F-word in Optics F-number, was first found for fixing photographic exposure. But F/number is a far more flexible phenomenon for finding facts about optics. Douglas Goodman finds fertile field for fixes for frequent confusion for F/#. The F-word of optics is the F-number,* also known as F/number, F/#, etc. The F- number is not a natural physical quantity, it is not defined and used consistently, and it is often used in ways that are both wrong and confusing. Moreover, there is no need to use the F-number, since what it purports to describe can be specified rigorously and unambiguously with direction cosines. The F-number is usually defined as follows: focal length F-number= [1] entrance pupil diameter A further identification is usually made with ray angle. Referring to Figure 1, a ray from an object at infinity that is parallel to the axis in object space intersects the front principal plane at height Y and presumably leaves the rear principal plane at the same height. If f is the rear focal length, then the angle of the ray in image space θ′' is given by y tan θ'= [2] f In this equation, as in the others here, a sign convention for angles heights and magnifications is not rigorously enforced. Combining these equations gives: 1 F−= number [3] 2tanθ ' For an object not at infinity, by analogy, the F-number is often taken to be the half of the inverse of the tangent of the marginal ray angle. However, Eq. 2 is wrong. -

Control of Chromatic Focal Shift Through Wavefront Coding Hans B. Wach, W

Control of chromatic focal shift through wavefront coding Hans B. Wach, W. Thomas Cathey and Edward R. Dowski, Jr. Abstract Control of chromatic aberration through purely optical means is well known. We present a novel optical/digital method of controlling chromatic aberration. The optical/digital system, which incorporates a cubic phase modulation (CPM) plate in the optical system and post processing of the detected image, effectively reduces a system's sensitivity to misfocus in general or axial (longitudinal) chromatic aberration in particular. A fully achromatic imaging system ( one which is corrected for a continuous range of wavelengths ) can be achieved by initially correcting the optical system for lateral chromatic aberration through conventional techniques. Then the axial chromatic aberration is corrected by the inclusion of the CPM plate and post processing. 1. Introduction In general, optical system design consists of meeting specific requirements under some set of constraints. The constraints of a system vary from application to application. Cost, weight, size, number of optical elements, and materials comprising the optical elements are some typical constraints. Similarly, the performance requirements of a system are application dependent and often times include the minimization of aberrations. Some aberrations may or may not be important or they may be organized into a spectrum of tolerable to intolerable aberrations. Because meeting the system constraints can cause the aberrations to worsen and, conversely, minimizing the aberrations may require breaking the constraints, the challenge lies in making the tradeoff between the two. For example, the design of a digital color imaging system which uses only plastic optical elements is a nontrivial task. -

TECHSPEC® Fixed Focal Length Lenses

Edmund Optics® BROCHURE FIXED FOCAL LENGTH LENSES ® COPYRIGHT 2017 EDMUND OPTICS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 7/17 RIGHTS RESERVED ALL 2017 EDMUND OPTICS, INC. ® COPYRIGHT INNOVATION STARTS HERE . Global Design & Support | Rapid Prototyping Volume Manufacturing & Pricing Contact us for a Stock or Custom Quote Today! USA: +1-856-547-3488 | EUROPE: +44 (0) 1904 788600 ASIA: +65 6273 6644 | JAPAN: +81-3-3944-6210 www.edmundoptics.com/fixed-focal UC SERIES FIXED FOCAL LENGTH LENSES • Ultra-Compact (UC) Form Factor • 4K Resolution Designed for Small Pixels (≤2.2µm) • Optimized for 1/2•5" Sensors and Supports up to 1/1•8" Our ultra-compact, TECHSPEC® UC Series Fixed Focal Length Lenses are designed to optimize performance, cost, and size without sacrificing quality or feel. Designed for pixels that are ≤2.2μm, these lenses provide high levels of resolution (>200 lp/mm) across the sensor and are compatible with all standard C-Mount cameras. TECHSPEC® UC Series Fixed Focal Length Lenses feature focus and iris adjustments, as well as re- cessed set screws, and are manufactured for use at typical machine vision working distances. While they are optimized for 1/2.5" sensors, many focal lengths will work on sensors up to 1/1.8". The TECHSPEC® UC Series lenses are an outstanding option for use on all smaller format camera sensors, along with both short and long working dis- tance applications, making them ideal for inspection, factory automation, biomedical devices, and a broad range of other applications. Dimensions Units: mm Focal Length A B C D Filter Thread Focus Adjustment Iris Locking Screw Iris Adjustment Focus Locking Screw C-Mount 4mm 40 40.6 30 2.8 M62.0 x 0.75 with required filter adapter #33-308 6mm 36 40.9 30 3.2 M34.0 x 0.5 Max. -

Evolution Change the Concept of Focal Length?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography AARGnews 34 (March 2007) Did the digital (r)evolution change the concept of focal length? Geert Verhoeven Introduction The advent of digital photography opened a completely new world for a lot of people. Just look around: there has never been a moment in photography’s long history that so many people actually had and used a photo camera. However, along with new technology always come misconceptions. One of these often heard and read delusions is the fact that “the focal length of lenses changes when used on a digital camera”, leading to strongly magnified images as indicated by a so-called digital magnification factor . The purpose of this article is to prove the above statement (and term digital magnification factor) to be incorrect by outlining the concepts of focal length and image sensor size as well as their combined effect on field of view. Size matters * Film formats Although aerial photographers use(d) a variety of photographic film formats, this article will compare the 135 format to its digital equivalent, in order not to end up comparing apples to oranges. Launched in 1934, this format had the highest sales worldwide. Hence, a lot of people are not even aware of the fact that smaller as well as larger film formats exist. On one end of the range, one finds smaller film formats as the 110 or sub-miniature format (introduced by Kodak in 1972 and 16 mm wide) as well as the rather recently (1996) launched APS (Advanced Photo System ) format, characterized by a 24 mm wide film.